National Archives Records in Washington Give Details Of Early Period in Career of Dartmouth's Benefactor

THE LEADING EVENTS in the career of Edward Tuck are known to most Dartmouth men. Born in Exeter, New Hampshire, in 1842, he was the son of Amos Tuck, the celebrated anti-slavery leader. He died in Paris in 1938, nearly a century later. Graduating from Dartmouth College in 1862, he gained fame as a banker and later as donor of the Amos Tuck School at Dartmouth College, the building for the New Hampshire Historical Society, and various foundations in France. It is the purpose of this article to sketch his consular career as a young man in Paris.

The first step to promote the entrance of Edward Tuck into foreign service appears to have been taken by his father, Amos Tuck, who wrote both the Secretary of State, Seward, and President Lincoln on the same day. Amos Tuck, as a prominent anti-slavery leader and distinguished in his own right, no doubt thought it best to write the higher authorities without recourse to subordinates. In these letters he asked for consideration of Edward Tuck in the matter of appointment as consular pupil at Frankfort on the Main (to which, incidentally, he always added a final 'e') with the modest proviso, "should you judge the same promotive of the public welfare." From the letter to Lincoln we learn certain biographical details:

"He is 21 years and 6 months old, was born at Exeter, New Hampshire, and graduated at Dartmouth College in July 1862. In the summer of 1863, he provided a substitute for service in the Army, and in December last, by advice of an Oculist, who deemed a sea-voyage and a residence for a time in Europe, as the most certain cure for an affection of the eyes, with which he was afflicted, sailed for Europe, and is now in France or Germany, with his eyes almost cured."

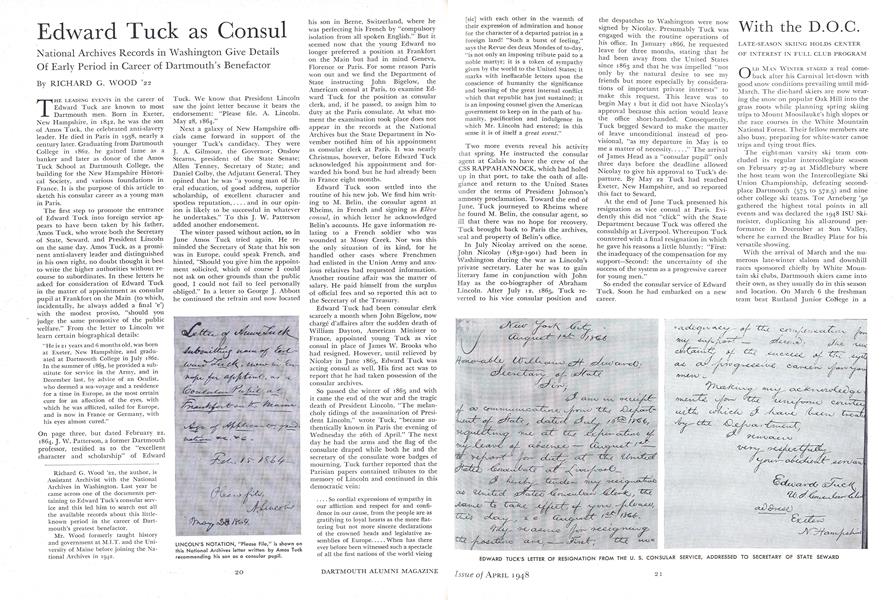

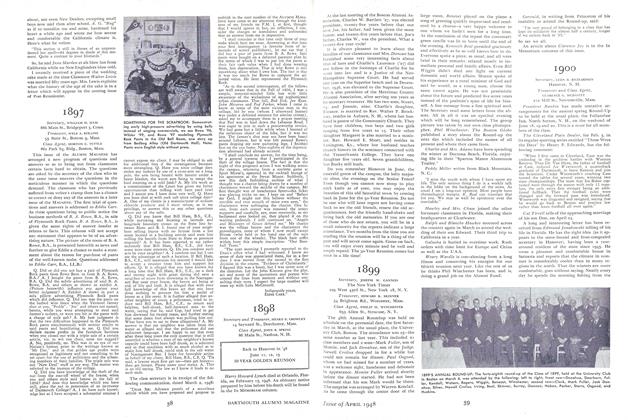

On page three, but dated February 22, 1864, J. W. Patterson, a former Dartmouth professor, testified as to the "excellent character and scholarship" of Edward Tuck. We know that President Lincoln saw the joint letter because it bears the endorsement: "Please file. A. Lincoln. May sB, 1864."

