Robert Frost '96, whose 85th birthday is observed this month, recalls some incidents of his undergraduate period at Dartmouth

EXCERPTS FROM AN INTERVIEW

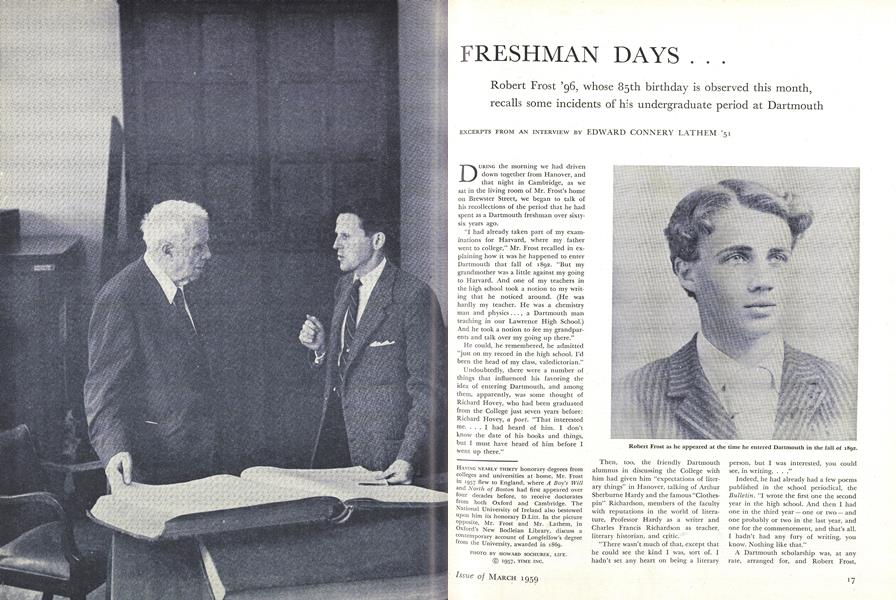

DURING the morning we had driven down together from Hanover, and that night in Cambridge, as we sat in the living room of Mr. Frost's home on Brewster Street, we began to talk of his recollections of the period that he had spent as a Dartmouth freshman over sixtysix years ago.

"I had already taken part of my examinations for Harvard, where my father went to college," Mr. Frost recalled in explaining how it was he happened to enter Dartmouth that fall of 1892. "But my grandmother was a little against my going to Harvard. And one of my teachers in the high school took a notion to my writing that he noticed around. (He was hardly my teacher. He was a chemistry man and physics . . . , a Dartmouth man teaching in our Lawrence High School.) And he took a notion to see my grandparents and talk over my going up there."

He could, he remembered, be admitted "just on my record in the high school. I'd been the head of my class, valedictorian."

Undoubtedly, there were a number of things that influenced his favoring the idea of entering Dartmouth, and among them, apparently, was some thought of Richard Hovey, who had been graduated from the College just seven years before: Richard Hovey, a poet. "That interested me. ... I had heard of him. I don't know the date of his books and things, but I must have heard of him before I went up there."

Then, too, the friendly Dartmouth alumnus in discussing the College with him had given him "expectations of literary things" in Hanover, talking of Arthur Sherburne Hardy and the famous "Clothespin" Richardson, members of the faculty with reputations in the world of literature, Professor Hardy as a writer and Charles Francis Richardson as teacher, literary historian, and critic.

"There wasn't much of that, except that he could see the kind I was, sort of. I hadn't set any heart on being a literary person, but I was interested, you could see, in writing...."

Indeed, he had already had a few poems published in the school periodical, the Bulletin. "I wrote the first one the second year in the high school. And then I had one in the third year - one or two - and one probably or two in the last year, and one for the commencement, and that's all. I hadn't had any fury of writing, you know. Nothing like that."

A Dartmouth scholarship was, at any rate, arranged for, and Robert Frost, about to become a member of the incoming Class of 1896, "set off for up there with little money to spend and little need of it."

