Activities of Army Explorer-Engineer, Graduate of 1809, Aided in the Development of the West

LIKE MANY A MAN who has contributed to the history of the West, Stephen Harriman Long, 1809, was of New Hampshire origin. His ancestors were sturdy Dissenters who fled to Scotland during the reign of James II or settled in Massachusetts during the early years of the Eighteenth Century. Stephen's grandfather removed to Hopkinton, N. H., and it was there that the future explorer was born on December 30, 1784. His father had enlisted in the Revolutionary Army at the age of 16 and had had the distinction of witnessing the surrender of Burgoyne's army at Saratoga and Washington's profanity at Monmouth.

Stephen Harriman Long was the eldest son in a group of 13 children born to Moses Long and Lucy Harriman. The lad learned the trade of his father, who was a cooper, and grew up in the atmosphere of a New England hill farm. The annual period given over to education must have been small. It is known that his younger brother Enoch attended school two months each winter and it is doubtful if Stephen had any longer period of schooling. Evidently young Stephen made the most of his opportunities for he was graduated from Dartmouth College in 1809.

After teaching a few years, he chose the army for his career and became a lieutenant of engineers. In 1815 he was appointed assistant professor of mathematics at West Point. Breveted major in the Topographical Engineers, he was given the task of surveying the upper Mississippi Valley, making plans of existing fortifications and choosing sites for new forts.

Accordingly Major Long collected a crew at Fort Crawford (Prairie de Chien) and in 1817 ascended the Mississippi to the Falls of St. Anthony. There were no exciting circumstances. The Indians were friendly and even displayed the American flag upon his approach. He made his explorations, observed the natural curiosities of the vicinity and speedily returned to Prairie de Chien, having been absent about 13 days. Floating down the river, he examined various sites for fortification. During 1817 and 1818 he travelled extensively in the Southwest between the Arkansas and Red Rivers.

On March 3, 1819, Major Long married Martha Hodgkins of Philadelphia and hastened off to the West once more, "having started upon his first famous Rocky Mountain expedition before his honeymoon was fairly over."

This was the project known as the "Yellowstone Expedition." The purpose was to garrison the posts in the Northwest and hold the Indians in check. Because the War of 1812 had been fought such a short time before, it was feared that the Indians might be still susceptible to British influence. An added objective was the protection and extension of the American fur trade. The expedition was to have military and scientific branches but the military side of the affair was such a resounding failure that a Congressional investigation ensued. When the way was finally cleared for the scientific arm of the expedition, Major Long found himself with a much abbreviated force and objective.

The commander assembled his party in Pittsburgh in April 1819. The personnel included a botanist, a geologist, an artist, and two topographers. Calhoun, then Secretary of War, warned the explorers "to acquire as thorough and accurate knowledge, as may be practicable, of a portion of our country which is yet imperfectly known. With this in view, you will permit nothing worthy of notice to escape your attention You will enter in your journal everything interesting in relation to soil, face of country, water courses and productions, whether animal, vegetable or mineral."

It will be remembered that this was the period of the "steamboat craze" and a boat of special design was constructed and named the Western Engineer. Launched in Pittsburgh in 1819, it was probably the first stern-wheel steamboat ever built. Well armed and fantastically decorated, this vessel made a decided impression upon the uninitiated Indians and frontiersmen. The Western Engineer and its passengers left Pittsburgh on May 5, 1819, and journeyed down the Ohio and up the Mississippi to St. Louis, whence they proceeded up the Missouri River. An interesting commentary on the efficacy of steamboat exploration is seen in the fact that some members of the party went by land and had no difficulty in keeping up with those aboard the Western Engineer. At Charaton the last frontier was reached. One pioneer, already 60 years old, eagerly questioned the party concerning the upper reaches of the River Platte and had serious intentions of removing thither. They pondered upon the "manifest propensity, particularly in the males, to remove westward," but were reminded of the dictum of Daniel Boone: "I think it is time to remove when I can no longer fell a tree for fuel, so that its top will be within a few yards of my cabin."

