(Or, how I became Dartmouth's presidential nit-picker.)

Istood in awe of President Dickey '29—and why not? He was very tall. If you've read The Odyssey lately, you'll remember that superior height was a prime attribute of the old kings and nobles. The goddess Athene even used her divine powers to make Odysseus seem taller than he really was, whenever he most needed to make a good impression.

But it wasn't Mr. Dickey's stature that produced my awe. He seemed to me (and I think he really was no need for Athene to fake it for him) experienced, and forceful, and wise. One more factor: I wasn't a curmudgeon back in 1960,1 was an insecure young instructor in the English Department. Meek I was, and eager to please.

There came a night, though, when I wished passionately that Mr. Dickey had been less forceful. Robert Frost was in town, giving his annual reading to the freshmen. Every year Mr. Dickey invited four or five members of the faculty over to have a drink with Frost after the reading. Apparently he had been asking the same group of older men year after year, because Frost is supposed to have said, "Well, John, you have only five people on your faculty?"

Mr. Dickey took the hint, and that fall he invited three senior faculty and two juniors, of whom I was one. Frost was 86 at the time. When we all got to the president's house Frost seemed utterly exhausted. He sat nursing a rather large glass of scotch, not saying a word. The three senior profs kept a conversation going, and even we juniors occasionally piped up.

But it is not for nothing that scotch is called old man's milk. Frost revived. He instantly took the conversation over. For the next hour I got to hear the living poet I most admired. Then Mr. Dickey stood up. "Well, Robert," he said, "you must be tired. We should letyou go to bed." All five of us rose at once. Not Frost.

"Don't go," he said, looking at each of us in turn. "Sit backdown."

"I think we should let Robert get to bed," Mr. Dickey repeated. Frost rose, and came to each of us, even me. "Don't leave," he said. But Zeus had told us to go, and we did. I've often wondered what would have happened if we had sat back down. Would we have been hurled from Olympus?

John Kemeny is probably the smartest person I have ever met, and one of the two wittiest. (Who's the other? Anne Spencer Lindbergh, Charles's novel-writing daughter.) I actually liked to go to faculty meetings when Kemeny ran them. I thought he brought about the admission of women brilliantly, and once they were here it tickled me that this genius or near-genius couldn't pronounce the new gender's name. "Men and Vimmen of Dartmouth," he always said, addressing the students at Convocation. An occasional fallibility is endearing.

The Native American Studies program that he started is the most successful in the country. We all know which American college president moved with surest tread into the computer age. I could go on and on.

But Mr. Kemeny had, in my opinion, one less endearing fallibility. Sometimes he forgot his humanistic side, and operated quite narrowly as a mathematician. And when, in numbers mode, he reorganized the schedule of class meetings, or devised a D-plan with a thousand variations, the results were sometimes unfortunate.

When I arrived at the College it had recently shifted from two 15-week semesters to three 10 weekterms. Students now took just three courses at a time instead of the old five.

They were supposed, of course, to learn just as much in ten weeks as they previously had in IS. One way to make this happen was to schedule more classes per week. So we did. Instead of meeting three times a week, as in the old semester day, almost every course now met four times a week, except those that met five. In general the classes lasted 50 minutes.

Then President Kemeny had an arithmetical thought. 4 x 50 = 200. Two hundred minutes of class. But this total can be reached in other ways. 3x65 = well, not quite 200, but close. 195. Course times got reorganized so that while you still could teach four times a week for 50 minutes (and some profs continue to), it became much easier to. teach three 65s. Meeting thus appeals to the worst motives of both students and teachers. With a little planning you have classes only on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday. (I have often found it irresistible myself.)

Mathematically, 200 minutes in four slices is very close indeed to 195 minutes in three slices. In terms ofintensity and of attention span, however, they are noticeably different, especially in big courses. At least I found it so, teaching literature.

Mr. Kemeny also, I felt, made a mistake with all those D-plans. They worked against community. After freshman year the College ceased to be table d'hote and became a cafeteria. Or started to, anyway. Students found many ways to retain things like real senior year, and the harm was only modest. When I think of the many splendid things John Kemeny did, I feel almost like an ingrate even bringing schedules up. But that's what we curmudgeons are for: to be critical and to pick nits. (Joke I used to make in writing classes: What happens to people who don't pick nits? Answer: They become lousy. If you doubt it, look up "nit.")

David McLaughlin '54 did a number of wonderful things for the College. As far as I was concerned, the most wonderful was to close the cafeteria. Kemeny himself had already restored one bit of table d'hote, the sophomore summer, but now McLaughlin brought back the senior year. It is not too much to say that he restored order to what had begun to feel like chaos, because of the overabundance of choices. McLaughlin also did wonders for the look and the health of the campus. No deferred maintenance here.

But he also, in my opinion, made one strategic error. He tried to get the College to speak with one voice. It didn't always have to be his voice, it just had to be one. No public disagreements.

I can see where this kind of unanimity or apparent unanimity might be necessary in the staff of an American embassy or even in the whole State Department. (It does lead to the absurdity of assistant secretaries of state telling us, 20 years after it makes the least difference, how opposed they were to our Vietnam policy, and how they wrung their hands and wished it had been different.)

But it just doesn't work on college campuses, and the better the college the less it works. Dartmouth speaks with somewhere around 40,000 voices. A few of them, I admit, I'd be glad to hear less often, and probably I have colleagues who would be delighted if I talked less. It's not going to happen. We are going to go on like a vast swarm of bees in an apple tree at blossom time. That hum you hear is thought made audible.