He still remembers with amusement one incident connected with his departure for Hanover. Having two or three hours to wait at Manchester, where he was to take the northbound train, he "went over to the library and got out a book by Hardy that I thought was this Arthur Sherburne Hardy." He knew Professor Hardy had written a novel or two (notably The Wind of Destiny and But Yet aWoman), and, of course, the talk of his literary accomplishments had placed the professor prominently in his mind. But, he smiles in reporting, "I guess I hadn't noticed first names enough." The book he chose was, he thinks, either Two on aTower or A Pair of Blue Eyes, early works of Thomas Hardy. "And maybe I got both of them out," he said with a grin. "And I read at them a little - thought I was going to see the man that wrote them up at Dartmouth."

His train ride northward ended at Norwich, just across the river from Hanover, and he can still visualize "the looks of the station and the wagon that went up," ascending the long, steep hill that leads to the College plain, and carrying him to the beginnings of his brief but memorable collegiate career.

"They gave me a room in the top story of Wentworth Hall on the side toward Dartmouth Hall. . . the back corner room, toward Dartmouth," Mr. Frost related.

"The room was a fair-sized room. I had to furnish it with a few things..., all secondhand. And then I had a little bedroom with a cot in it. As I remember that was a homemade cot - boards, as I remember it."

"I don't know what I did the first night. I couldn't have had this secondhand furniture the first night. Where," he puzzled, "do you think I lived? I don't know, somewhere; somebody took me in. No, I don't think so; I think I went right to that room, some way. That's my memory of it."

"Well," he continued, referring to his Wentworth quarters, "the first night I was in there, somebody opened my door and threw something in and upset my lantern; and then I was in the dark for awhile. And then I heard strange noises: not hammering at all, but it turned out that somebody had driven screws into the door so you couldn't open it. And there I was.. ..

"I thought this was all fun. It didn't worry me any. I thought that was what you came to college for," he chuckled. "The door was all abused with having been broken open and everything.... You could see this had been going on plenty. Nobody had any real privacy.

"I don't know how I straightened that out that night. I remember ... some professor came up the stairs, the top stairs. There must have been a lot of noise going on. They must have been making a big row there. I don't remember that too well, but I heard him say, 'Boys, boys, be easy on them.' "

Afterward he was told that it was "Tute" Worthen, then the College's Associate Professor of Mathematics, who had come to quiet the sophomores.

But how did he finally succeed in gaining his freedom from the cell they had created for him?

"Well, I don't know who got me 0ut.... I pounded on the door, but I don't remember anybody's coming." Apparently, however, he was eventually able to force it open himself from within.

THEN, at the very beginning, he made friends with another freshman there in Wentworth Hall, Preston Shirley of Andover, New Hampshire, and the two became fast friends.

"We held the fort together sometimes," he remembers of that period when night after night marauding sophomores laid siege to the stronghold they garrisoned in Shirley's room. "We decided there was more room down in his place: bigger I guess it must have been. He had a bigger bedroom or something.

"What brought that out was his mother sending him a box of fruit. His door opened inwards; and he couldn't eat the fruit, he knew they'd take it all away from us, unless we barricaded. So I came down there, and we took the closet door off the coal closet. (Each room had a big coal closet. We had to bring in our own coal, and some of us were forced to bring in other people's coal. I didn't get subjugated to doing that, but some did.) We tore off that door and took a slat off of his bed and nailed the slat into the floor and then braced the closet door against the outside door. And nobody could come in there, you see. That was very strong. We really fortified.

"But, of course," Mr. Frost added, "only one could go to class at a time, and we had to cut classes alternately.

"We ate the fruit, and I can't remember all the ins and outs of it. Late at night I must have gone up to my own room to sleep. I don't think I slept down there."

Preston Shirley's brother, Barron, had been graduated from the College the preceding summer. As Mr. Frost characterized him, "... he was a big, strong fellow - was powerful in the rushes, I heard - and quite a hazer, a leader in the hazing. Preston was a delicate boy, asthmatic and slightly deformed, but very full of Dartmouth traditions that you'd rather die than not live up to - wanted to be like his brother.