Next a galaxy of New Hampshire officials came forward in support of the younger Tuck's candidacy. They were J. A. Gilmour, the Governor; Onslow Stearns, president of the State Senate; Allen Tenney, Secretary of State; and Daniel Colby, the Adjutant General. They opined that he was "a young man of liberal education, of good address, superior scholarship, of excellent character and spotless reputation, .... and in our opinion is likely to be successful in whatever he undertakes." To this J. W. Patterson added another endorsement.

The winter passed without action, so in June Amos Tuck tried again. He reminded the Secretary of State that his son was in Europe, could speak French, and hinted, "Should you give him the appointment solicited, which of course I could not ask on other grounds than the public good, I could not fail to feel personally obliged." In a letter to George J. Abbott he continued the refrain and now located his son in Berne, Switzerland, where he was perfecting his French by "compulsory isolation from all spoken English." But it seemed now that the young Edward no longer preferred a position at Frankfort on the Main but had in mind Geneva, Florence or Paris. For some reason Paris won out and we find the Department of State instructing John Bigelow, the American consul at Paris, to examine Edward Tuck for the position as consular clerk, and, if he passed, to assign him to duty at the Paris consulate. At what moment the examination took place does not appear in the records at the National Archives but the State Department in November notified him of his appointment as consular clerk at Paris. It was nearly Christmas, however, before Edward Tuck acknowledged his appointment and forwarded his bond but he had already been in France eight months.

Edward Tuck soon settled into the routine of his new job. We find him writing to M. Belin, the consular agent at Rheims, in French and signing as Eleveconsul, in which letter he acknowledged Belin's accounts. He gave information relating to a French soldier who was wounded at Mossy Creek. Nor was this the only situation of its kind, for he handled other cases where Frenchmen had enlisted in the Union Army and anxious relatives had requested information. Another routine affair was the matter of salary. He paid himself from the surplus of official fees and so reported this act to the Secretary of the Treasury.

Edward Tuck had been consular clerk scarcely a month when John Bigelow, now charge d'affaires after the sudden death of William Dayton, American Minister to France, appointed young Tuck as vice consul in place of James W. Brooks who had resigned. However, until relieved by Nicolay in June 1865, Edward Tuck was acting consul as well. His first act was to report that he had taken possession of the consular archives.

So passed the winter of 1865 and with it came the end of the war and the tragic death of President Lincoln. "The melancholy tidings of the assassination of President Lincoln," wrote Tuck, "became authentically known in Paris the evening of Wednesday the 26th of April." The next day he had the arms and the flag of the consulate draped while both he and the secretary of the consulate wore badges of mourning. Tuck further reported that the Parisian papers contained tributes to the memory of Lincoln and continued in this democratic vein:

.... So cordial expressions of sympathy in our affliction and respect for and confidence in our cause, from the people are as gratifying to loyal hearts as the more flattering but not more sincere declarations of the crowned heads and legislative assemblies of Europe When has there ever before been witnessed such a spectacle of all the first nations of the world vieing [sic] with each other in the warmth of their expression of admiration and honor for the character of a departed patriot in a foreign land! "Such a burst of feeling," says the Revue des deux Mondes of to-day, "is not only an imposing tribute paid to a noble martyr; it is a token of sympathy given by the world to the United States; it marks with ineffacable letters upon the conscience of humanity the significance and bearing of the great internal conflict which that republic has just sustained; it is an imposing counsel given the American government to keep on in the path of humanity, pacification and indulgence in which Mr. Lincoln had entered; in this sense it is of itself a great event."

Two more events reveal his activity that spring. He instructed the consular agent at Calais to have the crew of the CSS RAPPAHANNOCK, which had holed up in that port, to take the oath of allegiance and return to the United States under the terms of President Johnson's amnesty proclamation. Toward the end of June, Tuck journeyed to Rheims where he found M. Belin, the consular agent, so ill that there was no hope for recovery. Tuck brought back to Paris the archives, seal and property of Belin's office.

