Two weeks after the opening of College in 1881, a sturdy, dark complexioned young man straggled into Hanover, settled himself in quarters at Mrs. Gould's, and belatedly took up his studies as a member of the Class of 1885.

The tardy freshman was the younger son of Gen. Charles E. Hovey, a Washington lawyer and Dartmouth alumnus, who had distinguished himself as a soldier after leaving the presidency of an Illinois university to accompany his students into the Civil War.

The 17-year-old Dick was a brilliant lad, who at an early age had shown a marked ability as a poet; who had, in fact, already published privately a collection of his poems said to have been written between the ages of ten and thirteen. It is not surprising, therefore, that Richard Hovey immediately established himself as a man of letters among his classmates.

His earliest literary occupation in Hanover seems to have been the writing of "grinds" against the sophomores. While these rhymed derisions of the upperclassmen were enthusiastically applauded by his fellow freshmen, the "Sophies" failed to appreciate fully the artistic merit of his dedicatory verse, and their total lack of poetic discernment was forcefully demonstrated when it came time for initiations into the freshman societies.

Hovey records that on this occasion he received some very severe hazing, "but the other Freshmen got off very easily." He was blindfolded, perambulated around "Bedbug Alley" for about a quarter of an hour, and finally brought into the Sigma Ep Hall. Here he was announced as "Hovey! Hovey, the Poet," at which the assembled sophomores "hooted and yelled like demons."

"They put me through everything imaginable," he relates, "tossing me in a blanket, placing me on a block of ice and making me sit there, branding my hand with nitrate of silver, pouring water down my pants and other things too numerous to mention, among which was the recitation of an extempore poem by me."

Recognition of Hovey as an undergraduate poet was actually of an official nature, for at a meeting late in September he had been elected by acclamation titular poet of his class. Shortly after his election, he began writing the class song, which upon completion won the hearty approval of his classmates. "The Class of '85" first appeared in The Dartmouth and was later sung, to the tune of "It Was My Last Cigar," at the freshman supper in Montreal on Washington's Birthday, 1882. The third stanza will serve to illustrate the mood and tempo of the lyrics:

Like Eastern princes banqueting, We feast at learning's board, Where wisdom's meat is placed to eat And the wine of wit is poured; And when, as come it must, the hour Of parting shall arrive, Our last toast shall be Dartmouth And the class of '85.

Hovey had been in college hardly a month before he was scheming to find means of extending a forthcoming vacation. And by the time the "hill-winds" from the "still North" carried the message that winter had set in on Hanover Plain, the young Washingtonian was "on the warpath" and determined to get from "Prex" an extension of the recess, that he might "stay longer at home and avoid the coldest part of the winter here."

This is not at all to imply that Hovey did not like the out-of-doors. He merely did not, anymore than did his fellows, enjoy the bitter winter months. This was the Dartmouth of a day when students heated their own rooms by stoves or hearths; when the most appropriate winter recreation was truly "a song by the fire" with perhaps, occasionally, the other ingredients of fellowship mentioned in the song.

In the spring and fall, Hovey was fond of walking. He liked to "stroll down to the river via Stump Lane, Skunk Hollow and the Vale of Tempe," there "to lie on the carpet of needles always found beneath groves of pine or hemlock."

Also, he enjoyed such undergraduate escapades as going down to Norwich with a group to "raise the deuce," and he sets down with evident glee the following incident of the freshman year: "The examination in Latin was rather long and so, with great indignation, we proceeded in a body last Friday night to Johnny Lord's house and serenaded him with tin horns. He came out, made us a speech, gave us taffy and retired; and so did we, after singing 'Bye, baby, bye O!' to express our gratification."

Hovey was especially fond of Latin and read the odes of Catullus for his own pleasure outside of class work. He did, in fact, a great deal of collateral reading for many of his courses. He seems to have taken all of his freshman courses in easy stride—except mathematics. The first study within this science was algebra, using as text the Collegiate Algebra of Elihu T. Quimby, Dartmouth 1851, Despite Professor Quimby's connection with the College, as both alumnus and former faculty member, he was hardly the favorite author of the men of '85. "Quimby's Algebra," Hovey vowed, "is the most concentrated essence of pure concatenated, complex double-back-action patent oath-compelling cussedness I ever struck."

