An account, based on the College Collections, of incidents in the Dartmouth life of the immortal statesman, who died 100 years ago this month

IN February of 1797 in the town of Salisbury, New Hampshire, Ebenezer Webster and his son Daniel climbed into a sleigh and set out for Boscawen, some halfdozen miles away. The purpose of their journey was to place the boy under the instruction of "that most benevolent and excellent man," the Rev. Samuel Wood.

It was as they were ascending a hill through the deep snow that the father first made known his intention of sending the son to college. So great was the impression made upon his mind, Daniel Webster could in later life remember "the very hill" and the surge of emotion he had experienced at the time.

"The very idea thrilled my whole frame. He said he lived but for his children, and if I would do all I could for myself, he would do what he could for me. I remember that I was quite overcome, and my head grew dizzy. The thing appeared to me so high, and the expense and sacrifice that it was to cost my father, so great, I could only press his hands and shed tears."

The youngest of Ebenezer Webster's sons, Daniel was of frail constitution, thought unlikely to allow him "to pursue robust occupation." This, together with his keenness of mind and fondness for reading, was probably the deciding factor in singling him out for this unexpected opportunity of collegiate study.

Of actual preparation for college Webster had very little. He, with the other children, had attended the irregular and "sufficiently indifferent" instruction of the country schools, where only reading and writing were taught, and in the former, he recalls, "I generally could perform better than the teacher." Late in May, 1796, he had entered Exeter Academy, remaining little more than six months, and not completely happy among boys "who had seen so much more, and appeared to know so much more than I did." There he studied English grammar, writing, and arithmetic and began Latin.

At the end of the fall term he had returned home to Salisbury and taken up teaching a district school attended by boys and girls some of them older than himself. It was probably through the intervention of the Rev. Samuel Wood (Dartmouth 1779) that Daniel Webster was rescued from his pedagogical career.

Between February and August, 1797, the Reverend Mr. Wood and his pupil labored at the task of fitting Daniel to enter Dartmouth, requiring that he "be versed in Virgil, Cicero's Select Orations, the Greek Testament, be able accurately to translate English into Latin; and also understand the fundamental rules of Arithmetic."

In August, only fifteen months from the time of his beginning at Exeter, he rode to Hanover to be examined by the "executive authority." He was, by his own avowal, "miserably prepared, both in Latin and Greek."

Slender, thin-cheeked, with high, prominent cheek bones and "all eyes," his complexion was even then of that swarthy hue that marked him throughout life as "Black Dan." On the first Sabbath after his admission, sitting in the gallery of the meeting house, he was taken by one of the townspeople to be an aborigine from the Indian Charity School.

In his Life and Memorials of DanielWebster, General Lyman preserves a story about young Webster setting out for "his first visit at Hanover and his examination," garbed in "a new suit of blue clothing" made for him by "a near neighbor, who was engaged in the domestic manufacture of clothes." Traveling on horseback, "he encountered a violent storm, which lasted two days, raised a flood, carried away bridges, [and] delayed his arrival."

When, drenched with rain, he finally dismounted on the College Plain, "the faculty for his examination was in session, and his presence was required immediately." He presented himself post-haste, and it appears that it was not until he had finally gone to his room that he realized "the soaking rain had started the color in his new suit, and that from head to foot, under clothing, skin and all, he was as blue as an indigo-bag."

Another "Blue Dan" story, however, differing in every particular, is recorded by Webster's aspirant Boswell, Peter Harvey, giving Mr. Webster as his source and stating that the incident occurred while Dan'l was returning to Dartmouth after being "at home from college on a vacation in the winter time," rather than at the beginning of his college career.

THE faculty under whose tutelage Webster came in 1797 was composed of three men: John Wheelock, formal and aloof, devoted to his books, and respected (though not revered) by the students; John Smith, a productive scholar, "the best linguist in New England," but a man of monumental dullness"; and Bezaleel Woodward, "in everything the reverse of Professor Smith and President Wheelock," sociable and practical, not scholastic in appearance or manners, and most popular with the students.

To assist the "executive authority" there was each year a tutor, usually a recent graduate, who apparently directed much, if not most, of the recitation work of the scholars.

