The awarding to President Eisenhower of an honorary Doctorate of Laws at Commencement time last June has occasioned an amount of interest in the possible Dartmouth association of his predecessors in office.

Indeed, there have been in all a full half-dozen other Presidents of the United States who have held honorary degrees from the College, and, in addition, several who seemingly have almost received one.

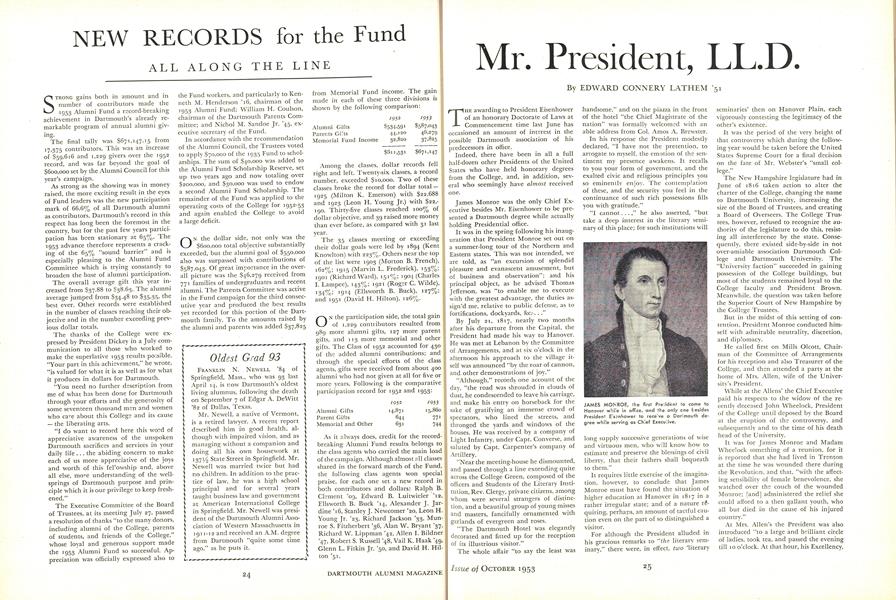

James Monroe was the only Chief Executive besides Mr. Eisenhower to be presented a Dartmouth degree while actually holding Presidential office.

It was in the spring following his inauguration that President Monroe set out on a summer-long tour of the Northern and Eastern states. This was not intended, we are told, as "an excursion of splendid pleasure and evanascent amusement, but of business and observation"; and his principal object, as he advised Thomas Jefferson, was "to enable me to execute with the greatest advantage, the duties assign'd me, relative to public defense, as to fortifications, dockyards, &c...."

By July 21, 1817, nearly two months after his departure from the Capital, the President had made his way to Hanover. He was met at Lebanon by the Committee of Arrangements, and at six o'clock in the afternoon his approach to the village itself was announced "by the roar of cannon, and other demonstrations of joy."

"Although," records one account of the day, "the road was shrouded in clouds of dust, he condescended to leave his carriage, and make his entry on horseback for the sake of gratifying an immense crowd of spectators, who lined the streets, and thronged the yards and windows of the houses. He was received by a company of Light Infantry, under Capt. Converse, and saluted by Capt. Carpenter's company of Artillery.

"Near the meeting-house he dismounted, and passed through a line extending quite across the College Green, composed of the officers and Students of the Literary Institution, Rev. Clergy, private citizens, among whom were several strangers of distinction, and a beautiful group of young misses and masters, fancifully ornamented with garlands of evergreen and roses.

"The Dartmouth Hotel was elegantly decorated and fitted up for the reception of its illustrious visitor."

The whole affair "to say the least was handsome," and on the piazza in the front of the hotel "the Chief Magistrate of the nation" was formally welcomed with an able address from Col. Amos A. Brewster.

In his response the President modestly declared, "I have not the pretention, to arrogate to myself, the emotion of the sentiment my presence awakens. It recalls to you your form of government, and the exalted civic and religious principles you so eminently enjoy. The contemplation of these, and the security you feel in the continuance of such rich possessions fills you with gratitude."

