The Spirit of the Common Law: by Roscoe Pound, Carter Professor of Jurisprudence in Harvard University and Dean of the Harvard Law School. Dartmouth Alumni Lectureships on the Guernsey Center Moore Foundation, pp. xiv: 224. Boston: Marshall Jones Co.

As long ago as 1906, Dean Pound delivered before the American Bar Association what has been described as "an epoch-making address" on "The Causes of Popular Dissatisfaction with the Administration of Justice". Ever since, he has been energetically at work, studying, teaching and preaching the gospel of sound legal learning, high legal standards and constructive, scientific law reform.

As he himself puts it in his preface, it has been his creed that "the administration of justice may be improved by conscious intelligent action", and that "when the lawyer refuses to act intelligently, unintelligent application of the legislative steam-roller by the layman is the alternative."

These lectures may be described as the essence of that creed. They may be much better described in the author's own words as "the taking stock of the materials with which we must work"; an effort "to examine the body of legal tradition on which we rely, to ascertain the elements of which it is made up, to learn its spirit, and to perceive how it has come to be what it is, to the end that we may know how far we may make use of it in that stage of legal development upon which the world has now entered."

For Dean Pound believes that "in the United States, a revival of philosophical jurisprudence has definitely begun and conscious attempt to make the law conform to ideals is once more becoming the creed of jurisprudence."

In the course of his stock-taking, he analyzes the contributions, useful or harmful, which have been made to our common-law system by feudalism; by Puritanism; by the controversies with Tudor and Stuart; by the eighteenth-century doctrine of the natural rights of man, and by the nineteenth-century individualistic philosophy, as that was re-emphasized by the pioneer conditions of America before the Civil War.

This analysis is critically keen and discriminating; if the work stopped here, it would stand as a product of painstaking and ripe scholarship. But it does not stop here; its chief value, and indeed that which marks it off as an outstanding achievement, is its look forward, not its look back.

For it is the author's well-reasoned conclusion as the result of his inventory that the outstanding features of our Anglo-American common-law system, which are (1) the supremacy of law, (2) the doctrine of judicial precedents, and (3) the trial by jury, need not be abandoned in order to administer justice in an industrial, urban, polyglot modern society; on the contrary, that if they are used and worked over intelligently and cooperatively by lawyer, legislator, and judge, their amazing "tenacity and vitality" can be turned to good account in the reasonable socialization of the law which must be had, unless all respect for law is to be lost.

It was the well-authenticated rumor not long ago that certain influential gentlemen were so much disturbed about Dean Pound's "radical" views as to doubt the desirability of his continuing in his present post. Isn't it strange how hard it is for some people to recognize a true conservative when they see one!

It is a significant thing that a six-months period should have seen the publication of three such works as the Carnegie Foundation's "Training for the Public Profession of the Law", the "Cleveland Survey", and the book under review.

Nor would it be difficult to trace their logical connection with the violent but salutary purging which Boston is undergoing and which New York and other centers sadly need.

But this is supposed to be a book review, and not a dissertation on legal education or legal ethics.

Let it be concluded with the expression of the pious wish that this book might be read and digested by every law student, lawyer and judge in the land; and with the reviewer's judgment that these lectures represent the greatest contribution to American jurisprudence for at least a generation.

Dartmouth is fortunate in being the conduit through which they are conveyed to the public.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleCOLLEGE DISCIPLINE

March 1922 By EDWIN JULIUS BARTLETT '72 -

Article

ArticleAthletics in general and football in particular seem to be up for special

March 1922 -

Article

ArticleTHE COLLEGE GRANT

March 1922 By JOHN M. GILE '87 -

Article

ArticlePRESIDENT HOPKINS EXPOSES "FUNDAMENTALIST" MOVEMENT

March 1922 -

Article

ArticleTWELFTH WINTER CARNIVAL A HUGE SUCCESS

March 1922 -

Sports

SportsBASKETBALL

March 1922

JAMES P. RICHARDSON

-

Books

Books"The Law as a Vocation"

October 1919 By JAMES P. RICHARDSON -

Books

BooksTrade Associations

August 1921 By James P. Richardson -

Article

ArticleThe Need of Change

JUNE, 1928 By James P. Richardson -

Article

ArticleAnother National Appears

JUNE, 1928 By James P. Richardson -

Books

BooksEDWARD COKE, ORACLE OF THE LAW.

FEBRUARY 1930 By James P. Richardson -

Article

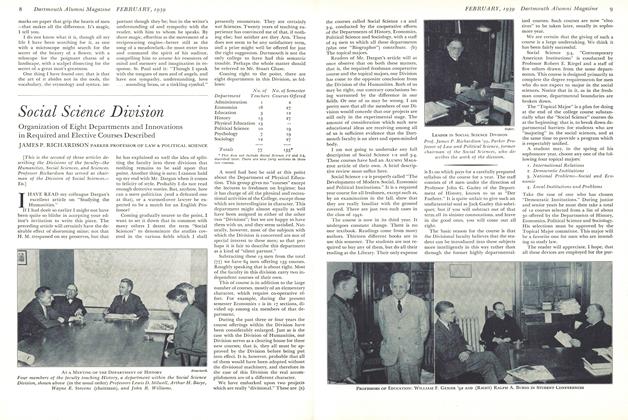

ArticleSocial Science Division

February 1939 By JAMES P. RICHARDSON

Article

-

Article

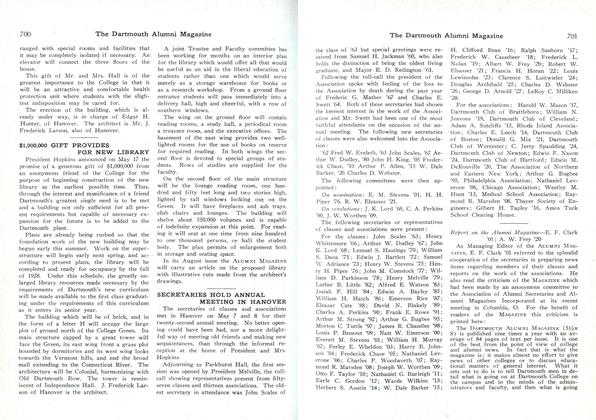

Article$1,000,000 GIFT PROVIDES FOR NEW LIBRARY

June, 1926 -

Article

ArticleTuck, Thayer Speed Work

January 1942 -

Article

ArticleGreat Issues Reprints

October 1953 -

Article

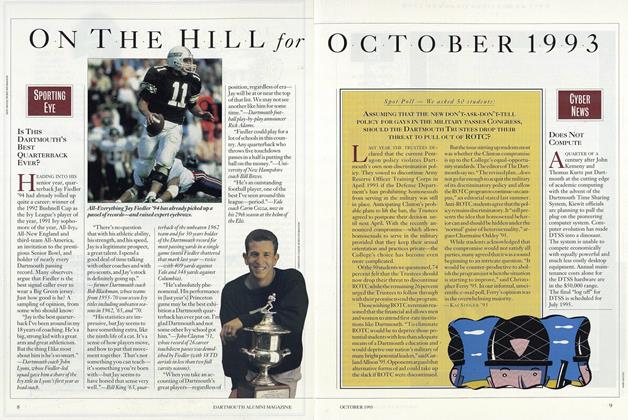

ArticleIs this Dartmouth's Best Quarterback Ever?

October 1993 -

Article

ArticleTHE NEW BARBARIANS

OCTOBER 1964 By ALLEN R. FOLEY '20 -

Article

ArticleTRAIN

December 1936 By ROBERT A. SELLMER '35