VOICES crying in the wilderness, the eight Dartmouth men, all clergymen, who were the first presidents of colleges and universities lived up to the College motto, Vox clamantis indeserto, and emulated Eleazar Wheelock in Christian zeal. Able to read Hebrew, they could have understood why modern scholars and the American Revised Version of the Bible prefer a different translation from Isaiah, "The voice of one that crieth, Prepare ye in the wilderness the way." The presidents were more than voices; men of action, they pioneered on rugged wilderness paths. Not only presidents but also professors, learned and moral, they laid down the law for students and faculty, and woe to the defiant. They bucked trustees, pontificated as if divinely inspired, and rather than abandon their sacred trusts preferred to resign or to die.

In colleges luxuriously equipped today, one can hardly visualize the spartan simplicities facing those academic communities. Undergraduates, faculty, and presidents gloried in the life of the mind and even more in the life of the spirit.

This article treats only first presidents of colleges and universities who may also have founded them, and omits founders only, like Alden Partridge, Dartmouth 1806, founder of Norwich University in 1819, but not the first president.

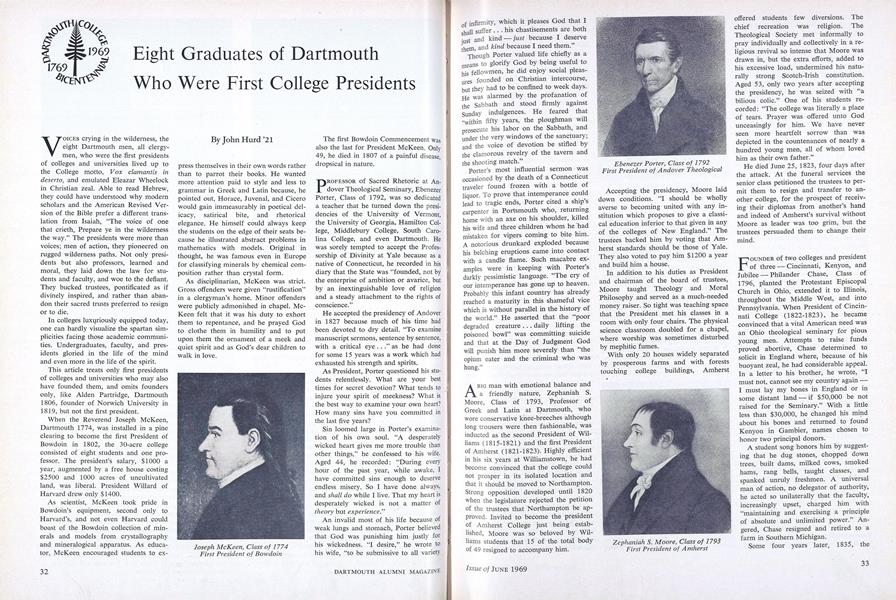

When the Reverend Joseph McKeen, Dartmouth 1774, was installed in a pine clearing to become the first President of Bowdoin in 1802, the 30-acre college consisted of eight students and one professor. The president's salary, $1000 a year, augmented by a free house costing $2500 and 1000 acres of uncultivated land, was liberal. President Willard of Harvard drew only $1400.

As scientist, McKeen took pride in Bowdoin's equipment, second only to Harvard's, and not even Harvard could boast of the Bowdoin collection of minerals and models from crystallography and mineralogical apparatus. As educator, McKeen encouraged students to express themselves in their own words rather than to parrot their books. He wanted more attention paid to style and less to grammar in Greek and Latin because, he pointed out, Horace, Juvenal, and Cicero would gain immeasurably in poetical delicacy, satirical bite, and rhetorical elegance. He himself could always keep the students on the edge of their seats because he illustrated abstract problems in mathematics with models. Original in thought, he was famous even in Europe for classifying minerals by chemical composition rather than crystal form.