The expedition proceeded up die river in two divisions. The land party while making a side excursion fell in with some Pawnees who robbed them of their equipment. By the middle of September the explorers had passed the mouth of the River Platte and had chosen a site for the winter camp. The scientists collected specimens and observed Indian life.

At this point, Major Long left camp and went to Washington. Here he found that the military scheme had been abandoned and there remained only a "small side show" to be undertaken in the direction of the Rocky Mountains. This time Congress was so niggardly with funds that the explorers had to furnish much of their own equipment.

On June 6, 1820, the explorers began a steady and uneventful progress up the River Platte. An attempt to vaccinate the Indians was unsuccessful. Soon they saw the first buffaloes. In a few days they began to catch glimpses of the distant Rockies appearing like cloud banks. By Independence Day they neared the present site of Denver. Once the mountain barrier was reached, the expedition turned southward. One towering summit has since been named Long's Peak. Five members of the party made an ascent of Pike's Peak and were probably the first whites to do so.

Major Long now divided his forces. One detachment under Captain Bell was to descend the Arkansas River. Long's group set out in search of the Red River. It was now midsummer and the weather was hot. Supplies ran low and the explorers were obliged to subsist on wild horseflesh. To add to their difficulties, water was not overabundant and it was not until September that they came upon running water once more. This proved to be the Canadian rather than the Red River. A few days later they met a white man who told them of Captain Bell's arrival at Fort Smith.

In making his report to the Secretary of War, Major Long created the fiction of the "Great American Desert"; at least he used the term in his report and on an accompanying map. The report was a disappointment to the public since general opinion was not a desire for a geological treatise but a dissertation on the availability of the region for settlement.

In 1823 the War Department appointed Major Long to the command of an exploring expedition in northern Minnesota. The object of this venture was to make a general topographical description of the region. The route was to be up the Minnesota River, thence down the Red River to the 49th Parallel. Long was accompanied by four scientists and a squad of soldiers. At the Falls of St. Anthony they were joined by an Italian freelance, Constant ino Beltrami. Pushing up the river, the expedition soon left the forests behind and emerged upon the open prairies. Crossing over to the headwaters of the Red River, the explorers descended that stream to Pembina, one of Lord Selkirk's settlements. Suspecting that Pembina was south of the international boundary, Long determined the latitude and found the town to be within the borders of the United States. Thereupon, he took possession of the com- munity for the American Republic.

Although Long's instructions had prescribed a route eastward along the 49th Parallel, this region proved much too swampy to be practical. Exchanging their horses for canoes, the members of the expedition continued down the Red River. Passing Fort Douglas, in due time they floated out upon the waters of Lake Winnipeg. Skirting the shore they entered the Winnipeg River and continued up this stream to the Lake of the Woods. From this body of water they continued by numerous portages to Lake Superior. Here they refitted an old boat which had been abandoned by the Boundary Line Commission and made their way to Mackinac. At this point Long boarded the revenue cutter Dallas for Detroit and thence continued by water route to Philadelphia via the Erie Canal.

In his report, Major Long continued his theme of the "Great American Desert." He guessed entirely wrong on the Red River Valley, for he considered this future wheat region as sterile and its flatness as a "defect in its natural character that cannot be easily remedied."

In 1826 Long was promoted to Brevet Lieutenant Colonel for ten years of faithful service in the same grade. At this time he made a reconnaissance for a National Road from Buffalo to Washington and an- other from Zanesville, Ohio, to New Orleans. He was called in to assist in a survey of that early railroad, the Baltimore and Ohio. In the early 1830's he continued to work in the field of internal improvements: a reconnaissance of a National Road from Portsmouth, Ohio, to Linville, N. C.; railroad surveys from Charleston to Memphis, Knoxville to Memphis, Fredericksburg to Abington, Va.; and Concord, N. H., to White River, Vt.; a survey of the Holston, French, Broad, and Tennessee Rivers; and a survey for a railroad in Maine.

