Following is the full text of the address delivered by Dr. Fuess in Webster Hall, October 17, at the Dartmouth Night convocation honoring Daniel Webster on the 100th anniversary of his death. Dr. Fuess, former headmaster of Phillips Academy at Andover and author of the definitive life of Webster, received Dartmouth's honorary Doctorate of Letters in 1931.

ONE hundred years ago at seven o'clock on a bright Sunday morning in October, the citizens of Marshfield, Massachusetts, heard the great bell of the parish church ringing violently, -the traditional signal that a death had occurred in the community. Then followed three times three strokes, indicating that it was a male person who had died. Finally the bell tolled solemnly seventy times, to denote the age of the deceased. Every man and woman within its sound knew what that meant. Their great friend and neighbor, Daniel Webster, who had been ailing, was dead. Emerson recorded in his Journal, "The sea, the rocks, the woods, gave no sign that America and the world had lost the completest man."

Five days later, on October 29, the coffin was placed on the lawn in front of the Webster house, open entirely to the sun. In it lay Webster as he had been in life, wearing his blue coat with brass buttons, a white vest and cravat, pantaloons, gloves, shoes, and dark cloth gaiters. On what was described as a "heavenly day," the sun shimmered down through the trees directly on his face. Thousands of visitors walked to the bier two by two and then separated, one going on each side. Franklin Pierce was there, about to be elected President of the United States. So were local fishermen and laborers on the Marshfield farm. Among that vast crowd also were four Dartmouth undergraduates who had come all the way from Hanover as representatives of the college. This was very fitting, for although they may have been unnoticed, their presence was symbolic of a relationship which has never been broken.

Although Dartmouth has had many famous sons, I suppose that few will question the claim that Daniel Webster is the foremost. He entered in the autumn of 1797, when he was not yet sixteen, but it was not long before he was recognized as the ablest man on the campus. He himself was not reluctant to admit this; and when years afterward Professor Sanborn said to him, "It is commonly reported that you did not study much in college," Webster burst out, "I studied and read more than all the rest of my class, if they had all been made into one man. And I was as much above them all then as I am today." If Dartmouth students are characterized nowadays by humility, Daniel Webster did not set the fashion.

There was no football for "Black Dan" to play, although he would have made in my opinion a first-rate defensive tackle. There was no ski team or outing club on which he could win distinction. But he did have a voice, and the only competition open to him was oratory, a field in which he could and did excel. In 1800, when he was only nineteen, the citizens of the village of Hanover invited him to deliver the Independence Day oration, which was spoken in the meeting house. It was natural that he should glorify his country and his college. Indeed he declaimed at one point:

"Yale, Providence, and Harvard now grace our land; and Dartmouth, towering majestic above the groves which encircle her, now inscribes her glory on the registers of fame! Oxford and Cambridge, those oriental stars of literature, shall now be lost, while the bright sun of American science displays his broad circumference in uneclipsed radiance."

Perhaps it was typical of his generation in America that he could dismiss Oxford and Cambridge so casually!

Of all the orators heard at the recent Chicago conventions, probably General MacArthur most resembled Webster in his sesquipedalian grandeur and dignified grandiloquence, but even his rolling periods lacked something of their original. In his undergraduate days Webster was too expansive for our modern taste. In a funeral oration on his classmate, Ephraim Simonds, spoken in June, 1801, Dan'l outdid even himself, saying:

"Simonds shall never be forgotten. The future child of Dartmouth, as he treads o'er the mansions of the dead, with his hand on his bosom shall point, 'There lies Simonds!' and however careless of his eternal being, however immersed in dissipation or frozen apathy, he shall check for a moment the tide of mirth, and while an involuntary tear starts in his eye, shall read: Hie jacet, quem religioat scientia condecoraverunt."

As an Amherst man, I find it difficult to believe that any Dartmouth graduate could be either "immersed in dissipation" or "frozen in apathy"; and it is equally hard to imagine the average sophomore pointing with his hand on his bosom and translating at sight the Latin on an ancient tombstone.