As disciplinarian, McKeen was strict. Gross offenders were given "rustification" in a clergyman's home. Minor offenders were publicly admonished in chapel. McKeen felt that it was his duty to exhort them to repentance, and he prayed God to clothe them in humility and to put upon them the ornament of a meek and quiet spirit and as God's dear children to walk in love.

The first Bowdoin Commencement was also the last for President McKeen. Only 49, he died in 1807 of a painful disease, dropsical in nature.

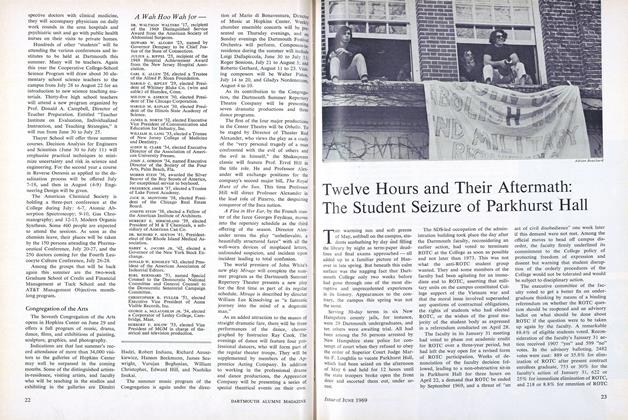

PROFESSOR of Sacred Rhetoric at Andover Theological Seminary, Ebenezer Porter, Class of 1792, was so dedicated a teacher that he turned down the presidencies of the University of Vermont, the University of Georgia, Hamilton College, Middlebury College, South Carolina College, and even Dartmouth. He was sorely tempted to accept the Professorship of Divinity at Yale because as a native of Connecticut, he recorded in his diary that the State was "founded, not by the enterprise of ambition or avarice, but by an inextinguishable love of religion and a steady attachment to the rights of conscience."

He accepted the presidency of Andover in 1827 because much of his time had been devoted to dry detail. "To examine manuscript sermons, sentence by sentence, with a critical eye. . as he had done for some 15 years was a work which had exhausted his strength and spirits.

As President, Porter questioned his students relentlessly. What are your best times for secret devotion? What tends to injure your spirit of meekness? What is the best way to examine your own heart? How many sins have you committed in the last five years?

Sin loomed large in Porter's examination of his own soul. "A desperately wicked heart gives me more trouble than other things," he confessed to his wife. Aged 44, he recorded: "During every hour of the past year, while awake, I have committed sins enough to deserve endless misery. So I have done always, and shall do while I live. That my heart is desperately wicked is not a matter of theory but experience."

An invalid most of his life because of weak lungs and stomach, Porter believed that God was punishing him justly for his wickedness. "I desire," he wrote to his wife, "to be submissive to all variety of infirmity, which it pleases God that I shall suffer ... his chastisements are both just and kind - just because I deserve them, and kind because I need them."

Though Porter valued life chiefly as a means to glorify God by being useful to his fellowmen, he did enjoy social pleasures founded on Christian intercourse, but they had to be confined to week days. He Was alarmed by the profanation of the Sabbath and stood firmly against Sunday indulgences. He feared that "within fifty years, the ploughman will prosecute his labor on the Sabbath, and under the very windows of the sanctuary; and the voice of devotion be stifled by the clamorous revelry of the tavern and the shooting match."

Porter's most influential sermon was occasioned by the death of a Connecticut traveler found frozen with a bottle of liquor. To prove that intemperance could lead to tragic ends, Porter cited a ship's carpenter in Portsmouth who, returning home with an axe on his shoulder, killed his wife and three children whom he had mistaken for vipers coming to bite him. A notorious drunkard exploded because his belching eruptions came into contact with a candle flame. Such macabre examples were in keeping with Porter's darkly pessimistic language. "The cry of our intemperance has gone up to heaven. Probably this infant country has already reached a maturity in this shameful vice which is without parallel in the history of the world." He asserted that the "poor degraded creature .. . daily lifting the poisoned bowl" was committing suicide and that at the Day of Judgment God will punish him more severely than "the opium eater and the criminal who was hung."

