DURING the past year Dartmouth's educational principles and practice have been the subject of special study by the Committee on Educational Policy, which has recently rendered its annual report to the Faculty. In the belief that alumni will be interested in the nature and work of the Committee, this article presents some information about its duties, its current activities, and its plans.

A year ago the Faculty reestablished its standing Committee on Educational Policy. For the four preceding years there had been no such committee, because the Faculty Council, instituted in 1947, was expected to take the lead in matters of educational policy. The Council, however, with its forty members, proved to be too large and too busy with other duties for detailed discussion of educational problems.

Discussion of this sort, based on study of the principles and operation of the educational process, is constantly necessary if a college is to remain alive to its duties and opportunities. For many years in the past, Dartmouth has studied itself. The most far-reaching result in recent times was the adoption by the Faculty in 1925 of the recommendations for a new curriculum presented by its Committee on Educational Policy under the chairmanship of the late Prof. L. B. Richardson '00. A thorough study of Dartmouth and other institutions had preceded these recommendations. Professor Richardson, with a leave of absence from regular teaching duties, had been asked by President Hopkins to investigate the purposes and methods of representative liberal arts colleges and to observe movements which might lead to their improvement. He visited nineteen institutions in this country, two in Canada, and twelve in England and Scotland. His book, A Studyof the Liberal College, published in 1924, embodies the results and is still an important educational document.

The curriculum adopted by the Dartmouth Faculty in 1925 is basically that now in effect: it leads to only one degree, A.B.; it has as its core a major study to which a student devotes about one quarter of the courses he takes in college; it requires a comprehensive examination as a final and essential part of the major; it provides for distribution and orientation in various fields of knowledge during the freshman and sophomore years; and it permits special work in the major for honors students. This general pattern is similar to that prevailing at many American liberal arts colleges, and the fact that it is still in effect at Dartmouth is a credit to the foresight and wisdom of the Faculty of 1925 rather than a suggestion that study of educational problems has stagnated since that time. Various relatively minor changes in the curriculum have been made: the content of the distributive and foreign language requirements has been altered; specific academic standings which the student is required to meet at the end of sophomore year and upon graduation have been established; the plan for Senior Fellows has been instituted; and the Great Issues course has been introduced as a requirement for seniors.

The Class of 1929 was the first to graduate under this curriculum, and all Dartmouth students since that time have benefited from a plan many of the principles of which may still be regarded as acceptable. Nevertheless, after a quarter of a century it is appropriate to under- take some general reappraisal of educational policy, and it is for this purpose that the Committee on Educational Policy was reestablished last fall. The Faculty vote stated that "it shall be the duty of the Committee on Educational Policy (1) to appraise continuously and, when appropriate, to propose changes in the educational policies and program of the College; and (2) to promote improvement in teaching effectiveness throughout the College. The Committee shall interpret these duties broadly."

This extensive assignment impressed us at the outset not only with the importance of our duties but also with the variety and multiplicity of the matters requiring consideration. Much of our time has been spent in feeling our way into the maze of problems before us. In response to a letter sent to each member of the Faculty asking for suggestions we received a number of ideas, and an early meeting with President Dickey gave us the benefit of his thoughts about our major tasks. We made a memorandum or agenda which consisted at that time of some forty items; it is longer now. A few examples may be cited: a restatement of Dartmouth's philosophy of liberal arts education; the relation of the undergraduate college to the Medical, Thayer, and Tuck Schools; the extent to which study of the curriculum must take account of present and future military service requirements; weaknesses in the present curriculum; the proper proportion of free electives, distributive requirements and concentration in a liberal arts curriculum; the number of courses a student should take; the effectiveness of our program for the first two years; the major; comprehensive examinations; honors work; the Great Issues course; methods of exempting exceptional students from some requirements; student advisory system; the relation of extracurricular activities to the educational process; and numerous questions relating to teaching methods. In short, we wish to consider basic questions pertaining to all parts and aspects of the educational process.

These and other topics have received preliminary examination during the past year as we have attempted to organize efficiently our approach to our duties. This general survey has been helpful, we believe, because it has enabled us to see clearly the interrelatedness of many aspects of undergraduate education. We are sure that an immediate attempt to solve what- ever one of these matters seemed at first to be most pressing would have been unwise. Our general discussions have made each of us feel better educated about education than a year ago, and we think this is a sound basis for future progress.

