THE position of the poet in our time is a paradoxical one, in some ways bitter for the poet. He speaks of the central issues of society from a position out on the periphery of society. He aims at fullness and intensity and precision of statement, yet too often he is read casually and carelessly by readers who are content to grasp an easy fraction of what he is saying. His concern is with the common experience and the common potential of all men, but few men pay him any heed, although what he says is urgently important to them. For such reasons as these, it is a happy duty, always, to acknowledge a poet and his achievement.

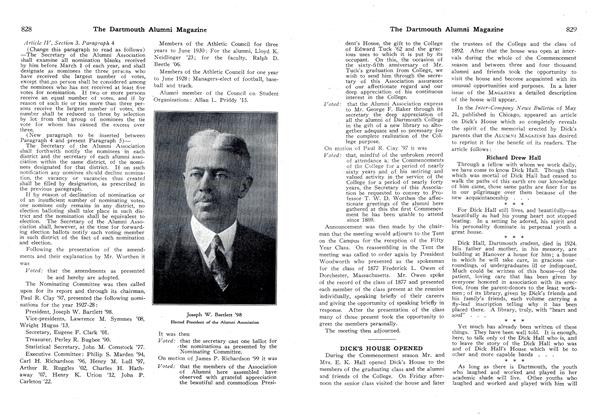

Richard Eberhart is Dartmouth's most distinguished poet. He has been recognized as"one of the very best of his generation" by critics both here and in England, and he was honored recently with two impressive awards, Poetry Magazine's Harriet Monroe Memorial Prize and the Shelley Memorial Prize of the Poetry Society of America., Yet one wonders how many of his classmates in the Class of '26, how many of his brothers in Alpha Delta Phi, how many men of Dartmouth have followed his steady growth in poetic stature through his eight volumes since 1930, or how many have read the culminating volume, his Selected Poems, published this year. Those who do know his work (he has loyal Dartmouth followers whose numbers are increasing) will be proud to read here a new poem, paired with a familiar one, for each new publication on his part is a reason for pride to Dartmouth readers.

The poetry of Richard Eberhart is not easy poetry, but all its difficulty is honest difficulty, there because he tackles the difficult themes. He is not an obscurantist,

nor a private performer nor a closet virtuoso. A great range of experience is drawn into his poems, even spatially great. The mid-west is there: Eberhart was born in Minnesota and remembers a mid-western youth. New England is there, the turning of the New England seasons over her hills and mountains, New Hampshire's sounds and silences, the impressions we all keep who have known this country. The far places are there, too. His poems sometimes reflect the gentle English land he knew at Cambridge, where, at St. John's College, he studied for his M.A. in the years 1927 to 1929. Sometimes they speak of Europe, the places that felt the "fury of aerial bombardment," or of the Pacific, the islands where, in the agony of capture, men learned the "brotherhood of men." After graduation from Dartmouth Eberhart sailed round the world on a merchant ship, and during the war years he served as an officer in the U.S. Naval Reserve. And the familiar nearby places, Cambridge, Harvard Square and Mt. Auburn, appear in his work as well. He was a graduate student at Harvard in 1932 and 1933 and now has returned to live with his wife and children in Cambridge. All he has seen and done he translates into his verse.

But the spatial range of Eberhart's poetry, its horizontal reach over lands and places, is really only incidental. Of first importance is its vertical penetration into human experience. It is a penetration both upwards and downwards. His poetry is fully aware of man's earthiness and his mortality. But it is aware also of man's powers of flight. Eberhart speaks often in the exalted tones of the true visionary. His poems, at their best, have the fiery authority that comes from an intuitive knowledge of the heights to which the spirit can aspire.

"To read the spirit was all my care and is," he says. Reading thus, Eberhart has learned that hardest lesson, that the truth that matters most is always contradictory.

Those who suffer see the truth; it has Murderous edges . . .

But the fact that truth is a cutting blade has not frightened or deterred him. He found it necessary to his poetry to live with opposites; to reject them would be to be false to his chosen trade.

All things by opposites go, Truth has there his lease.

This perception immediately ruled out the easy answers to the difficult questions, all the little appeasements of the ego, the indulgences and the sentimentalities. The trouble with them, of course, is that they are half-true at best, that they deny their opposites and lack the murderous edges. The real difficulty of Eberhart's poetry lies in its honesty. Paradox is never easy, but his vision drives him always into paradox and he has not shied back from it.

