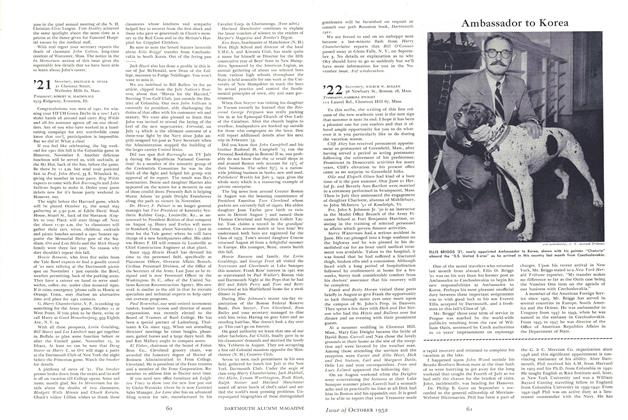

LANGUOROUSLY stretched out, all fluffy tulle and platinum hair except for a Dietrichesque silken leg stretched out with a coy garter at the upper extremity, Jean Harlow was holding the hand of the Dean of Dartmouth College, who, at something less than arm's length but under control, was looking down at her. Though in Hollywood, Craven Laycock was wearing his rimless spectacles and a salt-andpepper suit. Cameras flashed, and newspapers smirked their satisfaction.

"This will give them something to talk about back home," the Dean remarked dryly, and it certainly did.

From then on, Dartmouth liked to make a distinction between the Dean the Dean and the Dean the Man.

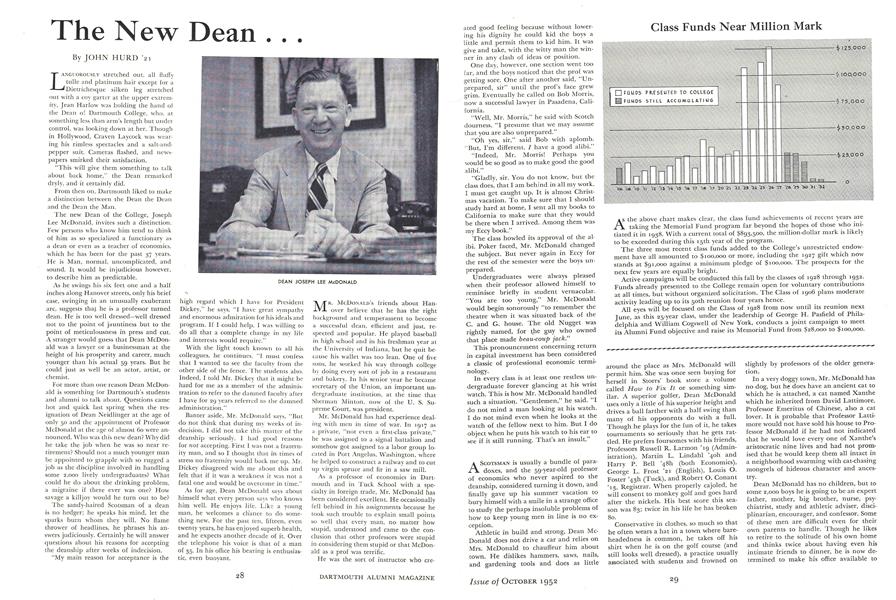

The new Dean of the College, Joseph Lee McDonald, invites such a distinction. Few persons who know him tend to think of him as so specialized a functionary as a dean or even as a teacher of economics, which he has been for the past 37 years. He is Man, normal, uncomplicated, and sound. It would be injudicious however, to describe him as predictable.

As he swings his six feet one and a half inches along Hanover streets, only his brief case, swinging in an unusually exuberant arc, suggests thaj. he is a professor turned dean. He is too well dressed—well dressed not to the point of jauntiness but to the point of meticulousness in press and cut. A stranger would guess that Dean McDonald was a lawyer or a businessman at the height of his prosperity and career, much younger than his actual 59 years. But he could just as well be an actor, artist, or chemist.

