ALEXANDER POPE. ELOISA TO ABELARD WITH THE LETTERS OF HELOISE TO ABELARD IN THE VERSION

MAY 1966 JOHN HURD '21ALEXANDER POPE. ELOISA TO ABELARD WITH THE LETTERS OF HELOISE TO ABELARD IN THE VERSION JOHN HURD '21 MAY 1966

BY JOHN HUGHES (1713).Introduction and Notes by James E. Wellington '48. Coral Gables: University ofMiami Press, 1965. 149 pp. $3.00.

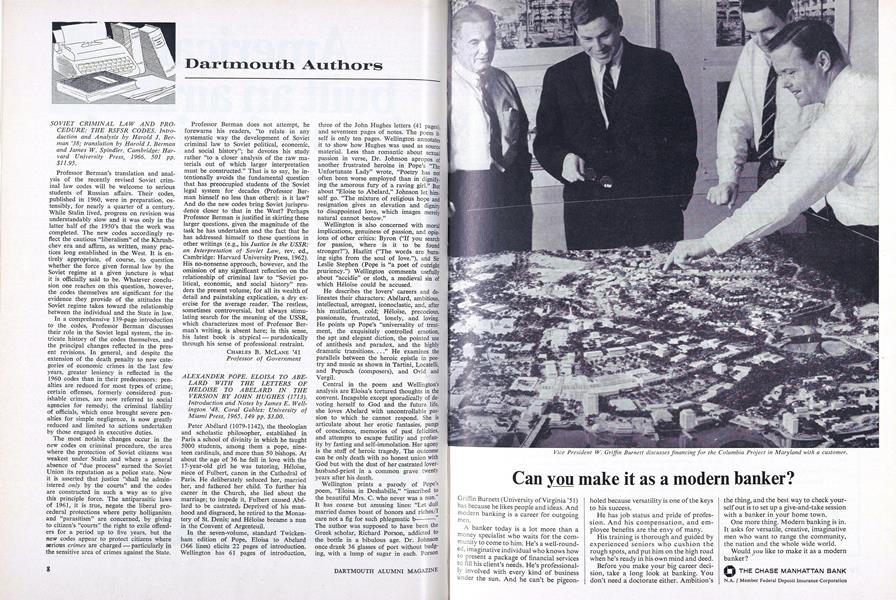

Peter Abelard (1079-1142), the theologian and scholastic philosopher, established in Paris a school of divinity in which he taught 5000 students, among them a pope, nineteen cardinals, and more than 50 bishops. At about the age of 36 he fell in love with the 17-year-old girl he was tutoring, Helo'ise, niece of Fulbert, canon in the Cathedral of Paris. He deliberately seduced her, married her, and fathered her child. To further his career in the Church, she lied about the marriage; to impede it, Fulbert caused Abelard to be castrated. Deprived of his manhood and disgraced, he retired to the Monastery of St. Denis; and Helo'ise became a nun in the Convent of Argenteuil.

In the seven-volume, standard Twickenham edition of Pope, Eloisa to Abelard (366 lines) elicits 22 pages of introduction. Wellington has 61 pages of introduction, three of the John Hughes letters (41 pages) and seventeen pages of notes. The poem itself is only ten pages. Wellington annotates it to show how Hughes was used as source material. Less than romantic about sexual passion in verse, Dr. Johnson apropos of another frustrated heroine in Pope's "The Unfortunate Lady" wrote, "Poetry has not often been worse employed than in dignify, ing the amorous fury of a raving girl." But about "Eloise to Abelard," Johnson let himself go. "The mixture of religious hope and resignation gives an elevation and dignity to disappointed love, which images merely natural cannot bestow."

Wellington is also concerned with moral implications, genuiness of passion, and opinions of other critics: Byron ("If you search for passion, where is it to be found stronger?"), Hazlitt ("The words are burning sighs from the soul of love."), and Sir Leslie Stephen (Pope is "a poet of outright pruriency.") Wellington comments usefully about "accidie" or sloth, a medieval sin of which Héloi'se could be accused.

