Your government holds that reeducationof the German people is an integral partof policies intended to help develop ademocratic form of government and torestore a stable and peaceful economy; itbelieves that there should be no forciblebreak in the cultural unity of Germany,but recognizes the spiritual values of theregional traditions of Germany and wishesto foster them; it is convinced that themanner and purposes of the reconstruction of the national German culture havea vital significance for the future of Germany.

You will encourage German initiativeand responsible participation in this workof cultural reconstruction, and you willexpedite the establishment of those international cultural relationships which willovercome the spiritual isolation imposedby National. Socialism on Germany andfurther the assimilation of the Germanpeople into the world community of nations. (Directive for U. S. Objectives andBasic Policy in Germany, issued July 15, 1947, Section 6, Cultural Objectives.)

IN the fall of 1948 I became a member of the staff recruited by the United States Office of Military Government for Germany to develop procedures and practices to implement this directive. In my work as Chief of the Cultural Affairs Branch, it early became apparent that we were without a training precedent for the development of a program of activities which would achieve within a reasonable space of time the objectives described by the directive. The widespread physical destruction of public schools, libraries, museums, theatres, churches and other cultural equipment of German society had forced the occupation authorities to devote the greater part of their time to the purely physical needs of reconstruction.

Improvement of the physical aspects of the cultural life of the nation had made considerable progress by the fall of 1948 but these were still vastly inadequate even to meet the needs of the children for normal education purposes; the rebuilding of libraries, museums, theatres and churches was still largely in the planning stage. Many public cultural activities were still licensed by the occupation authorities and rather strict controls were practiced in dealing with all cultural institutions and organizations, both public and private. Each of the four occupation countries had complete autonomy over all social and cultural affairs in its prescribed zone. The denazification courts established by the local German authorities under the supervision and direction of the occupation forces had largely fulfilled their functions but were still active. Currency reform had been effected and the general economy was beginning its vigorous activity which was to culminate in one of the strong and stable economies of western Europe.

The fighting war had been over for three years and the cold war, as exemplified by the Berlin blockade, was impressing itself on the minds of both the other occupation authorities and the German people. It was a sort of cultural interregnum both occupation-wise and German-wise. The general policy of the American occupation was already moving swiftly from the punitive phase to the corrective phase; the procedure, from command to persuasion, as embodied in the directive cited above. A fresh beginning of the implementation of our cultural directive was given us by new instructions from the United States commander-in-chief in his address at Berchtesgaden, September 1948, to his civilian staff interested in cultural affairs.

During most of the first year of my tour of duty, efforts were largely devoted to effecting changes in policy in reference to the major cultural activities of German society in the American zone of occupation, and recruiting a staff adequate to cope with our new responsibilities. One relatively small interest and activity was an attempt on our part to effect, if possible, some exchange among university students. German universities were overcrowded, understaffed, and had only a minimum of classrooms and books. Obviously it was impractical to attempt any true exchange, but it seemed highly desirable to send some German students to American universities. We developed a special project in our Cultural Affairs Branch and were able through budgetary manipulation to charter two planes which carried 123 German students to colleges and universities in the United States with which we had previously made appropri- ate arrangements. Such was the small be- ginning of an Exchange of Persons Pro- gram which was to be responsible, before I left Germany in 1952, for sending approximately 10,000 German citizens from all walks of life to the United States and other European countries.

At the end of the first year, the Department of State assumed the responsibility for the German "reorientation program" which had been by then developed rather extensively with strong emphasis on the social-political reorientation of the German people, not only in the American zone, but also in the British and French zones. The cold war was on in earnest and its tempo was being increased constantly, thus emphasizing the need for a new time schedule if our reorientation program was to become effective. Long-term planning had characterized our military government programs, especially in the cultural areas. Now it became necessary to combine our efforts in the field of public and cultural affairs with those political and economic. We could no longer think in terms of 25 years or ten years, or even five years, but were forced into a position of accomplishing what we could in whatever time might be permitted to us before, perchance, the Russians might suddenly convert a cold war into a shooting war.

