Liberal Arts Education, Buttressed by Public Support And Understanding, Is the Free World's Best Hope

JOSEPH STALIN in his most recent "interview" admits that the American and British generals are "not worse than the Chinese and Korean ones" but, he continues: "It stands to reason that the most experienced generals and officers can suffer defeat if the soldiers regard the war imposed upon them as unjust and if, as a result of this, they perform their duties on the front in a formal way without faith in the righteousness of their mission and without enthusiasm."

These are golden words in a world becoming daily less familiar with gold. The Second World War proved the soundness of this latest Kremlin decretal. American men sent out from the liberal arts colleges fought with rather surprising success—at times even under not too experienced leaders. Ergo, according to the pronunciamento from Moscow, they must have been imbued with enthusiasm and with faith in the righteousness of their cause. The colleges did more for them than that. They taught them also how to keep up their mental and emotional strength in combat and to return sane, to a degree that amazed psychiatrists.

The liberal arts college is one of the greatest bulwarks of the free world against communist slavery. Those wise men in the Politburo know this. Skilled beyond any Greek sophists in making the worse appear the better reason, they fear the product of an institution which has no objective other than to preach the truth. Doubtless if the Russians had the time they would consider it more profitable to destroy our colleges than to bomb our atomic installations.

That brings up the question: Do we Americans value our liberal arts education as highly as we should at a crisis such as the present, or are we, on the approach of war, prone to wish that we had steered our young men into the assembly lines of vocational training? A recent magazine poll seems to support the latter assumption.

In September of 1949, Fortune published a "Survey on Higher Education." The tabulated returns indicate that citizens of every rank are enthusiastic about the colleges and willing to pay the cost. But when it comes to what the people want from the colleges the picture is not so satisfactory. For example, the questionnaire shows that "a better appreciation of such things as literature, art, and music" is designated as the least important college aim for boys! Training for a particular occupation or profession is overwhelmingly voted the most important (shades of Wheelock, Tucker, and Hopkins!). The editors of Fortune were flabbergasted at this emphasis on the strictly utilitarian, for the percentage of college alumni which made this choice was only slightly less than the percentage of those who had experienced no schooling beyond the secondary grade.

The Advisory Committee of the above poll was headed by Frank W. Abrams, Chairman of the Board of the Standard Oil Company of New Jersey,—a man well known to educators for his interest in the liberalization, by statute or judicial interpretation, of the common-law rule which contends that a corporation must reasonably expect to benefit in a direct way from its gifts to education. He commented with concern on the public's conviction that the value of higher education is to enable one to get a good job or to enhance earning power. That is all right for the law, engineering, and medicine, he admitted, "but the report indicates to me too conclusive an emphasis on this aspect of the subject. . . .

The primary purpose of higher education, it seems to me, is to turn out people who can apply reason to any situation (not just job situations), who have wide interests, who are self-disciplined, who have rudiments of at least a satisfactory personal philosophy, and can find satisfaction in many things beyond the purely material." This gratifying definition from an outstanding man of business was echoed by the professional educators on the Advisory Council. President Baxter of Williams reported to the same tenor: "It also shows that we have a long way to go yet in selling to the public the notion that education leads to a good life in place of the view that it leads to a success story."

This conflict between liberal and vocational training is not new in American education. Indeed, the movement to make liberal training more utilitarian started over a century ago. The result has been, says the editor of School and Society glumly, the proliferation of courses, and the development of specious arguments,—that liberal education is vocational and vocational training can be liberal—to the detriment of both. Before anyone attempts to sell to parent or student the liberal arts college he' should get a fairly concrete conception of how liberal education differs from vocational or professional preparation.

