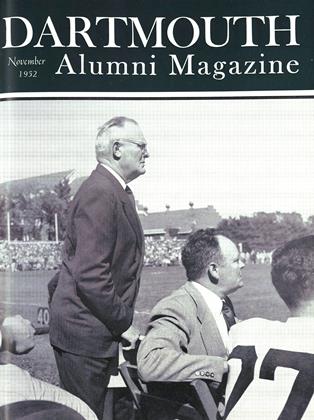

GENTLEMEN OF THE COLLEGE: I want to talk with you this morning about your use of the privilege which this convocation symbolizes the opening of another college year in America. For Dartmouth it is the 184th such year, although for the United States of America it is only the 177th. For you old- timers of the senior class it is the last in a cycle of four and for you young fellows in the balcony it is the first of what we all greatly hope may be four.

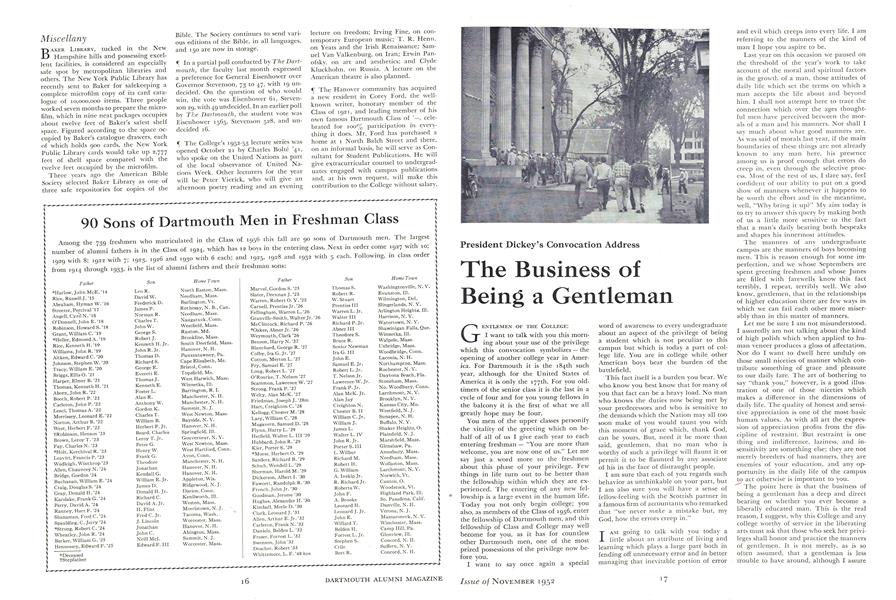

You men of the upper classes personify the vitality of the greeting which on be- half of all of us I give each year to each entering freshman "You are more than welcome, you are now one of us." Let me say just a word more to the freshmen about this phase of your privilege. Few things in life turn out to be better than the fellowship within which they are experienced. The entering of any new fellowship is a large event in the human life. Today you not only begin college; you also, as members of the Class of 1956, enter the fellowship of Dartmouth men, and this fellowship of Class and College may well become for you, as it has for countless other Dartmouth men, one of the most prized possessions of the privilege now before you.

I want to say once again a special word of awareness to every undergraduate about an aspect of the privilege of being a student which is not peculiar to this campus but which is today a part of college life. You are in college while other American boys bear the burden of the battlefield.

This fact itself is a burden you bear. We who know you best know that for many of you that fact can be a heavy load. No man who knows the duties now being met by your predecessors and who is sensitive to the demands which the Nation may all too soon make of you would taunt you with this moment of grace which, thank God, can be yours. But, need it be more than said, gentlemen, that no man who is worthy of such a privilege will flaunt it or permit it to be flaunted by any associate of his in the face of distraught people.

I am sure that each of you regards such behavior as unthinkable on your part, but I am also sure you will have a sense of fellow-feeling with the Scottish partner in a famous firm of accountants who remarked that "we never make a mistake but, my God, how the errors creep in."

I AM going to talk with you today a little about an attribute of living and learning which plays a large part both in fending off unnecessary error and in better managing that inevitable portion of error and evil which creeps into every life. I am referring to the manners of the kind of man I hope you aspire to be.

Last year on this occasion we paused on the threshold of the year's work to take account of the moral and spiritual factors in the growth of a man, those attitudes of daily life which set the terms on which a man accepts the life about and beyond him. I shall not attempt here to trace the connection which over the ages thoughtful men have perceived between the morals of a man and his manners. Nor shall I say much about what good manners are. As was said of morals last year, if the main boundaries of these things are not already known to any man here, his presence among us is proof enough that errors do creep in, even through the selective process. Most of the rest of us, I dare say, feel confident of our ability to put on a good show of manners whenever it happens to be worth the effort and in the meantime, well, "Why bring it up?" My aim today is to try to answer this query by making both of us a little more sensitive to the fact that a man's daily bearing both bespeaks and shapes his innermost attitudes.

The manners of any undergraduate campus are the manners of boys becoming men. This is reason enough for some imperfection, and we whose Septembers are spent greeting freshmen and whose Junes are filled with farewells know this fact terribly, I repeat, terribly well. We also know, gentlemen, that in the relationships of higher education there are few ways in which we can fail each other more miserably than in this matter of manners.