Writing about Jim Freedman is rather tricky. I count both him and Sheba as friends. That's possible for me only because of my advancing age. If I had tried in 1960 to strike up a friendship with Mr. Dickey, I would have despised myself as a toady. But by the time Freedman took office, there was nothing I particularly wanted that a president of Dartmouth could give me. I already was a full professor. I'd already been on half-time for ten years (thus evading nearly all committee service). To enjoy the Freedmans as a couple who were fan to have dinner with, and to talk books and even basketball with that just seemed easy and comfortable. But it inhibits me now in writing.

Oh well. Here goes. Jim Freedman did a tremendous amount for the intellectual life of the College—and a college's primary life is intellectual. Has to be. If the center drifts elsewhere, the college gradually turns into a camp: boot camp, tennis camp, party camp, religious camp, whatever. Jim, with his presidential scholars, his encouragement of shared research where faculty and students do original work together, his open delight in almost all forms of knowledge, Jim was just what we needed.

In all ways but one, that is. Dartmouth is part of an educational tradition that goes back at least 2,300 years a tradition of out-door education. Twenty-three hundred years ago Aristotle taught philosophy and natural science to a bunch of students known as peripatetics. So called because they walked about in groves of trees as they learned philosophy and science. Afterwards, of course, they went to the gymnasium and did sports.

I wish Jim had been more interested in the College Grant, gone to the Ravine Lodge a little more, sat under a birch tree with his deans and talked education. In some ways New Hampshire is our campus quite literally from the lowest spot in the state to the highest. We do use it. We should use it more.

Four presidents. All four have played a role in making Dartmouth the really rather distinguished institution it is. When I took a job here, 38 years ago, one of my mother's friends expressed surprise. She was a grande dame type.

"You son's going to teach at Dartmouth" she said in her lofty way. "That's the sort of college one's dentist's children attend."

Besides being a snob, she was wrong about both Dartmouth and dentists. But that's besides the point. The point is that no one would dream of saying such a thing now.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureCOD and MAN at Dartmouth

September 1998 By David Dobbs -

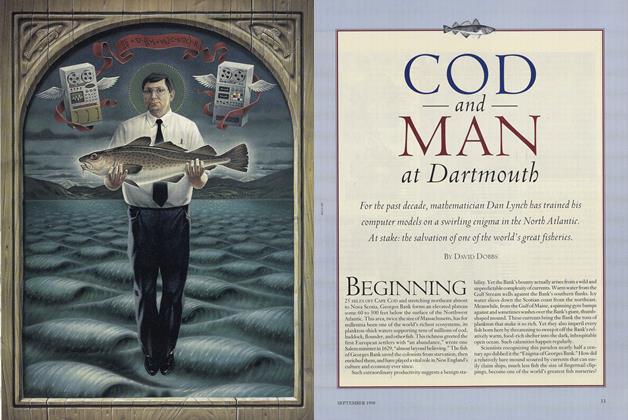

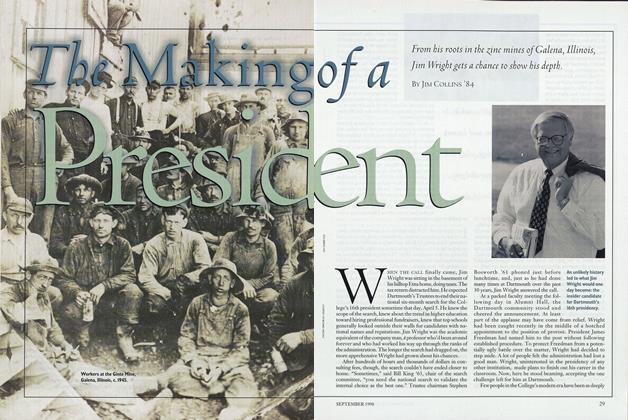

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Making of a President

September 1998 By Jim Collins '84 -

Feature

FeatureFOR REAL

September 1998 By Jana M. Friedman '94 -

Feature

FeatureFrom Rap to Ritual

September 1998 By Everett Wood '38 -

Article

ArticleThe Origin of Endangered Species

September 1998 By Kathleen Burge '89 -

Article

ArticleA Soggy Commencement

September 1998

Noel Perrin

-

Sports

SportsThe College's First Fan Picks a Winner

December 1989 By Noel Perrin -

Article

ArticleThe Faculty's Turn to Give

NOVEMBER 1996 By Noel Perrin -

Article

ArticleA Tale of Two Libraries

MARCH 1999 By Noel Perrin -

Curmudgeon

CurmudgeonThe Problem with the Dorm-Room Fridge

NOVEMBER 1999 By Noel Perrin -

CURMUDGEON

CURMUDGEONSkating on Thin Ice

MARCH 2000 By Noel Perrin -

Article

ArticleHow Green Is Dartmouth?

Sept/Oct 2003 By Noel Perrin

Article

-

Article

ArticleLIBRARY IN MEMORY OF PROFESSOR CHARLES F. RICHARDSON AT SUGAR HILL, N. H.

December, 1914 -

Article

ArticleMANCHESTER EDITORIAL PRAISES LATE DOCTOR C. P. BANCROFT

February, 1924 -

Article

ArticleArtistic Secretary

October 1947 -

Article

ArticleA Well-Named Ski Lodge

February 1955 -

Article

ArticleON RETIREMENT

JUNE 1964 By ALLEN R. FOLEY '20 -

Article

ArticleA Reply to Commencement Critics

June 1938 By JOHN B. STEARNS '16