Although the staff was small, the academic ground was admirably covered. "Clothespins" Richardson once wryly remarked, "The extent of the wisdom of the teachers reminds one of Italian versatility in the time of Leonardo." In addition to being President, Wheelock was professor of civil and ecclesiastical history and instructor in natural and political law, and he conducted all the work of the senior class. Smith held the professorship in Greek, Latin, Hebrew and Oriental languages, and served as librarian. Woodward, the senior member, was treasurer and professor of mathematics and natural philosophy. All three were trustees.

On beginning his academic career, Webster as a freshman would have studied "the Latin and Greek Classics, Arithmetic, English Grammar, Rhetoric & the Elements of Criticism." The regulations of the day also provided that "the members of the classes in rotation shall declaim before the officers in the chapel on every Wednesday at two o'clock in the afternoon such and so many in a day as the government from time to time order." And once a month, following these declamations, the seniors were required to "hold a forensic disputation."

Not only did Daniel Webster enter Dartmouth with unimpressive preparation in the classic languages, but, it must be recorded, he arrived with a very unpromising background for any kind of accomplishment in these "Wednesday rhetoricals."

At Exeter he had been utterly unable to "make a declamation." He just "could not speak before the school." Joseph Stevens Buckminster, then acting in the place of the indisposed headmaster, befriended the awkward country boy and tried valiantly to bolster his courage and determination, but to no avail.

"The kind and excellent Buckminster sought, especially, to persuade me to perform ... like the other boys, but I could not do it. Many a piece did I commit to memory, and recite and rehearse, in my own room, over and over again; yet when the day came, when the school collected to hear declamations, when my name was called, and I saw all eyes turned to my seat, I could not raise myself from it.

"Sometimes the instructors frowned, sometimes they smiled. Mr. Buckminster always pressed, and entreated, most winningly, that I would venture; but I could never command sufficient resolution. When the occasion was over, I went home and wept bitter tears of mortification."

It was doubtless largely a feeling of inferiority that caused his inability to perform. Of "uncultivated manners" and presenting a "country cut appearance," Webster was the object of ridicule from pupils superior in the matter of dress and in accomplishments of form rather than in intellect.

But he seems to have miraculously lost all semblance of this inhibition in college. His roommate for about one year, Aaron Loveland, is reported to have declared, "He was very ambitious in college from the first and took every opportunity to make himself conspicuous. He had unbounded self-confidence, seemed to feel that a good deal belonged to him..."

Webster unquestionably developed his oratorical talents during his undergraduate years. His intellectual promise had perhaps been recognized by his early teachers at Exeter and Boscawen, but not until he entered "classic Dartmouth's college halls" had he shown any symptoms of developing into an orator. It was on Hanover Plain that he found conditions both of opportunity and stimulus rightly attuned to this development.

On November 7, 1797, the United Fraternity "increased its number by the accesion" of Freshman Daniel Webster. It was the beginning of an association that very probably had much to do with his advancement.

The "Fraters" met weekly on Tuesdays, when there were "exhibited" two orations, two dissertations, and one written and two extemporaneous disputes. The records indicate a lively body, which "agitated" such questions as: Is the aggregate of misery as great in other animals as in Man? Have the savages as much reason to call us barbarians, as we have them? Has the invention of the art of printing been of greater benefit than that of gun-powder? Would it be profitable for students to attend to learning the art of dancing?

In most cases the clerk has dutifully noted the well-considered conclusions reached by the disputants. No answer, however, is recorded-be it be said with regret—to the question: Which is more eligible for a wife a widow or an old-maid?

Webster's abilities were evidently well appreciated by the Fraternity, for he held successively all the important offices in the society including the presidency, and on occasion took prominent part in its public "exhibitions." In his senior year he delivered the United Fraternity oration on the day before his Commencement. This piece, on "the Influence of Opinion," was preserved in the archives of the society, but the volume containing it disappeared many years ago-or, as a Dartmouth professor once eloquently put it, it was purloined by some literary thief, who ought to be disfranchised from the republic of letters."

