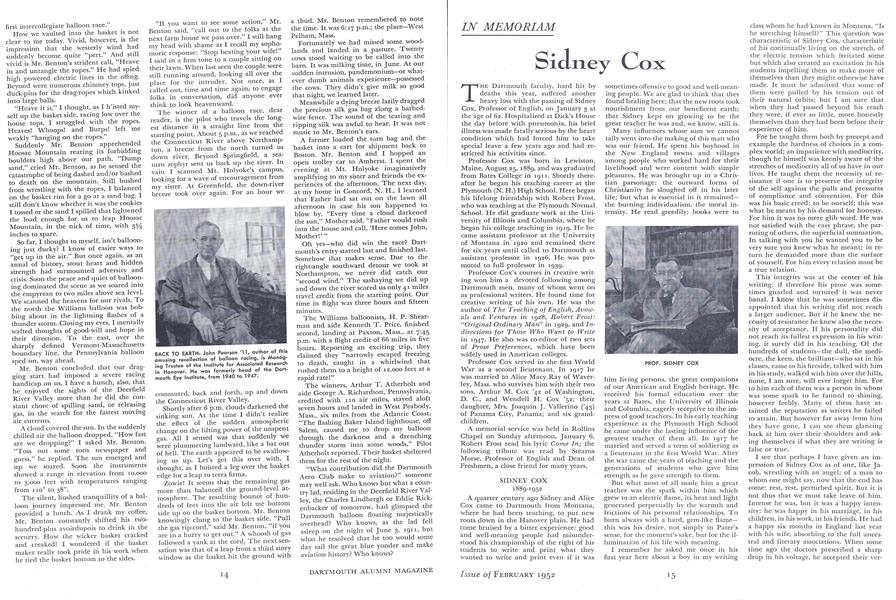

THE Dartmouth faculty, hard hit by deaths this year, suffered another heavy loss with the passing of Sidney Cox, Professor of English, on January 3 at the age of 62. Hospitalized at Dick's House the day before with pneumonia, his brief illness was made fatally serious by the heart condition which had forced him to take special leave a few years ago and had restricted his activities since.

Professor Cox was born in Lewiston, Maine, August 25, 1889, and was graduated from Bates College in 1911. Shortly thereafter he began his teaching career at the Plymouth (N. H.) High School. Here began his lifelong friendship with Robert Frost, who was teaching at the Plymouth Normal School. He did graduate work at the University of Illinois and Columbia, where he began his college teaching in 1919. He became assistant professor at the University of Montana in 1920 and remained there for six years until called to Dartmouth as assistant professor in 1926. He was promoted to full professor in 1939.

Professor Cox's courses in creative writing won him a devoted following among Dartmouth men, many of whom went on as professional writers. He found time for creative writing of his own. He was the author of The Teaching of English, Avowals and Ventures in 1928, Robert Frost:"Original Ordinary Man" in 1929, and Indirections for Those Who Want to Write in 1947. He also was co-editor of two sets of Prose Preferences, which have been widely used in American colleges.

Professor Cox served in the first World War as a second lieutenant. In 1917 he was married to Alice Macy Ray of Waverley, Mass. who survives him with their two sons, Arthur M. Cox '42 of Washington, D. C., and Wendell H. Cox '53; their daughter, Mrs. Joaquin J. Vallerino ('43) of Panama City, Panama; and six grandchildren.

A memorial service was held in Rollins Chapel on Sunday afternoon, January 6. Robert Frost read his lyric Come In; the following tribute was read by Stearns Morse, Professor of English and Dean of Freshmen, a close friend for many years.

SIDNEY COX 1889-1952

A quarter century ago Sidney and Alice Cox came to Dartmouth from Montana, where he had been teaching, to put new roots down in the Hanover plain. He had come bruised by a bitter experience: good and well-meaning people had misunderstood his championship of the right of his students to write and print what they wanted to write and print even if it was sometimes offensive to good and well-meaning people. We are glad to think that they found healing here; that the new roots took nourishment from our beneficent earth; that Sidney kept on growing to be the great teacher he was and, we know, still is.

Many influences whose sum we cannot tally went into the making of this man who was our friend. He spent his boyhood in the New England towns and villages among people who worked hard for their livelihood and were content with simple pleasures. He was brought up in a Christian parsonage: the outward forms of Christianity he sloughed off in his later life; but what is essential in it remainedthe burning individualism, the moral intensity. He read greedily; books were to him living persons, the great companions of our American and English heritage. He received his formal education over the years at Bates, the University of Illinois and Columbia, eagerly receptive to the impress of good teachers. In his early teaching experience at the Plymouth High School he came under the lasting influence of the greatest teacher of them all. In 1917 he married and served a term of soldiering as a lieutenant in the first World War. After the war came the years of teaching and the generations of students who gave him strength as he gave strength to them.

But what most of all made him a great teacher was the spark within him which grew to an electric flame, its heat and light generated perpetually by the warmth and frictions of his personal relationships. To burn always with a hard, gem-like flamethis was his desire, not simply in Pater's sense, for the moment's sake, but for the illumination of his life with meaning.

I remember he asked me once in his first year here about a boy in my writing class whom he had known in Montana. "Is he stretching himself?" This question was characteristic of Sidney Cox, characteristic of his continually living on the stretch, of the electric tension which irritated some but which also created an excitation in his students impelling them to make more of themselves than they might otherwise have made. It must be admitted that some of them were pulled by his tension out of their natural orbits; but I am sure that when they had passed beyond his reach they were, if ever so little, more honestly themselves than they had been before their experience of him.