"His brother must have been rather a terror in it all. Preston hadn't the strength to be that, but he was always in the rows, around the edges or somewhere in them."

He "was really a very precocious person ..., very intellectual, and very sort of ironical and a little cynical even at that age.... What uncouthness he had, he had on purpose. He liked to be a little awful, you know: ... two-fisted Dartmouth man. He wasn't really that at all.. .. He wasn't big enough or tough enough."

"Didn't you and Shirley," I asked, having heard him allude to the incident before, "own something in common during this period?"

"Oh, a tub," he laughed. "Yeah, we quarreled about a tub. He said I used it too much: I had it in my room too much. Just a wooden washtub; that was our bathtub. That was the only kind of thing around."

But their falling out over the tub, was later made up over kerosene:

"One night... I met him coming across the campus from the stores... I think he had an empty kerosene can. He'd been out to get some kerosene, and he didn't get any. And so we made friends right then and there, because he needed some kerosene and I lent him some or gave him some.

"They used to say up there," he recalled humorously, "life was so humble that in our accounts home we could swell them easily by just putting 'kerosene,' 'kerosene,' 'kerosene' in. Ten cents made a lot of difference - 'twenty cents worth of kerosene,' you know."

MR. FROST went on to talk about the interclass rivalry that existed dur- ing those hectic early days of the fall term.

"I guess it was alternate classes," he said. "The seniors took sides with the sophomores, the juniors took sides with the freshmen —in sympathy just. And when we had a riot or fight they stood by sort of like our seconds to see us fight and see that there was nothing dastardly done.

"And then we began to have riots once a night, rushes. There were football rushes [in] which we used old-fashioned footballs - rubber, just those that children played with, no insides part to them, very round. Someone would kick those in between the two classes, and we'd fight for them and deflate them with nails. Everybody had a nail with him to deflate the darn thing. And we'd fight and fight.

"In the crowd you'd be saying, 'Let go, it's me.. ..' 'Let go, I got it.' You couldn't trust anybody.... Finally, somebody'd get it into his clothes, deflated. And then they'd realize it wasn't there, and the crowd would open up. Then anybody that was suspected of having it in his clothes would have his clothes pretty near torn off of him. They'd leap right on him. But to get away with the hidden ball was the next thing, to get home; and then the next day we'd wear pieces of it, the class that got it."

As he remembers it, the duration of the football rushes "must have been an hour or two of fighting" and that "there must have been three or four of those. My memory would be three."

There was, also, a "cane rush"; but one of the frays that he recalled especially was a "banner rush," which was another of the traditional contests of the day:

"We played a game of baseball between the freshmen and the sophomores once a year. That was fall, you see, not baseball season; but there was a big occasion. We were all out there on the baseball field. The sophomores had a banner - this was this formality - and we were supposed to attack the banner."

The group of freshmen of which he was a part "gathered around the sidelines of the ball game, and then we ran in and attacked the fellow carrying the banner... A vigorous scuffle ensued as the two classes fought it out for possession of the '95 pennant. "I don't remember just what I did," Mr. Frost declared, "but I think I had my hands on that banner, the cloth, when we tipped it over. We ran to the fence - the same fence was there - and there was a fellow named Chase, a sprinter in our class, a fast boy: he was there to take that and run. The last I saw of that he went off running. . . .

"We had that banner and cut it into pieces and wore that the next day."

Going on, he said, "Another rush we had, probably the most violent that I remember, was the 'salting' of the freshmen by the sophomores in the old Dartmouth chapel.... I have a picture of when the rush began: the President of the College [Prof. John King Lord was then acting as President] had been presiding over rhetoricals. (There'd been two or three seniors had spoken to us.)

"The President very hastily got to his hat and coat to get out of what he knew was coming. He didn't wait for it. He almost fled.

"There must have been a balcony that the seniors and juniors went up into to watch the fight.