While the German program was techni- cally an integral part of the world-wide Information and Education Programs of the State Department administratively, our basic objectives were and continued to be essentially different from those which obtained for the same type of program carried on with sovereign states. Even our budget was derived from the special ap- propriation ear-marked for occupation ex- penses. Traditionally and currently ex- changes of persons among nations has been, since our first governmental experi- ence in this field (Boxer/Chinese stu- dents), largely devoted to persons associ- ated with formal educational institutions; for example, students and professors of colleges and universities. In Germany, as in Austria and Japan, we were now engaged in the task of democratizing a society which only recently had, in the majority, not only accepted but had supported to the death, an antithetic national ideology. If a program of exchange of persons between Germany and the United States was to be used as a positive instrument in the creation of a sovereign democratic state in Germany, it was obvious that its effectiveness would be meager if we followed the single traditional pattern of academic exchange.

Lengthy discussions between cultural officers of the High Commissioner s Staff and representatives of the State Department from Washington proceeded rapidly during the early months following the control of the High Commission. Agreement was reached to accept and implement the basic cultural aims derived from the programs planned by the Office of Military Government and to apply these aims not only to a program of exchanges but also to information centers and other indigenous educational and cultural programs funded by counterpart Deutscher Marks derived from ECA. All these programs were the responsibility of the Office of Public Affairs and were supplementary to the customary mass media information activities, some of which were definitely planned for propaganda purposes. Shepard Stone, Dartmouth '29, was the director of all these activities under the United States High Commissioner.

BASICALLY we agreed that our cultural efforts should be entirely free from propaganda and based upon the spread of truth. Our major aims were five in number: (1) to increase respect for the dignity of human personality and human rights by encouraging humanitarian feeling, freedom of thought and expression, deference to personal convictions and minority opinion, and liberal social attitudes; (2) to develop representative and responsible self-government by arousing a sense of social responsibility for matters of public concern and encourage recognition that public officials are servants of the public; (3) to aid the German people in their own efforts to readjust, reorganize, and redirect their own social institutions; (4) to increase respect for cultural attainments of other nations and to assist the Germans in reviving and developing the true values of German culture; and (5) lastly, to aid the Germans to free the younger generation from nationalistic ideologies, to develop democratic attitudes and beliefs, and to translate them into everyday life.

An Exchange of Persons Program, to be effective in the implementation of these aims, involved giving attention to persons in the German society who were presently influential in all the diverse primary and secondary social groups which customarily are to be found in any western nation. In addition, it involved the need for the ad- vice and assistance of similar leaders from the United States and other democratic countries in their respective areas of social, political, and cultural activities. With this general pattern in mind we proceeded to develop a staff capable of administering a plan by which Germans in those categories, whom we designated "opinion moulders," could be selected and sent on study or observation visits to the United States or to other democratic countries. Concomitantly our State Department colleagues in Washington could select and send to Germany the Americans whom we called "specialists" to advise their German counterparts. The American missions in other European countries also assisted in selecting European "specialists" for a similar purpose.

A pattern eventually evolved which proved effective and in general followed these lines. Each "specialist," European or American, brought into Germany, was attached to a German institution or agency in his specialized field where he endeavored to promote interest and understanding in the democratizing of that institution or agency. When the "specialist" had completed his tour, generally ranging from three to six months, we would then select "opinion moulders" from the institution or agency concerned and send them for a study-visit to the United States or to some European country where this activity seemed to provide the quickest and best opportunities for the German's reeducation. On the return of the German "opinion moulder" we stood ready to assist his efforts in reforming the institution or agency by subsidizing the activity with which he was associated through a "grantin-aid" in local currency. While this plan did not always obtain, we perfected it in so far as it was humanly possible within the limitations of staff and budget, two items with which we were constantly concerned. In this manner the need for exchanges grew extensively, since this program became somewhat the core or center of many basic areas of the total cultural reorientation effort. The "opinion moulder" phase of the program constituted approximately one-half of the complete program for exchanges. We continued and expanded our student exchanges, added new categories for elementary and secondary school teachers, and developed a new area for teen-age youngsters who came to live on American farms and in village homes for a year.

