Seven Faculty Members Democratize "Our Artistic World"; "Time of Peace" Traces American Thought, 1930-1942

By Artemas Packard, general editor, and Donald E. Cobleigh '25, McQuilkin DeGrange, ChurchillP. Lathrop, Marjory Bowen Lord, HughMorrison '26, and Stearns Morse. Privatelyprinted, 194-, three volumes, paged continuously.

THESE VOLUMES CONSTITUTE part of an important experiment in adult education organized upon a commercial basis. For some thirty years, the Delphian Society of Chicago has organized study groups, called Delphian Chapters, in numerous communities throughout the country. In return for membership fees, the Society has supplied study material. In 1935 Professor Packard was appointed a member of the Society's advisory board, which proceeded to recommend a complete reorganization of the Delphian Society study material. As a result, nine volumes, under the general title of The Individual and the World, have recently been issued from the press. The whole set is designed to provide material for three years of group study and discussion, of which the last year will be devoted to the volumes herein reviewed.

If this, dear reader, sounds to you like one of the stereotyped and conventional short cuts to Culture, guess again. The Delphians are going to make some surprising discoveries. They are going to find out that art is not something which we may casually survey when we please, and turn our backs upon when we choose. They are going to learn that art is not "the manifestation of a world apart, inhabited only by a fortunate few who by some accident of birth or training have been admitted to the magic circle of 'culture.' " What Professor Packard has so lucidly planned and what his colleagues have so loyally carried out is the demonstration that matters cultural have been and can be an integral part of every-day life in every society, from the primitive societies which Professor DeGrange trenchantly describes to the more complex sophistications of our own day.

The curse of almost every, conspectus of this sort is that it manages to make art-forms and the history of art seem esoteric and alien. The authors of these volumes, on the contrary, repudiate all snooty and pseudo-aristo-

cratic theories of art. They make art democratic, by reminding us that we can all develop active and positive canons of taste and do not have to take our aesthetic judgments secondhand. We can participate in art. And that goes for much more than just what comes off an easel. Art includes this, of course, and Professor Lathrop's discussion of painting (and sculpture) is fresh and masterly. No less, of course, it also includes architecture. Professor Morrison's discussion is impregnated with that understanding of what is vital in architecture which one would expect from the distinguished biographer of Louis Sullivan. Art also includes the many forms of literature, of poetry and prose, of drama (including Hollywood!), and the mime and dance. These are urbanely treated by Professor Morse, who clinches with a graceful epigram many a cogent point. Music, likewise, is included; and Professor Cobleigh, who has long proved to Dartmouth glee clubs that he can communicate a knowledge of music by gestures, herein demonstrates that he can do it also by words. Finally, in an extremely effective chapter, Marjory Lord (Mrs. Artemas Packard) discusses the art of dress.

Two things particularly distinguish these volumes: they are written con amore, and they are written with horse sense. I recently heard it said that we call it horse sense because humans so rarely possess it. These authors do. Professor Packard, as chief of staff of this enterprise, in chapters with titles such as "The Meaning of Beauty," "The Arts in a Democratic Culture," and "Culture Goals for the Modern American," discusses the philosophy and metaphysics of art with precisely this saving grace of strong common sense. In the heat of the battle his pages take on sometimes a little of the asperity of the polemist, but we should remember that all these authors, and he most of all, are evangelists of a sort, and that they are inspired by a hot conviction that in matters artistic, as in matters political and theological, every man has a soul to save.

The volumes are adorned with extremely well chosen illustrations, some of them in color. It is to be hoped that these chapters may sometime soon be published in a form available to the general public.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleHanover's First Aid Maestro

December 1942 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth War Directory

December 1942 -

Article

ArticleThe Five Maries

December 1942 By WILLIAM CARROLL HILL -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918*

December 1942 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1935*

December 1942 By JOHN D. GILCHRIST JR., BOBB CHANEY -

Sports

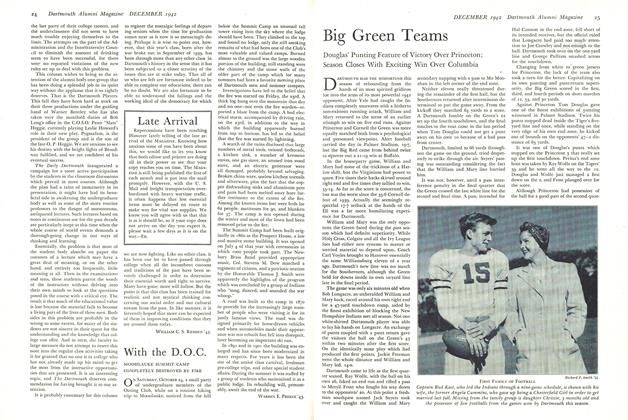

SportsBig Green Teams

December 1942 By Elmer Stevens JR. '43

Arthur M. Wilson

-

Article

ArticleDemocratic Thought

December 1941 By ARTHUR M. WILSON -

Books

BooksLA GUERRE D'UN BLEU.

October 1954 By ARTHUR M. WILSON -

Books

BooksETHICS IN A WORLD OF POWER: THE POLITICAL IDEAS OF FRIEDRICH MEINECKE

MARCH 1959 By ARTHUR M. WILSON -

Books

BooksTHE LITERARY ART OF EDWARD GIBBON.

June 1960 By ARTHUR M. WILSON -

Books

BooksHUMAN NATURE AND POLITICAL SYSTEMS.

November 1961 By ARTHUR M. WILSON -

Books

BooksMIDDLING NESS:

APRIL 1966 By ARTHUR M. WILSON

Books

-

Books

BooksFaculty Publications

December 1948 -

Books

BooksUNOFFICIAL ART IN THE SOVIET UNION.

MARCH 1968 By GEORGE KALBOUSS -

Books

BooksGUARDED BY WOMEN.

MAY 1964 By JEFFREY HART '51 -

Books

BooksSCRAMBLED EGGS SUPER.

May 1953 By Maude D. French -

Books

BooksImages

APRIL • 1985 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Books

BooksTHE AMERICAN WOMAN

June 1944 By Ralph P. Holben