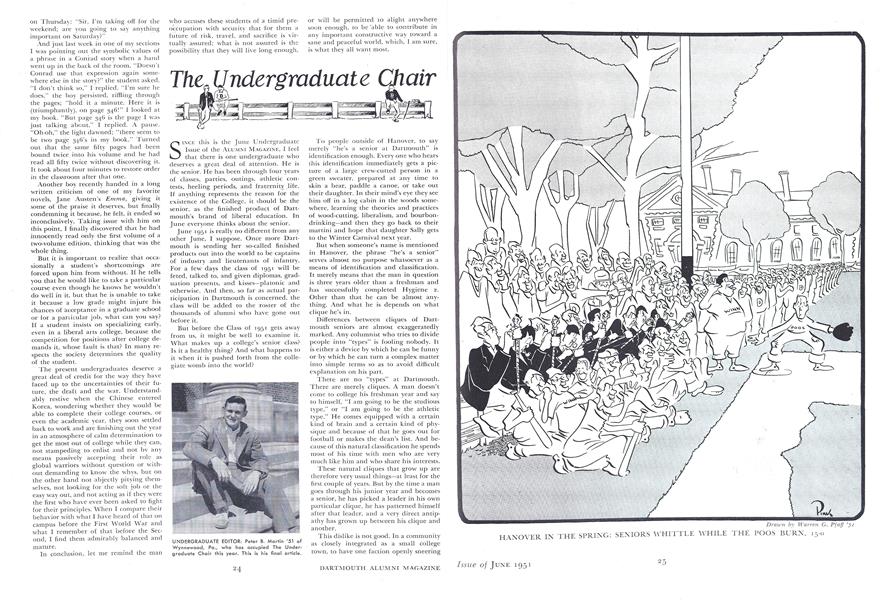

SINCE this is the June Undergraduate Issue of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE, I feel that there is one undergraduate who deserves a great deal of attention. He is the senior. He has been through four years of classes, parties, outings, athletic contests, heeling periods, and fraternity life. If anything represents the reason for the existence of the College, it should be the senior, as the finished product of Dartmouth's brand of liberal education. In June everyone thinks about the senior.

June 1951 is really no different from any other June, I suppose. Once more Dartmouth is sending her so-called finished products out into the world to be captains of industry and lieutenants of infantry. For a few days the class of 1951 will be feted, talked to, and given diplomas, graduation presents, and kisses—platonic and otherwise. And then, so far as actual participation in Dartmouth is concerned, the class will be added to the roster of the thousands of alumni who have gone out before it.

But before the Class of 1951 gets away from us, it might be well to examine it. What makes up a college's senior class? Is it a healthy thing? And what happens to it when it is pushed forth from the collegiate womb into the world?

To people outside of Hanover, to say merely "he's a senior at Dartmouth" is identification enough. Every one who hears this identification immediately gets a picture of a large crew-cutted person in a green sweater, prepared at any time to skin a bear, paddle a canoe, or take out their daughter. In their mind's eye they see him off in a log cabin in the woods some- where, learning the theories and practices of wood-cutting, liberalism, and bourbondrinking and then they go back to their martini and hope that daughter Sally gets to the Winter Carnival next year.

But when someone's name is mentioned in Hanover, the phrase "he's a senior" serves almost no purpose whatsoever as a means of identification and classification. It merely means that the man in question is three years older than a freshman and has successfully completed Hygiene 2. Other than that he can be almost anything. And what he is depends on what clique he's in.

Differences between cliques of Dartmouth seniors are almost exaggeratedly marked. Any columnist who tries to divide people into "types" is fooling nobody. It is either a device by which he can be funny or by which he can turn a complex matter into simple terms so as to avoid difficult explanation on his part.

There are no "types" at Dartmouth. There are merely cliques. A man doesn't come to college his freshman year and say to himself, "I am going to be the studious type," or "I am going to be the athletic type." He comes equipped with a certain kind of brain and a certain kind of physique and because of that he goes out for football or makes the dean's list. And because of this natural classification he spends most of his time with men who are very much like him and who share his interests.