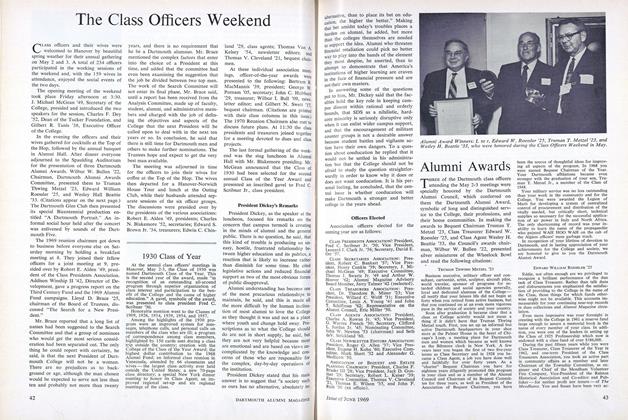

A BIG man with emotional balance and a friendly nature, Zephaniah S. Moore, Class of 1793, Professor of Greek and Latin at Dartmouth, who wore conservative knee-breeches although long trousers were then fashionable, was inducted as the second President of Wil- liams (1815-1821) and the first President of Amherst (1821-1823). Highly efficient in his six years at Williamstown, he had become convinced that the college could not prosper in its isolated location and that it should be moved to Northampton. Strong opposition developed until 1820 when the legislature rejected the petition of the trustees that Northampton be approved. Invited to become the president of Amherst College just being established, Moore was so beloved by Williams students that 15 of the total body of 49 resigned to accompany him.

Accepting the presidency, Moore laid down conditions. "I should be wholly averse to becoming united with any institution which proposes to give a classi- cal education inferior to that given in any of the colleges of New England." The trustees backed him by voting that Amherst standards should be those of Yale. They also voted to pay him $1200 a year and build him a house.

In addition to his duties as President and chairman of the board of trustees, Moore taught Theology and Moral Philosophy and served as a much-needed money raiser. So tight was teaching space that the President met his classes in a room with only four chairs. The physical science classroom doubled for a chapel, where worship was sometimes disturbed by mephitic fumes.

With only 20 houses widely separated by prosperous farms and with forests touching college buildings, Amherst offiered students few diversions. The chief recreation was religion. The Theological Society met informally to pray individually and collectively in a religious revival so intense that Moore was drawn in, but the extra efforts, added to his excessive load, undermined his naturally strong Scotch-Irish constitution. Aged 53, only two years after accepting the presidency, he was seized with "a bilious colic." One of his students recorded: "The college was literally a place of tears. Prayer was offered unto God unceasingly for him. We have never seen more heartfelt sorrow than was depicted in the countenances of nearly a hundred young men, all of whom loved him as their own father."

He died June 25, 1823, four days after the attack. At the funeral services the senior class petitioned the trustees to permit them to resign and transfer to another college, for the prospect of receiving their diplomas from another's hand and indeed of Amherst's survival without Moore as leader was too grim, but the trustees persuaded them to change their mind.

FOUNDER of two colleges and president of three - Cincinnati, Kenyon, and Jubilee - Philander Chase, Class of 1796, planted the Protestant Episcopal Church in Ohio, extended it to Illinois, throughout the Middle West, and into Pennsylvania. When President of Cincinnati College (1822-1823), he became convinced that a vital American need was an Ohio theological seminary for pious young men. Attempts to raise funds proved abortive, Chase determined to solicit in England where, because of his buoyant zeal, he had considerable appeal. In a letter to his brother, he wrote, "I must not, cannot see my country again - I must lay my bones in England or in some distant land —if $50,000 be not raised for the Seminary." With a little less than $30,000, he changed his mind about his bones and returned to found Kenyon in Gambier, names chosen to honor two principal donors.

