In last month's discussion of Dartmouth's revised admissions procedures for 1949-50 only incidental mention was made of the College Board examinations. The relation of these examinations to Dartmouth's Selective Process was deserving of fuller treatment, and we are glad to have the space in this issue to go back to the subject.

As most of our readers are aware, Dartmouth has never required applicants for admission to take the College Board examinations. The College has, however, been a member of the Board from its earliest years and has made use of College Board scores in studying the predictive value of the examinations in the cases of some of the men admitted to Dartmouth. At the time of the original decision to dissociate itself from the College Board system, Dartmouth felt that an applicant's overall school record, coupled with other information gathered under the Selective Process, was an adequate and a more trustworthy indication of a man's college potentialities than were the College Board examinations, which at that time were of a type to be passed successfully with cramming. There were other reasons then, having to do with secondary school resentment of the influence the College Boards exerted on their curricula and educational programs, with the disadvantage of the system to public school boys, and especially with the serious inroads that the College Boards would have made on Dartmouth's strong public school delegations, particularly in the Midwest and Far West, where College Boards caused even more alarm than in the East.

The report of the Committee on Admission states that there have been substantial changes in the College Board examinations in recent years and that it has been re-examining its position in relation to them. "The tests have greatly improved in predictive value," says the report. "They are now of an objective type for which specific cramming is not very effective. Public school students no longer seem to be at a serious disadvantage. The use of College Boards has been greatly extended among colleges in the Midwest and Far West, as well as in the East. Desirable applicants for Dartmouth would not be alarmed at being required to take the examinations, or under a disadvantage in taking them, to the degree that was previously the case. Actually, seventy per cent of the members of the Class of '953 took the College Board examinations, though not required to do so by Dartmouth."

This is the background against which Dartmouth has been re-examining its position relative to the College Boards. A study of the Class of 1951, for example, has shown that in the cases of the men who did take the examinations the College Board scholastic aptitude tests had an impressive correlation with grades achieved in the first semester of freshman year. This study of 1951 is being continued and a similar study of the Class of 1953 will soon begin. A good deal more than the predictive value of the College Board examinations is involved; Dartmouth's re-examination of its position must also assess such factors as the College's relationships with applicants, schools, alumni and the general public.

In view of Dartmouth's unique position relative to the College Boards, among the important Eastern colleges at least, the present studies and thinking of the Committee on Admission are of unusual interest. To Dartmouth men and others who might be inclined to view this re-examination with alarm, we quote the following from the committee report: "It is probably superfluous to add that the Committee's consideration of the possible future use of College Board examinations contemplates their employment as a supplement to, not a substitute for, our established procedures of selectiona supplement that might affect only a rather limited number of marginal candidates."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

February 1950 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Article

ArticleBack to Hanover in December

February 1950 By WILLIAM H. HAM '97 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1905

February 1950 By ROYAL PARKINSON, GILBERT H. FALL, FLETCHER A. HATCH -

Class Notes

Class Notes1943

February 1950 By ELMER G. STEVENS JR., STANTON B. PRIDDY, THEODORE R. HOPPER -

Article

Article"Of the People, By the People, For the People..."

February 1950 By EDWARD C. LATHEM '51 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1936

February 1950 By NORBERT HOFMAN JR., JOHN E. MORRISON JR., ROBERT L. PATERSON

C. E. W.

-

Article

ArticlePolitical Experiment Grows

June 1938 By C. E. W. -

Article

ArticleThe Reason Why

April 1944 By C. E. W. -

Sports

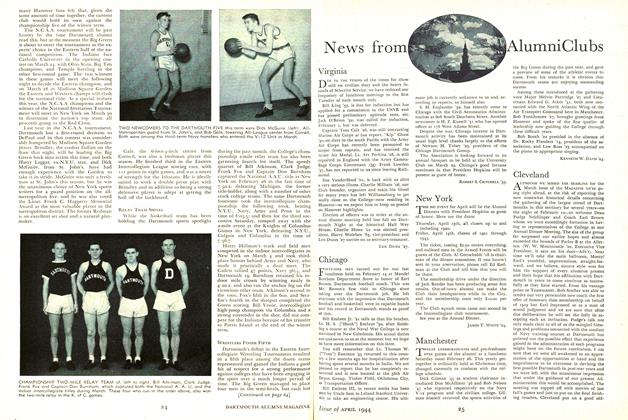

SportsWith Big Green Teams

April 1944 By C. E. W. -

Sports

SportsWRESTLERS FINISH FIFTH

April 1944 By C. E. W. -

Article

ArticleMiscellany

December 1949 By C. E. W. -

Article

ArticleFive-Star Final

November 1950 By C. E. W.

Article

-

Article

ArticleTHE DIARY OF WILLIAM SMITH OF CAYENDISH, VERMONT, A FRESHMAN IN DARTMOUTH COLLEGE, SEPT. 23, 1822-AUG. 3, 1823

January, 1911 -

Article

ArticleNominations to Council

February 1949 -

Article

ArticleJune Reunion Meetings

APRIL 1968 -

Article

ArticleA Fine Season, But Few Salutes

June 1974 -

Article

ArticleCabin Thief Caught

JANUARY, 1928 By "F. Clark S. '30." -

Article

ArticleGREEN HIGHLANDERS AND PINK LADIES.

MARCH 1972 By JOHN HURD '21