He describes the lovers' careers and delineates their characters: Abelard, ambitious, intellectual, arrogant, iconoclastic, and, after his mutilation, cold; Heloi'se, precocious, passionate, frustrated, lonely, and loving. He points up Pope's "universality of treatment, the exquisitely controlled emotion, the apt and elegant diction, the pointed use of antithesis and paradox, and the highly dramatic transitions...." He examines the parallels between the heroic epistle in poetry and music as shown in Tartini, Locatelli, and Pepusch (composers), and Ovid and Vergil.

Central in the poem and Wellington's analysis are Eloisa's tortured thoughts in the convent. Incapable except sporadically of devoting herself to God and the future life, she loves Abelard with uncontrollable passion to which he cannot respond. She is articulate about her erotic fantasies, pangs of conscience, memories of past felicities, and attempts to escape futility and profanity by fasting and self-immolation. Her agony is the stuff of heroic tragedy. The outcome can be only death with no honest union with God but with the dust of her castrated lover-husband-priest in a common grave twenty years after his death.

Wellington prints a parody of Pope's poem, "Eloisa in Deshabille," "inscribed to the beautiful Mrs. C. who never was a nun.' It has coarse but amusing lines: "Let dull married dames boast of honors and riches/I care not a fig for such phlegmatic b-." The author was supposed to have been the Greek scholar, Richard Porson, addicted to the bottle in a bibulous age. Dr. Johnson once drank 36 glasses of port without budging, with a lump of sugar in each. Porson used to empty the lees of others' flagons. When the wine ran out, according to rumor, he drank ink. He cared greatly for scholarship.