In these times of noisy assertiveness, paradox is suspect, unfashionable. The bold headlines, the cocksure commentators, the analysts of black and white have conditioned us as readers to distrust the complex and the contradictory. It would be so nice if the unsimple were untrue. Yet there is a test of truth we can always make, inherent in language itself. It is of the nature of language that it can underwrite truth, by its very sound and texture, or conversely expose untruth. How often we find, on examination of the loud simplification, that its words have a hollow ring, a false sound. The same test will work for honesty like Eberhart's. This language rings true. The vividness and strength of the words themselves, their toughness and hardness, their tone and rhythm notarize the emotion and the wisdom they contain. There are men, many in New England, whom we believe simply because of their tone of voice. So, too, there are poets, Eberhart is one, whom we believe because of the tangible honestry of their diction, however disturbing and paradoxical their words may be.

The last poem in Eberhart's SelectedPoems is a narrative of the experiences of one captured in the Philippines, a prisoner of war through the four nightmare years between Corregidor and liberation. The poem ends, after the "planes came over parachuting packages," and "greedy as children, we ate chocolate until we were sick," with the wish to "forget the fever and famine, the fierceness of visions," the whole long horror of the experience. The last lines are these:

And yet I know (a knowledge unspeakable) That we were at our peak when in the depths, Lived close to life when cuffed by death, Had visions of brotherhood when we were broken, Learned compassion beyond the curse of passion, And never in after years those left to live Would treat with truth as in those savage times, And sometimes wish that they had died As did those many crying in their arms.

As a conclusion this may be disturbing, contradictory, the paradox of man's height and depth together. But its language is clean and honest. Its rhythms are those of confident speech, and it convinces us it can be trusted. Eberhart's poetry is all like that. For such reasons as these, it is a happy privilege, in a Dartmouth publication, to acknowledge Richard Eberhart and his achievement.

RICHARD EBERHART "26

ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleDeaths

June 1952 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

June 1952 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Article

ArticleThe Cold War and Liberal Education To a Father From a Dean

June 1952 By STEARNS MORSE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

June 1952 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, EDWIN C. CHINLUND, GEORGE B. REDDING -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

June 1952 By HERBERT H. HARWOOD, H. DONALD NORSTRAND, ANDREW J. O'CONNOR -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

June 1952 By CONRAD S. CARSTENS '52

Article

-

Article

ArticleNEW QUARTERS SOUGHT BY THE GRADUATE CLUB

NOVEMBER, 1926 -

Article

ArticleDICK'S HOUSE OPENED

AUGUST, 1927 -

Article

ArticleHear the Echoes Ring (Or Green Corn)

APRIL 1970 -

Article

ArticleMasthead

MARCH 1972 -

Article

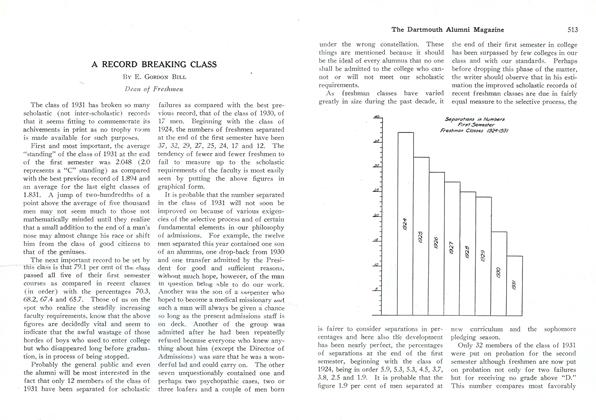

ArticleA RECORD BREAKING CLASS

APRIL 1928 By E. Gordon Bill -

Article

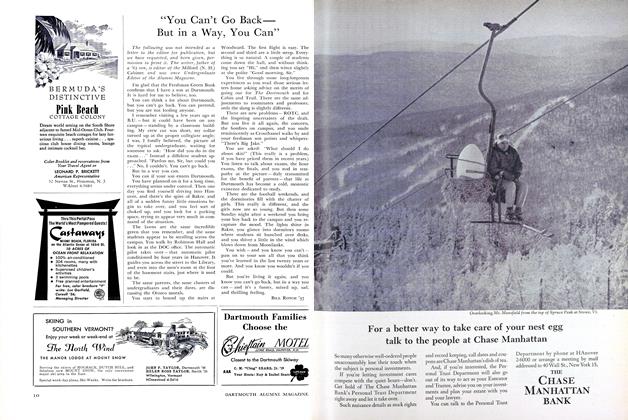

Article"You Can't Go Back — But in a Way, You Can"

February 1960 By William B. Rotch ’37