If you live up here in New Hampshire or Vermont you can't escape Robert Frost. He knew it all, said it all, all there is to know or say, about this hardscrabble granite chunk of New England that you alternately, often simultaneously, love and curse. If you live up here you don't even have to remember the Frost poems, not consciously. The country remembers them for you; the lines come unbidden. The ordinary sights, the common uneventful events: You see, you hear, and suddenly there they come, those Frost lines, tumbling back into consciousness from heaven knows where.

You pass a January woods; it's snowing - "Whose woods these are I think I know. ..." And maybe you stop a moment while the rest of the poem wells up. You cut your wood; be careful, be warned - "The buzz saw snarled and rattled in the yard. ..." You see, one summer's day, a long-abandoned set of tumbledown farm buildings back a dirt road - "... One had to be versed in country things not to believe the phoebes wept." You watch your thin New England spring defy the odds, late like as not, reluctant to leaf, slow to affirm - "Nature's first green is gold ... So dawn goes down to day. ... " Your ear picks up the cadence of a north country voice in the post of- fice or the hardware store - "I doubt if even his mother could tell him, 'Sakes, it's only weather.' He'd think she didn't know."

It is this quintessential Frost, the part that keeps coming back, the New England Frost, that Jones and Bradley .capture in their handsomely produced book. They do it in three ways: directly, by allowing the poet to speak for himself in no less than 53 of his own New England poems; in images, by 24 of Jones's remarkable color photographs; and in prose, by Bradley's biographical text which, for all its factual underpinning of dates and places, is primarily concerned with charting the poet's inner weather as he worked his way, slowly and late, toward an understanding of his craft and of the poetry inherent in his chosen land and its people.

Jones and Bradley's thesis is not startling. New England was indeed, as their subtitle suggests, Robert Frost's "source," his spiritual home where, when he had to go there, they had to take him in. They took him in, that's true, but there would seem some parochialism in assuming that in saying that you've said the whole truth. For in the end Robert Frost's poetic achievement, as Bradley affirms, transcended its "source." Frost is not just a New England poet, not in that too easily accepted, cozy, regional sense. He is an American poet, "the first American poet," as Robert Graves recognized, "who could honestly be reckoned a master-poet by world standards."

Literally speaking, Robert Frost was not even from New England. He was, as they say, from away. As far away as California, where he was born (in San Francisco) and where he lived until he was nearly 12. Having moved back east with his mother after the early death of the father, Frost spent the next 14 years in Lawrence, Massachusetts (New England, to be sure, but hardly Frostian New England). By 1900, then, when he came up to the farm in Derry, New Hampshire, and set about making New England genuinely his own, Robert Frost was already 26 years old. He was adrift. He had worked desultorily over the years as shoemaker, mill hand, news reporter, and teacher. He was married, a family man, but he and his wife took with them to Derry only one of their two children; their first-born, a son, lay newly buried back in Lawrence, dead of cholera infantum. Both Frosts, Robert and Elinor, were already acquainted with the night. He was writing poems, when and where he could, but when he moved to Derry Robert Frost had published precisely one poem. He was not yet a poet. New England would make him one. He and New England together.

Early 20th-century New England was a stern teacher, but what it had to teach neatly fitted the temperament of its poetic pupil. The first lesson it offered Frost, as Bradley notes, was "how to listen to other people." The poet was receptive. The intonations, the cadences of those New Hampshire voices, they stuck in his mind's ear, and a "revelation" - the word is Bradley's - was at hand. "Wasn't there something special in the sounds of voices? . . . The voice showed how a person carried himself into trouble, or through trouble; it was like a gesture of anger or defiance or hopelessness, whatever. Was it not character speaking?" The poet listened and, having heard, began to record the sounds of sense. And thus he began to give back, transmuted by the alchemy of poetry, "all the conflicting emotions - cruelty, fear, love, anger, friendship, frustration, tenderness - which can be heard in the way voices shape themselves into meaning." He began to give back to New England its own poetry.

New England also gave Robert Frost his people, those farmers, woodsmen, artisans, hill wives who speak his poems for him. They were rural people, those New Englanders Frost lived among in Derry or Franconia, and they were subtle, complex. They were as dogged as they were tough-minded. They had to be. They were, after all, survivors in a land where survival came hard. And again the poet and his chosen land meshed as naturally as tongue and groove as Frost came slowly to understand that his New England neighbors actually embodied an important precept about poetry - or at least about his poetry. He chose to write about rural people, as Bradley remarks, "not because they were better than other people . . . but because rural life was simpler, plainer to see. All*.the range and variety, intensity and subtlety of human emotions were here. He could see it in the mute longings of children, in the terrible wastings of stifled women."

Frost came to be well versed in country people. What his eye saw, his ear heard, and his pen recorded of them was often as not somber; but then so were the people, many of them, as somber as the land that had nurtured and shaped them. From the outside, rural New Hampshiremen and Vermonters often seem taciturn, antic "characters." "Quaint" is the usual word; ask any Massachusetts tourist. But Frost saw them from the inside; he knew better. So does Bradley: "New England was thought by outsiders to 'build character.' It didn't. It broke your back. You had to have character (or money from outside) to survive."

