CURATOR OF ANTHROPOLOGY, DARTMOUTH MUSEUM

CENTURIES AGO, when Europe was fall- ing prey to the mass hysteria of the Crusades, and when the great em- pire of the Maya was dying in Middle America, a tiny band of fur-clad people coasted southward along the forbidding shores of Labrador and crossed at last to Newfoundland. They did not come in force, because the life of a primitive hunt- ing Eskimo was a harsh one, and there was never enough food easily available to support many tribesmen. For a few sea- sons, perhaps for many years, they lived near the Strait of Belle Isle, following their traditional ways of life, hunting the seals which clustered upon the rocky head- lands in the spring, and probably warring with the Indians who possessed the land before them. Then, while time swept on- ward for the rest of the world, it came to a halt for them. They disappeared. Today, we have little more than a name for these people, the Cape Dorset Eskimo.

I I ' X The million-year story of man is full of such incidents: many of them we shall never know, and the significance of others we may never be able to appreciate, for the clues are scant and dimmed by time. The archeologist, however, seeks for what- ever vestiges of pre-historic culture he can find, and tries to reconstruct from them the ways of man's life in the unrecorded past. More often than not this task is im- possible of complete fulfillment, but as a job of detection some of us think it ranks with tales of Holmes and Scotland Yard for fascination.

The techniques of scientific excavation are designed to retrieve the utmost resi- due of information from the ground, al- though at best the archeologist can never find more than the imperishable objects of the past. For example, today's town dump may yield up to the archeologist of the future certain cultural objects such as broken crankshafts, fragments of pots and pans, bed springs, old building bricks and pipe, and maybe rubber tires: these and many other steadfast things that have been preserved in burial are not, of course, rep- resentative of more than a small portion of our culture. Nevertheless, the trained archeologist, with careful regard for those universals of man's culture which we so far recognize, can make amazingly accu- rate inferences on the basis of such ma- terial discoveries. Also, as one approaches the primitive level, "where the life of a society becomes a simple day-to-day strug- gle for existence against the limiting fac- tors of the environment, these deductions may come close to the totality of life, as it was once known by early men.

The Cape Dorset people were the earli- est known prehistoric Eskimo in the north- eastern regions of this continent. They are so named because their cultural remains, first isolated and described 25 years ago by Dr. Diamond Jenness of the National Museum of Canada, came from a site at Cape Dorset on Baffin Island. As yet we know very little of these people, but we believe they can be traced ultimately to the earliest Eskimo migrants who moved out of Asia and entered the New World about 2000 years ago. For the past two summers I have travelled the coasts of Newfoundland and southern Labrador in search of their story. This research has been supported by the Arctic Institute of North America, and is but one aspect of our quest for knowledge of northern re- gions and their potentialities for mankind. In 1949 Stearns Morse, Dartmouth '52, acted as my field assistant, and during the past summer I was accompanied by my wife and our elder boy. We all survived the rigors of camping in the interior bush country and along the fog-swept coasts, the occasional bitter swarms of mosquitoes and black flies, and the frequently water- soaked travel in the small motor boats of local fishermen. There were many pleas- urable moments, too.

On Newfoundland's west coast, some forty miles south of the entrance to the Strait of Belle Isle, the barren rocks of Cape Rich jut seaward, and here our search uncovered heavy concentrations of the extinct Cape Dorset Eskimo culture. Within a three-mile stretch of the deeply indented coastline, six different occupation sites of these people were located. The most productive site of all, designated Port au Choix-2, was found far out on the northern shore where no one has lived since the Eskimo themselves encamped on the boulder-strewn beaches. So abundant are the buried remains in this place that a shovel can be stuck into the ground almost anywhere within an area of three acres and a find of chipped stone tools will result.

As in any other archeological excavation, we inescapably destroyed evidence as we dug through the site, and we had to take extreme care to preserve all data whether or not they appeared to be of any immediate significance. The prime necessity was to make a record so complete in words, measured drawings, and photographs, that any section of the dig might be reconstructed later on the basis of these notes. It is not only the artifacts themselves which count, but also their relationships, both spatial and temporal, with one another and their environment.