For more than one reason Dean McDonald is something (or Dartmouth's students and alumni to talk about. Questions came hot and quick last spring when the resignation of Dean Neidlinger at the age of only 50 and the appointment of Professor McDonald at the age of almost 60 were announced. Who was this new dean? Why did he take the job when he was so near retirement? Should not a much younger man be appointed to grapple with so rugged a job as the discipline involved in handling some 2,000 lively undergraduates? What could he do about the drinking problem, a migraine if there ever was one? How savage a killjoy would he turn out to be?

The sandy-haired Scotsman of a dean is no hedger; he speaks his mind, let the sparks burn whom they will. No flame thrower of headlines, he phrases his answers judiciously. Certainly he will answer questions about his reasons for accepting the deanship after weeks of indecision.

"My main reason for acceptance is the high regard which I have for President Dickey," he says. "I have great sympathy and enormous admiration for his ideals and program. If I could help, I was willing to do all that a complete change in my life and interests would require."

With the light touch known to all his colleagues, he continues, "I must confess that I wanted to see the faculty from the other side of the fence. The students also. Indeed, I told Mr. Dickey that it might be hard for me as a member of the administration to refer to the damned faculty after I have for 29 years referred to the damned administration."

Banter aside, Mr. McDonald says, "But do not think that during my weeks of indecision, I did not take this matter of the deanship seriously. I had good reasons for not accepting. First I was not a fraternity man, and so I thought that in times of stress no fraternity would back me up. Mr. Dickey disagreed with me about this and felt that if it was a weakness it was not a fatal one and would be overcome in time."

As for age, Dean McDonald says about himself what every person says who knows him well. He enjoys life. Like a young man, he welcomes a chance to do something new. For the past ten, fifteen, even twenty years, he has enjoyed superb health, and he expects another decade of it. Over the telephone his voice is that of a man of 35. In his office his bearing is enthusiastic, even buoyant.

MR. MCDONALD'S friends about Hanover believe that he has the right background and temperament to become a successful dean, efficient and just, respected and popular. He played baseball in high school and in his freshman year at the University of Indiana, but he quit because his wallet was too lean. One of five sons, he worked his way through college by doing every sort of job in a restaurant and bakery. In his senior year he became secretary of the Union, an important undergraduate institution, at the time that Sherman Minton, now of the U. S. Su-preme Court, was president.

Mr. McDonald has had experience dealing with men in time of war. In 1917 as a private, "not even a first-class private," he was assigned to a signal battalion and somehow got assigned to a labor group located in Port Angelus, Washington, where he helped to construct a railway and to cut up virgin spruce and fir in a saw mill.

As a professor of economics in Dartmouth and in Tuck School with a specialty in foreign trade, Mr. McDonald has been considered excellent. He occasionally fell behind in his assignments because he took such trouble to explain small points so well that every man, no matter how stupid, understood and came to the conclusion that other professors were stupid in considering them stupid or that McDonald as a prof was terrific.

He was the sort of instructor who ereated good feeling because without lowering his dignity he could kid the boys a little and permit them to kid him. It was give and take, with the witty man the winner in any clash of ideas or position.

One day, however, one section went too far, and the boys noticed that the prof was getting sore. One after another said, "Unprepared, sir" until the prof's face grew grim. Eventually he called on Bob Morris, now a successful lawyer in Pasadena, California.

"Well, Mr. Morris," he said with Scotch dourness. "I presume that we may assume that you are also unprepared."

"Oh yes, sir," said Bob with aplomb. "But, I'm different. I have a good alibi."

"Indeed, Mr. Morris! Perhaps you would be so good as to make good the good alibi."

"Gladly, sir. You do not know, but the class does, that I am behind in all my work. I must get caught up. It is almost Christmas vacation. To make sure that I should study hard at home, I sent all my books to California to make sure that they would be there when I arrived. Among them was my Eccy book."

The class howled its approval of the alibi. Poker faced, Mr. McDonald changed the subject. But never again in Eccy for the rest of the semester were the boys unprepared.

Undergraduates were always pleased when their professor allowed himself to reminisce briefly in student vernacular. "You are too young," Mr. McDonald would begin sonorously "to remember the theatre when it was situated back of the C. and G. house. The old Nugget was rightly named, for the guy who owned that place made beau-coup jack."

This pronouncement concerning return in capital investment has been considered a classic of professional economic terminology.