That he was not alone in his bewilderment over the algebraic mysteries is attested by the reported sorrow of a classmate at receiving from the publisher the following note:

DEAR SIR- We don't send keys of this Algebra to students of Dartmouth College.

Algebra was followed by geometry and plane and spherical trigonometry, each presenting new and blacker discouragement, but each in turn was mastered to greater or less degree and thankfully put behind as the next was approached.

Finally, June rolled 'round and the class was freed at last from the humiliating status of freshmen and elevated to that height of grandiose pomposity that is known only to the new-made sophomore. With "serene and. unconscious self-conceit" the sixty-odd members of '85 went forth with "sophomoric pride" on their first summer recess to impress family and friends with their newly acquired graces and knowledge.

Come fall, "a minute segment of the class made its appearance punctually" in Hanover, and the rest were there "before much more than a month had passed." But what a different looking group they were! The marvelous properties and diligent application of "Ayer's Hair Vigor" and other similar elixirs seem to have been responsible for no small number of mustachios, Vandykes, and flowing full beards. Hovey reports that he himself had "obtained so much experience in the various good and bad qualities of all those compounds designed to produce crinigerous results upon the adolescent face" that a Pennsylvania medical college had voted him the degree of "B.D. (Barbarum Doctor)."

For the sophoriiore year Hovey was class historian, and from his most engaging chronicle, Hanover by Gaslight; or WaysThat Are Dark, we have a good account of the class during 1882-83.

Concerning the traditional responsibility of the second-year class with regard to freshmen, he recalls that they "assumed with great reluctance the unsavory task of regulating their manners and morals. Strange to say," he adds, "the Freshmen did not appreciate this condescension on our part to labor for their good and refused to submit to our control." The class, however, was conscious of its "duty to society," and as a result of several "rushes" and other individual tutoring, finally brought the new arrivals, to a realization of "the thusness of the this."

Beginning with the second semester of his freshman year and through all of the two years following, Hovey was on the staff of The Dartmouth. Although the class song is his only identifiable contribution to the magazine as a freshman, as a sophomore he wrote prodigiously, and hardly an issue is without one or more of his poems. A few of these were about nature, but mostly he wrote of love. Within the later theme, however, there is present a great variety of treatment. Constancy, for example, is considered from quite different viewpoints in poems for two successive issues of the magazine. On November 24, 1882, he wrote:

The red rose withers and the lily pales; But I will love thee until dawn grows noon,

Till the noon darkens into the last night, Until the stars die and the sun's light fails, while in only the previous number he had penned:

The rose is as sweet as the lily, The violet as sweet as the roseAll flowers are sweet, and 'twere silly To overlook any that blows.

In poetry, Hovey most admired four men: Catullus, Shelley, Swinburne, and Poe. These he considered to be the "impassioned and lyric" poets, and their influence, especially that of Swinburne, is strikingly evident in much of his undergraduate verse.

In February of the sophomore year there took place what was for Hovey and his classmates doubtless the most exciting episode of their college days: the famous "serenade."

A member of the class, "an inoffensive, quiet, hard-working man," had of necessity been absent from College for some time, and upon his return he was required to make up certain recitations to John King Lord, then Associate Professor of Latin. It was claimed that Professor Lord "not only inflicted on him an examination far longer and more severe than those which other members of the class in like position were given, but actually told him that he was an ignoramus." In protest of this supposed maltreatment, in the middle of a bitter cold night about two-thirds of the class gathered together and made their way down College Street to the Lord residence. They were, Hovey writes:

Armed with tin horns, tin pans, conch shells And vast capacity for yells

One moment all was still as death Save for the night-winds fitful breath. One moment more and the frosty air Was rent with an ear-piercing blare.

The good professor sank down into his bed, "and pulled the blankets o'er his head."