Approaching Port au Choix-2, we traversed a series of shelving limestone outcrops, and almost any path we chose to follow led ultimately to a grassy clearing which fronted on the sea and was otherwise surrounded by a ring of scrub firs. These stunted trees grew massed in thickets, crouched low against the northern winter winds. A profusion of wild iris carpeted the floor of the meadow, and a slope rose back from the gravelled landwash across two higher terraces which paralleled the present beach. The foreground of the meadow formed part of a shallow cove, and two points of rock projected at either end of this crescent. The local fishermen say these shingled points are still a favorite ground of the seal hunters from Flowers Cove? forty miles to the north. During the spring, when the herds are migrating northward into arctic waters, their progress is often stopped by ice fields choking off the Strait of Belle Isle. Then, if strong westerlies spring out of the Gulf of St. Lawrence, the herds congregate off the headland and become an easily taken prize.

A preliminary examination of the site showed up the presence of a few scrap chips of flint, and a quick scalping back of the turf further expanded this glimpse of buried culture. More chips occurred, everywhere, along with fine triangular arrow oints of flint, and scrapers, and bones. By means of a series of small test pits we blocked out the extent of the site, and also learned the nature of the soil profile. A densely packed stratum of black earth, from four to six inches thick, lay directly on top of a former beach of sand and gravel. This black earth, beneath its covering sod, was the culture zone. A rough map of the site was then sketched into the notebook, and the major dimensions paced off in order to obtain an approximate scale. With only a limited amount of time available, our work in this site was largely of a reconnaissance nature; the refinements of a topographic map and more intensive excavation would have to wait for another year.

As we tramped back and forth across the site, a new feature gradually began to appear. Obscured at first by the thickness of the wild iris, but then becoming more apparent in shadow patterns laid out by the slanting sun, a series of shallow pits took form. These were round and somewhat uniform in size, with diameters ranging between 10 and 15 feet. The overall distribution of the pits was haphazard, yet they appeared to be strung out longitudinally along the two terraces. There were 16 pits in all, and they did not seem to have any connection with white man and his colonization of the island, for, at least up to this point, no sign of European culture had been detected. Nevertheless, the structural regularities of this feature unmistakably denoted the hand of man. The next supposition was that they might be aboriginal house pits, but whatever the hypothesis, excavation would be the final test.

A good place to start digging seemed to be on the lower terrace which stood 15 feet above sea-level and 60 yards back from the landwash. Here, at the western end of the site, two pits ranked side by side. They were numbered 3 and 4 on our sketch map. In pit No. 3 two trenches were cut so as to form a right-angle cross in the center of the hollow. As soon as the turf was skinned back, chips of flint began to appear, and, as the black earth was trowelled away in patches, more finds of arrow points, scrapers, and stone knives were made. At the front of the pit, in the entrance gap, many fragments of charcoal occurred in the soil, and bits of burned, calcined bone. This appeared to be a section of hearth area, and strengthened the belief that these depressions were house pits.

The trenches within the pit were trowelled deeper until the soil layer had been removed; beneath was the sterile surface of the old beach. The next step was to check the ridges surrounding the pit, to see if there was any purposeful wall construction of stone, but none was found. The cuts through the ridges did, however, reveal portions of a ring of stones which appeared to have been piled around the exterior edges of a dwelling, possibly to anchor it to the ground. It seemed, then, that the ridges were something akin to tepee rings, and that the aborigines who once dwelt here probably lived in skin tents, all other traces of which had long since disappeared.

Now that we had some reasonably good data on the house pits, the next thing to do was expand operations by cutting a trench along the brow of the terrace, directly in front of dwellings No. 3 and No. 4. This yielded several hundred artifacts of stone and bone, each of which, accord- ing to customary procedure, was assigned a number and listed in the field catalog with brief notes of description and loca- tion.