For some reason Colonel Long returned to his native town of Hopkinton for two years in the middle 1830's and lived in the Kimball house. In this interlude Long patented his improved method of constructing bridges. His brother, Dr. Moses Long, was general agent for their sale. Among such bridges constructed was the one at Haverhill, N. H., and on the National Road in Illinois and the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad.

Colonel Long was next transferred to the South where he engaged in a survey of the Western and Atlantic Railroad and brought out a manual on railroad construction, the first of its kind. Each succeeding year found him busy in some part of the country. He examined the harbors of Maine; he was a member of a board for selecting a site for a national armory; he was the topographical engineer for the improvement of western rivers; he planned and constructed four marine hospitals; and he built steamers for use in the Mexican War.

During the last decade before the Civil War, Long was connected with western improvements, first as board member and later in charge of operations. He made surveys for a canal around the Falls of the Ohio and for the improvement of the lake harbors. He dredged the Southwest Pass of the mouth of the Mississippi River and installed jetties, but they were too frail. He removed obstructions in the Red River and built roads in Kansas and Nebraska.

Upon the outbreak of the Civil War, Long was appointed Chief Engineer in the Bureau of Topographical Engineers. During the conflict he superintended improvements on Lake Ontario. In 1863, he retired from active service having been on the army register over 45 years. Death came at Alton, Ill., September 4, 1864.

The career of Stephen Harriman Long is connected with the story of the West, first as an explorer and secondly as an instrument for promoting internal improvements. The examinations and surveys which he made took him over extensive areas of the United States. All in all, the negative tenor of his exploring reports was probably counterbalanced by his engineering undertakings which were an aid to western progress.

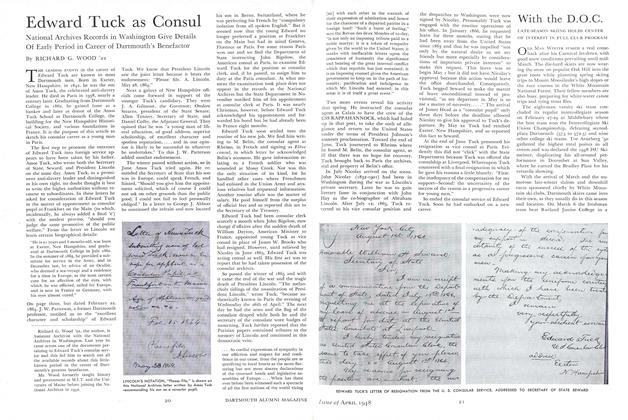

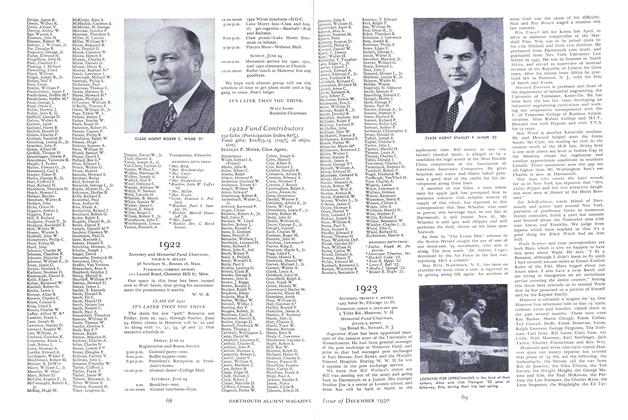

STEPHEN HARRIMAN LONG, 1809, pictured as Chief of the Topographical Engineers in 1861.

