DARTMOUTH and the War: About 20 men have dropped out of Dartmouth for the time being to join the branch of service of their choice. During the Christmas vacation these men checked with their draft boards and found that they were due to be called soon for their selective service physicals. The ruling then was that after a man had been called up for his physical he could not enlist in any branch of the service. In order to have a free choice as to their type of service, these men left school and enlisted before examination orders arrived.

These are obviously momentous times, times when the Great Issues course, required of all seniors, should take on new meaning as a means of bridging the gap between academic and post-graduate (military) life. Looked at in its sense of focusing thought beyond the limits of the campus and the hockey rink, the course is an admirable (and much imitated) thing.

This year the course has had an outstanding roster of speakers: the late John McLane Clark '32, editor and publisher of the Claremont Daily Eagle; Herbert B. Elliston, editor of The Washington Post; Cedric Foster, '24, newscaster for the Yankee Network; T. V. Smith, professor of citizenship and philosophy, Syracuse University; Llewellyn B. White, National Affairs Editor of The Reporter; and many others. The seniors have been required to keep posted on what's going on in the news by reading newspapers and listening to radio commentators. They have had to fulfill certain requirements in outside reading.

This is all well and good, and should tend to keep the senior class well-informed and in touch with things. In order to crystallize the thinking that speakers, newspaper readings and outside assignments have supposedly stimulated in the senior-class mind, hour exams are given. This year the seniors have had two such exams, prepared by the steering committee in the Public Affairs Laboratory in Baker Library.

The way seniors are expected to prepare for these exams is (a) to listen carefully to the speakers who express their viewpoints in the off-the-record talks Monday night in 105 Dartmouth Hall, (b) to read the newspaper everyday to keep up on world affairs, (c) to sample editorial opinion in these newspapers, looking out for bias and slanted reporting, (d) to read the assigned outside reading carefully, and (e) to keep posted on the exhibits in the Public Affairs Laboratory. In preparing for the first hour exam, a fairly unknown quantity, most seniors did all of these things with varying degrees of care. Personally, I kept fairly well up on our current events, listened to a few broadcasts by Edward R. Murrow and Fulton Lewis Jr., did the outside reading, and attended all the Great Issues lectures given by visiting speakers.

I looked fairly carefully at the exhibits in the P.A.L. and did some editorial opinion sampling among the newspapers on exhibit there. When the time came, I felt well prepared. I went into 105 Dartmouth expecting a tough exam, to be sure, but one that would cover the required material and at the same time help me assemble all my miscellaneous information into a more coherent whole.

When I came out of the exam, my first reaction was to laugh. I had just waded through sixty minutes of the most ambiguous, unimportant questions I had ever seen. It reminded me a little of a history professor I had had in high school who always asked questions about the footnotes in the history book and then felt hurt when people didn't get the answers right. I got a C.

For the second exam, my tactics of preparation changed somewhat. I tried to keep posted on what was going on in the news and I attended the Great Issues lectures (which are interesting in themselves apart from being a requirement of the course). Other than that I did nothing. I did not do the outside reading. I did not look at the exhibits in the P.A.L. with great care. I did no sampling of editorial opinion in papers other than the New York HeraldTribune, the New York World Telegramand Sun, and The Dartmouth, all of which' I subscribe to anyway.

My roommates followed pretty much the same course. One of them actually did the outside reading assignment. The night before the exam I attended a fraternity house seminar given by a government major who reviewed the lecturers for us and gave us a list of "people in the news" to memorize.

The exam followed the pattern set by the first, except that the questions were, if anything, more ambiguous than before. It had been a large guessing game, with impressive-looking question sheets and machine-scored answer blanks. No one had the slightest idea how he had done in the exam.

When Christmas vacation was over, the marks were posted in the P.A.L. I got a B-minus. My roommate (the one who did the outside reading assignments) got a C-plus. And the other roommate who followed the same study plan as I did got a C. As far as I can tell, the exams didn't help my thinking in any way whatsoeverand I haven't the slightest idea how to prepare for the final.

I can well understand how difficult it must be to make up an hour exam in a course of so wide a scope as Great Issues. It is obvious to the seniors that the difficulty has not been well met.

Perhaps the course should merely consist of a series of compulsory lectures coupled with required subscription to at least two newspapers. In this way the senior could get his hours' credit towards his degree without subjecting himself to the vagaries of Great Issues exam marking. And, at the same time, he would be reaping from the course the same benefits he is receiving now—the advantages of hearing interesting speakers who have something worthwhile to say—and the advantage of keeping up to date on what is going on in the world.

Perhaps one benefit of the G. I. exams is that the senior class is brought closer together by something in common to joke about. It is too bad that the joke is on something as fundamentally worthwhile as Great Issues.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleThe Student Days of Richard Hovey

February 1951 By EDWARD C. LATHEM '51 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

February 1951 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, EDWIN C. CHINLUND, JACK D. GUNTHER -

Article

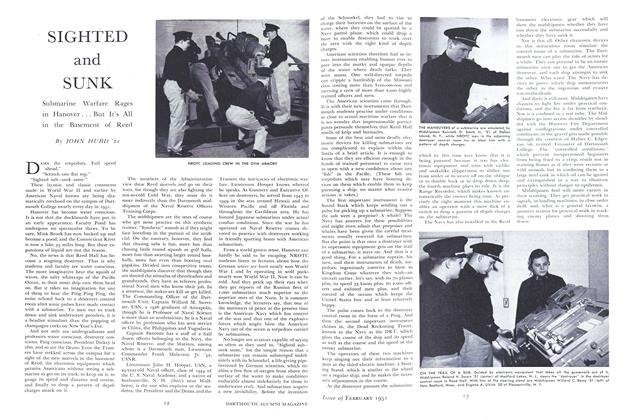

ArticleSIGHTED and SUNK

February 1951 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

February 1951 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, DAVID L. GARRATT -

Class Notes

Class Notes1933

February 1951 By GEORGE F. THERIAULT, LEE W. ECKELS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1905

February 1951 By GEORGE W. PUTNAM, GILBERT H. FALL

Pete Martin '51

Article

-

Article

ArticleNext Council Meeting

November 1934 -

Article

ArticleTimberland Bought

April 1956 -

Article

ArticleSOUVENIR BOOKLET

DECEMBER 1962 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Days — 60 Years Ago

DECEMBER 1972 -

Article

Article. . . And the Curriculum

JAN./FEB. 1979 -

Article

ArticleDallas Golfers Qualify for National Finals

OCTOBER 1989 By Mickey Stuart '71