A few words more may be said concerning the formulation of a statement of Dartmouth's philosophy o£ liberal arts education. This is an enterprise which it would be profitable for anyone interested in the College to undertake. If he should do so, there is some chance that he would be satisfied with the result; there is less chance that he could persuade anyone else to accept it without alteration. If the statement is to be not only abstractly meaningful but also practically useful,, it must be expressed in terms general enough to cover all fhajor activities of the College and specific enough to have clear relevance to particular problems that call for solution. Thus, we all admire President Dickey's phrase "the free mind in men of good will" and his statement that "the liberal arts college alone of all institutions accepts as its unique responsibility the cultivation of a man possessing both the will ol a codperative spirit and the competence of a free mind." These are splendid statements of objectives, but our Committee is as much concerned with means as with ends, or rather, with the adaptation of means to ends, and for this purpose we have felt the desirability of defining in more specific terms the function of liberal arts education at Dartmouth.

We spent several hours discussing this. The result was a statement of an educational philosophy which we were willing to approve only tentatively, partly because only the man who prepared it for the Committee's consideration was sufficiently satisfied with its phraseology and emphases. We also came to realize that at this stage of our work we did not need to proceed further in defining educational objectives. I seemed to us that the light furnished by our preliminary discussion of principles would enable us to see the merits and defects of the present curriculum, or at least show us the road we should follow toward its improvement. In devising any plan, both ends and means must be con- sidered. The ends, of course, are more important and, ideally, should shape the means. In education, however, as else- where, it must be recognized that not all ideals are attainable. This does not mean for a moment that we intend to proceed as though what is merely practicable or feasible should guide our course. It does mean that we shall have a better understanding of the two sides of the educational process, its principles and its practice, if we pursue our study with both aspects in mind.

For the time being, then, we turned to an examination of the present curriculum and found ready to our hands a problem that was at once of concern to students and faculty, and the study of which would provide an excellent introduction to our larger tasks. The problem is the adaptation of the curriculum to the ROTC programs. The Navy program has been on the campus since the War; last fall the Army and the Air Force ROTC units began to operate. Each program requires one course each semester during a student's four years in college. Almost 75% of last year's freshman class was enrolled in ROTC. Obviously, this is of benefit to the students because deferment from draft requirements permits them to pursue their college EDUcation and at the same time to quality for a commission, and of benefit to the College because it is assured of a substantial student body. Nevertheless, the situation creates difficulties for both students and faculty. How shall the values of a liberal arts education be maintained if a student perforce devotes one fifth of his course time to technical subjects such as ROTC work requires? To be sure, there is educational value in the ROTC courses; nevertheless, the student has 20% less opportunity to study those subjects that are ordinarily regarded as the liberal arts. Dean Morse discussed this problem from the point of view of the entering freshman in "The Cold War and Liberal Education" in the June issue of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE. It is a matter of concern to all ROTC students who will increase in number and to all members of the Faculty.

For these reasons the Committee tackled the problem. We have not solved it. nor do we know of any college that has. We considered many ways o£ alleviating the situation, but almost always came up against the same difficulty: we should have to rob Peter to pay Paul; that is, if we found more free electives, we should have to reduce other work that seemed more valuable. For example and in theory, we could drastically reduce the distributive requirements for freshmen and sophomores, thus leaving students free to concentrate in whatever fields they chose early in their college careers. As a result, many students would fail to obtain a well-balanced foundation in the Humanities, the Social Sciences, and the Sciences. Neither this solution nor that of requiring all ROTC courses to be taken as extras seemed wise. This latter plan would lay a heavy burden on ROTC students, would scatter their energies over too many subjects, and would make the college degree depend on two different sets of requirements. We believe, however, that men who have proved their scholastic ability can carry an extra course with profit, and for this reason one of our recommendations, approved by the Faculty and the Trus- tees, permits an ROTC student with at least a B average in any semester to elect a sixth course the following semester with- out payment of the customary fee.

Another recommendation adopted by the Faculty reduces by two the number of courses required in the major; this not only provides two free electives, but also makes them available in the junior and senior years, when they are most desired. The reduction in the size of the major is regretted by some members of the Faculty, but most of them regard it as the best de- vice for restoring some of the breadth of choice lost by ROTC students. The prob- lem of adjusting the curriculum to ROTC requirements will presumably remain with us for some time, and we shall have to take it constantly into account as we proceed with our effort to establish a proper proportion of prescription and freedom in a student's course program.