THE bathos into which Webster lapsed at Dartmouth was transformed into nobility as he gained in stature, and he was to employ eloquence with lasting effect in March, 1818, when he argued the Dartmouth College Case before the Supreme Court of the United States. Whatever obligation he owed to his alma mater was there paid back with interest as he established for future Trustees the inviolability of the charter of incorporation of an institution of learning, and incidentally of the stability of contracts in general. I am aware that all Dartmouth men are supposed to weep when they hear the classic peroration about the small college and those who love it, and I have no intention of making this audience lachrymose. Rather I prefer to mention the dinner which Webster, solus at unus, gave to Dartmouth alumni in September, 1850, when he was Secretary of State. After dinner, a discussion arose as to which of his arguments had been the most remarkable; and when various judgments had been expressed, Webster rose, pushed back his chair, passed his hand across his forehead in his favorite gesture, and then talked for an hour reviewing his accomplishments. It was, he declared, his college which gave him his first important opportunity. "I am poor," he concluded, "I have done for Dartmouth all that I can. Yet I feel indebted to her, indebted for my early education, indebted for her early confidence, indebted for a chance to show to men, whose support I was to Meed for myself and my family, that I was equal to the defense of vested interests against state courts and sovereignties."

Thinking again of Dartmouth, I cannot ignore the Discourse Commemorative ofDaniel Webster spoken on July 27, 1853, in the colonial church bordering the green, by Rufus Choate of the Class of 1819. One great Dartmouth man was speaking to a Dartmouth audience about Dartmouth's greatest alumnus. One of the nation's finest orators was eulogizing another. Choate spoke for three hours in an oration of approximately 26,000 words, including what is probably the longest sentence ever uttered by human lips, covering 1200 words and taking more than ten minutes to finish. One of those who heard it doubted whether Choate could ever make port without a "wreck of grammar and connection," but he emerged triumphant, to the amazement of his apprehensive listeners.

I LAST spoke on Daniel Webster in this hall in 1932, on the 150th anniversary of his birth. It was in the midst of a vigorous political campaign between Herbert Hoover and Franklin D. Roosevelt. Now, twenty years later, Republicans and Democrats are again coming nobly to the grapple. Webster would have enjoyed these contests, for he was himself almost a perennial candidate for the Presidency. Furthermore the implications of the Nixon incident would have been old stuff to him. In 1846, when at their solicitation Webster agreed to return to the Senate after having been for some months in private life, a group of the Solid Men of Boston subscribed the sum of 137,000 and arranged to have the income from this amount paid to him semi-annually. Webster had no hesitation whatever in accepting this sum as compensation for the professional fees which he had renounced. During the summer of 1850, when he was offered a post in Fillmore's cabinet, he held up his decision until he was sure that he would be "cared for," and to that end forty New York business men contributed §500 apiece, agreeing to pay the amount in ten quarterly installments. At an earlier period, while he was in the Senate and debating the matter of the rechartering of the Bank of the United States, he continued to accept retainers from the Bank and actually on one occasion wrote a pointed note complaining that his retaining fee had not been "sweetened" for several months. Although he had been born in a house as simple as a log cabin, he claimed like a monarch the homage and the tribute of his constituents. Whenever he was pressed on the subject, he declared that it was worth the money to have a man of his quality in public office!

In 1900, when ballots were cast by ninety-seven electors for candidates for the Hall of Fame, George Washington led, with 97 votes. Webster and Lincoln each had 96, and they were followed by Franklin with 94 and Jefferson with only 91. Probably as a statesman he does not stand so high today with contemporary historians, and Jefferson no doubt would be rated higher. Why is this? It seems to me that Daniel Webster fitted perfectly the need of his times, the period between the Revolution and what my Southern wife has taught me to call the War Between the States. It was essential that the Federal Union, established in 1789 by such a narrow margin and existing in those early days so precariously, should be made powerful. His task as a political philosopher and leader was to keep the Union from breaking up into smaller parts and to steady the Ship of State when sectionalists like Calhoun insisted 011 rocking it. As a temperamental conservative, he was suited to perform the function of defender and preserver. In several critical cases and debates he became the advocate of the Union; indeed he postponed the Civil War by a full decade, thus allowing the North to gain strength and superiority. This was his special contribution to our development as a nation, and it was a very great contribution!