A student song honors him by suggesting that he dug stones, chopped down trees, built dams, milked cows, smoked hams, rang bells, taught classes, and spanked unruly freshmen. A universal man of action, no delegator of authority, he acted so unilaterally that the faculty, increasingly upset, charged him with "maintaining and exercising a principle of absolute and unlimited power." Angered, Chase resigned and retired to a farm in Southern Michigan.

Some four years later, 1835, the diocese of Illinois invited Chase to become its first bishop. Then sixty years old, he removed his family in a covered wagon to Illinois. His zeal to educate pious young men for the priesthood flared again, and he sailed for England and again his new-world enthusiasm touched hearts and purse strings. This time, the take was less, only $10,000, but it was enough to enable Chase to found Jubilee College in 1838. Hearing that a thriving German colony was situated near Jubilee, and remembering Albert's virtues, Queen Victoria, in the hope that a pious atmosphere could be cultivated, donated a box of German prayer books. Trouble with the faculty again dogged Chase but no open break occurred.

His end proved to be dramatic and characteristic. When the horse pulling his buggy panicked, the 77-year-old driver lost control and fell heavily to the ground. Lifted, he said, "You may order my coffin." As students carried him to his bed he said, "Thank you. Thank you. You will have to carry me once more only." He was laid to rest in a shady spot selected by himself in God's Acre at Jubilee.

As President of the New Hampshire College of Agriculture and Me- chanic Arts, later the University of New Hampshire, Asa Dodge Smith, Class of 1830, was at the same time President of Dartmouth College (1863-1877). He was unlike the seven Dartmouth men who became presidents because of a passionate conviction about the value of their work in inculcating piety in young men. As head of Dartmouth, he was actually opposed to the New Hampshire College being located in Hanover and hoped that it could be founded in some other town. Smith believed that the union of the two institutions could not last long, that difficulties would be sure to arise in the administration of two independent bodies, that no proof could be made that the institution was necessary. The Trustees overruled him, however, and the College came into being with a faculty of two (President Smith taught one course), an entering class of ten students, few books and little apparatus and no place to store them, no building, an insufficient endowment, and vague ideas as to what it was supposed to be doing.

Actually President Smith was only nominal head. Professor Ezekiel W. Dimond, a graduate of Middlebury, did most of the work. As business manager he acquired the farm used by New Hampshire College, ran it, planned new buildings, watched over contractors and workmen, wrote reports about progress, campaigned for money in the legislature, taught chemistry in both colleges, lectured throughout the state, campaigned for students, and even bucked President Smith when necessary, though after the Trustees had approved of the New Hampshire College, Smith became its fast friend.

It is Professor Dimond who should be called the father of the University of New Hampshire, not President Smith. The New Hampshire College was moved to Durham in 1893.

THE nineteenth century believed that women ought not to be educated, because their best career was to please men. God had created women with exquisite emotions to soften the roughness of men's careers by sweetening the home. Men were endowed with a hard head and brawny arms; women, with a soft heart and nimble fingers.

Mrs. John Adams, the President's wife, one of the most highly educated women of her time, remarked that female education even in the best families went no further than writing and arithmetic and in rare instances music and dancing. Women's intellectual diet might be summarized in the couplet: "To eat strawberries, sugar, and cream,/ Sit on a cushion and sew up a seam."

How then to account for so superior an institution as Vassar? The answer is that a self-educated and self-made man, childless and old, Matthew Vassar, a Poughkeepsie brewer with a fortune of $800,000, worried about his money. Should he give it all to his two nephews with the understanding that on their death their estates and his should be willed to a future city hospital? What did Milo P. Jewett, Dartmouth 1828, think of this plan? Bad, said Jewett. Great hospitals are for great cities, and Pough- keepsie will never exceed 50,000. Better throw your money into the Hudson River. Surprised, Vassar exclaimed petulantly, "I wish somebody would tell me what to do with my money! It's the plague of my life - keeps me awake nights - stocks going down, banks breaking, insurance companies failing."