"I cannot...," he also asserted, "but take a deep interest in the literary seminary of this place; for such institutions will long supply successive generations of wise and virtuous men, who will know how to estimate and preserve the blessings of civil liberty, that their fathers shall bequeath to them."

It requires little exercise of the imagination, however, to conclude that James Monroe must have found the situation of higher education at Hanover in 1817 in a rather irregular state; and of a nature requiring, perhaps, an amount of tactful caution even on the part of so distinguished a visitor.

For although the President alluded in his gracious remarks to "the literary seminary," there were, in effect, two 'literary seminaries' then on Hanover Plain, each vigorously contesting the legitimacy of the other's existence.

It was the period of the very height of that controversy which during the following year would be taken before the United States Supreme Court for a final decision on the fate of Mr. Webster's "small college."

The New Hampshire legislature had in June of 1816 taken action to alter the charter of the College, changing the name to Dartmouth University, increasing the size of the Board of Trustees, and creating a Board of Overseers. The College Trustees, however, refused to recognize the authority of the legislature to do this, resisting all interference by the state. Consequently, there existed side-by-side in not over-amiable association Dartmouth College and Dartmouth University. The "University faction" succeeded in gaining possession of the College buildings, but most of the students remained loyal to the College faculty and President Brown. Meanwhile, the question was taken before the Superior Court of New Hampshire by the College Trustees.

But in the midst of this setting of contention, President Monroe conducted himself with admirable neutrality, discretion, and diplomacy.

He called first on Mills Olcott, Chairman of the Committee of Arrangements for his reception and also Treasurer of the College, and then attended a party at the home of Mrs. Allen, wife of the University's President.

While at the Aliens' the Chief Executive paid his respects to the widow of the recently deceased John Wheelock, President of the College until deposed by the Board at the eruption of the controversy, and subsequently and to the time of his death head of the University.

It was for James Monroe and Madam Wheelock something of a reunion, for it is reported that she had lived in Trenton at the time he was wounded there during the Revolution, and that, "with the affecting sensibility of female benevolence, she watched over the couch of the wounded Monroe; [and] administered the relief she could afford to a then gallant youth, who all but died in the cause of his injured country."

At Mrs. Allen's the President was also introduced "to a large and brilliant circle of ladies, took tea, and passed the evening till 10 o'clock. At that hour, his Excellency, and the party at Mrs. Allen's were received in elegant style by Mrs. Brown [the wife of the President of the College], and passed the evening in cheerfulness and conviviality, heightened by music suited to the occasion."

Thus, as the Dartmouth Gazette reported, "Throughout the whole scene the utmost harmony and concord prevailed, and never have we witnessed an occasion when the countenances spoke more clearly, that the heart was glad."

At seven the next morning the President was up and on his way once more, ready-but without any great enthusiasm - to meet the new surges of public jubilation that would greet him as he continued his journey.

The following week's issue of the Gazette relates that for two days the Presidential route could be "ascertained from this village (Dartmouth) by the roar of distant cannon, echoing among the green hills of Vermont." And the local editor adds with evident tongue in cheek, "The patriotic Green Mountain boys seem equally prodigal of their powder, whether it be burnt in greeting their friends or foes."

James Monroe had come and he had gone, and yet there is no evidence of any mention of honorary degrees. Harvard had made its LL.D. award on the spot when the President visited Cambridge. In Hanover, however, there was a necessary delay until the Commencement season in late August when the Trustees gathered for their meeting. At that time not only the College, but the University as well, voted Mr. Monroe, in absentia, into their honorary fellowship as a Doctor of Laws.

Both Boards appear to have voted their degrees on the same day, August 26, 1817, but since the College Commencement exercises were held two hours earlier than those of the University, and as degrees are actually conferred at these exercises, rather than at the time they are voted, it would seem that the College's LL.D. was bestowed upon Monroe first.

The priority, however, is a question of little importance, since the Supreme Court a year and a half later declared unconstitutional that legislation of the state which had altered the College charter and, in essence, created the University. And it may be presumed although perhaps not so readily proved to the legally minded that this action also voided all acts of the University, dispatching Doctor Monroe's "University degree" into the realm of the non-existent.