The most striking aspect of the collec- tion is the general smallness of these spec- imens. A majority of them are made of black flint, and they have been chipped into their individual shapes with a master- ful pressure technique. There are trian- gular arrow p,oints with concave bases, snub-nosed skin scrapers, side-notched knife blades made on the most delicate of stone flakes. In addition to the chipped implements and their many variant forms, there are other knife blades and projectile points of polished stone with bevelled edges that have a sharp, almost mechani- cal, perfection. A few of the specimens are made of bone. Among these are long, stemmed lance points, and barbed har- poon heads with rectangular shaft sockets and line holes; also hafts, or handles, made for use with stone cutting tools, fragments of bone needles, one with an eye in its head, and sections of bone sled runner with striations on the undersides which indicate hard usage. The holes in these implements of bone are noteworthy in that they have all been gouged out. Ap- parently these people had no knowledge of the rotary drill which was one of the most important tools of later Eskimo crroups. Nor did the Cape Dorset folk have any earthenware pottery: all their cooking vessels and blubber lamps were carved from solid chunks of soapstone. We found many fragments, all of them from rectangular pots with nicely smoothed sides and well-turned corner angles. The bottoms of some were still deeply en- crusted with carbon from the camp fires of long ago.

The long trench on the lower terrace proved beyond doubt that the circular de- pressions sprinkled throughout the site were actually Cape Dorset Eskimo house pits. Directly in front of three of these dwellings hearth areas were found. Here the soil was heavily loaded with charcoal fragments, and quantities of ash inter- mixed with pieces of fire-scarred rock and splinters of calcined bone. On either side of the hearths, the trench exposed sections of extensive middens where there was an almost solid stratum of closely packed food bone. These were in an excellent state of preservation, and large samples were taken for later identification so that we may obtain a good idea of the food habits of these people. Immediately no- ticeable, however, was the abundance of seal remains, and in one spot we came across a buried pile of six seal skulls, testimony that the Eskimo too were in- terested in the spring migrations of the herds. Other bones that could be readily identified in the field were those of cari- bou, fox, birds, fish, and lobster.

With a broad sampling of the culture on the lower terrace thus completed, we were now confronted with a new question. Since both terraces across the site were marked by house pits, what were the pos- sibilities for relative dating and culture change inherent in these two distinct lev- els? This involved a geological question which has not yet been given much expert attention in Newfoundland. During the last glacial period the island was com- pletely submerged beneath the ice sheet, and the magnitude of this weight was so great that the land was depressed. Current geological theory holds that later, as the ice retreated and melted away, the land began to spring back toward its previous elevation. This process of upwarping was not an even, steady one, but rather a spo- radic and jerky series of movements inter- spersed with periods of stability. During each of these stable cycles the wave action of the sea had time to carve out a beach with an attendant offshore bar, and thus the coastline today is marked by a visible succession of steps, or old sea-cut beaches, that have been elevated far above the pres- ent strand line. Actually, these raised ter- races represent a progression in time: the highest of them is the oldest, and the low- ermost the youngest. If cultural remains were to be found on several of the ter- races, it might be that they too followed this sequence of time. There might be adaptive changes in artifacts from one beach level to another, indicating a shift in culture. Here was a hypothesis that would require testing by extensive and careful excavation.

We moved then to the upper terrace, 30 feet above sea-level, and cut another 50-foot trench at the eastern end of the site. This passed across the fronts of house pits numbered 1 and 2 on the sketch map, and the interior of No. 1 was also dug in the same fashion as the dwelling on the lower terrace. On the higher level our finds were substantially the same as be- fore, although there was a definite reduc- tion in quantity. We noted, too, that there were some differences in the workmanship on the artifacts; certain of the types were cruder and less skillfully made. One type in particular, a beautifully chipped flint knife with side notches, which had been fairly common on the lower terrace, did not appear here at all. All characteristics of the house pits, however, were the same for both levels. Such observations, of course, could not be completely evaluated in the field, and the material had to be cataloged and packed away for transit home. As soon as the sampling of the up- per terrace was complete, our time in this area of the coast was spent, and we shifted our base camp for reconnaissance else- where.

The end of each summer's expedition has seen us arriving home more heavily laden than when we left, our ration tins eaten empty but weighted instead with the stone and bone remains of an extinct culture. Now the work has entered a new phase. The data have been gathered, and at present they are being sorted and ana- lyzed. This will involve a separate study of each site, then a comparison of the mate- rial from different sites, and finally an analysis of the finds that were made on varying raised beach levels. With pain- staking care we may be able to reconstruct much of the Cape Dorset Eskimo economy, and perhaps trace their derivation from an earlier brethren who once left Asia in search of life in the New World.

