A SCHOOL teacher who is as interested in his students outside the classroom as he is in it, is a rare individual. Paul R. Jenks '94, now retired, was, throughout the span of a full and rewarding career, an extracurricular teacher as well as an out- standing instructor in the classics. Following his retirement from Flushing (N. Y.) High School after 46 years of teaching and making friends with his students, he wrote: "Teaching may be the most fascinating and enjoyable of all professions.... A teacher deals with human nature while it is still plastic and few and far between are those boys and girls who will not smile back at one who understands; and who will not, at least temporarily, show him their best side." Some of these pleasant encounters he describes in the following excerpts from the schoolday reminiscences he has written under the title of The Greatest Sport, which is his definition of teaching.

For years Mr. Jenks has spent his summers in Whitefield, N. H„ close to the Appalachian Mountain Chain. He has passed in- numerable busy winter hours in his workshop in Flushing, making trail signs. He is a nationally known expert in this field and has made more than 5,000 markers for a chain of over 300 miles.

Those who know him best feel that it was not chance that made Mr. Jenks choose as his hobby the making of trail signs —which set hikers on the right path in unknown mountain country, and guide them on their way to the top.

The ALUMNI MAGAZINE regrets that it has space for only a few of Mr. Jenks' reminiscences. They serve, however, to indicate something of the good he accomplished and the satisfactions he enjoyed.

A KNOCKDOWN

I was sitting alone in charge of the boys' lunch room, probably thinking about White Mountain trails; the line of boys at the counter was nearly served, everything was normal, and why should I look for trouble? Daniel did not prod the lions.

All of a sudden, at the end of the line, just within my range of vision, I saw an arm shoot out straight from a shoulder and the boy in front drop in his tracks to the floor. Silence came over the room. Two boys helped the victim to his feet. The rest looked at me.

Of course my impulse was to rush to the scene but something held me back until I had done some thinking. I had seen the blow and I knew the author, a clean-cut, hot tempered Southern boy. There had been no comeback from the victim or his friends. It was no time to do anything that would add to the tension in the room.

I rose and leisurely strolled over to the aggressor, who was expecting me and then some. "B , did he deserve that?" I asked him quietly. "Yes, Mr. J., he did." "You're sure of it?" "Yes, sir." "All right; I may look into it a little. That's all, B." And I went back to my chair. The tension in the room was gone.

THE SPARROW

One day long years ago a boy had made a peculiarly vile mess of an easy passage in Caesar; but instead of the usual sarcasm that I would have poured out upon him, it occurred to me merely to remark that I was not all surprised at his performance, because I knew what he had been doing the evening before when he was supposed to be studying his Latin.

At the end of the period he came to the desk and asked, "How did you know what I was doing last night?" "Oh," I said, "a little bird told me." "What little bird?" "Well, Smith, I have a trained sparrow, that flies around Flushing for me during the evening, looks in at the windows, and reports to me what boys and girls are doing."

Thus was born the myth of my sparrow, so utterly absurd that. for that very reason it took hold. It was much better all around for me to use the assistance of this fabulous bird than to employ the stock processes of the classroom. If a boy clearly had not studied his lesson, it was far pleasanter and more effective to quote the alleged report of the sparrow than to jump on him personally, because the class would enjoy his discomfiture at the hands (or claws) of a silly bird; if it drew a laugh from the class, so much the better!

Gradually the myth spread; and when one day a not-too-brainy but good-natured class presented me with a papier-mache sparrow, the idea was irrevocable. The bird sat on my desk at every Christmas time, was sometimes presented with some poisoned (?) bird seed, and seemed to confirm the physical existence in life of my hated petl

So utterly ridiculous was the idea that it appealed to some of the brainiest pupils to extend the myth. When I took over the school for a term, the incoming Freshmen were solemnly warned by the editor of the school paper (now a Ph.D., with all sorts of honors) that they would better behave and study, because I was assisted by a mysterious bird, who would report to me all their sins and wickednesses!

The champion chess player wrote a serious article about the bird, and there was scarcely an issue of the school magazine without some reference to it; or a poem, like one by an honor student, beginning, "Birdie of the evil eye;" etc.