By 1950 we had organized a wellplanned exchange program in 16 socialcultural areas: rural living (agriculture), community leadership, public education, information media (radio), information media (journalism), labor affairs, legal affairs, libraries and museums, political leadership, public affairs, public health and welfare, religious affairs, social services, students and teen-agers, women's affairs, and youth leadership. In each of these areas projects were developed, personnel and budget quotas established, and the total program approved by the Exchanges Staff approximately one year in advance of its actual implementation.

In order to screen out the undesirables and establish principles to provide guidance in securing the most effective people to send on study visits, we established a list of priority characteristics to aid in selection. First, we sought "persons in positions of public responsibility," i.e. government officials, political leaders, legislators, and the like; second, "persons not in status of public authority but in positions of public influence," i.e. teachers, labor leaders, editors and others directly concerned with public information; third, "persons concerned with the institution and development of new democratic institutions, movements, and projects," i.e. community councils, parent-teacher associations, school development, and the like; fourth, "persons leading or representing groups or professions of critical importance for democratic reconstruction and reform," i.e. women's groups, youth organizations, trade unions, farm cooperatives, etc.; and fifth, "young persons of promise who were preparing themselves for public service careers and positions of leadership and influence in their community."

BY the fall of 1951 our operation had been extended to include all of western Germany, completely ignoring the zonal boundaries between the American, French, and British areas. From this point on our personnel quotas were largely determined on the basis of population distribution within the regional or geographical areas which we had established to administer the program. These geographical areas were delineated in direct relationship to the official United States consular districts. Western Germany is divided into six consular districts plus an independent consular office in the western sector of Berlin.

These consular areas proved to be too extensive for efficiency in administering the program at the "grass-roots" and were in most cases divided fairly equally in terms of their population. Regional offices were therefore established in Hamburg, Bremen, Hannover, Dusseldorf, Coblenz, Frankfurt/Main, Stuttgart, Freiburg, Munich, Nuremberg and Berlin.

The central exchange offices had moved with the headquarters staff of the Office of Military Government and later that of the High Commissioner. Thus the original site was in Berlin, then Nuremberg, BadNauheim, Frankfurt/Main, and finally Bad Godesburg near Bonn. The overall program planning and administrative coordination were centered in headquarters staff but more and more we were giving greater autonomy to the regional offices.

We classified all the projects into two general areas in relation to selection of the Germans: competitive and non-competitive. Those areas involving mass movements like students, teen-agers, teachers, etc. were all competitive categories. In those areas the projects would be publicized widely by radio and press through the regional offices. Appropriate application forms were distributed, deadlines for their presentation established, and candidates were informed to appear before committees in the several regions and make formal application for participation.

Each exchange area had two types of committees, a central regional committee and a local panel. The regional committee was composed of influential German citizens with the American exchange officer as chairman, and the local panels were organized similarly. As soon as possible these committees were staffed by German returnees from the program. The responsibility of the local panels was to make the first screening and to present to the regional committee twice as many names as called for in the project. When the reports were completed by the local panels, the regional committee had the responsibility of making the final recommendations from the list thus presented. Simultaneously, on an agreed date, reports of all the regional committees were forwarded to headquarters where a panel representing the interests of the High Commission and the German Federal Agencies, if any were involved, made the final list, together with alternates, for recommendation to the State Department in Washington. The extent of the problem of selection may well be illustrated by the fact that in the fall of 1951 over 13,000 applications from "teen agers" were made against an overall quota for only 400 possible placements.

The non-competitive categories included all the so-called "leaders" or "opinion moulders." Here the procedure was quite different. While the final recommendation for selection was the responsibility of the regional exchange officer, he was expected to utilize the services of his colleagues as well as influential German citizens in requesting nominations for participation in these projects. Over the years our staff had been slowly accumulating the names of prominent Germans and in 1952 we definitely pointed our efforts toward creating a "Who's Who" of potentially good candidates.