From the study of these poor bits of cultural debris, which once were so im- portant to the survival of human lives, may come a deeper understanding of how one group of men strove for existence on the rugged periphery of the arctic. When the job is done, one more link will have been added to our chain of knowledge of the men of the north who, with primi- tive simplicity and ingenuity, perfected the techniques of living in a polar environ- ment, those same techniques which mod- ern man, despite his science, has had to adopt in order to achieve success in his own explorations of the arctic.

LEFT, LABRADOR CAMP SITE ON THE STRAIT OF BELLE ISLE. RIGHT, THE NEWFOUNDLAND OUTPORT OF IRELAND BIGHT

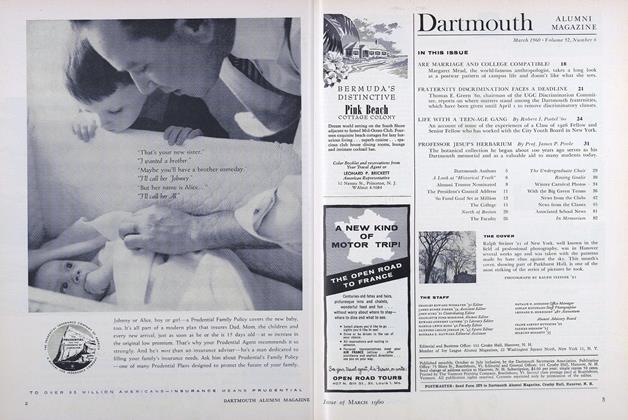

PROFESSOR HARP'S SKETCH MAP OF THE NEWFOUNDLAND EXCAVATION SITE

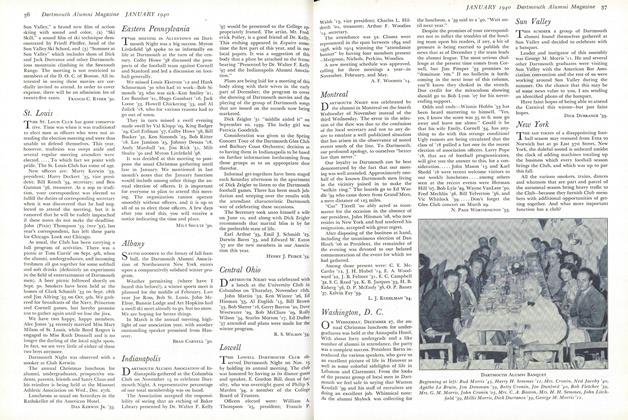

A YOUTHFUL ASSISTANT in the digging operates at Port au Choix-2 was Jackie Harp, 9, shown helping his father uncover buried culture one of the house pits left by the Cape Dorset Eskinmo.

Dartmouth College is increasingly identified with research in the arctic regions of North America. This past summer, while Captain David C. Nutt '4l led a sea-going expedition to north- ern Labrador waters aboard the BlueDolphin, Elmer Harp Jr., Curator of Anthropology in the Dartmouth Mu- seum, headed for Newfoundland on a different mission, also supported by the Arctic Institute of North America. Through his archeological detective work, Professor Harp seeks to recon- struct the story of an extinct Eskimo tribe and perhaps forge a new link in the hypothesis that the Cape Dorset Eskimo, as they are called, derived from earlier migrants who moved into the New World from Asia about 2,000 years ago. The editors have asked him to write this article so that alumni may know more about these interest- ing developments centering in the Dart- mouth Museum.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

November 1950 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, DAVID L. GARRATT -

Class Notes

Class Notes1905

November 1950 By GEORGE W. PUTNAM, GILBERT H. FALL -

Article

ArticleConvocation Address

November 1950 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

November 1950 By TRUMAN T. METZEL, COLIN C. STEWART 3RD -

Article

ArticleAssociated School News

November 1950 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1948

November 1950 By M. ROBERT HERRICK, RICHARD H. GREENE