Jewett was glad to be of service. He urged Vassar to endow and build a college for young women which could be to women what Yale and Harvard were to men. It would be "a monument more lasting than pyramids." Vassar was flattered and impressed. In keeping with the caution which amassed a fortune, he raised all sorts of objections, however, but he finally agreed to the plan. The two hostile nephews adroitly undermined Jewett's reputation and persuaded their uncle to build instead a boys' school, a girls' school, and a free library. Jewett's educational idealism and missionary eloquence proved stronger than family loyalty. "Oh, what a fall was there, my countrymen!" he exclaimed. "Your advisers have razed your magnificant 120- gun ship down to a barge. You give up your coach-and-six for a wheelbarrow. Your monument... more enduring than the pyramids is given up for a pine slab at the head of your grave." Though the wavering businessman offered further doubts, he responded to such fighting metaphors suggesting progress, modernity, and permanence. He nodded acquiescence when Jewett exhorted him to leave insignificant schools to men of small means and smaller hearts. "Do something, I beg you, worthy of the ample fortune Providence has given you, and worthy of Him who gave it."

The college for women was visualized as the equal or even the superior of anything Europe could offer, and Vassar sent Jewett abroad for eight months to study "systems of female education prevailing in the most enlightened countries of Europe" and report to -him and the newly appointed board of trustees, who voted their President, Jewett, full salary, $2000 a year, but disallowed him any money for traveling expenses.

In the ensuing report, Jewett stressed the importance of high academic standards, a good library, the best apparatus, a well-chosen art gallery, a distinguished faculty, large endowment, and a full provision for a refined domestic life includiog nurses, matrons, a kitchen, and a janitor.

As chairman of the board of trustees, Vassar scrutinized every activity concerned with buildings, grounds, books, trees, gardens, disciplinary rules, and personnel. The brewer and the clergyman worked for a time in almost perfect harmony.

Uneasy lies the head that wears a crown. With the strength of passionate conviction, to which some ill temper was added because of nervous fatigue, Jewett pressed for the immediate opening of college, the immediate adoption of his curriculum, and the immediate appointment of the faculty. The trustees and Vassar opposed such haste.

Harassed beyond his strength, on the verge of a physical and mental breakdown, stung by personal and official insults, Jewett lost his usual gentle, persuasive, and cultivated forbearance. He wrote a letter to a trustee and sent five copies of it to close friends of the trustees. It described the issues, outlined the attacks on him, and described Vassar as a man vacillating, childish, and fickle.

The letter fell into Vassar's hands. Grievously hurt, he refused to have any more dealings with Jewett and requested his resignation. After full consideration, Jewett in a courteous letter devoid of bitterness admitted his error and resigned after only four years as President (1861-1864).

ON the side of underprivileged people even as a college student, Oren B. Cheney chose to resign from Brown and enter Dartmouth in the Class of 1839 because Hanover had the reputation of being more broad-minded about antislavery sentiments. Hanover gave him an opportunity daily to visit Indians, men, women, and children encamped for months at a time in the Vale of Tempe and to teach them on a no-pay basis. Weekends at Dartmouth he used to walk 20 miles round trip to Grantham to lead Saturday evening prayer meetings, conduct Sunday School, and teach singing because the congregation was too poor to pay a regular pastor.

Hanover and indeed all New England was in the midst of the abolition movement with pros and cons often expressed with more violence than those inherent in soft-spoken and academic arguments. William Lloyd Garrison was mobbed in Boston when Cheney entered Dartmouth, but violence was not limited to big cities and important men. Dartmouth upheld its reputation for openmindedness, previously established by the admission of Edward Mitchell, a Negro, Class of 1828, by accepting its second Negro in the Class of 1841, Thomas Paul, who merited the College's faith in him by becoming a teacher in Boston, Providence, and Albany. Feeling, nonetheless, was strong in the state against Negroes. When Cheney as a student was teaching school in Canaan during a winter term, upholders of slavery, hearing that Negroes were attending it, hitched some oxen to the school building and goaded them into pulling it into a swamp a mile away.