One of the basic problems constantly encountered in selecting the leaders was security clearances for a visa. This became an almost insurmountable problem with the implementation of the so-called McCarran Act (the Internal Security Act, 1950) and it virtually stopped our program for several months. It proved to be increasingly difficult to find leading Geiman citizens who had not in some way been associated with Nazi organizations under Hitler's government. Even though German leaders may have been exonerated by the denazification courts, very often the United States consular offices were even then unable to provide a visa due to some legal or political technicality. Much less trouble was encountered when we were dealing with the youth and dent groups; in general visas could be obtained for them unless they indicated voluntary membership in some Nazi Deutsche Jugend organization. Other problems of selection in the leader program stemmed from the inability of many outstanding Germans to speak English and from the impracticability of leaving their positions for any extended period of time. These problems were ameliorated to some degree by furnishing interpreters during the German's tour in the United States and by adapting the length of the visit to individual needs.

THE evaluation and follow-up unit which was an integral part of our headquarters staff is one aspect of the program which merits comment. The chief of this unit was one of our Dartmouth graduates, Charles Dean Chamberlin '26. This unit provided constant reporting on the effectiveness of the program through interviews. public opinion polls, and various anecdotal information obtained from the Germans who had returned to Germany under our program. They furnished us with material to support our budget claims before Congress and acted, in general, as liaison effecting our public relations in the German press. Chamberlin has continued in this service and is presently in Germany.

In terms of dollar appropriations the cost of the program moved from approximately 1100,000 in 1948 to over $6,000,000 in 1951. The 1952 budget was somewhat under this figure. This meant, in terms of German exchangees during the four-year period, some 6500 Germans coming to the United States for varying periods of time, and about 3500 going to European countries. The majority of our European exchangees went to England, Switzerland, Sweden, France and Finland.

After extended communications between HICOG, the State Department, and the German Foreign Office for Cultural Affairs, I was able to negotiate successfully the Executive Agreement necessary for the establishment of the so-called Fulbright Exchange Program. This agreement was signed for the United States by John J. McCloy, the High Commissioner, and for the Federal Republic of West Germany, by Conrad Adenauer, the German Chancellor, on July 18, 1952. The agreement signed called for the expenditure of the equivalent of five million dollars, in local currency, to be spread over a period of five years, not to exceed the equivalent of one million dollars a year. This pro- gram is now in operation and is being im- plemented by the present Exchanges Staff in Bad-Godesberg, Germany, in coopera- tion with the federal Kultus Ministerium in Bonn. This executive agreement may be extended for a total of twenty years provided, at the close of five years, local currency is available and the program is mutually agreeable.

The so called Fulbright Act is actually Section 32 (b) of the United States Surplus Property Act of 1944 as amended by Public Law 584 of the 79th Congress. It provides that the Secretary of State of the U. S. may enter into an agreement with any foreign government for the use of currencies or credits for currencies of such foreign governments acquired as a result of surplus property disposals for certain educational activities. The interpretation of the Act permits financing exchange of persons between the United States and Germany (or any other country with similar agreements) in the categories of college and university students and professors, research scholars, and secondary school teachers.

THE foregoing description of the organization, procedures, and scope of the German Exchanges Program may be of some interest, but sheds no light on the measure of the program's value in the democratization of Germany which depends largely on whether those Germans have acquired the pattern of democratic living themselves, and further, have transmitted any of this spirit to the rest of the population. The ultimate effect of the program on German thought and action cannot, of course, be immediately computed any more than we can make any apriori measure of the influence of new ideas, techniques, or philosophies on other people. Nor is it possible to measure directly the specific and immediate effect of such a program. One can, however, evaluate some of the immediate aspects of the program through the newer techniques of the social scientist, through an analysis of reports written by returnees, and other anecdotal writings. In many cases the returning Germans engaged in writing, lecturing, and group discussions to communicate their experiences and knowledge to professional colleagues and to the public. They frequently organized into groups interested in measures which will ultimately bring about major changes in the German social system. It would be possible to cite scores of examples of this type of effectiveness.

The most comprehensive and the latest analysis of the effect of the Exchanges Program was published during the last week of August 1952, only four days before I sailed from Bremerhaven on my way back to Hanover. This report was made by the Reactions Analysis Staff of the Office of the High Commissioner for Germany. It is entitled "West German Receptivity and Reactions to the Exchange of Persons Program." The field work on the survey was made in January and February, 1952, after some 4,000 German nationals had returned from visits of varying duration to the United States. The 1200 scientifically controlled probability samples were selected from all three zones of Western Germany plus the western sector of Berlin. All cases were adults 18 years and older, and none had participated in the program.