A second matter of immediate interest with which the Committee has dealt during the past year has been a study of the Great Issues course. The time for this was appropriate because the course, which had been introduced as an experiment in 1947, was in its fifth year, and a report on the first four years of its life was in preparation by three former Directors, Professors Ballard, Jensen, and A. M. Wilson. President Dickey, to whom the inception of the course was due and who has regularly participated in it, was naturally interested in the report and in our study. He and the three Directors helped actively in the preparation of a questionnaire which was mailed in February to all graduates of the course, some 2,000 men. It was also distributed in May to the men finishing the course in 1952. Moreover, during the last academic year, an undergraduate, Henry Nachman Jr. '5l, with the collaboration of David A. Drexler '52, completed a well conceived and executed survey based on a questionnaire and interviews with ,a representative sample of students taking the course. Our study of all this material and of other information about Great Issues is not yet finished; we hope to complete it this fall, and we plan to have published in the ALUMNI MAGAZINE as soon as possible an article on the subject. We are very grateful to those Great Issues students who answered our questionnaire and especially to the large majority of them who added special comments of their own.

In addition to our attempt to solve the problems of the curriculum related to ROTC and our investigation of the Great Issues course, we have, as was said, considered the best approach into the broad field of the Committee's future work. We decided' to begin with investigation of the freshman and sophomore years. In Dartmouth's curriculum, as in many others, there is a more or less definite break between the first and the last two years. Whether there ought to be is debatable, but it is natural that there should be a shift of emphasis at that point. In his first two years a student is busy learning the nature of college education, developing some basic skills in reading, writing, and a foreign language, and being introduced to various subjects in the three main divisions of knowledge, the Humanities, the Social Sciences, and the Sciences. This work prepares him for the more advanced studies of the junior and senior years, and it enables him to select intelligently the major subject for concentration in the remainder of his college course.

The first two years are thus separable from the others, at least for investigation. They were the subject of special study a few years ago by three committees, each concerned with the work done in one Division. Though certain changes were recom- mended, not many were adopted, and the present Committee on Educational Policy believes that a number of fairly definite questions need to be answered before we can tell whether improvements are needed. Before we can come to sound conclusions we want to have more information than we now possess about entering freshmen; for example: what qualifications of exceptional candidates might warrant their admission to college before they have completed secondary school (Yale, Columbia, Wisconsin, and Chicago are at present experimenting with the admission of such students); what knowledge and abilities do entering freshmen have in significant fields of learning; and what standards is it reasonable to expect students to meet if they wish to gain exemption from various requirements and thus enable themselves to advance more rapidly in college work? (The principle of exemption from required courses on the basis of proficiency examinations was established at Dartmouth five years ago, but the fact that within that time only about thirty students have been excused, except in the foreign languages, seems to suggest that departmental standards may be too high.)

In addition, we feel the need of definite information about the work of the first two years in college: how effectively do the courses in the distributive requirements provide a basis for later specialization, and to what extent does the student gain an understanding of the differences and similarities among the problems and methodologies of the Humanities, the Social Sciences, and the Sciences; what values are gained from foreign language study in college; how effective in various ways is Freshman English; how much instruction is given by lectures and how much in discussion groups; how much writing (papers, quizzes, examinations) is required and should be required of students; and, in general, do students find the work of the first two years intellectually challenging and rewarding? Answers to these and other questions will consume time and effort which we believe will be well spent whether the result is confirmation of present practices or recommendations for change.

Another important field of investigation into which we are beginning to move is the place of preprofessional training in the undergraduate liberal arts college. Dartmouth's graduate schools in medicine, engineering, and business administration exert varying degrees of influence on the curricula of students who wish to be admitted to them. The requirements of some professional organizations, especially in the sciences, necessitate an amount of undergraduate specialization which some persons consider excessive in a liberal arts college. We have known since last fall that we should want to study this subject. We are beginning active consideration of it because the Division of the Sciences late last spring passed a formal vote requesting us to arrange for the study of the premedical curriculum by a committee including representatives of the various groups most concerned. This committee we have established; it is beginning work this fail. A nation-wide study of premedical education, under the auspices of the American Medical Association and the Association of American Medical Colleges and supported by the John and Mary R. Markle Foundation, has been carried on now for almost two years; a two-volume report is probably to be published in January. Our committee will naturally be interested also in the other professional training programs at Dartmouth.

On all matters the members of the Committee are keeping an open mind, not only in refraining from premature judgment but also in being ready to entertain original ideas. Educationally, we are neither conservative nor radical, but liberal. We intend to test searchingly every part of Dartmouth's present curriculum and to admit for ourselves no compromise with what seems imperfect policy or practice.

This account of what the Committee on educational Policy has done and has planned may Well close, as did our report to the Faculty, with an appeal for help. Primary responsibility for Dartmouth's educational policy and practices rests with administrators and teachers in Hanover, but we know that alumni, as well as parents of undergraduates, are much interested. Therefore we hope that all of you will feel free to send us your suggestions and comments. The more widespread the concern with Dartmouth's educational welfare, the more successful the College is likely to be.