Outspoken in sermons, Cheney in West Lebanon, Maine, made some derogatory remarks about slavery which so outraged a member of the congregation that he ostentatiously left the church. When recalling the incident, Cheney would smile and add, "The man was a good Christian gentleman. He's dead now - and in Heaven."

But mostly Cheney was grimly serious. A mystic, he talked to God and God understood, and God talked to Cheney and Cheney understood. In Boston when he saw a captured Negro being returned to Southern slavery, Cheney burst out: "Oh, Thou great and mighty God! ... Why dost Thou not in anger stretch out Thine hand and let Thy winds blow, Thy tempest rise, the ocean rock in fury, Thy thunderbolts crash and all on board one only except - go to the lowest bottom! Why? Because Thou art slow to anger and waitest to be gracious!"

Cheney's eloquence may not have changed Massachusetts much, but his faith changed Maine. Bates College was founded in 1864 because Cheney knew that in a moment of crisis God had singled him out as his agent. The occasion was the burning of Parsonfield Seminary in 1854. Upset because he had studied, preached, taught, and lived his early married life there, Cheney was even more upset because bright boys might be lost for the ministry. Suddenly he heard a voice speak to his inmost being, "Do this work for Me." Such a command involved a supreme sacrifice, giving up the ministry, and Cheney prayed for guidance. God spoke to him a second time, and Cheney answered, "Here am I, Lord, to do Thy will."

God's will was for Cheney to raise money and to found in 1854 Maine State Seminary with Cheney as Principal, six teachers, and 137 students. Five years later he had another beatific vision. A committee of students with tears in their eyes begged the trustees that a college course be given. Cheney moved that the request be granted, but it was voted down. Refusing to admit defeat, he wrote: "We must have a college or in fifty years we shall cease to exist as a denomination. As if a trumpet called me, I started up. I believe it was the call of God. I did not desire to enter upon this work - God is my witness; I knew well the prejudices and the cold looks and the hard thrusts I must receive, but I did enter upon it for Jesus' sake and for the sake of the denomination I love."

Primarily a builder, Cheney fought for educational money most of his life. One successful drive was through Maine Sunday schools. He asked each child to give a dollar. In came letters such as: "Mr. Cheney Dear Sir, I am a little girl eight years old, and sister Em six —we send you one dollar each which we have earned drying apples as the Child offaring [sic] for Maine State Seminary."

Personal solicitation, correspondence, newspaper and magazine articles brought Cheney to the verge of success, but then came the financial depressions of 1857 and 1858 just as the school was about to open. Cheney could borrow only at 12%. With $4000 bank paper due and no funds, he proposed to sell his house and reimburse his friends who had lent him money. Because he had "a conscience void of offense towards God and man, and that is wealth enough for my poor, short life," he wrote, he could face complete poverty. Fighting on, nonetheless, he infused others with his battle cry. "A nation, like a Christian, lives by faith." The faith produced the good works. Burning appeals from ministers, parents, teachers, and friends were so successful that the $24,000 was raised and the Seminary survived.

Then the Seminary was not enough. It must grow to college stature if Cheney's ideals were to be realized. So strenuous and widespread was opposition that Cheney felt as though he were all alone in the world with his only companion a great purpose. Fortunately Benjamin E. Bates of Boston, Cheney inspired, promised $50,000 if another $50,000 could be raised. Malicious rumor circulated that Bates had promised no such sum. Stung by such pettiness, Bates determined to withdraw, but Cheney pleaded with such eloquence for reconsideration that Bates, shaking his hand, cried, "I will stand by you, Dr. Cheney."

When Bates was founded, it was coeducational, a carry-over from the seminary, but the men wanted the higher education only for themselves and showed such dislike of co-eds that all withdrew except Mary W. Mitchell, who had worked in a mill to earn enough to pay off the family farm mortgage and provide the wherewithal for her own education. Not only did President Cheney back her but he requested a special Mitchell scholarship from the Governor, who acquiesced. Mary politely declined, however, for she wanted to be independent with the money she had earned herself the hard way. Because of her, Bates is still co-educational.