ALTHOUGH he was the first Chief Executive to come to Hanover while in office and the only other besides President Eisenhower to receive a degree during such a period, Monroe was not the earliest of the Presidents of the United States to have a Dartmouth degree.

John Adams was the first, having been granted an honorary LL.D., in absentia, in 1782, while Minister Plenipotentiary to the United Netherlands, some four and a half years before he entered upon the Presidency.

The circumstances, however, surrounding the making of this award to Adams at this particular time seem to suggest that the motives of John Wheelock and his colleagues of the Board may not have been of the most disinterested character.

At the same meeting in September, 1782, at which John Adams' degree was voted, the Trustees resolved, "That this board esteem it expedient that application be made to France and other Kingdoms and States in Europe for benefactions to this Institution"; and, accordingly, provisions were made to send representatives abroad for this purpose.

It is, moreover, apparent from a draft of the minutes of the meeting that prior to passing the above resolution, the Trustees wrestled with some measure of indecision in the matter of who should be the recipients of its Doctorates of Laws that year. The Hon. Thomas McKean, member of Congress from Delaware and late president of that body, was agreed upon. Then the names of three distinguished and influential French gentlemen were carefully set down, only to be crossed out forthwith; and in their places were substituted seemingly by virtue of better satisfying the same purpose the names of John Adams and the French Minister to the United States.

This evidence notwithstanding, there is, of course, no one today, after the passage of 171 years, who would care to suggest too strongly that possibly there can be discerned in this action by the venerable Board some semblance of ulterior motive or a calculated and unworthy courting of favor on their part against a foreseeable time of need. Such a suggestion would be outrageous! (At any rate, even a casual student of the finances of the College at this period could easily make a case for striking out the word "unworthy" in any such charge.)

It should suffice to observe that an able American diplomat in the process, as it developed, of rising to the Presidency was duly honored by the College in the period of his ascendancy adding only, perhaps, by way of an historical footnote, that the following summer found John Wheelock and his brother James traveling about Europe soliciting benefactions, armed, among other credentials, with an appropriate number of epistles introductory from the pen of John Adams Esq., Dartmouth LL.D. After the award to Monroe in 1817, no other President was similarly honored until 43 years later, when, in iB6O, for the first and only time an ex-President of the United States was taken into the honorary Dartmouth fellowship.

During the intervening time, however, President Andrew Jackson, while making his Eastern tour in the summer of 1833, was requested by President Nathan Lord to include Hanover in his itinerary in order that the faculty and students might pay him their respects. But like Washington, Jefferson, and Madison while on their inspectional tours of the region, the Tennessean did not penetrate to what Doctor Lord aptly styled the "retired residence" of the inhabitants of Hanover. Ill and exhausted, he collapsed, in fact, at Concord and was returned in a critical state to Washington.

Whether, had he actually come to the College, he would have won for himself an honorary degree as Monroe had done before him cannot be surmised. It may, however, be pointed out that Harvard for its part did feel it necessary to follow the precedent that had been set with Mr. Monroe, and feted "Old Hickory" in precisely the same manner although greatly to the objection of some, including John Quincy Adams, the man from whom Jackson had wrested the White House.

Ideal weather ushered in the Commencement season of iB6O at which ex-President Franklin Pierce was present to receive in person an honorary Doctorate of Laws, little more than three years after leaving the White House.

The festivities began on Tuesday, July 24, with the traditional Class Day exercises; and in the evening the students, accompanied by a band, serenaded the former Chief Executive, who "acknowledged the compliment, in a graceful speech, which elicited frequent and hearty applause."

On Wednesday the featured event was the eulogy on Rufus Choate pronounced by the Hon. Ira Perley of Concord. It was, however, evidently pronounced with insufficient volume, for the Portsmouth Journal reports it as having been "very interesting throughout to those who could hear it, who were only a minority of the audience, as the tone was much too low."

At ten o'clock on the morning of the 26th the Commencement exercises got under way. During the four-and-half-hour ceremony, no fewer than 25 seniors "drawn from the class by lot" discoursed on subjects ranging from "The Dangers of Excess" to "Benefits Conferred Upon Commerce by American Science," and "The Moral Element in Political Revolutions."