"And then the sophomores from the short pews on one side came across on f00t..., climbed right across all those long pews to us in the short pews on the other side. And they all had a five or ten pound bag of rock salt.... They came filling the air with that like arrows at Agincourt.

"I didn't know this was coming; I didn't know the traditions. Shirley must have known all this; everything was regular every year. But I joined in the fight, and pretty soon we were using the cushions the old, dusty cushions - throwing those around. And some were using the old footstools - wooden footstools. And some were fighting on the barrier, some of the big fellows...; and on that barrier you could see fellows with their clothes half off, fighting. That's my memory of it.

"And when the dust got so I couldn't stand it any more, I got out. The dust was smothering. And Shirley got out - he got smothered 0ut.... I wasn't among the big brutes anyway, and he was far from it."

IN a different vein, Mr. Frost called to mind that it was while in Hanover, "I bought my first copy of Palgrave's GoldenTreasury, I think" - a book that was to mean a great deal to him over the years. "I bought that at the book store there." It was an edition in paper covers, and, he revealed, "I've got that still... somewhere; I don't know just where."

"We'll go on," he suggested, "and talk about the literary part of it. It couldn't have been long after that that I read Hovey's poem on the death of T. W. Parsons in the old library that's now the museum. I always hope they won't tear that down, because under that arch I went into my idea of publishing something."

It was in Wilson Hall that fall of '92 that the young freshman discovered on the display racks of the library a copy of the November 17th issue of The Independent, bearing on its first page Richard Hovey's poem "Seaward." As he described the experience, .. here was a magazine that I had never heard of, but it had a whole front page of poetry - all the page, three columns.... And then over on the next page some, I think. And then I leafed over, and there was an editorial on the poem.

"That made a big impression on me. I didn't think that minute that I'll send something there, but that was where it grew on me I'd send a poem there sometime. I don't know whether it came until I'd written the poem. Really, I can't remember that, but when I had the poem that I thought was a poem, I sent it there."

"I only remember," he said, referring to Hovey's poem, "one line of it, one new way of taking the Trinity: 'Trine within trine, inextricably One.' "

But he could still distinctly recall the appearance of that number of the magazine, there in the old library building.

"It was a big sheet. You know what it looks like. It was spread out like a newspaper on one of those open things. And I saw that poem there. As if I could see it today. That's why I must have had, more than you'd know, more interest in such a thing: What is that meaning? What does a big serious poem mean? And then I turned over, found talk about [it] in an editorial. So it meant that I was beginning to think of being a writer, I suppose. I can't remember that. I didn't know whether that was a thing to be or one ought to be or whether I wanted to be or what. I wouldn't know anything about that. I don't know what I thought I wanted to be. I don't know as I thought of anything. I was a good deal lost without minding being lost, you see...."

"That arch there, I always think," Mr. Frost reflected, "that that's sort of a beginning for me of something that was going to happen that year....

"Somebody talks about rededication and dedication, and nobody really dedicates himself till long afterward. He doesn't dedicate himself, he gets dedicated. He finds himself deep in something and long before he's aware of committing himself. And he's never aware of his taking his life in his hands to go forward to do something or do or die, you know, unless it's to battle or something.

"I didn't think anything like that. I just had it coming on me. I can't tell how it came, this wish to have something: write things and get them printed."

(It was in 1894 that Mr. Frost's poem "My Butterfly" appeared in The Independent, his first to be included in a publication of national circulation. It was written the spring after he left college and published the following year. He remembers that the editors "made quite a fuss over it," adding musingly, "sort of a premature fuss." And they were cross with him for having left Dartmouth. "They blamed me for that and reminded me of Milton, who was a very learned man.")

HE smiled as he turned to the subject of the "literary society" that he joined. It was the Dartmouth chapter of Theta Delta Chi, and one of the more wealthy brothers was so anxious to have him pledged that he went so far as to pay his entrance fee. "You see," Mr. Frost explained, "I didn't have any money."

He recalls, too, that he made the "opening speech" at the fraternity. "And I wonder," he pondered, "where that went, whether I wrote it out. Probably in those days I would write out something."