That venerable professor, now many years dead, would certainly be no less gratified than are the living, could he know that eight years ago the priceless volume turned up, was bought by a Dartmouth man, presented to the College, and is now back among the other surviving records of the society.

ASIDE from his fraternal activities, WebXV ster was, with his classmates, pursuing a curriculum "as rigid, and irrevocable as fate." He was not, as has sometimes been claimed, the first scholar in his class. The meagerness of his preparation showed itself in his recitation work, especially his weakness in the classics which then formed a large part of the first years of the curriculum. He was, however, "particularly industrious," and considered "remarkable for his steady habits, his intense application to study, and his punctual attendance upon the prescribed exercises." He read a great deal, "more than any one of his classmates," particularly history, literature, and philosophy.

His classmate Thomas Merrill, fifty years after their graduation, wrote:

Webster did not develope in College any remarkable traits of character till he came to the English branches-particularly the belles lettres department. In his Junior year he took, compared with his class, a higher stand, and in writing & extemporaneous speaking he decidedly outstripped them all. But it is doubtful whether this could be said of him in any other departments, and I have had decisive reason within a year to suppose he would himself take this ground, should any one enquire of him.

Merrill's "decisive reason," was a letter written by Mr. Webster just a year before his death, saying in part:

I well remember that I did not keep up with you in the stated course of collegiate exercises. ... I indulged more in general reading, & my attainments, if I made any, were not such as told for much in the recitation room. After leaving college, I "caught up," as the boys say, pretty well in Latin: but, in college, & afterwards, I left Greek to Loveland, & mathematics to Shattuck.

Webster at this period, as in later life, was credited with a very retentive memory. "He read with great rapidity and remembered all." He himself is quoted as once having told a friend:

... so much as I read, I made my own. When a half hour, or an hour at most was expired, I closed ray book and thought it all over. If there was anything particularly interesting to me, either in sentiment or language, I endeavored to recal[l] and lay it up in my memory, and commonly could effect my object. Then if, in debate or conversation afterward, any subject came up on which I had read something; I could talk very learnedly so far as I had read, and then was very careful to stop. Great credit was then given me for knowledge of the whole subject, when in truth my whole stock was expended, and I could not have advanced one step further.

His method of preparing for "declamations" is described by a classmate, who recalls that "when he had to speak at two o'clock, he would begin to write after dinner; and when the bell rung he would fold his paper, put it in his pocket, and go and speak with great ease." This same source reports that once while writing with the windows open, a sudden gust of wind carried away his paper "and the last it was seen, it was going over the meeting house." Webster, however, was completely unruffled and went off and spoke the piece as if it had been carefully put to memory.

The college laws of the period governing student conduct were numerous and detailed, and, writes L. B. Richardson, "As might have been expected, the undergraduate body rose to the occasion and gave the 'executive authority' abundant practice in the administration of discipline." Daniel Webster, however, seems not to have made any contributions toward improving the faculty's proficiency in this art. He was, we are told, "a strict observer of order" and "always viewed with conempt disorderly conduct." "He never engaged in college disturbances," says one."I should as soon have expected [this from] John Wheelock the President as Daniel Webster."

His dress in his early college days was similar to that of the other country boys, perhaps even careless. But in his junior year his classmates perceived a marked change in his appearance. Thenceforth he dressed much better than the average member of his class. It has been suggested that this may have coincided with new-found social interests in certain Hanover misses, and there is some evidence to support this view. The cause, however, would have lain in improved economic means.

Webster was noted by his contemporaries for his high religious character at a time when the College was experiencing a period of great irreligion among the undergraduates. Loveland felt that "Dan was rough and awkward, very decidedly." He was popular with his classmates, but, as Bingham states, "not intimate with many." Roswell Shurtleff commented, "He had no collision with any one, nor appeared to enter the concerns of others, but emphatically minded his own business."

On August 27, 1799, there was issued the first number of the Dartmouth Gazette. It was not an undergraduate publication, but Webster was associated with it from the outset, both as contributor and editor or superintendent. Concerning this activity he once wrote,

I even paid my board, for a year, by superintending a little weekly newspaper, and making selections for it, from books of literature, and from contemporary publications. I suppose I sometimes wrote a foolish paragraph myself.