With a beard confined to chin and cheeks, with small eyeglasses metal rimmed, President Cheney was a severe disciplinarian, stern with his students about language and even sterner with himself. Violent in his denunciation of alcohol, he required a pledge of absolute abstinence from each entering student. Aged 87, dying, he had relapsed into apparent unconsciousness, but was roused when the nurse attempted to give him a little brandy and water. According to his wife, he seemed called back from the other world to give one final protest against the intoxicants which he had never touched.

As builder, Cheney founded or helped others to found Parsonfield Seminary, Lebanon Academy, Maine State Seminary, Maine Central Institute, Storer College, and Cobb Divinity School, but Bates was his most significant achievement.

THAT Nathan J. Morrison, Dartmouth 1853, should have become a Congregational minister, a classics professor, a college president, and founder of a college is remarkable because until twenty he had the educational advantages only of a district school in Franklin, N. H., four months a year. Ordained in the Congregational Church at 29, at 31 he taught Greek and Latin at Olivet College.

Of Scotch-Irish lineage, slim and dark, delighting in good clothes, Morrison won favor in the wilderness village of Michigan. Though persons considered him visionary, he had such ebullience, confidence, and drive that what he started he finished successfully. He was a happy combination of the austerity, stoicism, and reticence of New England educators with the energy, fire, and optimism of Western pioneers. During his 13 years of service as Professor of Languages, Librarian, Acting President, and President, he virtually refounded the college.

Olivet was too small to contain so creative a spirit. Though immersed in Olivet affairs, Morrison became interested in Springfield, Missouri, a growing town occupying a strategic point 240 miles southwest of St. Louis and lying in the march of New England culture towards the southwest. After sketching educational plans, he founded there Drury College in 1874. Mostly by personal solicitation, as President he raised an endowment of $400,000, erected six buildings, planned courses of study, selected a faculty, collected a library of 29,000 volumes and attracted a student body of 300, a success hardly to be paralleled in the annals of western colleges. He helped it weather the panic of 1873 and the subsequent depression smoothed over local animosity and misapprehension about college goals, and faced courageously a crisis when the best college building burned down.

Morrison was a moral force, and he spoke out with all the conviction of an Old Testament prophet. In a sermon to a graduating class, "Decay of the Peopie's Sense of Duty," he found proof of moral degeneracy in prevalent irreverence. Children defy their parents. Husbands and wives repudiate their marriage vows. Courts and juries are swayed by popular feeling. Each citizen thinks himself better than his neighbor. Envying and emulating the rich, common laborers "hanker after sumptuous living and riding in carriages." The commercial spirit corrupts political life. Contracts are not honored but dodged. Atheistic opinions are rapidly spreading. Literature is poisoned. Insisting too strenuously on human rights, the platform, pulpit, and press keep silent about the duties of men. What was needed, according to Morrison, was a new emphasis on "the homely duties of chastity, honesty, fidelity to contracts, sobriety, and industry."

Never a man to rest on his laurels, even at the age of 60, Morrison resigned the presidency of Drury in 1888 and accepted the chairmanship of the Department of Philosophy at Marietta College from its President, John Eaton, Dartmouth 1854. Here again Morrison had more energy than his position could consume during seven years of teaching Philosophy, Psychology, Ethics, and Christian Apologetics. He became interested in the project of raising Fairmont Institute in Wichita to the rank of a college. In this enterprise he was again successful. In 1896 he became its president, and with unflagging energy he continued his academic and executive struggles for twelve years against financial reverses following expansion until his death at 79 in 1907.

Devoted and vehement, these eight clergymen-presidents believed that young Americans should be given religious and ethical instruction not at fixed times, but continually. Every subject should be per- meated with Christian piety and moral order. The disciplines imposed then on faculty and student body may seem benighted to modern professors and undergraduates. Grounded in the wisdom of Greek, Latin, and especially Hebrew learning, these stoical first presidents of another era were of such ethical stature that they commanded not only respect but also admiration and loyalty.