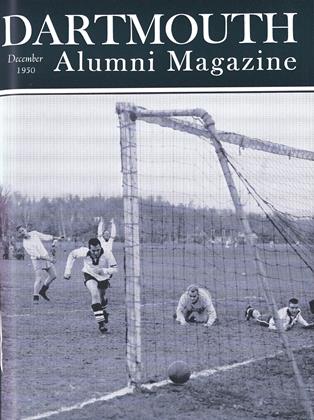

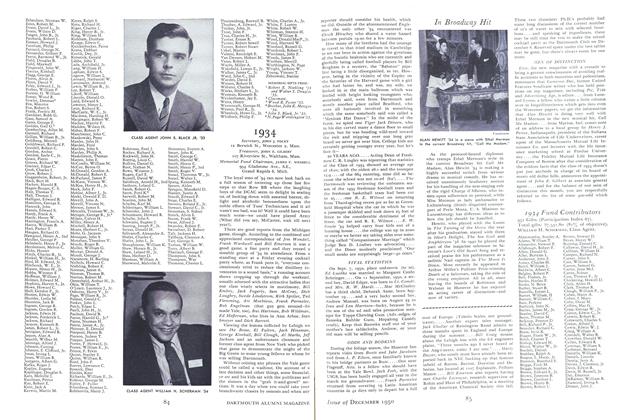

TWO PLAYS THAT PRODUCED DARTMOUTH'S FIRST TOUCHDOWN AT HARVARD: Left, Bill Roberts (34) plunges to the 1-foot line and, right, Johnny Clayton goes over on a quarterback sneak. Clayton later skirted end for another score and with Dick Collins on the receiving end completed a 28-yard pass play for a third touchdown in the 27-7 victory.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

December 1950 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1935

December 1950 By HENRY R. BANKART JR., JOHN WALLACE, ROBERT w. NARAMORE -

Class Notes

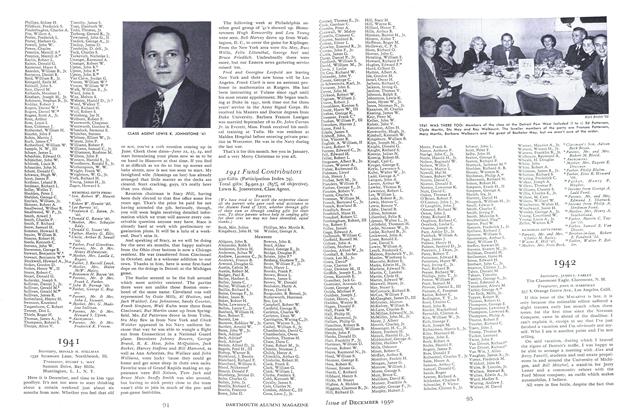

Class Notes1942

December 1950 By JAMES L. FARLEY, JOHN H. HARRIMAN, ADDISON L. WINSHIP II -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

December 1950 By TRUMAN T. METZEL, COLIN C. STEWART 3RD, LEON H. YOUNG JR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1934

December 1950 By JOHN J. FOLEY, JOHN E. GILBERT, WILLIAM H. SCHERMAN -

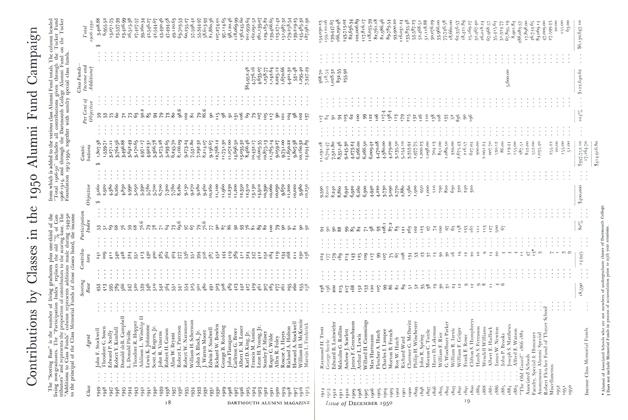

Article

ArticleContributions by Classes in the 1950 Alumni Fund Campaign

December 1950