A later addition to the myth was to the efEect that the bird had a tarnhelm and sat on my desk and told me whom to call for recitation, always naming one who "knew everything in the lesson" except the point in question. Sometimes I asked the bird whom I should call, or made a bet with the class that he would name three pupils in succession who would fail. It was great fun, especially with wriggly first-termers in the later periods of the day!

Now when I happen to meet one of the old- timers, like the young man who sells me our groceries, he is quite as likely to inquire for the health of the sparrow as for mine.

PAYING A DEBT

He was an Italian boy, pleasant, popular with both students and faculty, a good scholar, accepted by the leading university in the city. Just before the Christmas holidays of his first year there, he blew into my office. "Mr. J.," he said, "you once told us that a city boy should go to a college in the country. Will you tell me why you think so?"

For ten minutes I gave him my reasons, while he searched my face. When I finished, he said, "Now I see why college hasn't been to me what I expected. Do you suppose Dartmouth would take me next year?"

A year from the following May, when he was out over the weekend on the trails of the Dartmouth Outing Club, he was stricken with acute appendicitis and reached the hospital just in time. As he lay convalescing, he wrote to one of "my" girls: "I'm getting along all right, but it's a nightmare to figure out how I'm going to catch up in my subjects and pay my bills." Which the girl dutifully and promptly reported to me.

An hour later a note was in the teachers' letter boxes. "Did you know —? I£ not, throw this into the waste basket; if you did, here is something you'll want to know...

Within three days, accepting minimum offers only, I had in hand, subscribed by the faculty and the principal's Lions Club, funds more than sufficient to pay all the charges at the infirmary. With some natural hesitation he accepted my remittance.

When Joe came back to our school late in June, I could see that he was ill at ease with me, as never before. "Joe, come down to my r00m.... Joe, you feel that you're in debt to me for something that you received last month. Now I want to tell you a story.

"Does the name 'Towle' mean anything to you?" "Yes; you helped him to write our textbook in Caesar, didn't you?" "Do you know anything about him?" "No." "Well, let me tell you. He was a Dartmouth man, '76. He helped me to secure my first position in this city. He made it possible for me to marry. He took me on as his assistant in writing that textbook. He backed me for promotion and did us lots of personal kindnesses. I never repaid him because I couldn't. But don't you think he'd feel that I was a pretty poor sort of Dartmouth man if I didn't do something to help another, as he helped me?"

The smile came back to Joe's face. "I get you!" "Well, Joe, if in ten years you find a chance to help another Dartmouth man, just think how pleased Harry Towle will be."

Two years later Joe graduated with prizes and honors and Phi Beta Kappa rank.

"HAEC STUDIA NON IMPEDIUNTFORIS"

[These studies are no hindrance in the great open spaces] (A letter from one of our boys in the Service)

"Our outfit had been all day on a practice march and we were returning in the late afternoon tired and footsore. As we were coming down a ravine, we heard a big tree fall.

"At once I was back in Room 4, recalling how Virgil had written, 'as a great pine falls on Erymanthus'; and how you had told the class of hearing a dead tree fall in the evening when you and your friends were sitting around your campfire in the mountains.

"And for the rest of the distance back to camp my weariness was forgotten and I thought only about those hours in the Virgil class."

FORTY YEARS AFTER!

[Part o£ a letter from the Registrar of University]

"I entered Boys' High School in 1903, but because of my father's death and my family's moving away from Brooklyn I was obliged to leave school about three months later. I reported to the office and you told me you were very sorry that I had to leave; but you were confident that I would be successful where- ever I might go; you shook my hand and said 'Goodbye.'

"Now I want to tell you that your kindly gesture and goodness to a young boy who didn t know where he was heading have never been forgotten. One of my duties for thirty years has been to have constant conferences with boys and their parents; and it has always been my effort to handle these young men with the same kindness and consideration that you showed to me.

"Perhaps-you may think that what you did was just ordinary, but you should have the pleasure of knowing that that one small gesture has stayed with one of your boys through his life; and I hope that I, too, may at some time have acted in a manner which has left a similar impression."