Of his time as a journalist little more is known, excepting that some at least of the "foolish paragraphs" to which he alludes were signed with the pseudonym Icarus. The files of the Dartmouth Gazette for his undergraduate period contain thirteen pieces bearing this signature, and treating such themes as "Hope," "Fear,"

"Spring," and "Winter." Icarus wrote in prose and verse, often using both in the same piece, and he was much concerned with political topics.

The opening sentence in "Charity" is perhaps fairly representative of his journalistic prose style:

If there is a virtue, which ennobles and dignifies Man,-if there is one, that assuages the boisterous passions of his soul, prepares it for the reception of heavenly enjoyments, and assimilates him to celestial beings, it is Charity.

One biographer has with justice written, "in respect to most of his rhymes that remain ... there is nothing that can, critically speaking, be dignified by the name of poetry." There is, however, a report of a poem read by Webster during his junior year which speaks highly of his poetic ability. The poem was about "a battle between an English and a French ship-ofwar, in which the latter was sunk." It "held the professor and the class in apparent amazement. I almost shudder," states one who heard it, "as, fifty-four years after, I seem to see the French ship go down, and to hear her cannon continue to roar till she is absolutely submerged."

WITHOUT doubt the most significant event of Daniel Webster's entire college career was his oration before the citizens of Hanover on the 4th of July, 1800. Much of what the 19-year-old junior said was florid and bombastic and typical of the ordinary patriotic orator of the day. Yet there are passages in the speech that anticipate in language, tone and sentiment his later brilliance of oratorical style.

One finds, for example, such passages as:

We behold a feeble band of colonists, engaged in the arduous undertaking of a new settlement in the wilds of North America. Their civil liberty being mutilated, and the enjoyment of their religious sentiments denied them in the land that gave them birth, they fled their country, they braved the dangers of the then almost unnavigated ocean, and sought on the other side of the globe an asylum from the iron grasp of tyranny and the more intolerable scourge of ecclesiastical persecution.

In another instance he touches on a subject that was to be for him a life-long issue:

... in the adoption of our present system of jurisprudence, we see the powers necessary for government, voluntarily springing from the people, their only proper origin, and directed to the public good, their only proper object.

The Dartmouth Gazette reported that the speech "would have done honor to gray-headed patriotism, and crowned with new laurels the most celebrated orators of our country." Mr. Webster, however, was evidently more affected by another notice. Only five weeks prior to his death he is reported as having recalled:

When I was a young man, a student in college, I delivered a fourth of July oration. My friends thought so well of it that they requested a copy for the press. It was printed, and I have a copy.... Joseph Dennie, a writer of great reputation at that time, wrote a review in a literary paper which he then edited. He praised parts of the oration as vigorous and eloquent; but other parts he criticised severely, and said they were mere emptiness. I thoughthis criticism was just; and I resolved that whatever else should be said of my style, from that time forth there should be no emptiness in it.

In 1801, just a short time before the class was to be graduated, one of their number, Ephraim Simonds, died. The student body, and particularly his own classmates and his brethren of the United Fraternity, were deeply moved by Simonds' death. Preparations were made for his funeral, and Daniel Webster was selected to pronounce the eulogy, which was subsequently printed.

The emotional circumstances surrounding the occasion were a heavy burden for the young eulogist, and he rarely rose to any heights of expression, finding it, as he advised his listeners, "unnatural to aim at brilliant imagery, or elegant diction, 'when grief sits heavy at the heart.' "

Mr. Webster in later life was always a severe critic of his collegiate efforts, believing them in "bad taste" and of a period when he had not yet learned that "all true power in writing is in the idea, not in the style." In this connection, George Ticknor has preserved an amusing anecdote concerning the Simonds eulogy. While dining with Mr. Webster in 1820, Ticknor mentioned that he had recently found a copy of the pamphlet. The statesman "looked surprised, and turned suddenly and rather sternly" to his guest,

I thought till lately that, as only a few copies of it were printed, they must all have been destroyed long ago; but the other day Bean, who was in college with me, told me he had one. It flashed through my mind that it must have been the last copy in the world, and that if he had it in his pocket it would be worth while to kill him to destroy it from the face of the earth. So I recommended you not to bring your copy where I am.