The survey was strictly a German public opinion poll. Briefly, this extensive report tried to get an answer from the German people to three questions: first, the general receptivity to the Exchanges Program; second, the awareness and general evaluation of the program; and third, detailed evaluation of the program. Some highlights under these three divisions are at least illuminating.

In general, the principle of the international exchange of ideas is widely accepted but it was interesting to note that while seven in ten felt that the Germans can profit from such an exchange, nine in ten stated that other nations can learn from Germany. In the crucial political area, Germans show considerable reserve. Only about one-half of those queried expressed the opinion that other nations could teach the Germans anything about political processes and government. As far as learning from the United States was concerned, there was a high degree of receptivity but it varied widely with the type and kind of activity. A clear majority thinks there is something to be learned from the United States in the industrial, technical, and cultural fields, but in certain key social areas receptivity is relatively low. Only about one-third of the West Germans think there is anything to be gained by Germans studying American experience in political and governmental processes, education, and labor relations. Only very few fear that Germans will be adversely influenced by a sojourn in the United States, and the largest percentage of these fears was based on the notion that the German would want to emigrate and be dissatisfied with life at home. Reports by Germanvisitors to the United States were considered by other Germans to be more reliable than any other avenue of information about America.

The second division on the awareness and general evaluation of the program indicates that four out of ten of the general population claim awareness, but the better educated and those in the higher income, prestige occupations are much more likely than the rest of the population to know about the program. It is quite important to know that only a small minority attribute negative values for American interest in such a program. Three-fourths of those who were aware of the program said it was "of great value to Germany" and their major criticism suggested that it should be expanded in various ways. The comments of the fraction who disparaged the value of the program were not necessarily hostile to the United States, but rather indicated a kind of ethnocentric pride in the German attributes and achievements.

The third part of the survey confined itself to those Germans who were personally familiar with the exchangees' experiences; thereby some detailed evaluation of the program was indicated. Two out of five interviewed said that "new ideas" have come to them from what they knew of some returnee's experiences. These "new ideas" are largely favorable from the West's point of view. Eight out of ten were quite affirmative in their impression that the returnees' experiences could be useful in Germany. Those 4,000 returned exchangees have probably talked to one million persons about the Exchange Program. There appears to be considerable direct personal transmission by exchangees which suggests strongly that their individual experiences go far beyond themselves. Most of the Germans who have talked with exchangees indicate that they have been influenced in a "good" way and support their reaction by specifying in what way the influence had been favorable.

I am optimistic enough to believe that, given time and continued United States effort on a relatively extensive basis, my concept of an exchangee as a "democratic catalyst" in the German social order will eventually prove to be a significant factor in the ultimate democratization of the people living in this important strategic area of the Western World.