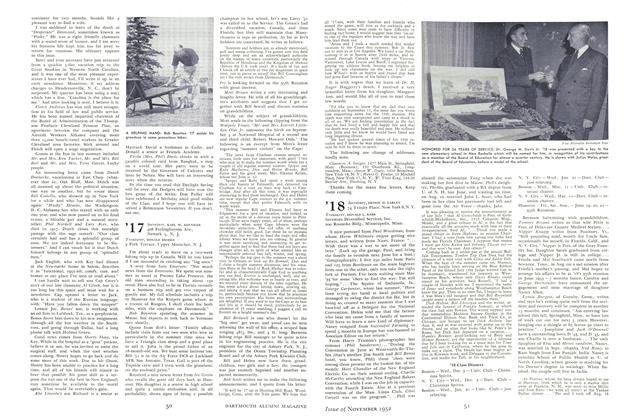

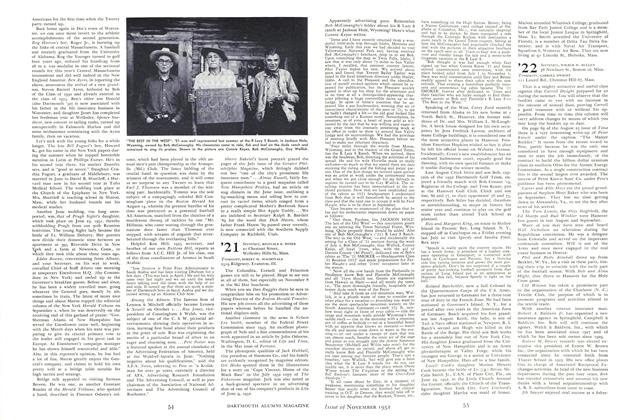

PAUL R. JENKS '94, who calls teaching "The Greatest Sport," is the author of the sketches on this page, recalling some of his memorable experiences during 46 years of teaching and administrative work in high schools.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleOn Educational Policy

November 1952 By PROF. ANTON A. RAVEN -

Article

ArticleThe Business of Being a Gentleman

November 1952 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

November 1952 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

November 1952 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, EDWIN C. CHINLUND -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921

November 1952 By REGINALD B. MINER, ROBERT M. MACDONALD -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

November 1952 By Richard C. Cahn '53

Article

-

Article

ArticleCOLLEGE SCHOLARSHIP

March 1916 -

Article

ArticleJANSSEN EX-'21, COMPOSER, RECEIVES HONORARY DEGREE

December, 1923 -

Article

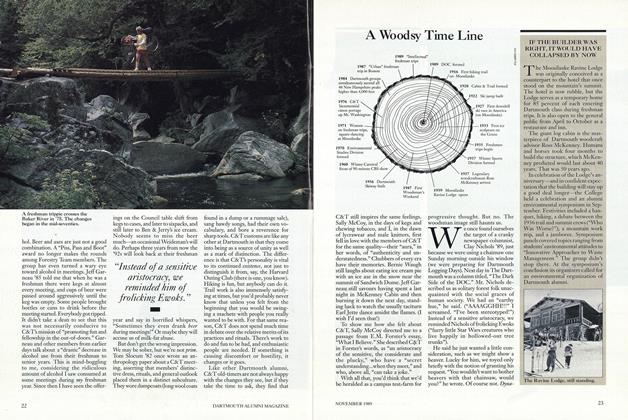

ArticleIF THE BUILDER WAS RIGHT, IT WOULD HAVE COLLAPSED BY NOW

NOVEMBER 1989 -

Article

ArticleWinter Schedules

December 1954 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Article

ArticleSenior With a Sideline

May 1952 By R. L. A. -

Article

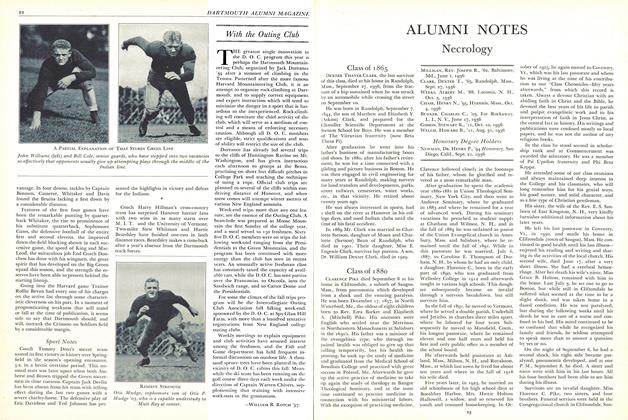

ArticleWith the Outing Club

November 1936 By William B. Rotch ’37