"They were very good to me, those fellows were. They'd been told by this man from Lawrence ... that I was literary I guess, though I didn't know that myself in any definite way. I wasn't thinking of it that way, but he thought I was....

"They didn't bother me except once that I've joked about. I've told about how they came to me, some of them, to know what I was walking in the woods for. And I told them that I was gnawing bark!"

"It sounds like American interference with freedom, you know, and independence. Nothing to that. They didn't want freshmen to be too fresh, doing things that others weren't doing."

He was at that time, as he has been throughout life, a great walker, but then, as now, he preferred to walk alone. He and Shirley might spend hours together talking, but they never walked with one another: the one caring nothing for this form of recreation, while the other disliked to talk as he walked.

"I walked all around there many miles. There used to be one, a seven-mile walkaround. ... I did that quite a lot.

"I didn't have very good health. I was strong in playing games and rushing and all that, but I don't know what was the matter. I think I was dispeptic and not sleeping well and all that. I had some special arrangement at the dining room not to have supper but just to have a couple of biscuits to take home in the evening. I didn't eat much at night.... I wasn't seeing any doctors or anything, [but] I hadn't been very well all my young days."

ALL the studies of that first term were prescribed, as was the case througout the freshman year. Beginning the classical course, he took Greek, reading Plato with Prof. George Lord ("That was very nice. I always seemed to like that kind of thing."), algebra with "Tute" Worthen ("He was a great favorite, and somebody that had an interest in the boys."), and Latin. The Latin course, concerned with Livy and Latin composition, was, unfortunately, something of a failure. The young tutor didn't have good discipline and the students treated him rudely:

"If he'd say, 'Take this for tomorrow,' and tomorrow was Monday instead of this week ..., they'd think that was time to 'wood up,' you know, and stomp the dust out of the floor. They'd do it over any little excuse they could make in that class. Some places they wouldn't do that at all; they wouldn't have thought of doing any such thing. . . .

"The Livy was no success that way. There was something disorderly about the class, I don't know why. The others were all right. There was no funny business with Worthen; and none with George Lord."

"I saw Richardson only once. He spoke to us," Mr. Frost quipped, "to arouse literature in us. And I remember his making a lot of two lines of Shelley about poetry being 'where music and moonlight and feeling are one.' "

He did not get to know any of the members of the faculty during his time in College. "I never spoke to any of them, really. At that age I never got acquainted with teachers 1 had people that I might have liked to speak to, but it wouldn't occur to me to do it, you know. I didn't know that was done."

And did he see anything of Prof. Arthur Sherburne Hardy?

"Not a once. He had a delicate wife, and he was much aloof; there was no chance, you see. He wasn't the kind of person. ... And then I heard his subject was quaternions, way in advanced mathematics where I wouldn't be for quite awhile."

Attendance at college prayers each week-day morning in Rollins Chapel was required: "I remember how I always just barely got into chapel in time. I claimed I could get in after the bells started ringing in the Dartmouth Hall - the big bells were up there."

Being a monitor for his class he took attendance, and, as he recalled puckishly, "I had chances of corruption in that. They were not for any gain, particularly; but they'd say, 'See me in chapel, will you, today? I don't want to go.' Not many."

He commented, too, on how the chapel periods "became very famous after I was gone. I began to hear of the fine speeches that Mr. Tucker made there."

He was, in fact, to have something more than a casual interest in the career of William Jewett Tucker, who during this same academic year 1892-93 was elected to the presidency of the College:

"I've told you that my mother taught high school in Columbus with him?" he asked. "She knew him slightly from those days and while he was in Andover and while those troubles were going on — not much, but a little from the old days. She taught seven years in the Columbus High School. I don't know how long he taught there.... We didn't have anything to do with each other especially, but she saw him once in awhile — somebody she admired. And then I heard of how much he did for Dartmouth right away, how the place came to life. It was a very low ebb. . . ."