In July Nicolay arrived on the scene. John Nicolay (1832-1901) had been in Washington during the war as Lincoln's private secretary. Later he was to gain literary fame in conjunction with John Hay as the co-biographer of Abraham Lincoln. After July 12, 1865, Tuck reverted to his vice consular position and the despatches to Washington were now signed by Nicolay. Presumably Tuck was engaged with the routine operations of his office. In January 1866, he requested leave for three months, stating that he had been away from the United States since 1863 and that he was impelled "not only by the natural desire to see my friends but more especially by considerations of important private interests" to make this request. This leave was to begin May 1 but it did not have Nicolay's approval because this action would leave the office short-handed. Consequently, Tuck begged Seward to make the matter of leave unconditional instead of provisional, "as my departure in May is to me a matter of necessity " The arrival of James Head as a "consular pupil" only three days before the deadline allowed Nicolay to give his approval to Tuck's departure. By May 22 Tuck had reached Exeter, New Hampshire, and so reported this fact to Seward.

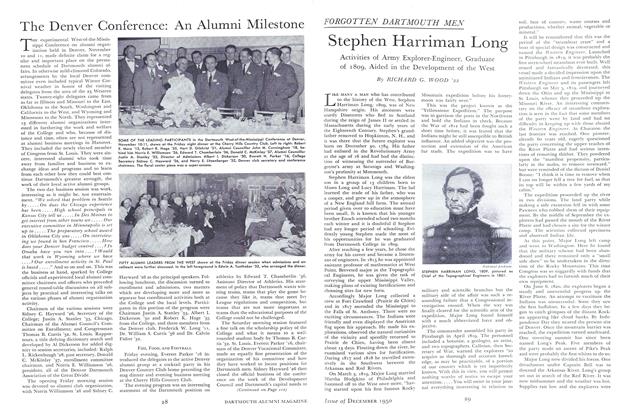

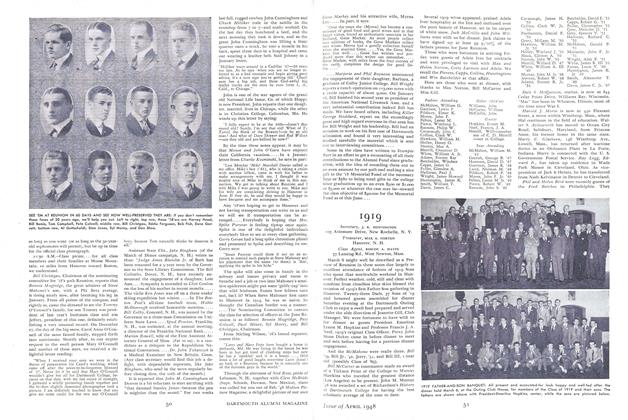

At the end of June Tuck presented his resignation as vice consul at Paris. Evidently this did not "click" with the State Department because Tuck was offered the consulship at Liverpool. Whereupon Tuck countered with a final resignation in which he gave his reasons a little bluntly: "First: the inadequacy of the compensation for my support—Second: the uncertainty of the success of the system as a progressive career for young men."

So ended the consular service of Edward Tuck. Soon he had embarked on a new career.

LINCOLN'S NOTATION, "Please File/7 is shown on this National Archives letter written by Amos Tuck recommending his son as a consular pupil.

EDWARD TUCK'S LETTER OF RESIGNATION FROM THE U. S. CONSULAR SERVICE, ADDRESSED TO SECRETARY OF STATE SEWARD

Richard G. Wood '22, the author, is Assistant Archivist with the National Archives in Washington. Last year he came across one of the documents pertaining to Edward Tuck's consular service and this led him to search out all the available records about this littleknown period in the career of Dartmouth's greatest benefactor. Mr. Wood formerly taught history and government at M.I.T. and the University of Maine before joining the National Archives in 1942.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleStumps and Scholarships

April 1948 By ROBERT S. MONAHAN '29 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1942

April 1948 By JAMES L. FARLEY, JOHN H. HARRIMAN, ADDISON L. WINSHIP II -

Class Notes

Class Notes1897

April 1948 By WILLIAM H. HAM, WELD A. ROLLINS, MORTON C. TUTTLE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

April 1948 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, DAVID L. GARRATT -

Class Notes

Class Notes1931

April 1948 By A. W. LAUGHTON, WILLIAM H. SCHULDENFREI, ERNEST H. MOORE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1919

April 1948 By J. K. HUNTINGTON, MAX A. NORTON, ROSCOE .A. HAYES