These natural cliques that grow up are therefore very usual things—at least for the first couple of years. But by the time a mail goes through his junior year and becomes a senior, he has picked a leader in his own particular clique, he has patterned himself after that leader, and a very direct antipathy has grown up between his clique and another.

This dislike is not good. In a community as closely integrated as a small college town, to have one faction openly sneering at another is a poor thing and is bound to present a disorganized and disrupted appearance to the outside world.

Sometimes these cliques are very subtle and hard to detect. Sometimes a man finds himself in two cliques. When a man turns out to be a candidate for two cliques, say the intellectual and the athletic, it is a good thing and a point in favor of Dartmouth's screening process which supposedly picks out the "well-rounded boy." If a boy is wanted by, and can mix with two groups, it should be a good thing. But Dartmouth cliques are jealous, and a leader of one clique, by means of sly innuendo and uncomplimentary remarks, will let the two-clique boy know that he is jeopardizing his social standing and his popularity by associating with the queers in another clique.

Thus the intellectuals steer clear of the athletes. Athletes are "punchy thugs" and the insides of their skulls are like the insides of a football. The intellectuals in turn are "that bunch of pinkos." The men interested in fraternity life are the "Greeks." The men not in fraternities are

"barbarians" (naturally, not being Greeks) or "damned independents." The tone-deaf men think the men in the Glee Club are odd; the people who can't put one word after another call the writers "pseudo-in- tellectuals." Almost every man on campus has a handy name he can call the people he doesn't understand.

Natural selectivity is a good thing. A man should be free to choose his friends. But he also should be free to choose his enemies, if he has to have any. A list of enemies should not be prescribed for a man just because he happens to be in a certain fraternity or because he plays golf or writes for the humor magazine. This is a bad thing, this blind snobbishness, and can and does lead to serious consequences.

When a senior class graduates and stays away from Hanover for five or six years, things change. The belly begins to protrude a little, people get married, go places, get jobs—each man undergoes a very distinct change. The man who was a wheel on the campus is no different from the guy who just got through. And at the fifth reunion men can meet people who were in other cliques during undergraduate days and find that there is nothing really wrong with them after all. College days are gone, though, and after a few days at the reunion the class splits up again and the alumnus goes home realizing that he is meeting his classmates a little too late. Here it is June, and I am realizing the same thing; and it's late already.

Perhaps it seems wrong to think of such unhappy things in June when it is warm and the grass is green in the Bema and there are so few days left, but the more I think about it, the worse the situation grows in my mind. When my friends read this column they're going to be a little puzzled. It seems an odd place to register such a protest. For everyone who reads this magazine it may be too late to start thinking about college snobbishness and cliqueism.

But most of us will be sending sons and daughters to college some day—and most of us will take time every once in a while to remember college. It might be well, when we're thinking about college, to think about some of the poorer aspects as well as the golden-auraed walls of ivy.

This is my swan-song. And as such, it is only right that I take time and space to give thanks. The most important thing to be thankful for is that Dartmouth College is the kind of college it is. When things are as tense (security-wise) as they are today, a liberal arts college that is really liberal is a rarity, and Dartmouth is that kind of college. The newspaper is allowed to print what it wants and feels, and I am allowed to blow off steam about undergraduate things here without any check rein.

So I want to thank the following: (1) You, for reading these articles. (2) Charlie Widmayer, for giving me the chance to write them. (3) Dartmouth, for being what it is. (4) Mr. and Mrs. Pete Martin, for sending me here.

UNDERGRADUATE EDITOR: Peter B. Martin '51 of Wynnewood, Pa., who has occupied The Undergraduate Chair this year. This is his final article.