LIBERAL education, etymologically speaking, is the education of the free man (liber), in a society predicated on slavery or an inferior class, where manual labor and menial tasks were not the concern of the free man—as, for example, in Greece or Rome. This Greco-Roman education was the education of the ruling class. The arts and sciences which taught man how to rule were the substance of the curriculum. If one wanted to learn the practical art of engineering, he attended no school-there was no such school for him to attend. He apprenticed himself to an engineer who had already arrived. James Loeb, the distinguished Franco-American banker and scholar, favored this system. He was said to have expressed regret, after his graduation from Harvard, that he had "wasted" the greater part of his last semester on courses in banking (professional) which he might have devoted with greater profit to the useless classics (liberal), and have acquired skill in finance during his business apprenticeship.

Liberal education, then, is not training for banking, or manufacturing, or cotton growing. In a polity consisting of rulers and the ruled, liberal education is the prerogative of the former, the best (cf. aristocracy, rule by the best). This schooling was not, however, for an aristocracy in our sense of the word; but, unfortunately, many still look upon the liberal arts training as aristocratic or snobbish. Actually, it was merely the right discipline for whoever was to rule.

If we apply this conception of liberal education to the United States, who are the rulers, and who, being rulers, must have this education? Former Chancellor Hutchins of Chicago; in a speech last year, answered this question rather persuasively. Our democracy is based on universal suffrage. Universal suffrage makes every citizen a ruler. This is the crux of the matter. If liberal education is the education of the rulers, then every American must have a liberal education.

This may sound like a counsel of perfection, and it is, as we look at the actual world about us; but upon it rests to a large extent the justification of the liberal arts college. We have only theoretically attained to universal suffrage or universal education, but we are on our way. Added leisure, as the hours of the laborer are shortened, means more free time for the cultivation of the mind. The working man cannot devote all his off hours to golf, yachting, or riding to hounds. What was formerly the intellectual property of a small ruling class will be, in our American future, the property of all who are capable of absorbing it. "To attack liberal education as aristocratic is to mistake its origin for its content."

According to our critics, America is cutting a sorry figure as leader of the world. Is Washington to blame? If so, who tied the hands of Washington? None other than these rulers of the United States, the people. You can't speed every boy back from war and into the bosom of his family, reduce taxes, and, at the same time, keep the forces armed to the teeth against Russia. Even Tom Dewey could not have accom plished that result. Vocational training does not help us here, for vocationally we have outstripped the world. Our only salvation lies in more and better liberal edu cation, the education of the rulers. Today in America even more than in ancient Greece, Plato's well-worn words in TheRepublic are germane: "Until philosophers are kings, or the kings and princes of this world have the spirit and power of philosophy, and political greatness and wisdom meet in one, and those commoner natures who pursue either to the exclusion of the other are compelled to stand aside, cities will never rest from their evils, no. nor the human race." Plato, contemplating the ruin which the Peloponnesian war had brought upon the Hellenic world, put all his faith in education of the rulers of his ideal state. Likewise we, facing a far worse cataclysm, can survive not alone by skill of hand or machine, but through the wisdom of our rulers, the people.

Therefore the liberal college is not a "combination of sanitarium, dancing class, and reformatory"; it is not a means of keeping young men off the streets and out of the labor market; above all, it is not a hippodrome for the mad pursuit of material well-being. It is a haven where one may devote himself to the study of ideas, may go beyond the gaining of knowledge and skills to the acquisition of wisdom and the molding of character, and may form convictions about mankind, the world, and the basis of right conduct. If democratic society is to survive and if our western civilization is not to become the Frankenstein's monster of modern education, which from its very technical skill may yet destroy the world, the influence of the liberal arts college will have to be increased many fold. The long hard path toward learning how to rule intelligently and how to live nobly does not lead through the vocational college or the professional school. The good life and the success story are not mutually exclusive; but the first is the product of liberal studies and the second of vocational training, whatever their chance chronological relations.

THE CONTENT of the liberal curriculum has always been a subject for vigorous discussion, even so far back as the year 1765, when Harvard candidates for the Master of Arts degree were still writing theses on such topics as: Did Adam Have anUmbilical Cord? But at no time has the interest been so widespread as since the First World War. That conflict showed that the candidates for officer commissions knew little about the democracy for which they were being trained to fight. A course entitled War Aims was introduced into the curriculum of the Students Army Training Corps to supply this deficiency. It was ambitious; it traced the development of our civilization from the first faint signs of life in the slime on the bottom of some primordial sea to the year of grace 1917!