But after 1933, with the accession of Franklin D. Roosevelt to the Presidency, the temper of the majority of the American people was different. Webster did not believe in governmental experiment or change. Furthermore, although he was kind to the laborers on his estates, he was not much interested in humanitarian movements, —in the improvement of working conditions in factories, in the mitigation and elimination of disease, in the whole business of social security. Not liking reformers and radicals, he took his stand on the side of the established order, the protection of property rights, and the maintenance of a stable society. He had no love for Thomas Jefferson and he certainly would not have approved of the philosophy of the New Deal.

In 1933, after a temporary resurrection under President Woodrow Wilson, Thomas Jefferson came into his own. This is no place to analyze the relationship of the so-called New Deal to Jefferson and Andrew Jackson. The significant point is that for twenty years conservatism as a political principle has not found favor with the voters. Indeed the hour came when Samuel G. Blythe could describe the Republican Party as "a dead whale stranded on the beach." Further, by a final strange irony, the conception of a strong central government was appropriated by the Democratic Party, which Webster had opposed as the party of State Rights. All in all, Webster is happier where he is, at rest in his tomb at Marshfield. He would not have enjoyed the political trend of the last twenty years.

NEVERTHELESS Dartmouth men need make no apologies for Daniel Webster. This country might well have foundered had it not been for him and his ringing words. Furthermore his personality was as striking as his accomplishment. In all our 160 million people today we have no one comparable with him. Stephen Vincent Benet described him as "a man with a mouth like a mastiff, a brow like a mountain, and eyes like burning anthracite." Those who wrote of him compared him with natural phenomena, like Mount Washington and Niagara Falls and the Mississippi River. A magnificent human animal with one of the largest brains ever recorded, he stood and walked and talked like a King of Men, like Agamemnon or Charlemagne. In 1842, when he confronted in Faneuil Hall a body of hostile Whigs who had planned to ostracize him, he stood before them in all his majesty and fixed them with his blazing black eyes. With supreme arrogance, he cried, "Gentlemen, I am a Whig, a Massachusetts Whig, a Faneuil Hall Whig, and if you break up the Whig Party, where am I to go?" Under such circumstances many men would have been told quickly where they could go. But not Dan'l Webster! As his audience heard again the well-remembered voice, they broke into applause, loud and unrestrained. The reconciliation was complete, but on his terms!

Webster delivered his speeches without amplifiers, and it was said that at Bunker Hill, fortified by a tumbler of brandy, he could be heard and understood half a mile away. The radio would probably disturb him, for he usually spoke for two hours, and sometimes more. But over television, with his personality, he would be a "natural," a match for any opponent. The only figure in our time who is his equal is Winston Churchill, with his oratorical style like rich brocade and his picturesque individuality.

Since I last spoke here "Steve" Benet has published his brilliant short story, The Devil and Daniel Webster, which opens as follows:

"Yes, Dan'l Webster's dead, —or at least they buried him. But every time there's a thunderstorm around Marshfield. they say you can hear his rolling voice on the hollows of the sky. And they say that if you go to his grave and speak loud and clear, 'Dan'l Webster, Dan'l Webster!', the ground'll begin to shiver and the trees to shake. And after a while you'll hear a deep voice saying, 'Neighbor, how stands the Union?' Then you'd better answer the Union stands as she stood, rock-bottomed and copper-sheathed, one and indivisible, or he's liable to rear right up out of the ground. At least that's what I was told when I was a youngster."

Just about one hundred years ago thisday, Daniel Webster, a dying man in his home at Marshfield, presented to his physician, Dr. John Jeffries, the gold watch which he had carried for many years. With characteristic thoughtfulness he even had an inscription engraved on it to mark the occasion. This was handed down by Dr. Jeffries to his descendants, and was finally given to me in 1945 by one of them, Mrs. Howard Means. On special occasions I always carry it. It still keeps perfect timeIndeed I checked the hour from it as I entered Webster Hall this evening. And' it delights me that here, holding in my hand the watch which he wore when he delivered the Seventh of March Speech and speaking in the hall which bears his- name on the campus of the college which he loved, I have some tangible link with the great American who stood so coura- geously for "Liberty and Union, Now and Forever, One and Inseparable." Daniel Webster's spirit, patriotic, comprehensive and magnetic, must walk abroad on Dart- mouth Night, proud of the college which he did so much to preserve and adorn.