It has sometimes been stated that Daniel Webster intended to pursue a career in medicine, basing this deduction on the fact that he is listed as a former student in the Dartmouth Medical School. The conclusion cannot, however, be justly drawn from the evidence available, and it really is highly improbable that such was his intent.

Of the 32 men in the Class of 1801, no fewer than 19, Webster among them, are today listed as non-graduates of the School. To this there can be little objection, for they were Nathan Smith's pupils, and he was the Medical School. But that many were seriously bent on following the profession of Hippocrates is doubtful, if only because but three ever became physicians. And there is more than casual evidence to suggest that Webster and his fellows were chiefly interested in the Chemistry-Materia Medica lectures only.

OF all the problems connected with his undergraduate life which confound the student of Webster, none is more discouraging or withholds itself from solution more tenaciously than where it was he lived while in college.

George Farrar, Class of 1800, in a letter to Prof. E. D. Sanborn written in November, 1852, is quoted as having declared. "Mr. Webster, Freeborn Adams, my brother William and myself, roomed in my father's house, during the first two years of his college course." It is probable that the house, as one authority stated, "survives, at least in part" in the dwelling just south of the present post office and now called "Webster Lodge."

The Treasurer's records, however, seem to contradict the Farrar statement. In neither of the years in question were all four students recorded as having made the same arrangements for their rooms. The ledger entries indicate that one paid no rent to the College at all in either year, another was charged fees for unoccupied college rooms during both years, the third paid no rent one year but did the second, while Webster paid rent to the College both of these years.

On North Main Street by the greenhouse stands the little house known as "Webster Cottage." At the time Dan'l was in college it was the home of Mrs. Sylvanus Ripley. Its claim to having once housed Daniel Webster, probably in his senior year, is largely based on a memorandum set down in 1896 by Miss Lucy Jane Mc- Murphy. She writes that she can "well remember" back in the forties or fifties,

Mr. Wm. Dewey... bringing in one morning a Dogeared Manuscript Book of his to read to my Aunt what he had written in it about this building 10t.... He told who built the house.... He said Daniel Webster roomed here. He knew him well when he was in Coll[ege]. I think he said he roomed in the South Chamber.

Dewey was a careful observer with an historical bent and accustomed to putting things down on paper. Much information on the early history of Hanover has been derived from his jottings. His statement is not the only evidence in favor of the authenticity of the "Webster Cottage claim, but it is the most specific and convincing.

The late L. B. Richardson in his history of the College states that "evidence which has come to light in the course of this investigation shows with certainty that in his sophomore year he occupied room No. 6 (north end of the first floor) of Dartmouth Hall, although the same evidence puzzles us by indicating that in his junior year he did not room in that structure at all" (although he did pay rent to the Colkge).

There is also a suggestion that during the junior year he and Aaron Loveland lived together in the Dewey household. Tradition has it that in his senior year he lived in room No. 1 of Dartmouth Hall. And still another source reports that "a part of the time at least" he roomed with the Bissell family.

Webster's words, "The past at least is secure," take on ironical meaning to those who would know more of his college years, particularly of where it was he hung his hat. Recent investigators have tended, pending discovery of less equivocal evidence, to lend credence to the "Webster Cottage" claim and question strongly that of "Webster Lodge."

AT his graduation in 1801, Daniel Webster took no part in the speaking exercises, due, as he later put it, to "some difficulties, hæc non meminisse juvat."

Under the system then observed, the faculty made the first three commencement appointments: the Salutatory, Philosophical, and Greek orations. The recipient of the fourth honor, the Valedictory, was normally selected by the seniors themselves by means of an election within the class. The students apparently came to consider the Valedictory as the most important appointment, although at that time the Salutatory was actually the highest rank. The elections were often spirited contests, and sometimes were characterized by bitter rivalry.

The "difficulties" connected with Webster's commencement grew out of a decision on the part of the "executive authority" to avoid quarrels by taking the choice out of the hands of the class and to appoint the Valedictorian along with the other speakers.