Let me be sure I am not misunderstood. I assuredly am not talking about the kind of high polish which when applied to human veneer produces a gloss of affectation. Nor do I want to dwell here unduly on those small niceties of manner which contribute something of grace and pleasure to our daily fare. The art of bothering to say "thank you," however, is a good illustration of one of those niceties which makes a difference in the dimensions of daily life. The quality of honest and sensitive appreciation is one of the most basic human values. As with all art the expression of appreciation profits from the discipline of restraint. But restraint is one thing and indifference, laziness, and insensitivity are something else; they are not merely breeders of bad manners, they are enemies of your education, and any opportunity in the daily life of the campus to act otherwise is important to you.

The point here is that the business of being a gentleman has a deep and direct bearing on whether you ever become a liberally educated man. This is the real reason, I suggest, why this College and any college worthy of service in the liberating arts must ask that those who seek her privileges shall honor and practice the manners of gentlemen. It is not merely, as is so often assumed, that a gentleman is less trouble to have around, although I assure you that that is not an inconsiderable item itself in the eyes o£ the teacher and his administrative aides; rather, it is the fact that there is a profound working affinity in the liberating arts between those two honored words of the ancient tribute "a gentleman and a scholar."

IT is of the essence of the college experience that young men find themselves moving from the shelter of imposed manners supplied by home and school to the freely chosen manners of a man on his own. College, moreover, is that happy or unhappy point in life, depending upon your point of view, where the boy frees himself from the repressive injunction of "being seen but not heard" and ranges himself with the great abolitionist, William Lloyd Garrison, as one who "will be heard."

This is not only in the nature of things, but, fortunately for us who have to reckon with the nature of these things, it is also a good and right thing in the work of higher education. For, even though you are not as badly off as the statesman who knew not what he thought till he heard what he said, if you were not to be heard, how else would we know whether you think, let alone, what? Provocation is never lacking to censor or suppress some brash utterance, but there is little encouragement in the experience of the race for those who would silence the voice of a young hound while introducing him to the joy of the chase.

The essence of the liberal arts experience is not easily caught in a few words and it is inevitably lost in an excess of words. But, simians that we be, we are not going to get very far introducing each other to the joy of any chase the telling of which is beyond our words. We can name the quarry for you, but you'll find less agreement on the identification of its tracks and habits. The object of our pursuit is known by some as truth and by others as beauty; some believe they are one and the same, others hold they are separate and different but inseparable companions, perhaps even Siamese twins, while others among us of a more suspicious cast view the quarry as being definitely dual and distinct and only on the rarest chance to be found together.

The anatomy of truth and beauty is not our business this morning, but there is one thing more that can well be said with- out pushing this figure too far. Whatever may be in doubt, we can say with the support of history that those who have been most mistaken are those who have treated truth and beauty as a domesticated creature to be possessed and confined by man. Truth and beauty are assuredly what the common law terms jerrae naturae; he who claims a private title to them is almost certain to be adjudged a fraud or a fool in life's court.

I have spoken figuratively in order not to tread too heavily at this point, but, be- lieve us, gentlemen, whatever may be your fortune and interest, the joy of this chase can become the most literal and durable satisfaction of your daily life.

I trust I need not worry the point that in this pursuit, as in all others, whether it be football or science, there is a lore and a grace that must be learned. It is, I think, peculiarly true that in the field of Dartmouth's mission, the liberating arts, neither lore nor grace is likely to be well met, let alone mastered, except by a man whose manner in daily bearing attests his mastery of himself.

This point is not to be won by argument. Test its validity against your own experience both up to now and especially in the year ahead. Have you not observed that the more thoughtful men among your acquaintances are usually well-mannered men? Is not the same true of the most highly respected coaches and captains on the fields of intercollegiate sport?

I shall speak only a word about the negative side o£ the spectrum where one encounters those grosser forms of bad manners and immaturity which bring the privileges of college men into question and disrepute. Here again measure the matter by your own experience. Have you not observed the natural affinity both in a man and in groups between the "mutt" and the "mutton-headed"? Have you not noticed that fellows of college age who glory the year round in the immaturities of rough- housing, vulgarity, bullying others, and periodic drunks, are quietly but quickly marked off in your book as poor bets to have around when things matter? Need I remind you that Dartmouth matters ECgatly.

Gentlemen, these observations are not accidental on either end of the spectrum of manners; they are terrifyingly relevant to that vast part of your education which from the first day of college on is in your own hands to make or to botch. May I add just three words of direct counsel:

First, never be betrayed by the perversity which regards good manners as a kind of weakness.

Secondly, remember that regardless of what words you speak, your actions will always speak for themselves.

Thirdly, tomorrow may be too late to begin anything in human enterprise, where what a man has been is the best proof of what he is and what he is now is the best forecast of what he will or, indeed, can hope to be.