Mr. Frost was, he tells, writing even during those days of harum-scarum, collegiate activity. Of the poems later to appear in his first regularly published book, A Boy's Will, it is possible that "Now Close the Window" can be traced back to a Dartmouth origin:

"I think that I had that on my mind unwritten for a long time — long time. And I do that sometimes — little short things. And I think I very likely made that up there."

Although he is understandably "very indefinite about some of the poems" and their associations, he is sure that part of another one had Dartmouth beginnings:

"I've often said that somewhere about that time I wrote some kind of a thing like 'Once by the Pacific,' mostly thrown away; but one or two lines survived out of that - clear back there: lines like 'The clouds were low and hairy in the skies,/ Like locks thrown forward in the gleam of eyes.' "

"Once by the Pacific" is, however, "an entirely different poem except for a couple of remembered lines. (I do that sometimes: I steal a couplet out of something that I throw away.) And I managed to, do it, I always fancy, so you wouldn't know there was any joint in it, you know; it comes in so natural...."

Another that seems to date back to his Dartmouth period is, Mr. Frost believes, "one of the first North of Boston things," now preserved at the Huntington Library in California. "It's an attempt to do 'The Black Cottage' in rhymed verse. I gave it up, and then [later] suddenly wrote it "

"That's the way you suffer most, is when you can't carry them out. When you carry - when they go smooth and you get an end, come right through, carry through - why there's no pain about that."

Of this early work he disclosed, "I was in a state then when I didn't always finish things. And one of the things I gained by being a newspaperman was that I had to finish everything. I've often said that, that up to that point I was like these fellows I see around who think you just write some texture. You see, it doesn't have to be anything: you write a poetic texture and you don't get anywhere and you leave it.... I didn't think you had to make anything. Well, that little while on newspapers made me round everything out, you see. You have a deadline, and you had to come to something. And I think it was about that time that I got more definite about ending them."

ANOTHER Of the escapades of his freshman days came into Mr. Frost's mind. "I didn't tell you that once I took part in hazing a classmate. Did I ever tell you that?"

The freshman in question was "a boy preacher," appropriately nicknamed "Parson" by his fellows.

"We fooled around, all one evening," Mr. Frost began, "he and I and Hazen, in Hazen's apartment. We had a field clay. And we busted the pillows over each other till the place was all full of feathers, and we carried on a lot....

"The others in that hall shouted at us to shut up, you know. But we kept right on: long jumps and short jumps and fights and everything and tearing pillows to pieces. And finally somebody said I needed a haircut.

"I said to the minister, 'I'll tell you what I'll do, if you'll let me cut your hair, I'll let you cut mine.' So Hazen and I cut his hair. We made a picture on the back of his head, so the skull showed through. . . . Then," he related with a chuckle, "I did a dastardly thing; I said we'd have my hair cut another night not that night. I refused to have mine cut.

"And do you know what happened to him? He left College."

"It was quite a mess we made of his hair.... It was all sort of half, you know, full of boyish badness though - ought not to have done it. It was one of the things I ought to be ashamed of.

"And," he continued, telling of their experience of the next day, "we went to find him. He wasn't in his room. We found him at the barbershop, and the barber was trying to smooth his hair out - and get it cut down level with that. And he was sitting back laughing, kind of puzzled, giving it up. . . . You couldn't do it. The figure stayed there. I suppose he left College on that account.

"I think it was not nice, but there was so much roughness going on that I just thought that was some of it. I shouldn't have done that. I was a funny kid; I wonder what I was like. I suppose I thought it was funny to be a young minister -boy preacher.... I ought to have been fired for doing that."

Many years afterward he again met the one-time "boy preacher," who showed not the least resentment over that incident of their student days. He had become a prominent man, an officer of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals in one of the states.

"I thought," his former hazer recounts, "when he said he was the President of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty ... to freshmen, I thought he was going to say, or ministers or something. But it was just animals!"

And Mr. Frost remembers, too, his own departure from College:

"Shirley thought it was awful that I should leave, but I didn't seem to have any sense of what I was doing. I didn't seem to think it was serious at all. I had no notion of being too poor to go on and get learning. Nothing like that. I sort of lost my interest.