A seemingly authoritative source reports that when the appointments were announced by the President, the Salutatory oration in Latin was assigned to Thomas Merrill, and the second appointment was tendered to Webster. (It is reported that he was to deliver an oration on the fine arts or give a poem.) The faculty, perhaps, believed that they were doing him considerable honor in the appointment. But ster and many of his classmates are said to have felt that he should have had the Valedictory, and a heated controversy ensued in which quite a number of men threatened to take their leave of the College.

The dispute seems to have been largely a fraternal, rather than a personal matter, but one in which Webster was the central figure. The members of the United Fraternity "considered themselves sorely aggrieved," feeling that favoritism was being shown toward their rivals, the Social Friends.

That this resentment of "Social ascendency in the Faculty" was not a condition of momentary duration is attested by a letter written by an undergraduate to Webster four years after he had taken his degree. Addressing him as former "head of the opposers" of the authority, and expressing gratification at seeing "one who is worthy of honors hold them in contempt, because they are not bestowed according to merit," the writer declares.

... since every one who has any acquaintance with the government of this College knows that they confer all their favors on cringing, insignificant sycophants, it is a real disgrace to a schollar to be distinguished with one of the first appointments Those [to] whom I have reference as being neglected belong to the Fraternity.

The tempers of the "Fraters" ultimately cooled and commencement day found all, save one seemingly unforgiving senior who had already departed, receiving their degrees with the rest of the class. None of them, however, took any part in the "literary performances."

There is, as President Bartlett put it, "one falsehood concerning the graduation so widely circulated that it perhaps will never die till all the foolish and the idlers are dead." It is the oft-repeated statement that Webster, still angry over the assignment of commencement parts, tore into pieces his newly received diploma.

The complete fallacy of the claim is borne out by ample testimony. Many years after the supposed occurrence one classmate said the tale was "altogether news to me," and felt that it was "scarcely to be credited." Elihu Smith stated that the report that Webster destroyed his diploma was untrue, and said, "I stood by his side when he received it with a graceful bow." And Mr. Webster himself, "when his attention was specifically called to it," is reported as having declared that there was "not a word of truth or semblance of it in the whole story."

Such were some of the events of Daniel Webster's college life. What his four years on Hanover Plain did for him can be judged by the part they played in fitting him for a career of brilliance both in the courts of law and the halls of Congress, in diplomatic chambers and, perhaps most of all, upon the public platform.

What Dartmouth meant to Webster he himself demonstrated, not only by his eforts in the fight to preserve her independence, but through a life-long devotion to her causes and interests. "I feel, he once said of the College, "that I owe it a debt, which may be acknowledged indeed, but not repaid."

A likeness of young Webster, from a miniature done shortly after his graduation.

DARTMOUTH COLLEGE as it appeared when Daniel Webster was an undergraduate. This drawing was made by George Ticknor, famous American scholar, as a sophomore in 1803.

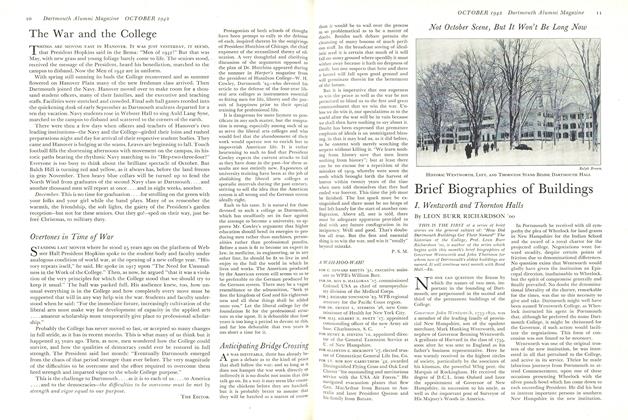

THE MINUTES OF PHI BETA KAPPA, to which Webster was elected, include these signed pages written in his own hand when he served as secretary pro tern during his senior year.

JUST EXACTLY WHERE Webster roomed as an undergraduate is not known for certain. The claim that he lived in "Webster Cottage" (left) his senior year is pretiy well authenticated. The story that he roomed in "Webster Lodge" (right) in freshman and sophomore years is not supported by college records.