Columbia College, immediately following the war, introduced a required curriculum which grew out of the experience with War Aims. It postulated a rigid prescription, for the first two college years, in the three divisions: the humanities; the political and social sciences; and, with less strict prescription, the physical and biological sciences. Since then many schools have followed suit, especially under the impact ol the Second World War. The discussion of education for intelligent citizenship and the good life has been continued under the title of general education, a current term loosely applied to liberal education in the first two years of college.

According to the Fortune survey mentioned above, not all college graduates could define the purpose of a college education; yet books on this subject are legion and easy of access in popular form. To cite a few: Mark Van Doren, Liberal Education; Jacques Barzun, Teacher in America;Liberal Education Re-examined: Its Rolein a Democracy, a study sponsored by the American Council of Learned Societies; General Education in a Free Society by the Harvard $60,000 committee; and The Ideaand Practice of General Education by the University of Chicago Faculty. These are typical and very readable accounts for busy alumni desirous of enlightening themselves and college prospects on the objectives of the liberal college. Naturally alumni will grumble: "Dartmouth never did those things for me." Of course it did not. No man ever believes, as Van Doren complains, that the right things were done to his mind. He was forced to learn too many facts, or too few; the teaching was too general and nebulous, or too special and meticulous; the present was ignored, or the past; he was not forced to take the proper courses, or there was too much prescription. However, the books suggested above will outline the aims of liberal education, even if they are not always achieved.

The courses of the current liberal curriculum for the first two years are assigned to three divisions or fields, and with each of these divisions every student must have an irreducible minimum of acquaintancesuch is the theory. The prescription may be à la carte as at Dartmouth, or table d'hote as at Columbia. The last two years are devoted to further elective courses and the major, or to completing the preparation for a professional school.

The sciences teach him the nature of the world, which conditions human living; he cannot be a useful citizen today if his knowledge of the significance of aeronautics does not surpass that of Leonardo da Vinci. The social studies orient him with respect to his social environment and human institutions, local, state, national, and world-wide. No American can analyze our present sorry universe who has not had a modicum of schooling in the social sciences. The aim of the humanities is to enable man to understand man in relation to himself, to distinguish between himself as man and as individual, to become one in imagination with the great doers and thinkers, writers, artists, and poets. Such in brief is the content of liberal education. The student who has been exposed to it, if he has been inspiringly taught and if he has studied with mutual devotion, will far surpass as citizen, as social being, and as individual, the man with only technical training.

In answer to a demand from a Dartmouth graduate, at an alumni meeting early in the last war, that the College should offer more courses of a practical nature, a Dartmouth engineer, busied in letting government contracts to the tune of millions daily, replied quietly that he could get adequately trained technical engineers at a dime a dozen; what he needed in his office were engineers with imagination, and these he found among men who had pref- aced their technical schooling with courses such as Dartmouth offers. The graduate, if he has not neglected the main tent for the side shows, should, on leaving campus, have cultivated his imagination, learned how to think effectively, be able to communicate his thought, to make relevant judgments, to discriminate among values, to reach decisions warranted by given situations, to improvise in emergencies, and to develop in himself the whole man. This is the type for which the practical world searches far and wide. Business men will be willing to assist the colleges which produce such alumni when once they are convinced that their aid is necessary.

IF enough has been said to hint that the liberal arts college is indispensable, what is the justification of the privately endowed liberal arts college? It can't be based on superiority. Citizens of Michigan, North Carolina, or California would smile at such a claim, or feel resentful. The justification of the private college is rooted in our tradition of educational diversity. In general, the private institutions were founded first, and were well established before the great state and city colleges came into existence. And as George N. Shuster, president of a large city college, expresses it: "Public education in this country has profited greatly by reason of the freedom and diversity of the private schools; and these in turn would be incredibly stupid if they failed to appreciate the bustling virility and liberal outlook of the public institutions." Both profit, reciprocally, as Shuster suggests. Indeed, the case for the private and the public school is exactly parallel with the case for private and public business,—each is a complement of the other. We need private capital at work in the New England Electric System, and we need the government activities engaged in the Tennessee Valley Authority; neither would be so progressive or so efficient without the other. And so it is with the public and private college.

