Freedom of the Student Press

To THE EDITOR:

A few days ago I was shown a clipping from a Manchester, New Hampshire paper which contained a reprint of an article from TheDartmouth and in addition a photostat of the Dartmouth front page showing the headlines for a silly faultily argued attack on General MacArthur in the worst possible taste and the best Daily Worker style.

Bearing in mind the time when my classmates and I were 22, or thereabouts, and seniors, my rage and disappointment are not especially directed against the editor of TheDartmouth. I do believe that the college administration is badly at fault in permitting this and other effusions. Dartmouth is labelled as a peculiar sort of an institution, unattractive to the fathers and mothers of students of the kind in which we used to say Dartmouth abounded.

Another question arises as to the ownership of Dartmouth College and its traditions. We know, of course, that it is governed by a Board of Trustees, who in turn select administrative officers and there can be little doubt that these men among them are responsible for what the outside world currently thinks of Dartmouth.

I think there is very good reason to believe that these men have failed in their responsibility. Dartmouth really belongs to the great body of the alumni as is demonstrated on various fund-raising occasions. The pride of the alumnus in his college is that institution's irreplaceable asset. Can Dartmouth men take pride in recent news stories which indicate an active sympathy with Russian Communism?

I believe that the fuzzy thinking that calls for presenting "both sides" of that question and which always publicizes the wrong side should be rejected. There will have to be a sharp change in policy before this administration can regain the confidence of many of the alumni.

Cleveland, Ohio

President Dickey's Views

The issue raised by Mr. Wellsted is one concerning which President Dickey has had correspondence during the past month. WithPresident Dickey's permission, we print in fullthe following statement he made on May 9in a letter to an alumnus in New Hampshire.

DEAR MR.

Thank you for your April 27 letter about The Dartmouth and the problem of how much freedom is to be accorded to the press on a college campus.

Let me say to you right off that few things are more trying to the man on this job than living day in and day out with the problems of undergraduate journalism. For every occasion in which someone beyond the campus is annoyed, there are probably fifty occasions when the official College is manhandled with all the zeal of which a certain type of undergraduate mind is capable when confronted with an adult target.

As I am sure you must know, but as I fear many others do not, this is not a new problem either at Dartmouth or on other campuses. Indeed, it is one of the most long-standing problems in undergraduate colleges. There have been many approaches made to its solution none of which, so far as I know, has been entirely satisfactory.

Here at Dartmouth we have had a long tradition of according to undergraduate journalism a freedom which is roughly comparable to the freedom accorded the press in American life generally. There is no need to tell any one who is at all broadly acquainted with American life that we pay a price for this freedom. That price is paid in the irresponsibilities and malice which certain types of individuals practice under the guise of journalism. I am sure there is no need for you and me to be reminded that this price is not confined to college journalism where at least there is the extenuating circumstances of youth to be taken into account.

All colleges do not have a tradition of according such freedom to undergraduate journalism and, believe me, the other tradition often looks wonderfully attractive to the man on this job. Officially and personally, directly and indirectly, he is more often than not the victim on whom the burdens of a free college press come to rest. That press all too often uses him personally as the focus for its criticisms of the College, and at the same time he must bear the consequences of criticism brought down on the College by what that press says about others outside the College. I assure you that it is a position which must be experienced to be understood. Indeed, I am almost prepared to say that no man is entitled to talk about the meaning of the freedom of the press here or elsewhere until he has been a victim of it. Having said that, let me say that on balance I am clear that I would not alter this core principle of American life by one jot. I say that because I believe that to do so would be to take the first firm step toward altering the best in the character of America and thereby really opening the way for enthroning here the errors and evils which we abhor in so many other parts of the world.

If you sense in some measure the nature of the feelings and the conviction which I have attempted to express above, you will understand something of the difficult dilemma which undergraduate journalism presents just as a matter of educational policy. In these institutions of higher education we are constantly seeking at the same time to develop in the same individual the somewhat contradictory qualities of vigorous independent inquiry, responsible thinking and action and, even hopefully, the beginnings of honest humility. Needless to say, there is no pat formula for such a task, and the hard truth about it is that it will at best always be accomplished very imperfectly. Let me see if I can make clear to you how these basic educational objectives of the College bear on the problem of The Dartmouth and, indeed, on the problem of living with any undergraduate paper where there is, as here, a tradition of free expression.

In the first place, the question has got to be asked, Why do we have that tradition and is it worth the cost? The tradition here, of course, goes back way beyond my time either as an official or a student at Dartmouth. Indeed, as you may know, The Dartmouth boasts that it is "The Oldest College Newspaper in America." There are undoubtedly many reasons which went into this tradition, but my understanding of them today places primary emphasis on two considerations: First is the educational value involved in having a community of scholars have its own experience with the raw material of freedom. As each of us knows, it is one thing to read and hear lectures on such subjects and it is quite another to practice and observe at first hand the real thing.

The second reason for this tradition grows out of the practical advisability of limiting the responsibility of the official College as to the irresponsibilities, inaccuracies and immaturities

which are a part of any undergraduate activity. If the College is to supervise and censor the content of an undergraduate paper, it cannot escape total responsibility for what appears in that paper. Parenthetically, let me say that I am fully aware of the fact that we do not today escape being charged in certain quarters with responsibility for everything appearing in The Dartmouth, and I am aware that it can be argued that if we are going to be charged with responsibility we may as well assume it. I am sure, however, that no thoughtful man could be on this job very long- without realizing that the task of supervising and censoring undergraduate journalism involves difficulties and dangers which are at least as great as those which year in and year out we know under the present system. I do want to qualify that to the extent of saying that that seems to me to be inescapably true if one at the same time seeks to preserve the positive educational value which I referred to above as being the primary reason for permitting any kind of undergraduate journalism.

