I attended a rock concert in Hanover the other night. It was not a very memorable concert, but two lines stand out in my mind. "Endless frustration brings confusion.

There's too much confusion — get me out of here." The Dartmouth campus is quiet — very quiet. Some say it's too quiet. As the song alleges, one can almost hear that crunch of feet on the newly fallen snow. There is no question that everything, everyone for that matter, is more sedate. The jackpot questions are: why is it happening and why now?

There is, of course, very little concrete evidence to demonstrate that activism is dying out. On a national scale, college demonstrations are down this year as compared with a corresponding period last year. The Nixon Administration prides itself on the contention that students are gradually accepting the White House viewpoint on the war in Southeast Asia. It is, however, naive to view the decrease in the number of demonstrations as indicative of a major shift in political attitudes. There is more to the "new atmosphere" on .college campuses than can be perceived by examining the quantity of political protests.

Dartmouth has very rarely been the stage for a political demonstration and more rarely so of an illegal act in the name of a political cause. Moreover, as any true son of Dartmouth can attest, the Winter Term has a way of stifling all but the most hardy of political activists. It is difficult to hold a peace vigil when the thermometer is hovering around — 20 degrees. Yet, I still contend that there has been a perceptible change, subtle though it may be. Students are more introspective, cautious, and aloof. There is little political talk around the campus. One has only to walk through the stacks of Baker to become immediately aware that more people are studying. Overt political action has come to a virtual standstill.

The May Strike Committee (God rest its soul) faded into the horizon sometime over the summer and no similar liberal group has offered to take up its baton. Radicalism on both the left and the right is nowhere to be found on the Hanover plain. The SDS is dead or at least in a prolonged coma. That anagram is as significant to today's Dartmouth student as the WPA is. Dartmouth, for the first time since 1965, has a Young Americans for Freedom chapter, but at last count their membership totaled 13 students. The group is an outgrowth of the forty- member Strike Back Committee from last May. Skip Lewis, the president of the YAFfers (that's what they really call themselves), said that "a group of us got together last spring and decided that the College needed a balance of opinion." So far all the group has done is sponsor conservative speakers "to give the community and the students a look at an alternative viewpoint." YAF has presented speeches by J. Parker, a black conservative, and economist Milton Friedman. They also sponsored a debate between a conservative Jesuit priest, Father Daniel Lyons, and antiwar Dartmouth Professor Jonathan Mirsky.

This lack of political activity has been noticed by Dartmouth Trustee Chairman Charles Zimmerman. During a recent breakfast interview, Mr. Zimmerman told me that he was struck by this pall hanging over the campus. If this signifies an increased interest to work for change "within the system," he said, it is encouraging. However, if this quiet means that students have become apathetic and have "given up," he feels the prospects are "frightening." The malaise has even spread to student government. For two years now there has been no student government; only 16% of the student body voted in that last election and the plurality went to an imaginary candidate. During a recent interview, College Trustee John D. Dodd told a student reporter, "You really need some form of student leadership." Without it, he said, the Trustees can't get "real input" from students.

Academic departments have not remained untouched, either. Common is the lament of faculty members that they can't get students interested in departmental deliberations. Fraternity membership is at its lowest point in years and many fraternities are faced with imminent financial disaster. Raucous fraternity parties seem few and far between.

This brings us back to the questions: why is this happening and why now? Last May saw a high point in political activity. The "strike" was extremely constructive. It demonstrated that the college community could work together as a unit. A large segment of the community followed President Kemeny's advice to do some "soul searching" that week. Yet, on a national level, what did Dartmouth's activities and those nonviolent and violent actions across the country accomplish? The Administration has not changed its withdrawal timetable in Indo-China and students had very little effect on the election campaigns of 1970. Instead of being heeded, politically active students were used as an issue against the Democrats. The situation is analagous to the state of the campus (nationally) after the unsuccessful McCarthy campaign and the somewhat unsuccessful Moratoriums. Frustration follows. Only, now, that frustration has reached new heights. Students are not satisfied with the political atmosphere. They are quiet because they are frustrated and confused. After the tremendous effort expended last May, very little happened and students don't know what to do next. Contrary to what you may have read in the national press, the campus has not plunged itself into a new "Era of Romanticism." The campus for as long as I've known it has always been a romantic place. Just look at the history of the student movement in this country. It has all the earmarks of a romantic fantasy. What is happening now is that students are losing a little of that romantic zeal. The third question then becomes: what happens next? During his last press conference, I asked President Kemeny whether he thinks student activism is dying. He said, "I don't think I've been President long enough to be able to judge a pattern, but I think you should ask me that again at the end of May."