Finally, with the last peal of undergraduate oratory suitably celebrated by the musicians, the honorary degrees were conferred, and Franklin Pierce, the only New Hamshireman to become President of the United States, received his Dartmouth LL.D. Then, after the final musical selection had been played, and the closing prayer said, adjournment was made to the Dartmouth Hotel for a "bountiful repast" - undoubtedly most welcome by that hour.

(This, it may be observed, had not been Pierce's first visit to Hanover, for we know of at least one other which was made over fourteen years earlier, when, in March of 1846, he came to speak in the meeting house "on subjects of great political interest to every citizen.")

One of the most interesting instances of Dartmouth's connection with Presidents of the United States in the matter of honorary degrees is the case of one President who was deprived of such an award: Abraham Lincoln.

Nathan Lord, who for 35 years had guided wisely and well the government of the College, was at that time still its President. In the late forties he had accepted, and subsequently espoused with vigor, the thesis of the divine ordination of slavery. It was a position which could hardly be calculated to make its proponent popular in the North, especially as the troubled war years of the early sixties came on.

But Nathan Lord was a man with the courage of his convictions. His stand was theological, not political, and he would not be squelched by the violent. attacks that were soon levelled upon him. He felt the war and the abolition movement to be morally wrong, and he was not afraid to say so.

The memorable events of the Trustees meeting in July, 1863, are best told in Lord's own words: "It was proposed, in the Board," he wrote to his nephew, "that but one Honor should be conferred this year, and that the Degree of LL.D. on AbrahamLincoln. Resolved that the College should not be so disgraced while I lived in it I joined Judge Eastman strenuously in opposing it. My vote made a tie and spoiled the trick."

Later at this same meeting the Trustees considered the resolutions forwarded by the Merrimack County Conference of Congregational Churches, which stated that "in our opinion it is the duty of the Trustees of the College to seriously inquire whether its interests do not demand a change in the Presidency...." While declaring a "sincere regard" for Doctor Lord, the Conference felt that the College's welfare was "greatly imperiled by the existence of a popular prejudice against it arising from the publication and use of some of his peculiar views touching public affairs...."

Although unwilling to consider the removal of the President, the Board did vote to go on record as both supporting the government in its prosecution of the war and as taking a positive position in opposition to slavery. At this Nathan Lord asked permission to withdraw from the meeting for a short time, and upon returning he read and tendered his unequivocal, though cordially worded, resignation.

He could not see his College honor Lincoin, the living symbol of the whole movement against slavery. He prevented it! And he would not have his personal freedoms questioned nor condone the action of the Board in officially endorsing what he believed to be the evil course of the federal government. He preferred to resign rather than acquiesce. He went into retirement "as free and happy as a bird, except for regret at seeing Dartmouth prostituted to a vile idolatry."

One wonders, of course, why the Trustees did not at the very next Commencement vote Mr. Lincoln the degree which Nathan Lord had prevented them from granting in 1863. The reason would seem probably to have been that, as was proper and fitting, the Board chose to honor Lord himself at the Commencement following his resignation with the Doctorate of Laws of the institution he had served so long and faithfully. Under the circumstances it would, naturally, have been unthinkable also to have conferred a degree upon President Lincoln at the same time. And by Commencement time of 1865 Abraham Lincoln was dead.

In May 1866, President Asa Dodge Smith wrote to Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant asking that he attend the Dartmouth Commencement two months hence. The governor of the state, an ex officio Trustee of the College, agreed to deliver the invitation to the general and to do what he could to secure its acceptance. But it would appear that New Hampshire's chief executive of that day had little or, at least, insufficient influence with this military hero soon to become President of the United States, and Grant declined due to "pressure of public business."

The text of Doctor Smith's letter is not available, but, at any rate, there would seem little doubt that had the General come he would have been appropriately honored by the College with a degree.

The 1866 Commencement, nonetheless, was not without the presence of a famous soldier, for "The Great Marcher," William Tecumseh Sherman, came to see his nephew graduated and was himself awarded an honorary LL.D.

