Raymond of the Times—Selected Poems ofEberhart—Three Studies in Social Science

by FrancisBrown '25. W. W. Norton & Company, 1951;ix + 345 pp., $5.00.

This excellent book, written by the editor of the New York Times Book Review, admirably demonstrates the usefulness of biography in providing a focus for the understanding of history. By following the precocious journalistic and political career of the first editor of The New York Times, the reader is carried along through the years of the Whigs' high hopes and through the period of that party's deliquescence. Raymond played a very considerable part in the social and political history of the United States, not only as the greatest journalist of his day—even in comparison with such giants as James Gordon Bennett and Horace Greeley—but also as a politician who, after holding several important elective posts at Albany, rose to be chairman of the Republican national committee in 1864 and a member of the House of Representatives in the period of reconstruction, during which he stood out as the valiant spokesman for the discredited policy of moderation and reconciliation. For any person, such as your reviewer, likely to be hazy about the mediaeval period of American history—to confuse Taylor and Tyler and be not quite sure whether Pierce or Polk came first—this book will provide enormous enlightenment. Written by a man who obviously possesses a remarkable understanding of the history of American politics and journalism, the biography enables one to realize, among a wealth of other things, what it really meant, what it felt like, to be a Whig in the days of Webster and Clay.

Although a man of considerable intellectual and cultural range, Raymond was not a person given to much introspection or self-revelation and there is a sort of bland impersonality about him which disappoints a reader who seeks in biographies a presentation of the complex interplay of motives and the analysis of loyalties in conflict. Perhaps it was the author's choice to place the emphasis much more on the public career than the private life of Raymond, as seems to be indicated by the fashion in which are treated such topics as the nature of Raymond's religious convictions or his relations with his wife or his philanderings. Yet there can be no question that the author is correct in judging that posterity is more interested in Raymond's impact upon his times than in his inner life. The former was quite substantial enough to justify fully this detailed and—to quote the 'NewYorker—"full-dress" biography, written by a man whose historical scholarship and whose delight in his profession are equally apparent.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE COLLEGE

October 1951 By C.E.W. -

Article

ArticleThe Moral Supports or Education

October 1951 By C.E.W. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

October 1951 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Article

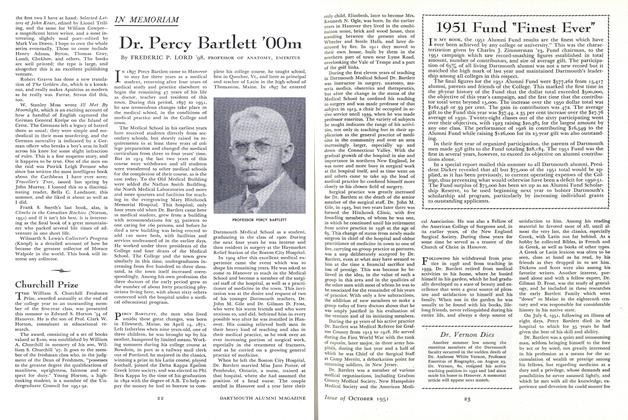

ArticleDr. Percy Bartlett '00m

October 1951 By FREDERIC P. LORD '98 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1950

October 1951 By ENS. SCOTT C. OLIN, USN, SIMON J. MORAND III -

Article

ArticleAssociated School News

October 1951 By Karl Hill

Arthur M. Wilson

-

Article

ArticleDemocratic Thought

December 1941 By ARTHUR M. WILSON -

Article

ArticleThe Role of the Humanities

May 1946 By ARTHUR M. WILSON -

Books

BooksTHE LITERARY ART OF EDWARD GIBBON.

June 1960 By ARTHUR M. WILSON -

Books

BooksHUMAN NATURE AND POLITICAL SYSTEMS.

November 1961 By ARTHUR M. WILSON -

Books

BooksTHOUGHTS FROM ADAM SMITH.

JUNE 1963 By ARTHUR M. WILSON -

Books

BooksMIDDLING NESS:

APRIL 1966 By ARTHUR M. WILSON

Books

-

Books

BooksTHE SOVIET DESIGN FOR A WORLD STATE.

July 1960 By CHARLES B. MCLANE '41 -

Books

BooksRights and Wrongs

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1984 By Charles M. Culver, M.D. -

Books

BooksFrontier Plans and Dreams

May 1980 By James Wright -

Books

BooksSELECTED WRITINGS OF OSCAR WILDE.

JUNE 1969 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksThe Great Chain of Being

APRIL 1984 By S. Marsh Tenney '44 M.D. -

Books

BooksPRINTING AS AN ART.

May 1955 By THOMSON H. LITTLEFIELD '41