It would be wrong for me to risk leaving the impression that manners are im- portant primarily to young men pursuing the liberal arts. I think it is entirely conceivable that the world of our time is sick unto death from bad manners. Certainly, there can be little doubt about the symptoms and I incline myself to believe that this is one clear case where the symptoms both bespeak and largely shape the course of sickness.

Since the Bolshevik revolution of 1917, the society of nations, except for minor and illusory interruptions, has had nothing but thirty-five years of decline in the level of international manners. And what- ever the merits may have been on some of the tangled international issues of this period, there is no doubting the fact that Soviet diplomacy, except possibly for the short-lived spurts of Hitler and Mussolini, has repeatedly led the nations to new lows in a type of diplomatic rough-housing which is now endemic in such relations as remain between the non-communist world and the Soviet bloc. The suicidal tendency of this immaturity is heightened by the fact that it quickly spreads into the internal public life of nations. The logical outcome is on view today in the Soviet Union where as an instrument of public policy an entire people is being deliberately infected with pathological hate.

It is no secret that the American Nation has not come off untouched in this deterioration of public manners and morals and it will do us no harm to have our short- comings well aired by both sides in the current Presidential campaign. Political campaigns themselves are traditionally rough on manners, but on these occasions we discount the cost of harsh words as being within the family and part of the democratic process. However, even within the broad tolerance of American politics there are limits on utterances beyond which candidates should not press or be pressed, particularly in a day when the mass media of sound and sight make any error of excess a national, and perchance, a global wound. To date the Nation has been well served by the two Presidential candidates who at least themselves understand this dangerous fact. But perhaps the greater danger is that our sensitivity to public conduct has been blunted to the point where at best many of us have become indifferent bystanders when error is met with error, lies with lies, and evil with malice. It is beyond me to judge whether such retorts be just, but that such behavior can ever lead a man or a nation to maturity and strength in a world decent enough to be entitled to the use of freedom, let alone the concept of a Christian God, I greatly doubt.

And now, men of Dartmouth, as I have said on this occasion before, as members of the College you have three different but closely intertwined roles to play:

First, you are citizens of a community and are expected to act as such.

Second, you are the stuff of an institution and what you are, it will be.

Thirdly, your business here is learning and that is up to you.

We'll be with you all the way, and "Good Luck!"

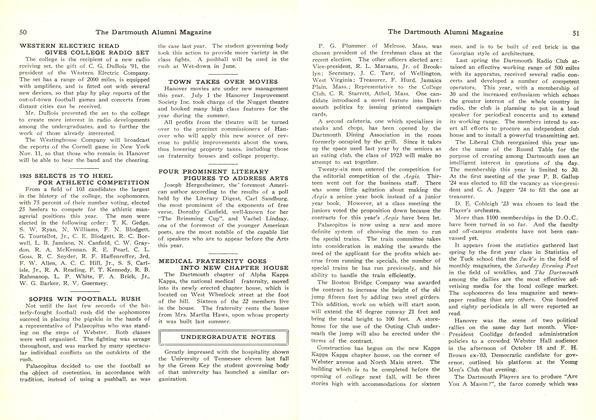

President Dickey's Convocation Address

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleOn Educational Policy

November 1952 By PROF. ANTON A. RAVEN -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

November 1952 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

November 1952 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, EDWIN C. CHINLUND -

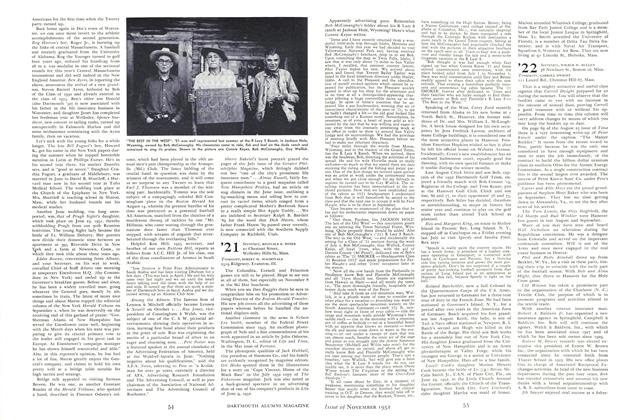

Article

Article"The Greatest Sport"

November 1952 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921

November 1952 By REGINALD B. MINER, ROBERT M. MACDONALD -

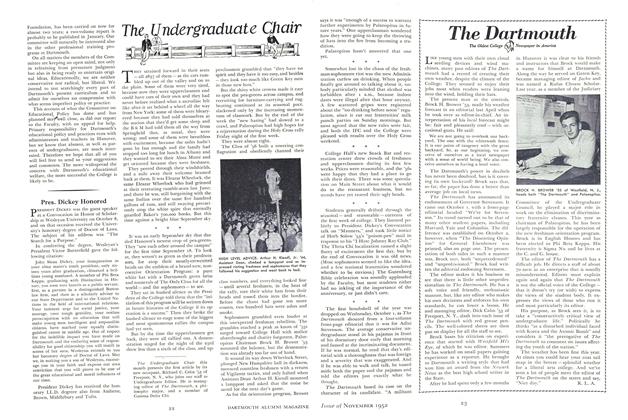

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

November 1952 By Richard C. Cahn '53