It is interesting to note that President Smith had known of Major General Sherman's intention of coming for nearly two months before he sent his invitation to Grant, and he seems, therefore, to have been desirous of having a truly splendorous military Commencement. He could not have been disappointed, however, even without "The Hero of Appomattox." Sherman was evidently superb, outshining even the august presence of the Chief Justice of the United States, Salmon P. Chase, of the Dartmouth Class of 1826, several times a leading contender for Presidential nomination.

Three years later both Sherman and Chase were back again to help celebrate Dartmouth's Centennial, and there is even evidence that at one time at least it was expected that Grant, now President, might possibly attend. He did not.

In March, 1876, during the Hayes-Tilden campaign, Congressman James A. Garfield came to Hanover under the auspices of the undergraduate Republican Club. The future Chief Executive made a well-received speech to a surprisingly large, and, as he himself termed it, "fine intellectual audience." The following year the victor in that campaign, President Rutherford B. Hayes, was greeted at the Norwich depot by the faculty and students of the College, but he apparently did not cross the river or, perhaps, even leave the rail-road station.

After the award to Franklin Pierce no person destined to fill the Presidency received an honorary Dartmouth degree until 1909, nearly fifty years later. In October of that year there assembled at the College what was probably the most distinguished gathering of academicians ever held on Hanover Plain.

It was the inauguration of Ernest Fox Nichols as tenth President of the College, and delegates came from all over the nation. There were well over half a hundred college and university presidents alone, and included in this number as one of the speakers was Princeton's President Wood-row Wilson.

Wilson, who a year later was to resign his Princeton post to enter the race for the New Jersey governorship, was also among those awarded honorary degrees at the inauguration ceremonies. In presenting the Doctorate of Laws, President Nichols cited him as "lawyer, historian, student of politics, man of great strength of purpose, who is steadfastly forging the college that ought to be out of the college that now is."

Woodrow Wilson was soon, of course, to increase to four the number of Chief Executives having Dartmouth degrees, for within scarcely more than three years' time he was elected to the Presidency, the first Democrat to win that office in twenty years.

Of the five Presidents who appear to have been in Hanover at some time during their terms, William Howard Taft, whom Wilson defeated, is the only one who never received a degree from the College. (Monroe, of course, had come just prior to being awarded his; Eisenhower, in conformance with the later-established tradition requiring the presence of degree recipients, was here at the time his was conferred; and Wilson and Franklin Roosevelt, both of whom came to Hanover while serving in the Presidency, had received their degrees before entering the White House.)

In October 1912, at the invitation of President Nichols, President Taft and his party interrupted a "flying automobile trip from Bretton Woods to Keene" long enough to take lunch with Doctor and Mrs. Nichols and make a brief address intended primarily for the undergraduates.

Being behind in his schedule, the President was "compelled to rush his machine over the roads to Hanover," and upon his arrival went directly to the Nichols residence for the luncheon, which according to plan preceded the speech.

"Owing to the lack of time," states The Dartmouth, and the weakened condition of President Taft's voice, his address was not made in Webster Hall as announced, but from his automobile in front of the building."

One remark of the jovial Mr. Taft may well have drawn a hearty chuckle from his audience. I am," he said, "a Yale man. I am endeavoring to bestow upon you a great compliment when I say that Dartmouth is more like Yale than any other American college. I hope that you will consider this a compliment."

Following Woodrow Wilson, Herbert Hoover was, in 1920, the next "President-to-be" to receive an honorary LL.D. from the College. In being presented the degree at the Commencement exercises, he was cited by President Hopkins as "eloquent spokesman of a great nation's better self, an exponent to stricken peoples of its practical idealism; keen in insight and ample in talent for the analysis of domestic problems; translator of great personal opportunity into terms of invaluable public service."

At the Commencement luncheon following the ceremonies, Doctor Hoover responded with a short address to the thunderous ovation which he was given. "These are distinctions," he is reported as having said, "conferred from men's hearts, and far beyond any that can come from governments."

