by Harold J. Berman'38. Harvard Press, 1950, 522 pp., $4.75.

This is not a systematic study of Soviet Law, but an attempt at a broad interpretation of the Soviet legal system: its sources, its development, its significance for Russia and the West. The author is at present an Assistant Professor of Law at Harvard.

"A system of law and a system of force," Mr. Berman states in the introduction, "exists side by side in the Soviet Union." The author's aim is "to show the relationship between force and law in the Soviet system but not to "attempt to describe the Soviet system of force in any detail." In the whole book there are, in fact, only a few pages devoted to the treatment accorded to political susnects and "enemies" of the State.

Mr. Berman's interpretation of Soviet Law is implicit in the three subdivisions of his book: Part I, Soviet Law; Part II, Russian Law: Part III, Parental Law. In the first part, he sketches the evolution of the Marxist theory of law, from the assumption that law is "a Bourgeois fetish" and that, with the abolition of the class struggle, it will wither away, to the Stalinist concept of "stability of law." "Law—like the State—will wither away," Vishinsky stated in 1938, "only in the highest phase of Communism with the annihilation of capitalistic encirclement." Since the middle 30's, as a result of this new theory, there has begun a wide restoration of law in the Soviet Union and its extension to the most intimate social relations. The Marxist theory alone, however, does not "explain" Soviet Law; its one source is the Soviet system of planned economy, yet "it is not merely Socialist law, it is Russian Law."

In the second part of the book—perhaps the weakest because of questionable generalities and overdrawn historical parallels—the author discusses the heritage of 1,000 years of Russian legal history. His conclusion is that Soviet Law is "rooted and grounded in the Russian past." "The tradition of autocracy," "social solidarity," and "universal service" are some of the elements of Russia's past which the author maintains have influenced the development of the Soviet legal system.

Out of a blending of the Marxist theory and Russian history, there emerges, according to Mr. Berman, a new type of law, "parental law." This "new type of law," discussed in the third part of the book, is characterized by an emphasis on the educational role of law; it is a system in which the law "plays the part of a parent or guardian," and the State is primarily interested in "training the people to be loyal, moral, conscientious, responsible citizens." Mr. Berman believes that in this development lies the significance of Soviet Law for Russia and the West.

The book is well written and contains information on many distinctive features of the Soviet legal system. As to its broader implications, many students of Russia, including the present reviewer, would still maintain, contrary to Mr. Berman's contention, that Soviet Law is the product of the changing political needs of the All-Union Communist Party and that it reflects expediency rather than any abiding principles of justice.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

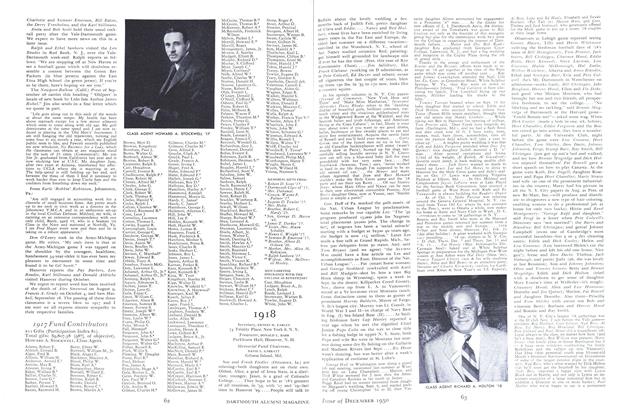

December 1950 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1935

December 1950 By HENRY R. BANKART JR., JOHN WALLACE, ROBERT w. NARAMORE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1942

December 1950 By JAMES L. FARLEY, JOHN H. HARRIMAN, ADDISON L. WINSHIP II -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

December 1950 By TRUMAN T. METZEL, COLIN C. STEWART 3RD, LEON H. YOUNG JR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1934

December 1950 By JOHN J. FOLEY, JOHN E. GILBERT, WILLIAM H. SCHERMAN -

Article

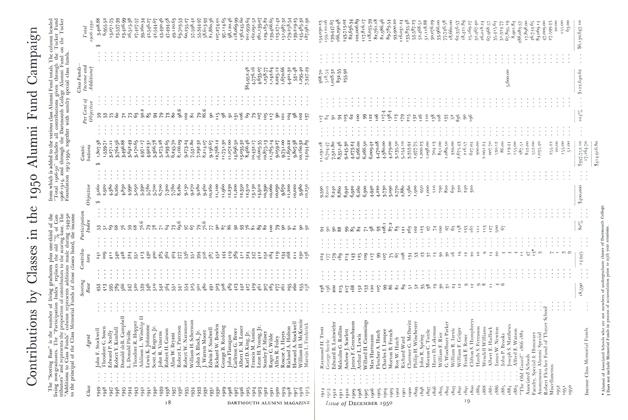

ArticleContributions by Classes in the 1950 Alumni Fund Campaign

December 1950

DIMITRI VON MOHRENSCHILDT

Books

-

Books

BooksThe Underside

October 1980 By A. Roger Ekirch '72 -

Books

BooksUnwilling Scepticism

APRIL 1983 By Freya von Moltke -

Books

BooksIntrepid History

DECEMBER 1982 By J. Craig Kuhn '42 -

Books

BooksA SWINGER OF BIRCHES:

June 1957 By JAMES M. COX -

Books

BooksRAILROAD CONSOLIDATION

JUNE 1930 By Nelson Lee Smith -

Books

BooksTHE GOOD PHYSICIAN.

JULY 1963 By S. MARSH TENNEY '44, M.D.