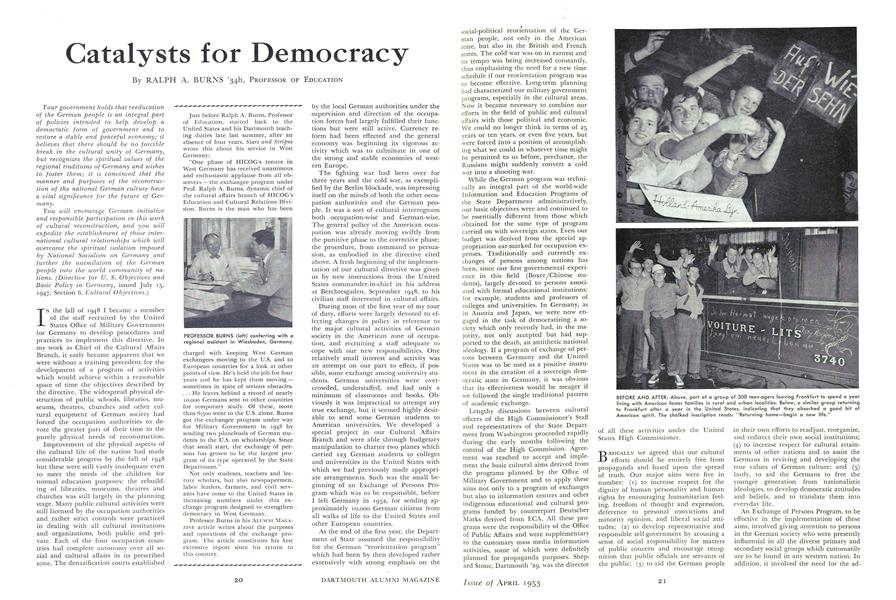

Just before Ralph A. Burns, Professor of Education, started back to the United States and his Dartmouth teaching duties late last summer, after an absence of four years, Stars and Stripes wrote this about his service in West Germany:

"One phase of HICOG's tenure in West Germany has received unanimous and enthusiastic applause from all observers the exchangee program under Prof. Ralph A. Burns, dynamic chief of the cultural affairs branch of HICOG's Education and Cultural Relations Division. Burns is the man who has been

charged with keeping West German exchangees moving to the U.S. and to European countries for a look at other points of view. He's held the job for four years and he has kept them moving sometimes in spite of serious obstacles. ... He leaves behind a record of nearly 10,000 Germans sent to other countries for temporary study. Of these, more than 6,500 went to the U.S. alone. Burns got the exchangee program under way for Military Government in 1948 by sending two planeloads of German students to the U.S. on scholarships. Since that small start, the exchange of persons has grown to be the largest program of its type operated by the State Department."

Not only students, teachers and lecture scholars, but also newspapermen, labor leaders, farmers, and civil servants have come to the United States in increasing numbers under this exchange program designed to strengthen democracy in West Germany.

Professor Burns in his ALUMNI MAGAZINE article writes about the purposes and operations of the exchange program. The article constitutes his first extensive report since his return to this country.

PROFESSOR BURNS (left) conferring with a regional assistant in Wiesbaden, Germany.

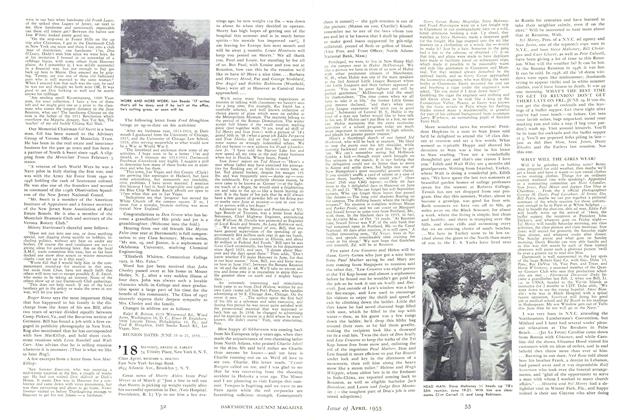

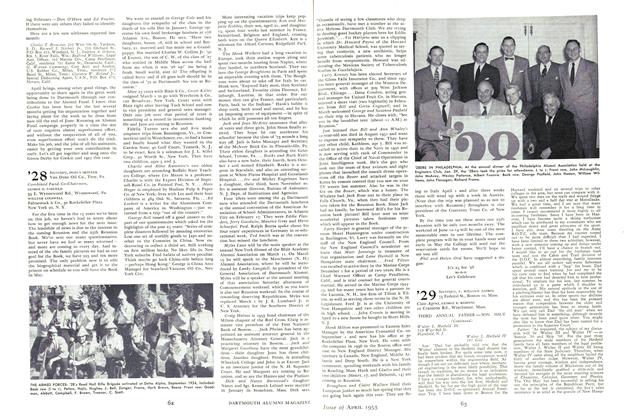

BEFORE AND AFTER: Above, part of a group of 300 teen-agers leaving Frankfurt to spend a year living with American foster families in rural and urban localities. Below, a similar group returning to Frankfurt after a year in the United States, indicating that they absorbed a good bit of American spirit. The chalked inscription reads: "Returning home—begin a new life."