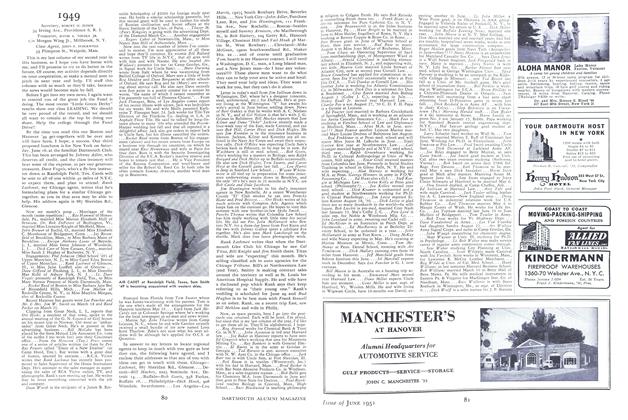

HANOVER IN THE SPRING: SENIORS WHITTLE WHILE THE POOS BURN, 15-0

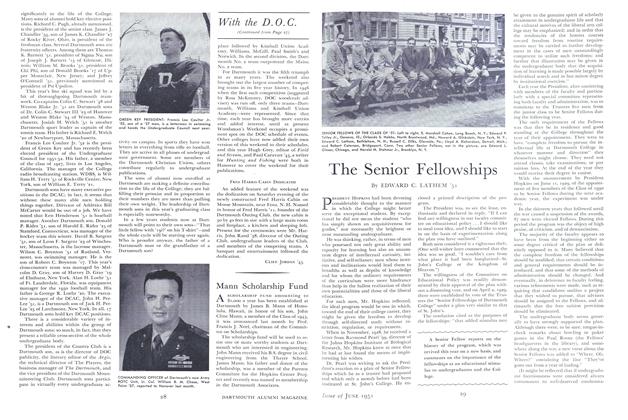

STRENUOUS EFFORT AT THE WOODSMAN'S WEEKEND: Left, demonstrating their lung power in the fire-building contest are Wes Blake '51 (left), who was co-captain of the ski team this year, and Bill Biddle '52, new president of the D.O.C. Right, the Kimball Union Academy team in action in the pulp-throwing.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1949

June 1951 By ROBERT H. ZEISER, DAVID S. VOGELS JR., JOHN F. STOCKWELL -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

June 1951 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARS, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

June 1951 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, EDWIN C. CHINLUND, GEORGE B. REDDING -

Article

ArticleThe Senior Fellowships

June 1951 By EDWARD C. LATHEM '51 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1940

June 1951 By ELMER T. BROWNE, DONALD G. RAINIE, FREDERICK L. PORTER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1943

June 1951 By ELMER G. STEVENS JR., STANTON B. PRIDDY, THEODORE R. HOPPER

PETE MARTIN '51

Article

-

Article

ArticleMEETING OF THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES

January 1924 -

Article

ArticleAlumni College Anyone ?

MARCH 1968 -

Article

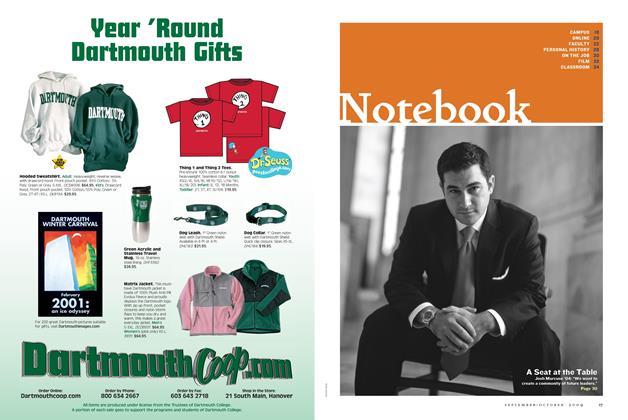

ArticleNotebook

Sept/Oct 2009 By DAVID DEAL -

Article

ArticleThayer School

March 1960 By EDWARD S. BROWN '35 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

November 1946 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleTHE ROVING REPORTER SAW

MARCH 1932 By W. H. Ferry '32