Finally, New England gave Frost his settings, those elemental physical backdrops against which to stage his human dramas. Frost was not temperamentally given to noting the spectacular, least of all the "romantic." And so once again there came that neat conjoining of poet and place. For New England proffered precisely those kinds of physical settings which Frost most valued poetically: plain, spare settings, mountains, woods, brooks, granite, storms, birches, snow. Above all, the New England snow:

Always the same, when on a fated nightAt last the gathered snow lets down as whiteAs may be in dark woods, and with a songIt shall not make all winter longOf hissing on the yet uncovered ground...

Like his people, Frost's settings too seem often as not bleak. Just how bleak we sense visually from Jones's photographs in this book. It is the photographs which establish the tone for the accompanying poems and text, and they largely depict, as I look at them, the wintry, somber texture and hue of Frost's New England. A hilltop farmhouse in gray winter dusk, sheet ice bending down the eaves, barn Aslant leaning into the teeth of a January storm; an unpainted shed all but collapsed, roof mostly gone, but with one sagging end still propped up, the work of human hands hoping to stave off the inevitable, maybe, for another year; the rural burying grounds of New England - four photographs of these - their lichened headstones eroded nearly smooth, leaning, sagging slowly into the dark weeds and oblivion. Such are the photographs, beautiful in their way; but the question that they frame in images, not words, is what to make of a diminished thing. And that is proper; it catches the tone. A good many of Frost's New England poems imply, as one asks outright, the selfsame question.

Over many years as a teacher I undertook to introduce many students - hundreds, I suppose - to Robert Frost's poems. I particularly enjoyed reading them with undergraduates, beginning readers new to Frost, fresh even to poetry itself. I wish I had had Jones and Bradley's book back then. Its cost aside (not many of my students could have afforded it, I fear), it would have been pedagogically irresistible. First to the poems themselves, then to Bradley's text, and then a look - a long, contemplative look - at Jones's images of Frost's New England. And then, finally, back to another reading of the poems themselves. This book would have made it all so much easier - and so much more rewarding for those beginning readers of Frost. For with the possible exception of an extended shunpike tour through Robert Frost's New England itself, the complete Poems in hand, I find it hard to imagine a better introduction to the poet and his New Englandness than is afforded by Jones and Bradley's book.

ROBERT FROST:A TRIBUTE TO THE SOURCEPoems by Robert Frost '96, photographs byDewitt Jones '65, text by David Bradley '38Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1979. 165 pp. $20.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

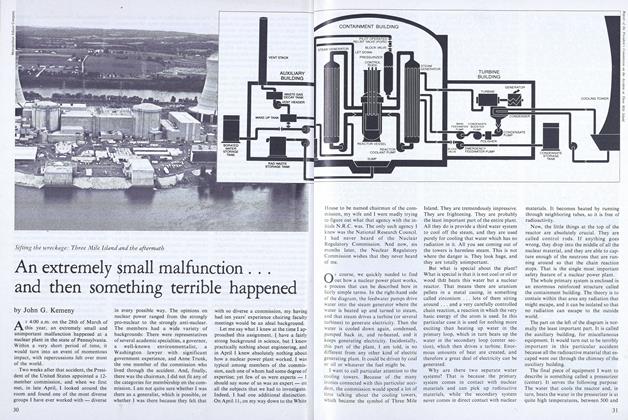

FeatureAn extremely small malfunction ... and then something terrible happened

December 1979 By John G. Kemeny -

Feature

FeatureThe Medical Legacy of August 1945

December 1979 By Stuart C. Finch -

Feature

FeatureGiving and Getting

December 1979 By Mary Ross -

Article

ArticleAn Old-fashioned Mutant

December 1979 By MICHAEL COLACCHIO '80 -

Article

ArticleThe Five-Year Plan

December 1979 By MICHAEL COLACCHIO '80 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1954

December 1979 By JOHN L. GILLESPIE

R.H.R.

-

Books

BooksNotes on a common bond: the federal city, that summer in Philadelphia, Essex County in revolt, and disaster in Ohio

September 1976 By R.H.R. -

Books

BooksMonticello to Montmartre

November 1976 By R.H.R. -

Books

BooksCity Views

April 1977 By R.H.R. -

Books

BooksNotes on a Pulitzer not given and on Dr. Bob, a gruff, humane Yankee who helped found AA

JUNE 1977 By R.H.R. -

Books

BooksObserving Life

JAN./FEB. 1978 By R.H.R. -

Books

BooksNotes on a Yale man's journal and the 'elbowing self-conceit of youth.'

MARCH 1978 By R.H.R.

Books

-

Books

BooksHAWAII WITH SYDNEY A. CLARK,

June 1939 By Alexander Laing '25 -

Books

BooksTHE SYSTEMATIC THEOLOGY OF PAUL TILLICH: A REVIEW AND ANALYSIS.

JULY 1965 By DAVID H. KELSEY -

Books

BooksTHE SOCIAL FUNCTIONS OF EDUCATION

May 1937 By Irving E. Bender -

Books

BooksTHE DRAMA OF UPPER SILESIA

June 1936 By John G. Gazley -

Books

BooksMATHEMATICS IN MEDICINE AND THE LIFE SCIENCES.

OCTOBER 1966 By JOHN PHILIP HENRY, M.D. -

Books

BooksPHILIP THE FAIR AND BONIFACE VIII: STATE VS. PAPACY

JUNE 1967 By JOHN R. WILLIAMS