Bat when they battered in his door, He could not stand it any more And, quickly pulling on his clothes. He sallied forth against his foes.

And Johnny was enraged to see That they were swifter far than he. But there was one not quite so fleet Because he had such ponderous feet,

He turned aside and sprang into A snow-drift near and waded through. And Johnny followed—by good luck— And in the snow-drift fast he stuck. He struggled till his face was black But 'twas no use—alack! alack! All efforts seemed to be in vain Till after many a writhe and strain, Something gave way and out he scrambled But scarce one footstep had he ambled Ere it was forced upon his mind That he had left his boot behind.

Such were the events of the evening, but while the "horning" of this same professor during the freshman year had ended in joyous choruses of "Bye, baby, bye O!" the present nocturnal concert was a wholly different affair, and Professor Lord was now by no means in any humor for a taffy-pull. In addition to the personal indignities which he suffered, the students "slightly damaged" his fence, and his gate was unhinged and hung in a tree.

For some reason, at which we are left to guess, Richard Hovey "had the doubtful honor of being the first of the class to be summoned before the assembled wisdom" of the faculty as they began their investigation to determine who the participants had been. Actually, as Hovey later admitted to his father, he had not been present at the "horning" at all; adding to his admission, "although I am sorry that I was not."

All might have taken on a lighter hue had not, in the midst of the inquiry, "some person or persons unknown" covered the faculty's seats in the Chapel with a coating of grease.

The faculty now determined to call up each member of the class and offer the alternative, "Either you will tell where you were during the horning or you will be indefinitely suspended." Having previously agreed to stand together, the class, after one or two had been suspended, marched to the faculty room "in a feverish anxiety" for like treatment. And, in deference to their wishes, President Bartlett did, indeed, suspend the class as a body.

A several-day cooling-off period judiciously instituted by the faculty weakened the resolution of a number of the sophomores, and soon everything was confessed. "The class all broke down" as the President put it.

This proved decidedly obnoxious to about twenty men, who immediately declared their intentions to leave Dartmouth. Hovey was outspokenly within this group. He was "enraged with the faculty" and despised the majority of his classmates. After considering a number of other colleges, he finally decided on transferring his studies to Johns Hopkins the following year.

But little by little, as Commencement drew near, "the malcontents began to weaken and retract their positive declarations." Finally, Richard himself, possibly in response to paternal persuasion from General Hovey, joined the others in their conclusion "to forget and forgive and return to their first and only alma mater." The following fall, as '85 entered the junior year, their number was decreased by the departure of only about half a dozen men owing to the episode of the "serenade."

As a junior, Hovey evidently wrote a great deal, although he published fewer signed poems in The Dartmouth than in previous years. In addition to his poetry, he was "maturing" a novel and some short stories, and a part of his time was devoted to his duties as an editor of the Aegis. Not only did he write for this publication, he served also as an illustrator, designing the coyer and furnishing a number of drawings for its pages.

Wilder Dwight Quint '87 in a 1905 number of The Dartmouth Magazine records his undergraduate friendship with the poet, giving a description of Hovey as he appeared in 1883. Quint, in rather reverential terms, recalls the "sturdy figure and that dark and handsome face"; "the great liquid eyes, the black, curling beard"; "the magnificent leonine head set on shoulders in the manner of a piece of classic statuary."

When first they met, Quint writes, Hovey "wore a dark-blue flannel shirt, fastened at the neck with a great, black bow." His "head and face were set off by a grey felt hat with a flaring bandit-like brim. Tweed trousers were tucked into long riding boots, immaculately polished." Quint characterizes him as "eccentric, bizarre perhaps," but "by far the most essentially poetic and fascinating personality that ever dreamed away the spring-time under the old trees."

"There were those who believed him mildly insane; sage townsmen, from behind the safe ramparts of their prosaic counters, would tap their foreheads after he had left their stores with a jest they could not understand.. . Later, they "were, to a man, proud of their acquaintance with 'Sir Richard.' "

"His talk," writes Quint, "whether careless or formal, was of the sort that no man in College could approach. His knowledge of the poems of all ages and languages was colossal, and his fugitive prose work, such as the required essays or the Old Chapel 'rhetoricals,' were filled with flashing gems of beauty in settings of profound appreciation for the best in literature."