GILBERT STUART'S WEBSTER: Outstanding in the College's collection of Webster portraits, the finest in existence, is this copy of Stuart's 1825 painting. The head at least was copied by Stuart himself and the rest by his daughter Jane. The painting was given to Dartmouth by Edwin Webster Sanborn, whose mother was the niece of Daniel Webster, for whom the copy was made.

PAINTED BY JOHN POPE, this portrait was considered by Webster's relations to be the best likeness of the great statesman as he appeared in later life. It was given to Dartmouth in 1912 by Edward Tuck, who bought it from the son of H. B. Goodyear, the industrialist, who commissioned Pope to do the portrait.

THE FAMOUS "BLACK DAN" PORTRAIT by Franc's Alexander is one of four honoring the College's legal counsel in the Dartmouth College Case. Dr. George C. Shattuck presen ed this portrait of Webster in 1836 and at that time also gave those of Joseph Hopkinson, Jeremiah Mason and Jeremiah Smith.

PAINTED IN 1845 by Chester Harding, this famous profile portray shows the majesty of Webster's massive brow and powerful, deep-set eyes. It has been termed "the most human' portrait of Webster. Dartmouth received it by bequest of Charles Woodbury.

DANIEL WEBSTER '53, Dartmouth senior from Colorado, holds the lea!her fire bucket said to have been used by his famous namesake as an undergraduate. By rule of the Trustees in 1796, each student was required to keep a bucket filled with water in his room in case of fire. This historic relic is now on display at Dick's House.

Webster Portraits in Dartmouth's Collection

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

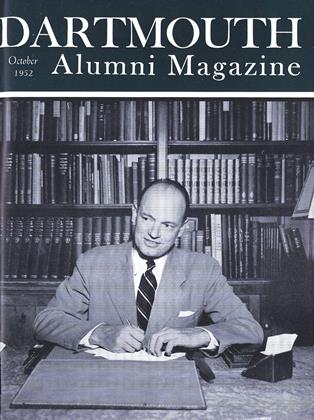

ArticleThe New Dean . . .

October 1952 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Men Active In the Big '52 Fight

October 1952 By C. E. W. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

October 1952 By ERNEST H. EARLEY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1905

October 1952 By GEORGE W. PUTNAM, GILBERT H. FALL -

Class Notes

Class Notes1948

October 1952 By FRANCIS R. DRURY JR., ROBERT L. MERRIAM -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921

October 1952 By REGINALD B. MINER, ROBERT M. MACDONALD

EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51

-

Feature

FeatureTHE MOCK-DUEL MURDER

April 1956 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51 -

Feature

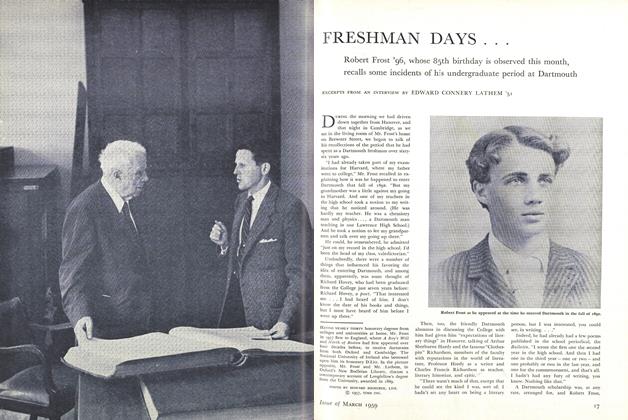

FeatureFRESHMAN DAYS...

MARCH 1959 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51 -

Feature

Feature...AND MANY DARTMOUTH YESTERDAYS

March 1962 By Edward Connery Lathem '51 -

Article

ArticleApril 1865: Jubilation and Grief

April 1962 By Edward Connery Lathem '51 -

Feature

FeatureAND MANY DARTMOUTH YESTERDAYS

FEBRUARY 1963 By Edward Connery Lathem '51 -

Feature

FeatureAs the Century Turned

JUNE 1963 By Edward Connery Lathem '51