And referring in a jocular manner to the contemporary political scene he declared, "I have been in relief work for five years; I have given relief to the whole world, but it does not compare with the relief the Chicago convention gave me two weeks ago when they failed to nominate me for the Presidency." (This proved, of course, to be only temporary relief, albeit of some eight years' duration.)

President Hoover's successor in the Executive Mansion in Washington was also his successor in acquiring an honorary degree from Dartmouth while on his way to the Presidency.

(Calvin Coolidge, it may be pointed out, visited town in 1922 while still Vice-President to speak to a gathering of New Hampshire and Vermont Republicans, and following this gave a talk in Webster Hall to the undergraduates; but he was never honored by the College with a degree.)

In 1929, Franklin D. Roosevelt, then Governor of New York, took time out from his activities as Chief Marshal during his twenty-fifth reunion at Harvard to come to Hanover to receive an honorary Doctorate of Laws from Dartmouth, as the College graduated on a warm and sticky eighteenth of June the largest class in its history to that time - 439 strong.

Due to his disability Governor Roosevelt was not able to take part in the academic procession. His car was driven to the east rear door of Webster Hall, where a

special ramp had been constructed to make it possible for him to ascend more easily to the stage. Similar arrangements had also been made for him at the Inn. And at the gymnasium a series of ramps and handrails had been put in place going all the way to the second floor, where he was to speak at the alumni luncheon.

President Hopkins' citation in conferring Dartmouth's LL.D. on the man destined to be the only four-term President of the United States reads in part: "Repre-sentative of qualities of citizenship which make a nation great; liberal in theory and progressive in action; unselfish in the acceptance of great responsibilities and actuated by generous ideals; to you in remarkable degree have been confided the admiration and confidence of your constituents and, as well, of the American people at large.... Fine in cultural appreciation, intellectual in aptitude, democratic by instinct, and courageous whether in meeting the machinations of political maneuvers or the harsh exigencies of suddenlyimposed physical adversity, you are one whom Dartmouth has delight in associating with its fellowship...

With Franklin Roosevelt we have come to the sixth and last of the names on the list of President Eisenhower's predecessors who have held Doctorates of Laws from the College.

It is, of course, impossible to predict what the record of the future will be: when there will be another Chief Executive with an honorary Dartmouth degree, and who that will be. It is interesting to note, however, that the odds seem to favor his receiving his degree like Adams, Wilson, Hoover and Roosevelt prior to becoming President. This may, in fact, already have happened!

JAMES MONROE, the first President to come to Hanover while in office, and the only one besides President Eisenhower to receive a Dartmouth degree while serving as Chief Executive

FRANKLIN PIERCE, who received an honorary LL.D. in 1860, is the only President so honored by the College after he had left the White House.

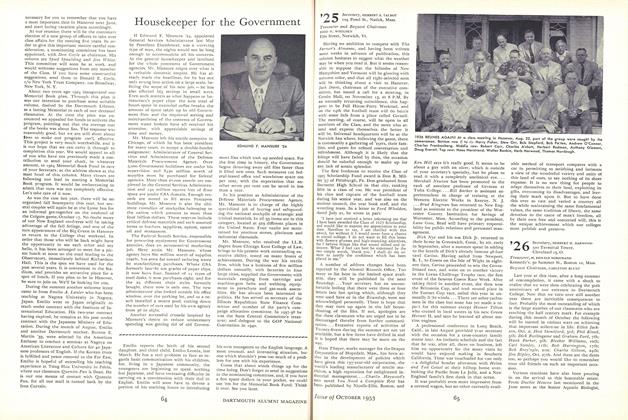

HERBERT HOOVER shown in 1920, the year he received his Dartmouth LL.D., with Hundley N. Spaulding (center), later Governor of New Hampshire, and President Hopkins at Spaulding's office in Manchester, N. H., before an American Relief Administration banquet.