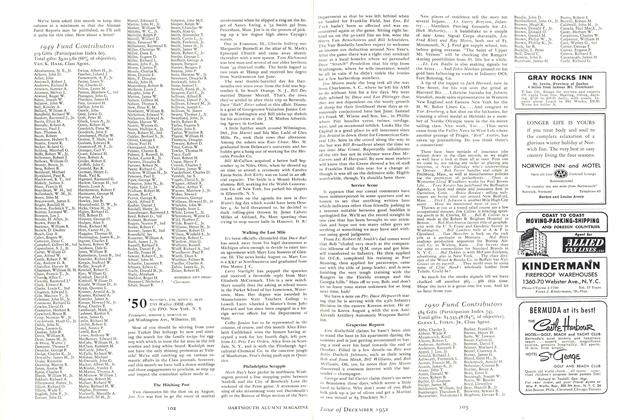

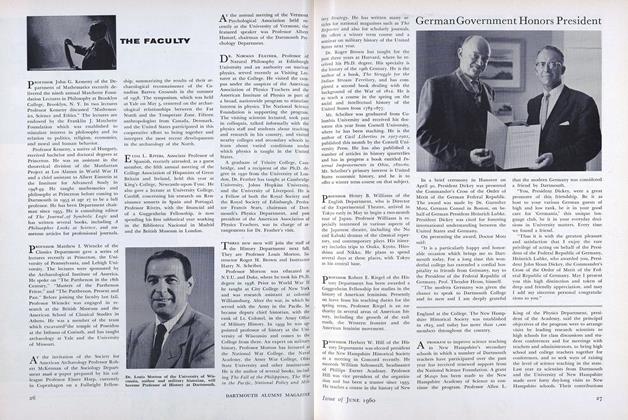

DANIEL WEBSTER'S SHAY: Removed from its humble place of safe-keeping in a college shed, Dan'l's own shay was shined up, and taken piece by piece into the lobby of Baker. There, re- assembled, it is being admired by Dr. Claude M. Fuess '31h (center), Webster's biographer; Edward C. Lathem '51 (1), and Richard W. Morin '24, Librarian.

CENTENNIAL TRIBUTE: As a gift to the town of Marshfield, Mass., Dartmouth's Trustees presented a bronze tablet on October 24, the centennial of Webster's death. Speakers at the ceremony in Winslow Cemetery in Marshfield, included (I to r): President Dickey; Samuel P. Sears, president of the Massachusetts Bar Association; Leverett Saltonstall, Senator from Massa- chusetts; and David Twomey, State Commander of the Veterans of Foreign Wars.

"TRADITION IS REMEMBERING": Dartmouth alumni from the Marshfield area who attended the ceremonies there marking the 100 th anniversary of Daniel Webster's death included (I to r): William C. King '27, Oliver L. Barker '26, Maurice A. Hall '19, Tracy W. Hatch '22, John R. Hubbard '29, Hargreaves Heap Jr. '27, Edward C. Ford '09, co-chairman of the Marshfield committee in charge of the memorial program, and Dr. Wallace H. Drake '14.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

December 1952 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1950

December 1952 By ENS. SCOTT C. OLIN, SIMOND J. MORAND III -

Class Notes

Class Notes1935

December 1952 By HENRY R. BANKART, JOHN WALLACE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1915

December 1952 By PHILIP K. MURDOCK, RUSSELL J. RICE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1928

December 1952 By OSMUN SKINNER, JOHN PHILLIPS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

December 1952 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, EDWIN C. CHINLUND

Article

-

Article

ArticlePHI BETA KAPPA CELEBRATION

March, 1914 -

Article

ArticleGIVES CUP FOR LEDYARD CANOE CLUB VOYAGEURS

February 1921 -

Article

ArticleBOSTON SYMPHONY, MARTIN AND ELMAN TO GIVE CONCERTS

November, 1922 -

Article

ArticleGerman Government Honors President

June 1960 -

Article

ArticleA Wah Hoo Wah for —

FEBRUARY 1968 -

Article

ArticleValedictory to 1959

JULY 1959 By PRESIDENT JOHN SLOAN DICKEY