One of the old Dartmouth customs which the passage of time has obscured, but which was flourishing in Hovey's day, was the election within each third-year class of four men to "Junior Honors." This was a spirited and ceremonious burlesque in which were bestowed the estimable titles "Knife," "Spoon," "Spurs," and "Spade."

To Richard Hovey in his junior year fell the designation "Spurs" in recognition of his superlative proficiency as a "pony rider"—"pony" being, of course, the col- loquial term for an English translation of the Latin or Greek texts used at the time. Samuel H. Hudson substantiates his class- mate's just claim to this distinction in his

"Chronicles" of the Class of '85. StatingS that "the supreme cheek of Richard Hovey was always amusing," he recalls the time Dick "told Professor R. B. Richardson that he couldn't read the Greek as he only had the text with him."

In the fall of 1884, Hovey entered his senior year. Late October found him writ- ing home the startling news: "Your hope- ful offspring is a member of the Dart- mouth College Cleveland and Hendricks Club and is pleased to tell you that he was offered the presidency of that influential political body but declined with thanks." -» r TT _ -«.. l tlllt IIOV

Mrs. Hovey couldn't believe that her son was "in earnest in this political move." She liked not at all the sound of his pro- posals "to buy votes right and left" and forthwith sent him "a strong letter" on the subject. In a ten-page reply, Dick made it perfectly clear that he was very much in earnest in supporting the Democratic standard-bearers. "The Republican party," he reasoned, "is of an honest parentage. There have been no grander men in the political history of the country than Lin- coln, Stevens, Chase and Sumner. But it does not follow that James- G, Blaine and Steve Elkins are therefore grand and good or anything but mean and despicable."

"It seems to me," he said, lashing out at Blaine, "that the Republican party has nominated the champion demagogue of these United States." Cleveland, he declared, was "a monomaniac" concerning "honesty of government."

Unfortunately, we have no record of Hovey's reaction to the victory of his candidate in the November elections; the first Democratic victory in 24 years. It is too much to expect, however, that in one or two of his subsequent letters he did not enjoy the outcome somewhat at the ex- pense of his Blaineite parents.

Besides his literary pursuits, Hovey had an active interest in oratory, and on several occasions proved himself a capable practitioner of that art. In both his senior and junior years he won top honors in dramatic speaking at the annual commencement contests.

He himself tells of an amusing incident concerning a preliminary competition held in the Chapel in late winter, 1884, to select contestants for the prize speaking the following June. On this occasion Hovey was a participant, and in order to eliminate the anxiety of waiting for the decision of the judges to be announced, two freshmen were hidden in the chapel organ. There they remained when everyone save the committee had withdrawn and were the unsuspected auditors of the deliberations; afterwards reporting to Hovey that he had been given second place, which assured him a chance at the prizes later on.

Commencement time in 1885 was a period of even more than usual ceremony and excitement. Festivities began well over a week in advance of the graduation exercises. There was the annual senior "SingOut," open air band concerts by the Dartmouth and Boston Cadet Bands, and the oratorical contests in the college church. An affair of great solemnity and ritual was the dedication of the senior class's tree. On the evening of June 17, the entire student body formed in front of Dartmouth Hall and marched, to the accompaniment of a brass band, to the spot in the College Park where a marble block marked '85's elm. The tree was "wet down" with lemonade, and yells were raised in praise of the class.

It is to Hovey's class that the credit belongs for beginning the erection of what has become one of the College's most prominent and interesting landmarks. The men of '85 laid the foundation for Bartlett Tower, and on Class Day put in place the first memorial stone, above which may now be seen the several class markers at various heights commemorating subsequent annual additions to the tower.

Whereas Bartlett Tower was just being started in June 1885, two buildings on campus had just been completed and were ready for use. The day before Commencement was the occasion of ceremonies dedicating both Rollins Chapel and Wilson Hall.