BEFORE AND AFTER: Above, part of a group of 300 teen-agers leaving Frankfurt to spend a year living with American foster families in rural and urban localities. Below, a similar group returning to Frankfurt after a year in the United States, indicating that they absorbed a good bit of American spirit. The chalked inscription reads: "Returning home—begin a new life."

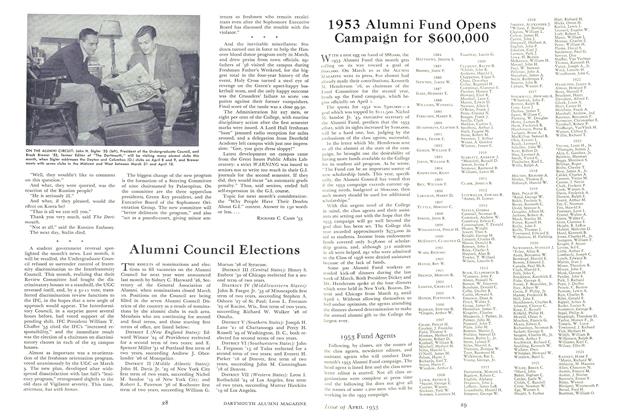

LEARNING ABOUT THE UNITED STATES: Exchangees from Germany shown (left) with the Mayor of Traverse City, Mich., after a City Commission meeting, and {right) at a "grass roots" picnic gathering with members of the Mancelona, Mich., Rotary Club. The force of public opinion was studied in both instances.

PROFESSOR OF EDUCATION

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

April 1953 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Article

Article1953 Alumni Fund Opens Campaign for $600,000

April 1953 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

April 1953 By KARL W. KOENIGER, HOWARD A. STOCKWELL -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

April 1953 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, GEORGE B. REDDING -

Article

ArticleTHE COLLEGE

April 1953 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1928

April 1953 By OSMUN SKINNER, GEORGE H. PASFIELD, WILLIAM COGSWELL

Article

-

Article

ArticlePhi Beta Kappa

March 1944 -

Article

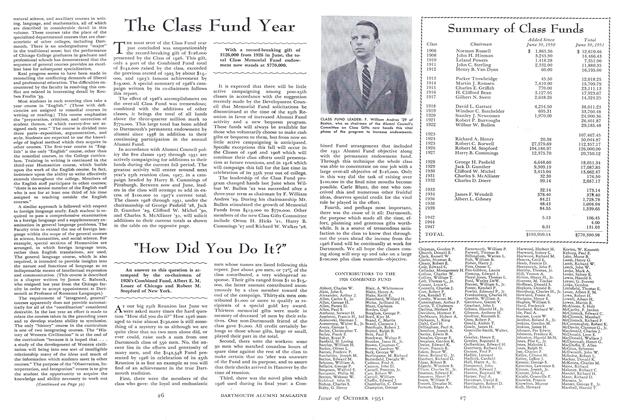

ArticleThe Class Fund Year

October 1951 -

Article

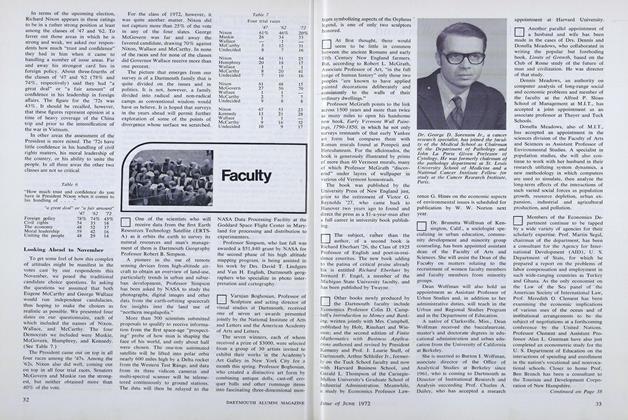

ArticleFaculty

JUNE 1972 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Article

ArticleWorld Champ Puzzlers

NOVEMBER 1992 By Tig Tillinghast ’93 -

Article

ArticleAbout 25 Years Ago

January 1938 By Warde Wilkins'13 -

Article

ArticleRichard Hovey

November 1957 By WILLIAM PLUMER FOWLER '21