This line of vindication is making a strong appeal to business men. Henry Ford 11, in Let's Keep Education Competitive (1948), an address to his fellow alumni of Yale, earnestly supported this view. His thesis was that there is no substitute for competition in the field of education. "I believe very strongly that the existence of a large number of vigorous, dynamic, privately endowed colleges and universities is the best possible insurance that our whole higher educational system will be first rate." Mr. Ford considers the relation of state and private schools parallel to the relation between state and private capital. Noting that the contributions of corporations to philanthropy are today nine times what they were ten years ago, he adds: "This is another evidence of the recognition on the part of corporations that they have a social responsibility and a contribution to make beyond the manufacture of better products at lower costs. Perhaps we will see an increasing contribution to education on the part of other modern institutions the labor unions, for example." Mr. Ford is optimistic (by the way, he pays the traditional tribute to the Dartmouth Alumni Fund), but he is also realistic; he ends on the key on which his address began: the responsibility for getting out the funds rests on each alumnus personally.

If then the private liberal arts college has justified itself, how can it be saved? The alma mater of every one of us who attended a privately supported college points her finger at her son and says: "Thou art the man!" The days have almost passed when an oil baron could contribute $34,708,375 to a university in the Middle West, or a tobacco king an even greater sum to its counterpart in the South. The multiplicity of those fabulous fortunes which aided colleges is no more; the income tax and, if the decedent has let nature take her way, the inheritance tax have seen to that. Colleges can no longer count upon a few munificent patrons to build their buildings and to balance their budgets. Time was when the president and, more frequently, the trustees through personal contacts were able to secure all necessary financial assistance. Indeed until the quite recent past, this had been the pattern for the private college.

What under present circumstances will be the pattern for the future? Simply this: each alumnus, over and above his own personal contributions, must be willing to assume a responsibility which formerly rested upon the shoulders of president and trustees; from now on he is the one who must be watchful to discover and adroit to exploit opportunities for securing donations from all possible sources. Though huge fortunes are vanishing, certainly the American world has not become impoverished. What were before vast resources in the hands of the few have become even vaster resources in the hands of the many. From these must come the ways and means; many donors of modest competence must be approached by many agents. And the only available agents in sufficient numbers are the alumni. As President Cole of Amherst says of the immediate prospect: "Alumni loyalty alone can preserve the freedom of American education."

Is there money to be had for our purposes? The answer is an emphatic "Yes, so soon as alumni have enlightened the public on the financial needs of the independent college." The sum of $73,000,000 was contributed to seven Ivy group colleges during 1946-1948. Harvard, for the fiscal year ending in June 1950, reported capital gifts of $18,555,110; and for current use gifts of $7,387,377; government research contracts, a field not open to the undergraduate teaching liberal arts college, totaled $2,411,631 more; and, in addition, some special government grants approximating $250,000 swelled the Cambridge budget. Princeton, in a quiet year, collected in gifts and legacies $3,613,868; Bowdoin and Williams, of about 1,000 registration each, $1,477,000 and $882,887 respectively So, there's gold in those hills if enough prospecting is done.

The soaring cost of running a college and the falling income from endowments make prospecting necessary. The general public still has to be trained in giving aid to private higher education, a really new philanthropy, on the scale on which it contributes to hospitals or community chestsevery contributor in accord with his means and the contributions repeated year after year. This task of enlightenment only the many alumni can accomplish. The community chest did not spring full-fledged from the brain of some community father; it was the result of thoughtful propaganda and hard labor on the part of the many who saw in this device a logical way to get more contributions and to get them more regularly. So it will be in the future in respect to the support of the private college.