Thursday, June 35, was Commencement Day, and Richard Hovey had a prominent part in the exercises, delivering a noteworthy dissertation on Victor Hugo. His abilities as a student won him final honors in English, his degree cum laude, and election to the Phi Beta Kappa Society. Not only did he lead his class in English, he earned honors in history and was commended for his mastery of Greek.

Yet however impressive Hovey's general scholastic accomplishments may have been, it was not his scholarship that won him the respect of his associates. Many students and faculty members alike seem to have clearly recognized his ability and promise as a poet, and it was for this that he was most highly esteemed.

Indeed, it appears that the faculty was proudly aware that in graduating Richard Hovey, Dartmouth was at last sending forth a poet. President Tucker, writing of Hovey years later, expressed the basis for at least part of this sense of proud concern. "No training," he said, "can ensure the poet. We can only wait his coming."

What Richard Hovey's coming has meant to Dartmouth requires no documentation. His contribution has been great and has won him his rightful place among the College's most famous sons.

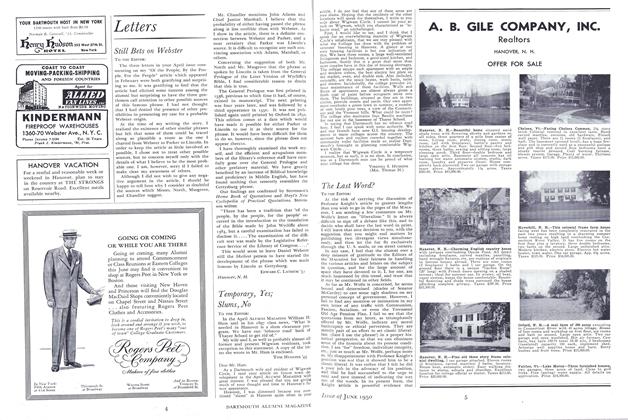

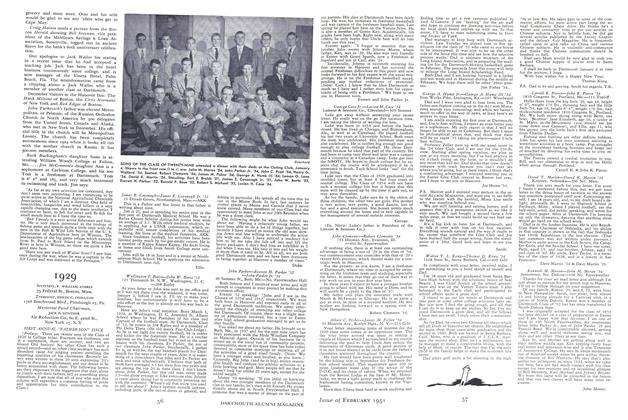

THEY ALL CAME BACK: A contingent of 1885, all ready to go, photographed at the time they were suspended for "horning'' Prof. John King Lord. Hovey, also suspended, is not in the picture.