I do not mean to imply that there have been no issues on campus in this academic year. There have been, but none to compare with the major activity last year. Just as in the rest of the country, the major topic on campus is money. Tuition will go up $270 next year and with announced increases in room and board a Dartmouth education will cost more than $4000 a year. A tuition increase has become a yearly tradition for colleges across the country. (David Aylward '71, editor of TheDartmouth, told President Kemeny that the newspaper would print the same announcement each year and just change the date at the top.) The President feels that these increases cannot keep up much longer without turning students away. The increases bring in only a marginal amount of new revenue since a good percentage of the increase goes right back to students in the form of financial aid to pay for the tuition increase. (About 40% of the student body is on financial aid.) Mr. Kemeny feels that some new plan should be devised so students can pay for their own college educations after they start making a living. He proposes a "reverse social security" program. Under this plan, students would pay a certain percentage of their post-graduation incomes to the College until they had paid for their educations. His plan differs from the so-called "Yale Plan" in that the "reverse social security" program would be run by the Internal Revenue Service.

The Dartmouth student-operated radio station, WDCR, has once again started its annual "Let's Help" fundraising drive. This year it will support the Upper Valley Association for Retarded Children. In the past this drive has aided a hospital in Vietnam, Dartmouth's ABC Program, and handicapped children. WDCR was cited in the local newspaper, the Valley News, as the one enterprise at Dartmouth which "is quite adept at reaching out into the Upper Valley audience, rather than beaming its programs primarily to college-oriented listeners. WDCR's news staff attempts to cover area events and other programs are designed to interest and inform the entire region."

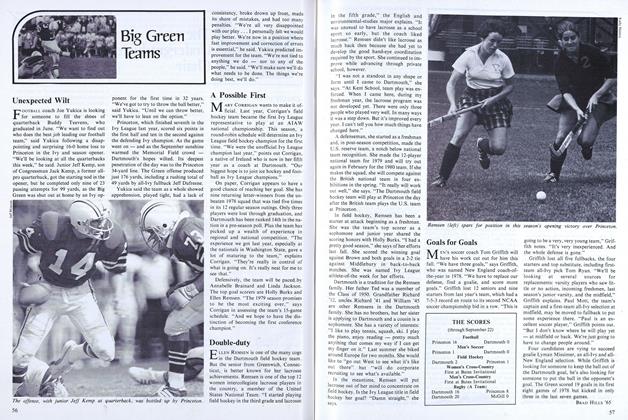

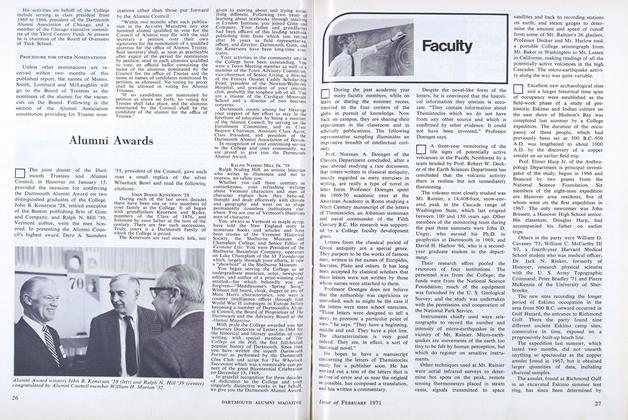

John Marshall '71, undergraduate member of the Dartmouth Alumni Council,gives his views on coeducation at the Council's January meeting.

"Standing Woman" by American sculptor Gaston Lachaise, a major gift to the College from Governor Nelson A. Rockefeller '30, is on view in the O. J. Buck Lobby of Hopkins Center. Considered the central work of Lachaise's life, "Standing Woman" began as an idealized portrait of a particular woman and ended as the personification of his vision of woman as goddess, mother, lover, and life principal itself. His own evaluation of his work was that it represented a continuing inquiry into the physical presence and emotional experience of woman. Lachaise was born in Paris in 1882 and came to America in 1906, working first in Boston and then in New York. He worked on "Standing Woman" from 1912 to 1927. At the time of his death in 1935, the year this cement cast of "Standing Woman" was executed, Lachaise was just beginning to be recognized as one of America's outstanding artists.