And the funds, make no mistake, will be secured only when all alumni throughout the nation take an active part in expounding to the public the role of the private college and its present needs. For a thoroughly informed people is a prime necessity for any fund-raising campaign. Not only Dartmouth as in jeopardy, but every private college and university; and that means that the fruitful diversity of our educational system is imperiled. Sell the general cause first, the private liberal college. For, as the bible of experienced fund-raisers says: "The cause must be bigger than the institution. Sell ideas—don't just ask for money." Then turn to the specific, the individual college, to wit Dartmouth, and point to its services to the nation. All that is needed is the active participation of every alumnus. The colleges of America have issued a plea for help. In the crisis, no alumnus can fail to strengthen one of the indispensable foundations of the free world.

ROBERT FROST '96 DISCUSSES POETRY AND LIFE WITH DARTMOUTH UNDERGRADUATES

THE SCIENCES, an essential part of liberal arts education, join with the humanities and the social sciences to produce rounded, intelligent citizens.

AN INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS SEMINAR, TAUGHT BY PROFESSOR JOHN PELENYI

DANIEL WEBSTER PROFESSOR OF THE LATIN LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE

The Author: William Stuart Messer, in addition to the scholarly talents one would expect of the Daniel Webster Professor of the Latin Language and Literature, possesses a versatility and a capacity for work that have won him a respected place at Dartmouth—and more work. During the last war, when he taught the classics one hour and laboratory physics the next, he was chairman of the American Defense Dartmouth Group, managing chairman of the Committee on Defense Instruction, and chairman of the Special Committee on Academic Adjustments. Formerly on the Educational Policy Committee, he is at present a member of the Faculty Council. Professor Messer's deep interest in the philosophy and practice of liberal education began at Columbia, where he took his bachelor's and doctor's degrees and taught for eight years before coming to Dartmouth in 1919. This article combines his belief in liberal education with a concern for its financial support that was sharpened during his recent service as the first faculty representative on the Dartmouth Development Council.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleDeaths

May 1951 -

Article

ArticleHe Values the Rare In Books and Life

May 1951 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

May 1951 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Article

Article1949

May 1951 By ROBERT H. ZEISER, DAVID S. VOGELS JR., JOHN F. STOCKWELL -

Class Notes

Class Notes1905

May 1951 By GEORGE W. PUTNAM, GILBERT H. FALL, FLETCHER A. HATCH -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

May 1951 By KARL W. KOENIGER, DONALD BROOKS, HOWARD A. STOCKWELL

WILLIAM STUART MESSER

Article

-

Article

ArticleMasthead

November 1923 -

Article

ArticleIn the Key of D

Novembr 1995 -

Article

ArticleHanover's Most Illustrious Woman

November 1937 By GABRIEL FARRELL '11 -

Article

ArticleHOW THE OUTING CLUB "BREEDS BACK" TO PLATO

December, 1922 By JOHN E. JOHNSON -

Article

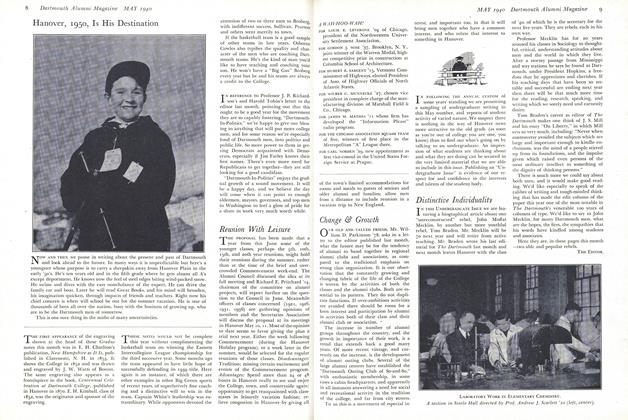

ArticleNotebook

Sept/Oct 2004 By JOHN SHERMAN -

Article

ArticleDistinctive Individuality

May 1940 By The Editor