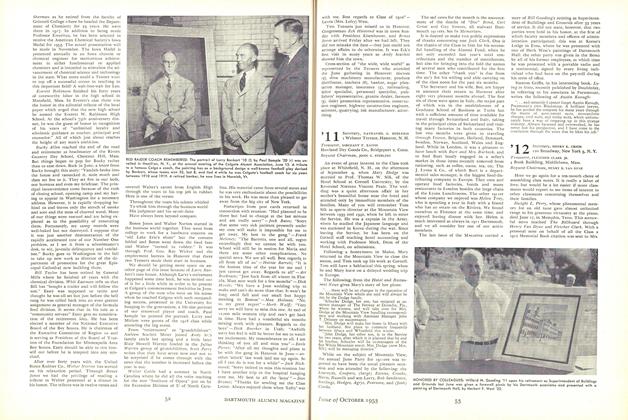

FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT, honored at the 1929 Commencement while still serving as Governor of New York, shown with President Hopkins.

WOODROW WILSON, then President of Princeton, received his LL.D. in 1909 at the inauguration of President Ernest Fox Nichols.

PRESIDENT EISENHOWER RECEIVING HIS DARTMOUTH LL.D. LAST JUNE

PRESIDENT TAFT visited Hanover in 1912 while in office but not to get an honorary degree. He is shown with President Nichols, his luncheon host.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

October 1953 By ERNEST H. FARLEY, W. CURTIS CLOVER, RICHARD P. WHITE -

Article

ArticleThe Faculty

October 1953 By Harold L. Bond '42 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

October 1953 By HERBERT H. HARWOOD, H. DONALD NORSTRAND, CARLETON BLUNT -

Class Notes

Class Notes1912

October 1953 By HENRY K. URION, FLETCHER CLARK JR., HENRY B. VAN DYNE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1948

October 1953 By FRANCIS R. DRURY JR., JOHN S. FENNO -

Class Notes

Class Notes1910

October 1953 By RUSSELL D. MEREDITH, JESSE S. WILSON, LELAND POWERS

EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51

-

Article

ArticleDaniel Webster's College Days

October 1952 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51 -

Feature

FeatureChronicler of Gettysburg

May 1958 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51 -

Feature

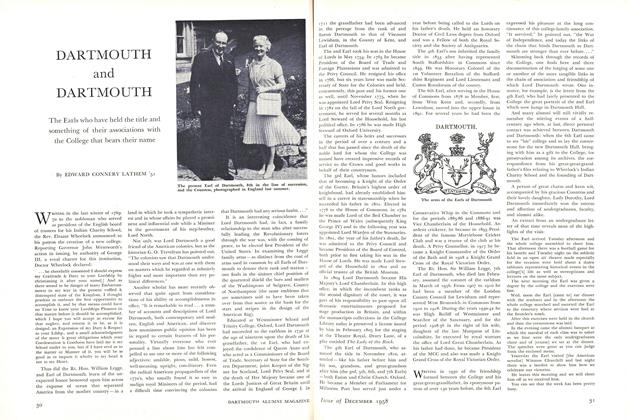

FeatureDARTMOUTH and DARTMOUTH

DECEMBER 1958 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51 -

Feature

Feature...AND MANY DARTMOUTH YESTERDAYS

March 1962 By Edward Connery Lathem '51 -

Feature

FeatureAND MANY DARTMOUTH YESTERDAYS

FEBRUARY 1963 By Edward Connery Lathem '51 -

Feature

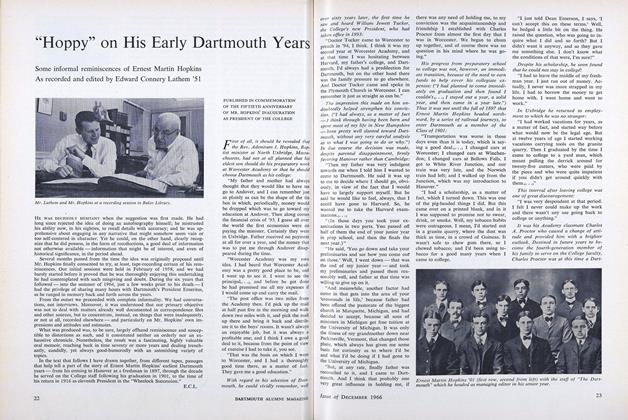

Feature"Hoppy" on His Early Dartmouth Years

DECEMBER 1966 By Edward Connery Lathem '51