"I had a kind of an appetite for a school awhile. (I had avoided school when I was young.) I got it first with love of recess and the noon hour. I couldn't miss what was going on there. So I went to school, and the first thing I knew I was fascinated with arithmetic and geography and history. And they couldn't interest me in grammar, I wouldn't go near the classes. I watched them diagramming a little on the board, but I wouldn't let on that I was learning grammar. I don't know why.

"Then I liked high school. They got me there. I liked it three years, and I got interested in the A's I was getting on top of everything. Then I got sick of that. In the last half I was sick of having teachers pulling my leg. .. just by marks. You see," he laughed, "I began to rebel. But nobody knew that. The last month or two I made my first absences. Something was coming over me. I hadn't missed a day for three years and a half, and then something came over me; and I resented this strain of being talked about as leading the class with so many persons right up behind me and who was my runner-up and all that. ... It began to make me nervous, and as I say, I never had very good health in those days. Somebody might say I was nervous - delicate person.

"Up there at College I showed the same symptoms of not wanting to talk about marks. I'd had enough talk about marks. It got to be almost a disease to me.

"And when I went out I just went easily, felt relieved. And Shirley couldn't get it through his head for awhile, but we sat up and celebrated all night the night before I went away. And we celebrated on Turkish fig-paste (Bought a whole lot of that. It's awful stuff!), and sang and carried on and hollered out our windows. And the next day I went down with my little trunk ... down to Norwich station and decamped."

Just when it was he left Mr. Frost is not sure, although, he says, "I think I had got past Christmas."

"I remember, I think it was at Christmas, that my mother sent a friend of mine up to see how I was keeping house in my room; and the ashes extended from the stove clear into the middle of the room."

Mr. Frost returned to Methuen, the next town to Lawrence, where his mother was having difficulty with some big and unruly boys in her class in the grade school. And this was some part of the son's reason for leaving College. He went to the chairman of the school board and asked to take over her job.

But the succeeding events are the elements of another part of the story of Robert Frost's career.

The mantel clock in the Brewster Street living room showed the hour to be a little after three in the morning, and it was clearly time for us to end our long and rambling conversation that had centered upon Mr. Frost's undergraduate reminiscences.

"All right," he said, as we concluded to break off our talk of those early Dartmouth experiences, "let's quit."

Robert Frost Uniquely Holds Two Dartmouth Honorary Doctorates

Robert Frost as he appeared at the time he entered Dartmouth in the fall of 1892.

Wentworth Hall as it looked when Robert Frost occupied Room 23 in the southeast corner of the top floor. Conversion to a classroom building in 1912 altered some exterior features.

Preston Shirley '96 was the closest friend ofRobert Frost in College, and the two madecommon cause in their defenses against theonslaughts of belligerent sophomore forces.

A fragment of the '95 banner that was at thecenter of one of the spirited "rushes" Mr.Frost recalls. It is preserved in an old scrap-book now in the Dartmouth College Archives.

"... Under that arch I went into my idea ofpublishing something." Wilson Hall, now theCollege Museum, was Dartmouth's Libraryfor some forty years, from 1885 until 1928.

Beginning in 1916, soon after his return from England, Mr. Frost has come back frequently to read and lecture at the College. From 1942 to 1949 he was Ticknor Fellow in the Humanities, which brought him into close touch with student groups, as shown above.

As a self-styled "kind of Ledyard fugitive," Mr. Frost has long regarded John Ledyard, Dartmouth 1776, as "the patron saint of freshmen who run away," and he is fond of telling how he likes when in Hanover to make a pilgrimage to touch his monument, located near the. banks of the Connecticut.

1933 "...who needs no honors save as a sign of affection." At right, Mr. Frost sits on the Commencement platform waiting to receive from President Hopkins a Doctor of Letters degree, forty years after he had ended his brief period as a Dartmouth freshman.

1955 "... because ours is a love long learned." President Dickey in his citation declares, "Dartmouth dares doubt that one honorary Doctorate of Letters is enough and herewith. . . adds in witness o£ all left unsaid her honorary Doctorate of Laws."