Professor of English Emeritus

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

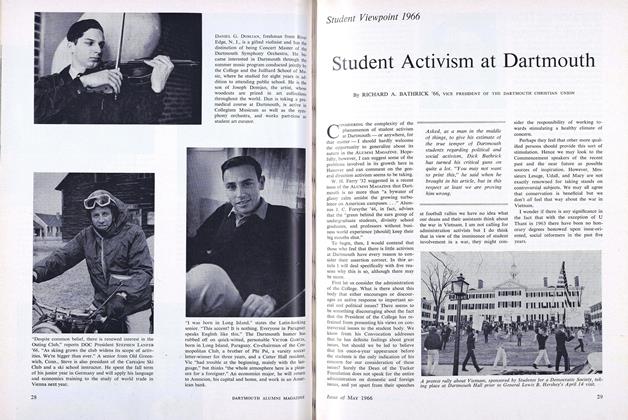

FeatureStudent Activism at Dartmouth

May 1966 By RICHARD A. BATHRICK '66 -

Feature

FeatureThe Rewards Eventually Come in the Upperclass Years

May 1966 By NELSON N. LICHTENSTEIN '66 -

Feature

FeatureANGLOPHILIA HITS THE CAMPUS

May 1966 By ARTHUR N. HAUPT '67 -

Feature

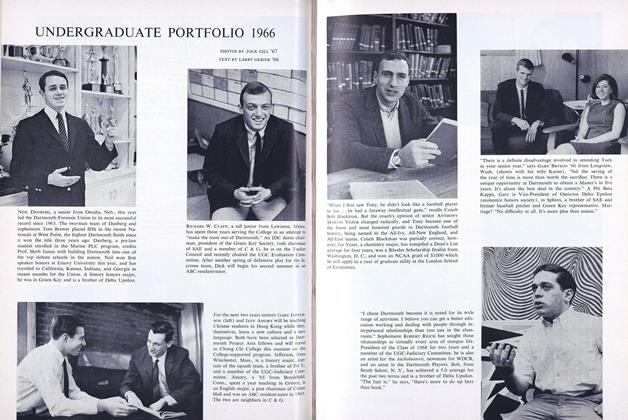

FeatureUNDERGRADUATE PORTFOLIO 1966

May 1966 By TEXT BY LARRY GEIGER '66 -

Article

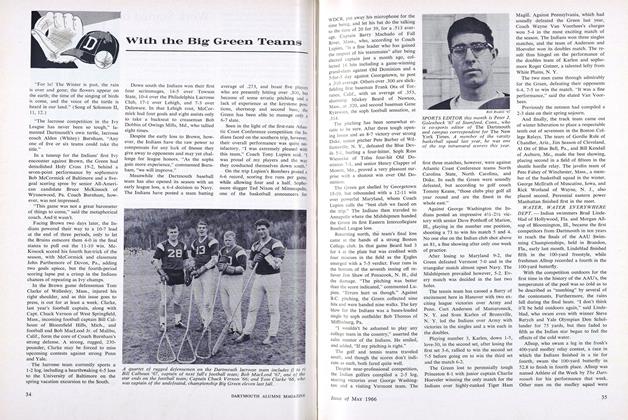

ArticleWith the Big Green Teams

May 1966 -

Article

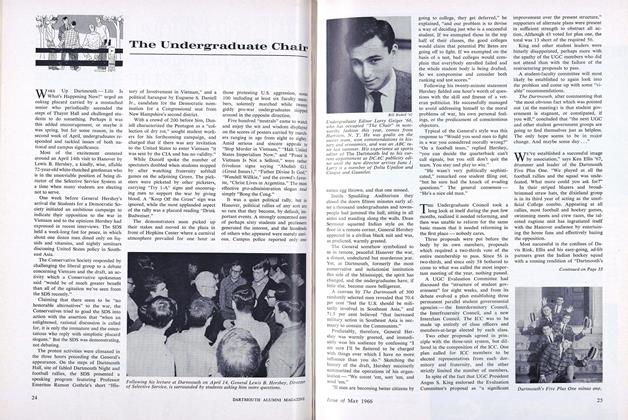

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

May 1966 By LARRY GEIGER '66

JOHN HURD '21

-

Article

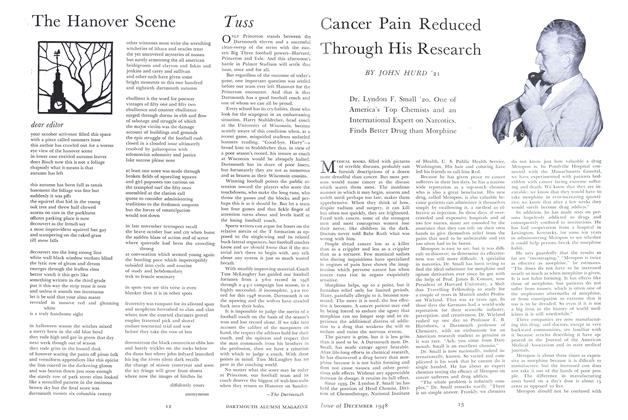

ArticleCancer Pain Reduced Through His Research

December 1948 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Article

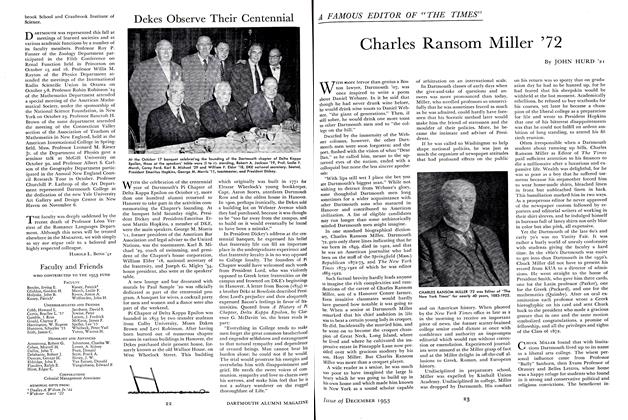

ArticleCharles Ransom Miller '72

December 1953 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksTHE NAKED WARRIORS.

November 1956 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Feature

FeatureDid Webster Really Say It?

JANUARY 1966 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksUNDER THE ROCK, POEMS FROM A VALLEY.

JANUARY 1968 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksROSANJIN: 20th CENTURY MASTER POTTER OF JAPAN.

JUNE 1972 By JOHN HURD '21

Books

-

Books

BooksPETTICOAT FEVER

October 1935 By Benfield Pressey -

Books

BooksTHAT GIRL OF PIERRE'S,

December 1948 By MARGARET BECK MCCALLUM -

Books

BooksBRIGHT SALMON AND BROWN TROUT.

MARCH 1965 By PAUL SAMPLE '20 -

Books

BooksTHE CURRICULUM OF THE COMMON SCHOOL

June 1941 By Ralph A. Burns -

Books

BooksTO THE GOLDEN SHORE. THE LIFE OF ADONIRAM JUDSON.

January 1957 By STEARNS MORSE -

Books

BooksA Barrier of Maple Leaves

February 1976 By WALTER H. MALLORY