Joseph McKeen, Class of 1774First President of Bowdoin

Ebenezer Porter, Class of 1792First President of Andover Theological

Zephaniah S. Moore, Class of 1793First President of Amherst

Philander Chase, Class of 1796First President of Kenyon and Jubilee

Milo P. Jewett, Class of 1828First President of Vassar

Oren B. Cheney, Class of 1839First President of Bates

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureTwelve Hours and Their Aftermath: The Student Seizure of Parkhurst Hall

June 1969 By C.E.W. -

Feature

FeatureThe Class Officers Weekend

June 1969 -

Feature

FeatureFOUR PROFESSORS WHO ARE RETIRING

June 1969 -

Feature

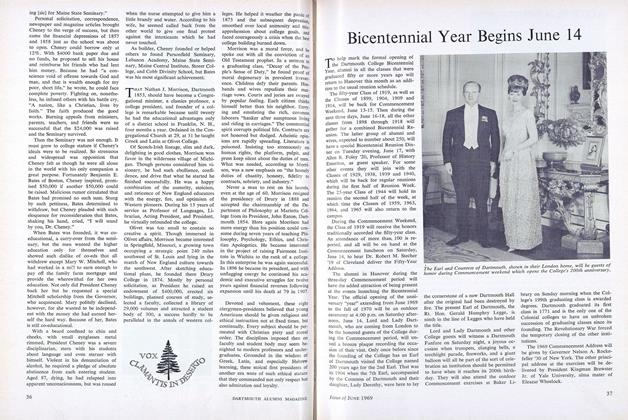

FeatureBicentennial Year Begins June 14

June 1969 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Awards

June 1969 -

Article

ArticleThe Faculty

June 1969 By WILLIAM R. MEYER

John Hurd '21

-

Books

BooksDIDEROT, THE TESTING YEARS,

July 1957 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Article

Article"Janssen Plan for Peace"

OCTOBER 1958 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksAMAZING BUT TRUE ANIMALS.

JANUARY 1964 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksWHAT THE OLD-TIMER SAID: TO THE FELLER FROM DOWN-COUNTRY AND EVEN TO HIS NEIGHBOR—WHEN HE HAD IT COMING

JULY 1971 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksCARTAS SOBRE EL ANFITEATRO TARRACONENSE.

JUNE 1972 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksA GUIDE TO BEHAVIORAL ANALYSIS AND THERAPY.

DECEMBER 1972 By JOHN HURD '21

Features

-

Cover Story

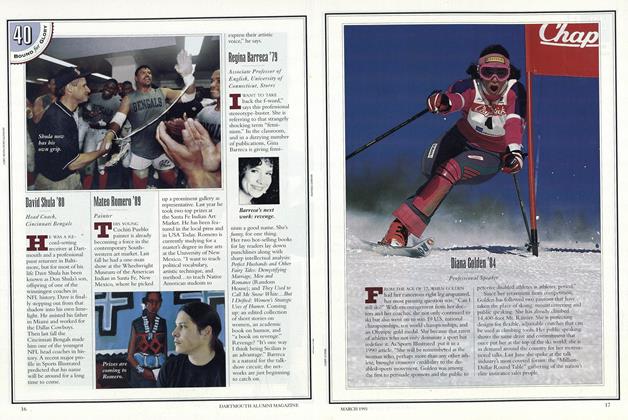

Cover StoryMateo Romero '89

March 1993 -

Feature

FeatureMICHAEL BRONSKI

Sept/Oct 2010 -

Feature

FeatureThe American Dream

JANUARY 1972 By A.T.G. -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth De Gustibus: More Food for Thought

December 1974 By JOAN L. HIER -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

May/June 2012 By SPORTING NEWS VIA GETTY IMAGES -

Feature

FeatureHeeding the Beat of a Different Drummer

SEPTEMBER 1987 By Teri Allbright