HAVING NEARLY THIRTY honorary degrees from colleges and universities at home, Mr. Frost in 1957 flew to England, where A Boy's Will and North of Boston had first appeared over four decades before, to receive doctorates from both Oxford and Cambridge. The National University of Ireland also bestowed upon him its honorary D.Litt. In the picture opposite, Mr. Frost and Mr. Lathem, in Oxford's New Bodleian Library, discuss a contemporary account of Longfellow's degree from the University, awarded in 1869.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature"Spoiled Children" of Hanover: A Letter from Charles Doe, 1849

March 1959 By JOHN P. REID -

Feature

FeatureSCHOOLMARMS, GRAMMARIANS and ANARCHISTS

March 1959 By ROBERT S. BURGER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

March 1959 By THOMAS E. SHIRLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, RICHARD P. WHITE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1950

March 1959 By SCOTT C. OLIN, SIMON J. MORAND III -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

March 1959 By ROBERT L. MAY, EDWARD J. HANLON, BRUCE W. EAKEN -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

March 1959 By CHESTER T. BIXBY, CHARLES H. JONES, TRUMAN T. METZEL

EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

January 1954 -

Article

ArticleMr. President, LL.D.

October 1953 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51 -

Feature

FeatureTHE MOCK-DUEL MURDER

April 1956 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51 -

Feature

FeatureChronicler of Gettysburg

May 1958 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51 -

Feature

Feature"As I Remember..."

January 1960 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51 -

Feature

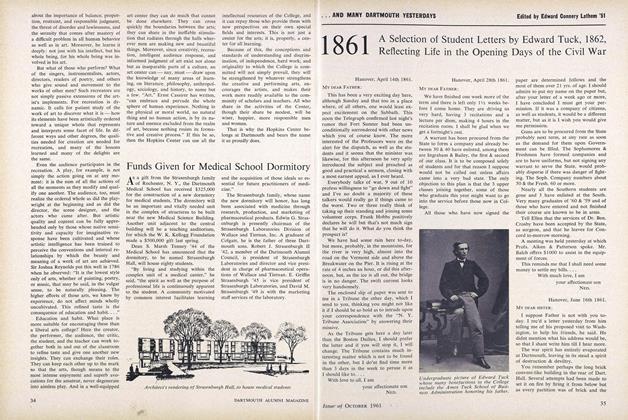

Feature... AND MANY DARTMOUTH YESTERDAYS

October 1961 By Edward Connery Lathem '51

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe State of Our Purposes ... and Vice Versa

March 1958 -

Feature

FeatureMay 17 Event to Salute Eleazar's Starting Point

MAY 1969 -

Feature

FeatureLate Afternoon Thoughts On the Twentieth Century

September 1986 By LEWIS THOMAS -

Feature

FeatureArt Imitates Life

MAY | JUNE 2017 By LISA FURLONG -

Feature

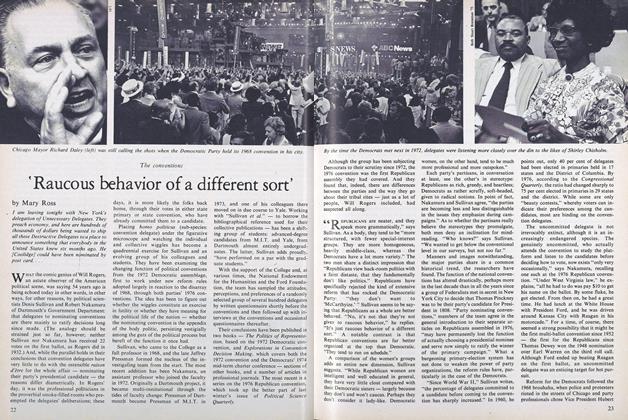

Feature'Raucous behavior of a different sort'

December 1978 By Mary Ross -

Feature

FeatureThe Mold

SEPTEMBER 1996 By Warren Cook '67