As every student and practitioner of the subject knows, it is almost inevitable that a little censorship leads quickly to more. I once heard an experienced journalist illustrate the point by drawing on the old but vivid adage that "there is no such thing as being a little bit pregnant." I think most observers will tell you that censorship and supervision of the content of undergraduate journalism have the almost inevitable consequence of producing a "tame press." Such a press is quite common on campuses throughout America and it is a press which is primarily concerned with such subjects as "college spirit" and the relatively non- controversial aspects of campus life.

Just the other day I was talking about this problem with another college president who has the tradition of a supervised paper on his campus and he not only confirmed this observation to me but he went on to say that he often yearned for the vigor and the comparatively greater maturity of a student paper which addressed itself occasionally to the controversial issues of the world. I reminded him of the price which we pay for having that kind of journalism on this campus and his reply was, "Yes, but the other way you probably pay a higher price without knowing it."

I should like to comment on a practical application of this principle as it relates to TheDartmouth. I am sure it is fair to say that the editor of the Daily Dartmouth this past year did not speak as a representative voice of the College community, either students or faculty. I think it is conservative to say that there have been only rare occasions when he represented a majority point of view. Personally I am very hard put to it to recall a half dozen editorials during the past year which either expressed mv point of view or put the matter as I would have put it. and neither i nor my associates were able to develop anything approaching a normal relationship of communication, let alone cooperation, with the editor whose term ended last month. I might say that the latter aspect of the problem is a new one so far as I am concerned and one which in so far as it is in my power will not be permitted to become a part of the tradition of a free press on this campus. The point, however, which I want to make here is that the problem we face in these matters is not primarily one of protecting the comparative freedom of a few student editors to have their say in their paper, nor is it ultimately an issue of the principle of the freedom of the press in American society; rather I think it is a question of educational policy for an institution of higher education pursuing the educational objectives I mentioned above.

I am prepared to guess that however strong the disagreement was in this community with the editorial policies of The Dartmouth this past year, there would have been much greater disagreement both on the part of students and faculty with any attempt to use the authority of the College to curb the free expression of political opinion by the paper. And I am clear that any such move would immediately and effectively teach disrespect for American principles of freedom and thereby weaken the confidence of our students in both those principles and in the integrity of higher education itself.

I do not want to be understood as believing that it is impossible for a student paper to get beyond tolerable bounds of law and public decency where disciplinary action is made necessary, but I do believe that there is more at stake in the problem than most people realize and that experience has shown that it is far safer to err on the side of freedom than restriction in these matters, particularly where the offenses complained of involve issues of public and political affairs on which opinions are being violently debated and expressed throughout our society. Let me just add two bits of evidence from the past which seem to me to support this view.

In 1937, President Hopkins initiated a study of the problem of The Dartmouth. A joint committee of faculty, alumni and students under the chairmanship of Francis H. Horan, Esquire '22 went into the matter with great thoroughness. The report made by that committee is the best statement of the problem I have seen anywhere. Needless to say, the committee was deeply perplexed by the dilemmas I've mentioned, but after all was said and weighed, the conclusion reached was against changing the fundamental tenets of the Dartmouth tradition governing these matters.

Likewise I attach significance to the fact that the only thing on which President Emeritus Hopkins has seen fit to take public issue with The Dartmouth since his retirement was an editorial statement to the effect that at one point during his administration be had sought to subject the paper to administrative censorship. I need hardly remind any one who remembers the public issues of the late .thirties and the treatment of those issues by TheDartmouth that President Hopkins' life with undergraduate journalism was on many occasions neither an easy nor pleasant one to bear.

This letter is already far too long, but I have wanted to give you just as straight and adequate a response as possible to this important problem in Dartmouth life.

I shall simply say in closing that despite the position in principle to which we are committed by tradition and conviction, I intend over the years to leave nothing undone on my part or, in so far as I can influence it, on the part of the Board of Proprietors of The Dartmouth, and of the Undergraduate Council, to help our undergraduate press to be both a free and a responsible publication. That is both a very difficult and a very important objective to achieve, but I regard it as a minimum educational objective of any free and self-respecting institution of higher learning.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1949

June 1951 By ROBERT H. ZEISER, DAVID S. VOGELS JR., JOHN F. STOCKWELL -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

June 1951 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARS, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

June 1951 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, EDWIN C. CHINLUND, GEORGE B. REDDING -

Article

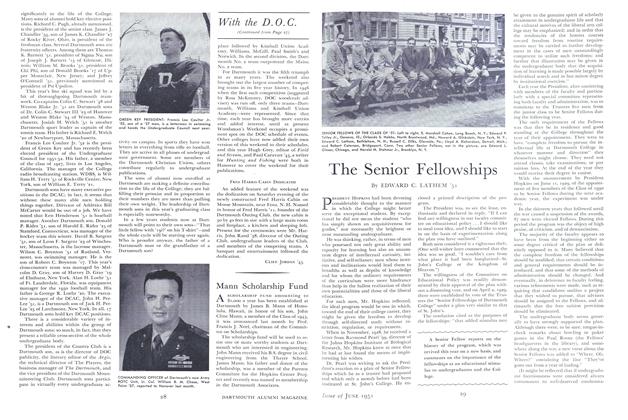

ArticleThe Senior Fellowships

June 1951 By EDWARD C. LATHEM '51 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1940

June 1951 By ELMER T. BROWNE, DONALD G. RAINIE, FREDERICK L. PORTER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1943

June 1951 By ELMER G. STEVENS JR., STANTON B. PRIDDY, THEODORE R. HOPPER