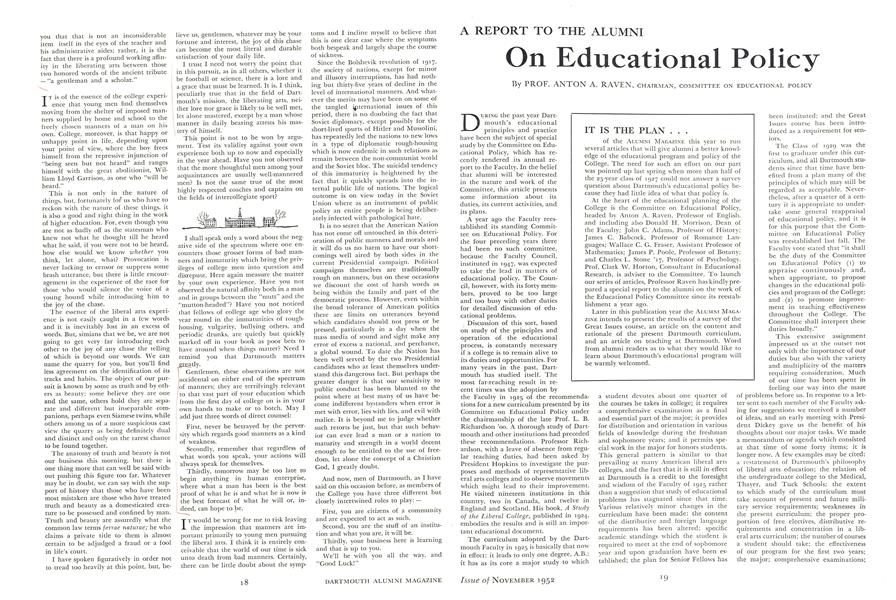

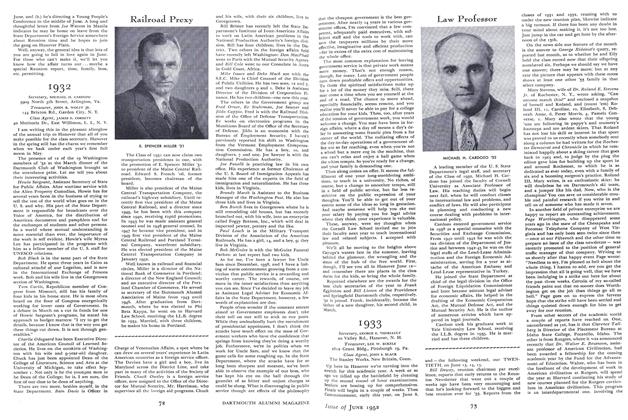

THE COMMITTEE ON EDUCATIONAL POLICY halted its deliberations long enough last month to strike this rather formal pose in the Wren Room of Sanborn English House. L tor: Professors John C. Adams, James C. Babcock, James P. Poole, Anton A. Raven (chairman), Charles L. Stone 17, Clark W. Horton (adviser), Donald H. Morrison and Wallace C. G. Fraser.

THE CENTRAL AIM: "MEN WITH BOTH THE WILL AND THE CAPACITY TO SERVE THE PUBLIC GOOD"

CHAIRMAN, COMMITTEE ON EDUCATIONAL POLICY

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleThe Business of Being a Gentleman

November 1952 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

November 1952 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

November 1952 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, EDWIN C. CHINLUND -

Article

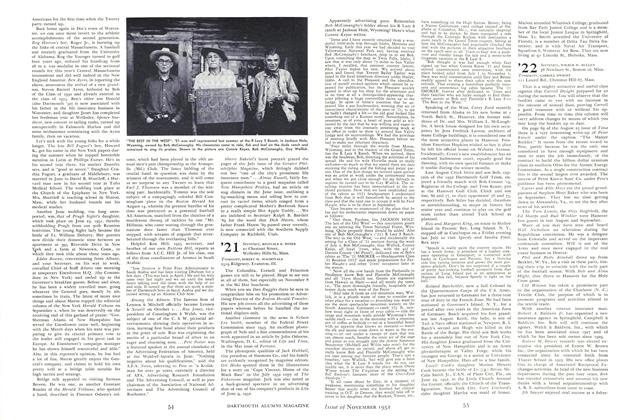

Article"The Greatest Sport"

November 1952 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921

November 1952 By REGINALD B. MINER, ROBERT M. MACDONALD -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

November 1952 By Richard C. Cahn '53