For he taught them both by precept and example the hardness of choices in a complex world; an impatience with mediocrity, though he himself was keenly aware of the stretches of mediocrity all of us have in our lives. He taught them the necessity of resistance if one is to preserve the integrity of the self against the pulls and pressures of compliance and convention. For this was his basic creed: to be oneself; this was what he meant by his demand for honesty. For him it was no mere glib word. He was not satisfied with the easy phrase, the parroting of others, the superficial summation. In talking with you he wanted you to be very sure you knew what he meant; in return he demanded more than the surface of yourself. For him every relation must be a true relation.

This integrity was at the center of his writing: if therefore his prose was sometimes gnarled and tortured it was never banal. I know that he was sometimes disappointed that his writing did not reach a larger audience. But if he knew the necessity of resistance he knew also the necessity of acceptance. If his personality did not reach its fullest expression in his writing, it surely did in his teaching. Of the hundreds of students—the dull, the mediocre, the keen, the brilliant—who sat in his classes, came to his fireside, talked with him in his study, walked with him over the hills, none, I am sure, will ever forget him. For to him each of them was a person in whom was some spark to be fanned to shining, however feebly. Many of them have attained the reputation as writers he failed to attain. But however far away from him they have gone, I can see them glancing back at him over their shoulders and asking themselves if what they are writing is false or true.

I see that perhaps I have given an impression of Sidney Cox as of one, like Jacob, wrestling with an angel; of a man to whom one might say, now that the end has come: rest, rest, perturbed spirit. But it is not thus that we must take leave of him. Intense he was, but it was a happy intensity: he was happy in his marriage, in his children, in his work, in his friends. He had a happy six months in England last year with his wife, absorbing to the full ancestral and literary associations. When some time ago the doctors prescribed a sharp drop in his voltage, he accepted their verdiet cheerfully so that his last years with us have been lambent and serene.

Now all that is mortal of him is about to be returned to the earth; all that is immortal of him shines on. Like one other of his friends and ours who has recently left us he has gone forth on the open road, he belongs to the great Companions, "the swift and majestic men."

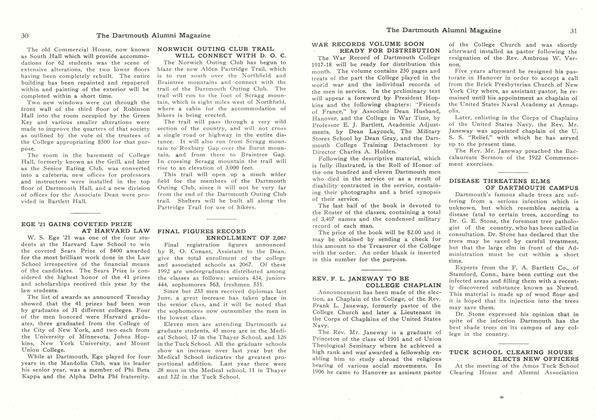

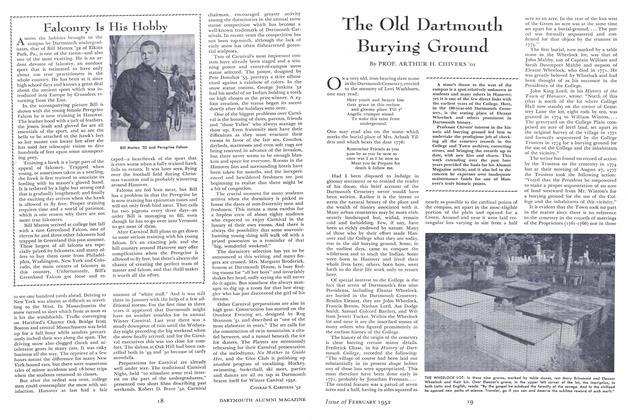

PROF. SIDNEY COX

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

February 1952 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, RICHARD P. WHITE -

Article

ArticleThe Old Dartmouth Burying Ground

February 1952 By PROF. ARTHUR H. CHIVERS '02 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1950

February 1952 By ENS. SCOTT C. OLIN, USN, SIMON J. MORAND III -

Article

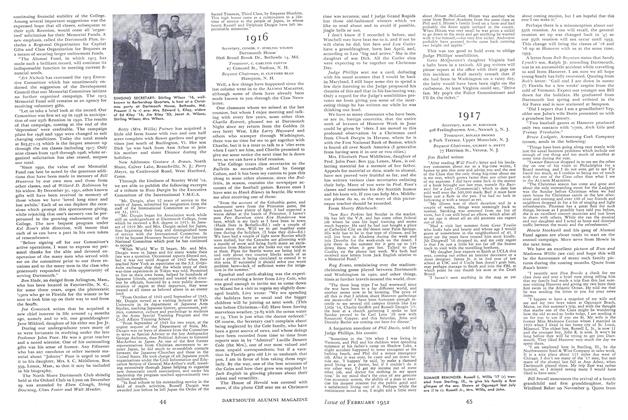

ArticleThe First (and Only) College Balloon Race

February 1952 By JOHN PEARSON '11 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

February 1952 By WILLIAM ANDRES, EDWIN C. CHINLUND, JACK D. GUNTHER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

February 1952 By KARL W. KOENIGER, DONALD BROOKS, GILBERT N. SWETT