Steve Zrike is News Director forStation WDCR. An English major, hewas a delegate to the White Houseconference President Nixon held withcollege students from all sections of thecountry. He comes from Greenwich,Conn., and is the son of Raymond W.Zrike '44.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

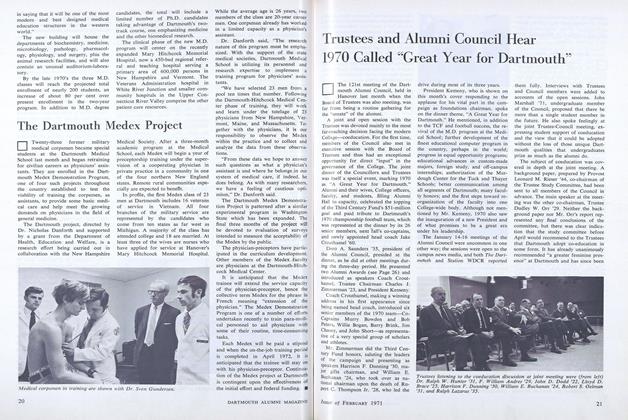

FeatureTrustees and Alumni Council Hear 1970 Called "Great Year for Dartmouth"

February 1971 -

Feature

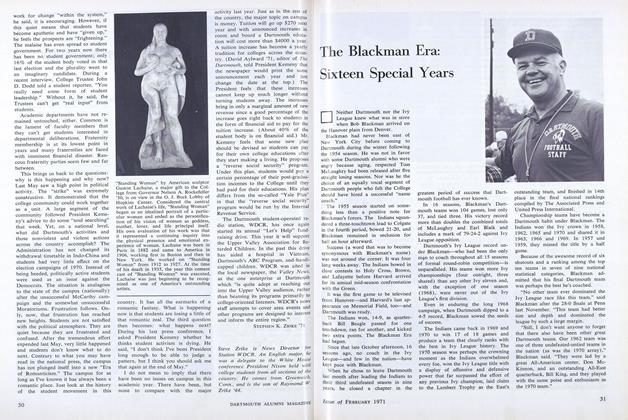

FeatureThe Blackman Era: Sixteen Special Years

February 1971 By JACK DE GANGE -

Feature

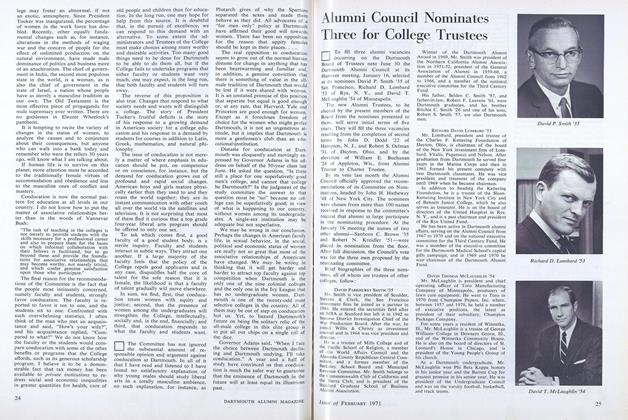

FeatureAlumni Council Nominates Three for College Trustees

February 1971 -

Feature

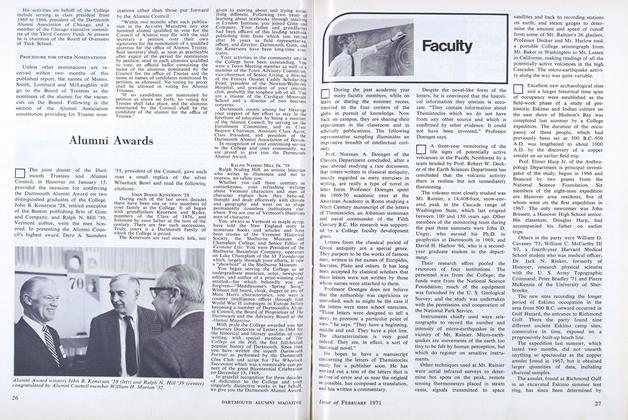

FeatureAlumni Awards

February 1971 -

Article

ArticleA Different View of Vietnam

February 1971 By STEPHEN HART '68 -

Article

ArticleFaculty

February 1971 By WILLIAM R. MEYER