In every class is at least one restless undergraduate forever glancing at his wrist watch. This is how Mr. McDonald handled such a situation. "Gentlemen," he said. "I do not mind a man looking at his watch. I do not mind even when he looks at the watch of the fellow next to him. But I do object when he puts his watch to his ear to see if it still running. That's an insult."

A SCOTSMAN is usually a bundle of paradoxes, and the 59-year-old professor of economics who never aspired to the deanship, considered turning it down, and finally gave up his summer vacation to bury himself with a smile in a strange office to study the perhaps insoluble problems of how to keep young men in line is no exception.

Athletic in build and strong, Dean Mc-Donald does not drive a car and relies on Mrs. McDonald to chauffeur him about town. He dislikes hammers, saws, nails, and gardening tools and does as little around the place as Mrs. McDonald will permit him. She was once seen buying for herself in Storrs' book store a volume called How to Fix It or something similar. A superior golfer, Dean McDonald uses only a little of his superior height and drives a ball farther with a half swing than many of his opponents do with a full. Though he plays for the fun of it, he takes tournaments so seriously that he gets rattled. He prefers foursomes with his friends, Professors Russell R. Larmon 'l9 (Administration), Martin L. Lindahl 4011 and Harry P. Bell '4BII (both Economics), George L. Frost '2l (English), Louis O. Foster '4311 (Tuck), and Robert O. Conant 'l3, Registrar. When properly cajoled, he will consent to monkey golf and goes hard after the nickels. His best score this season was 83; twice in his life he has broken 80.

Conservative in clothes, so much so that he often wears a hat in a town where bareheadedness is common, he takes off his shirt when he is on the golf course (and still looks well dressed), a practice usually associated with students and frowned on slightly by professors of the older generation.

In a very doggy town, Mr. McDonald has no dog, but he does have an ancient cat to which he is attached, a cat named Xanthe which he inherited from David Lattimore, Professor Emeritus of Chinese, also a cat lover. It is probable that Professor Lattimore would not have sold his house to Professor McDonald if he had not indicated that he would love every one of Xanthe's aristocratic nine lives and had not promised that he would keep them all intact in a neighborhood swarming with cat-chasing mongrels of hideous character and ancestry.

Dean McDonald has no children, but to some 2,000 boys he is going to be an expert father, mother, big brother, nurse, psychiatrist, study and athletic adviser, disciplinarian, encourager, and confessor. Some of these men are difficult even for their own parents to handle. Though he likes to retire to the solitude of his own home and thinks twice about having even his intimate friends to dinner, he is now determined to make his office available to students for hours on end and to encourage them to talk to him as man to man, quietly, reasonably, and honestly. As Dean he will come in for more entertaining and being entertained in administration circles than he has had for the past 29 years, and he expects to enjoy it.

A graduate of the University ot Indiana with a Master's degree from Columbia, who has taught at the University of Pennsylvania and the University of Minnesota, Mr. McDonald is happy and proud to be an honorary member of the Dartmouth class of 1920, which is also the class of Pro fessors Frey (Tuck), Carter (Economics), Foley (History), Amsden (Chemistry), and Goddard (Astronomy), and Paul Sample (Artist in Residence). (For pictorial evidence of the way in which Dean McDonald feels at home in the 1920 class tent, see the 1920 notes in this issue.)

"That membership is one of the brighest jewels in my crown," says Dean Mc-Donald without attempting to scintillate.

One of the best speakers on the Faculty, who has even pinch-hit in Public Speaking courses, he is no man to fold his hands over his stomach and talk, talk, talk like some committee men who think that committee meetings are fun. When McDonald speaks, he says something cogent and sensible. A serious man fundamentally, he can sometimes with a barbed witticism con vulse a serious meeting and clear the air of cant.

Independent in his thought and behavior, Dean McDonald is nevertheless no bull in "k China shop and moves sensitively among established values. He has loyalty. As president of the local chapter of the American Association of University Professors, he had the courage to attempt what few men on the Faculty would have. Given a mandate by the chapter, he interviewed authorities in the Administration Building to seek a detailed explanation of the significance of the condensed, almost meaningless, figures in the annual financial report of the College. Professors, he believed, have a right to understand how much money is coming in and how it is being spent and where they stand in relation to Dartmouth's financial policy.