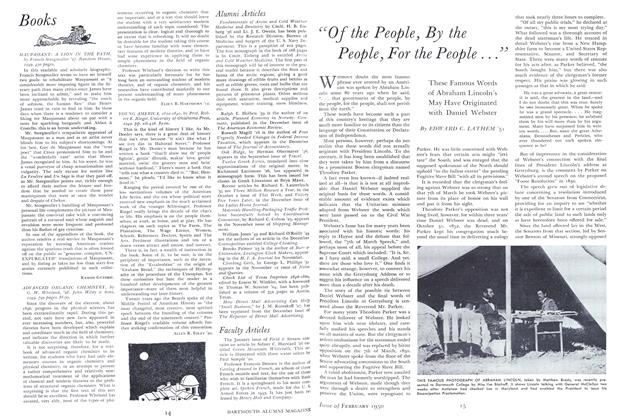

HOVEY AS A JUNIOR

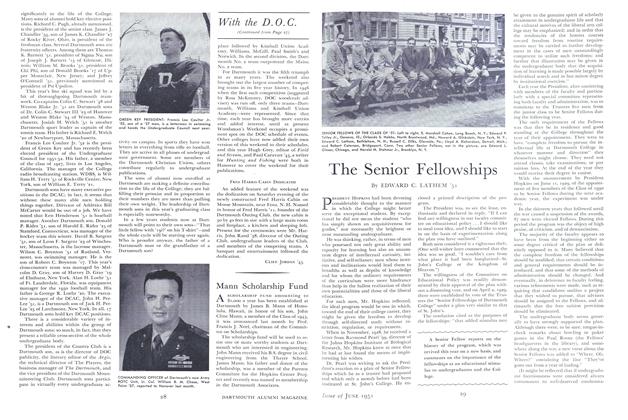

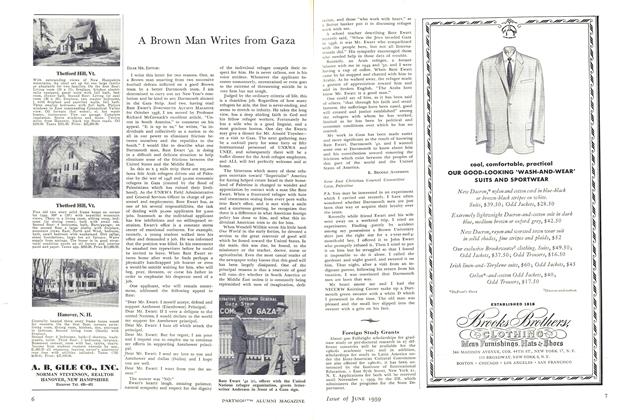

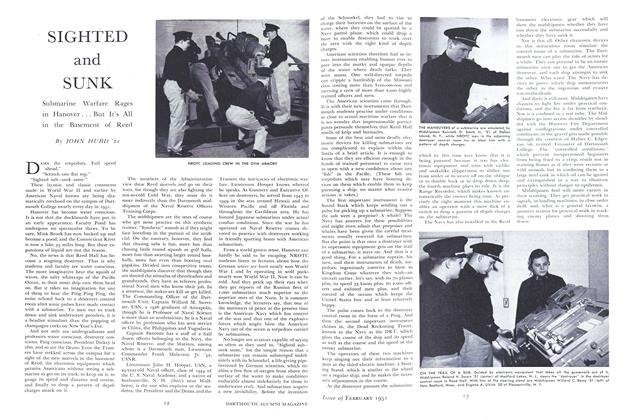

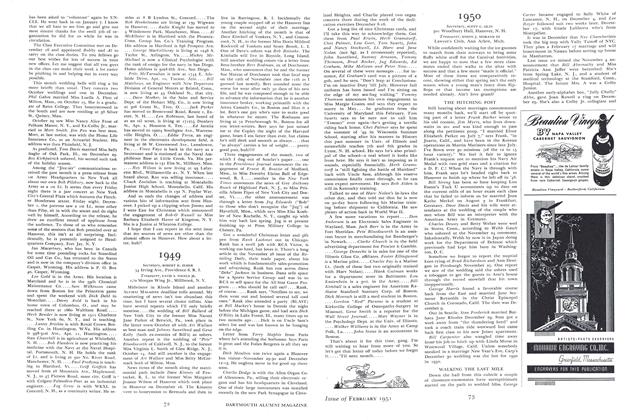

GRADUATION POSE: The Class of 1885, about to become alumni, gathers on the steps of Wilson Hall, dedicated that year as the new library. Hovey, a class leader, is second from the left in the front row.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

February 1951 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, EDWIN C. CHINLUND, JACK D. GUNTHER -

Article

ArticleSIGHTED and SUNK

February 1951 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

February 1951 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, DAVID L. GARRATT -

Class Notes

Class Notes1933

February 1951 By GEORGE F. THERIAULT, LEE W. ECKELS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1905

February 1951 By GEORGE W. PUTNAM, GILBERT H. FALL -

Class Notes

Class Notes1950

February 1951 By SCOTT C. OLIN, SIMON J. MORAND III