In summarizing his findings at a meeting of the AAUP, Mr. McDonald displayed his loyalty to the Faculty and his independence of the Administration in a closely woven financial exegesis that cleared up ambiguities. Then, no turncoat, he displayed his loyalty to the Administration and his independence of the Faculty by making clear his appreciation of the sound financial vision shown by presidents and treasurers past and present with the advice and approval of the Trustees. Everybody felt good.

It is almost unthinkable that any other Dartmouth professor could have embarked on an enterprise requiring so much courage and tact and seen it through. It is even more unthinkable that any other Dartmouth professor could have won the con- fidence of both the Faculty and the Administration. An indication of McDonald success is that the President asked him to become Dean of the College and that the Faculty feels sure that no better man could represent them and their interests in the Administration Building, which sometimes seems far removed from classrooms.

As dean, Craven Laycock never expected to find himself in such close quarters with Jean Harlow, sultriest of movie stars. Deans must be adaptable persons, for they may run into almost any kind of person or situation. Hollywood B comedy and real tragedy are some of the situations which drift from time to time into a dean's office.

Joseph L. McDonald is ready and poise( for anything.

Join College Staff

Two young Dartmouth graduates joined the College administrative staff this summer and a third has assumed a post in Baker Library. Gardiner Bridge '42 is the new Assistant to the Director of Admissions, taking the place of John H. Emerson '38, who has returned to teaching. Orton H. Hicks Jr. '49 became Assistant to the Dean of the College, while Edward C. Lathem '51 assumed the duties of Assistant to the Librarian, succeeding William R. Lansberg '38, now Head of Acquisitions.

Mr. Bridge comes to Dartmouth from Hebron Academy where he taught English for six years.

Mr. Hicks, who made Phi Beta Kappa and was a Rufus Choate Scholar while an undergraduate, received the M.C.S. degree from Tuck School in 1950. He spent the past year at the University of Copenhagen, continuing studies in economic geography.

Mr. Lathem, who received the Campbell Fellowship for the study of library science at Columbia University and who received the M.S. degree in June, was a Senior Fellow at Dartmouth.

Gifts to Library

THE Friends of the Dartmouth Library continued active throughout the summer and several gifts were added to Baker collections.

James D. Landauer '23 was the donor of an outstanding collection of 92 original wood engravings signed by Timothy Cole, together with critical material on this famous wood engraver.

William D. Blatner '05 presented a large collection of Dartmouth College material, as well as Lincoln pamphlets and reprints of Natural History; the original copies of The London Aphrodite; Robinson Jeffer's Tamar; autographed Stephens material; Masefield's Shakespeare and theSpiritual Life; and Cruikshank drawings.

Other valuable gifts were made by Henry S. Embree '30, J. McGregor Stewart, Erskine Caldwell, William H. McCarter '19, George Matthew Adams, Thomas W-Streeter '04, Victor Reynolds '27, Ernest H. Moore '31, Robert M. Stecher '19, Mrs. Bella C. Landauer, Prof. James F. Beard, William Steck '31, J. Alrnus Russell '20, and Herbert F. West '22.

DEAN JOSEPH LEE McDONALD

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

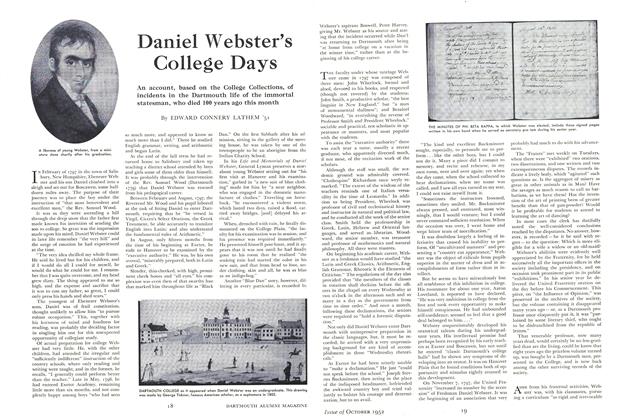

ArticleDaniel Webster's College Days

October 1952 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51 -

Article

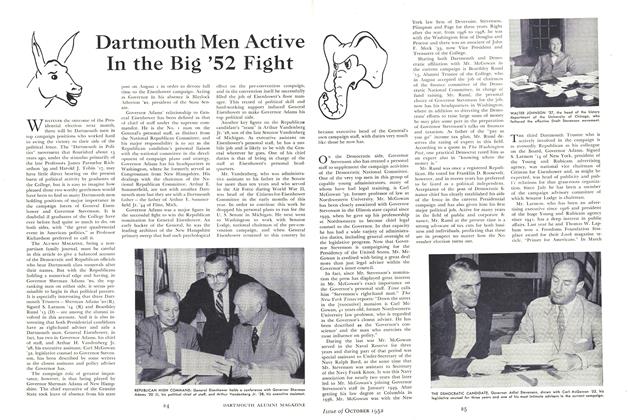

ArticleDartmouth Men Active In the Big '52 Fight

October 1952 By C. E. W. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

October 1952 By ERNEST H. EARLEY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1905

October 1952 By GEORGE W. PUTNAM, GILBERT H. FALL -

Class Notes

Class Notes1948

October 1952 By FRANCIS R. DRURY JR., ROBERT L. MERRIAM -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921

October 1952 By REGINALD B. MINER, ROBERT M. MACDONALD

JOHN HURD '21

-

Books

BooksALL THE BEST IN THE SOUTH PACIFIC.

June 1961 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Feature

FeatureDid Webster Really Say It?

JANUARY 1966 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksFEEL FREE.

DECEMBER 1971 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksNO TIME FOR SCHOOL, NO TIME FOR PLAY: THE STORY OF CHILD LABOR IN AMERICA.

NOVEMBER 1972 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksNEW JERSEY HISTORICAL PROFILES REVOLUTIONARY TIMES.

April 1974 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksBull Market

September 1975 By JOHN HURD '21

Article

-

Article

ArticlePRESIDENT SUGGESTS LIMIT TO POSSIBLE GROWTH

January 1920 -

Article

ArticleDirector McCarter Travels

March 1931 -

Article

ArticleThe Debaters

February 1975 -

Article

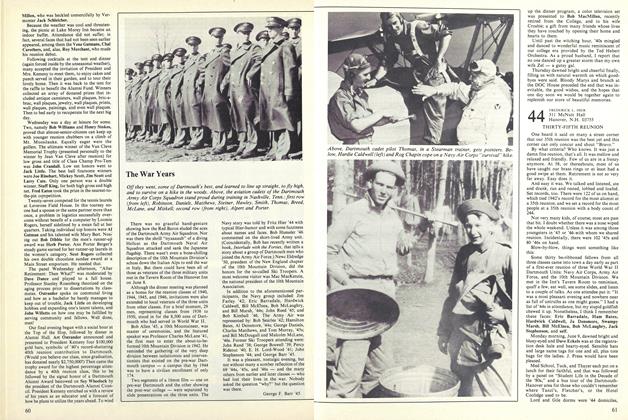

ArticleThe War Years

September 1980 By George F. Barr '45 -

Article

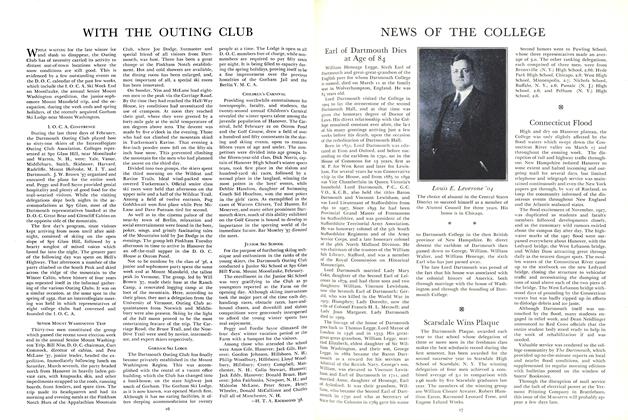

ArticleWITH THE OUTING CLUB

April 1936 By H.T.A. Richmond '38 -

Article

ArticleA legacy's lament

NOVEMBER 1986 By Jock McDonald '87