Last month in this section we reported a few significant excerpts from President Dickey's talks to the alumni on the subject of American higher education and national security. In an address to the student body over Station WBDS on March 13, President Dickey spelled out in greater detail some of his views about the Communist problem as it affects the colleges. A post-deadline addition of the full text was not possible for this issue, but in the space still available here we want to print portions of the radio talk that seem to us to throw particularly helpful light on the questions of the relation of the Communist problem to teaching qualifications, to governmental investigative authority, and to the invoking of the Fifth Amendment of the Constitution.

"I feel that any institution owes a duty to itself and to the society which it serves to be clear about where it stands with respect to the qualifications and disqualifications of its members in a matter of this sort," President Dickey stated. He continued:

I think that most people would agree that higher education has prospered best in those great centers of learning where men have been chosen as teachers on the basis of their character and their demonstrated qualifications to teach a particular subject, without regard to the political affiliations of the individual. If I believed that membership in the Communist Party today involved merely a matter of minority and unpopular political affiliation, I should be clear that it was not, per se, a disqualification for a teacher. But I do not believe that this is in fact the case. Since 1947 I have been on record with the statement that I would not knowingly be a party to hiring a person who accepts the discipline of the Com- munist Party. I have seen nothing in the past six years which makes me doubt the correct- ness of that position. I took that position and I hold it now because I believe that the evidence is overwhelmingly persuasive that a person who accepts the obligations of membership in a conspiratorial group, committed to the use of deceit and deception as a matter of policy in the pursuit of its ends, is basically disqualified for service in an enterprise which is squarely premised on the functioning of a free and honest market place for the exposition, exchange, and evaluation of ideas. I remind you in this connection that evaluation often includes and requires rejection of ideas.

I think I ought to say to you at this point what I am sure most of you assume, and that is that we have no knowledge and I possess no information which leads us to believe that any member of our faculty or staff is subject to the discipline of such a conspiratorial group. If the unhappy day ever comes when we do possess such knowledge or information, you may be sure that I shall regard it as my duty to lay that information before the Faculty Committee Advisory to the President and the Board of Trustees and to raise the question whether on all the facts and circumstances as they are then known to us that person is qualified for service in this kind of enterprise.

President Dickey then turned to the matter of the public investigation of teachers and institutions of higher education, declaring:

A word ought to be said at this point about the relationship of an institution such as this to the activities of various public agencies which have concerned themselves or may concern themselves with problems of subversion in our national life. Over the years these activities have ranged all the way from the most responsible and painstaking judicial proceedings to some episodes of investigation which will not stand the test of American principles of fairness and justice, let alone wisdom. I cannot here attempt a review of all that has been done in this field, let alone foresee what may be done. I do think there are a few concrete points that can be made. First, I see no general basis on which colleges and universities can as a matter of legal right claim to be exempt from any proper governmental investigating authority. Secondly, I can see serious possibilities for misunderstanding from any blanket assertion which appears to suggest that men and women in this type of work should as a matter of general policy be beyond the proper reach of governmental authority. These institutions are not places of sanctuary from the law, and I think we do the cause of academic freedom a great disservice if, wittingly or unwittingly, we leave any doubt on that basic issue in the mind of anyone. It seems to me merely plain civic duty to say that any governmental authority which finds it necessary through proper procedures to identify and punish unlawful acts of subversion will have the support of every responsible institution in the land.

Believe me, I am not so naive as not to realize that the line between proper and improper procedures is often a blurred one and that there are always large areas for disagreement on such things, but, be that as it may, I still cannot believe that it is not our duty and our advantage in this business to be clear about the principle at stake. Beyond this principle there remain great questions of wisdom with respect to the advisability of investigating education, of the objectives of any such investigation, of the ways and the spirit in which any investigation is pursued and, of course, there are always the questions of by whom it is to be done and the qualifications of the investigator to investigate. These are difficult but very real questions. I doubt very much that they can be wisely answered in a vacuum. I can only say that every citizen, including particularly the man on this job, must reserve his right to speak whenever he feels such questions are at issue and are being wrongly answered and that his words can be effectively spoken in the interest of wiser answers.

In some detail President Dickey then explained why he does not hold with those who when testifying in investigations of subversion refuse to answer on Constitutional grounds:

It is in order here, I think, to say a word about a concrete issue which has come to the fore in various proceedings in this field. Some men either in the role of a witness or of a defendant have seen fit to invoke the privilege of the Fifth Amendment of the Constitution which provides that no person "shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself." These individuals have declined to answer presumably legally proper questions on the ground that their answer would tend to incriminate them. There can be no question of the right of an individual to invoke this privilege if he sees fit to do so, but the use of that privilege, in my opinion, at the very best raises serious questions about the qualifications of such a person for employment as a teacher. For reasons best known to the individual in question, and often only known to him, he has seen fit in a duly authorized judicial or legislative forum to assert that he will not answer a question because if he does so, his own words will tend to incriminate him.

It has seemed to many others, and it seems to me, that this is a very different situation from a man who is charged with wrong-doing by another's unproven words. I have not been able to escape the conclusion that anyone who invokes the protection of that privilege must accept the fact that by doing so, he, of his own choosing, calls into question the quality of his citizenship. Assuming a substantial question relevant to an individual's qualifications as a citizen and a teacher is at issue, it seems to me clear that any man must face the fact that the exercise of that privilege will involve serious consequences for him and any undertaking with which he is identified. A man who exercises this privilege either genuinely believes his words may incriminate him or he is using the privilege improperly. On the first assumption he, by his own action, avows the existence of what can reasonably be regarded as disqualification for service in a position of respect and responsibility; on the other hand, if he has invoked the privilege without truly believing that he needed its protection, he has acted falsely toward his government. Either way you take it, it seems to me we must say as as a matter of general policy that such a person has compromised his fitness to perform the responsibilities of higher education, and unless there is clear proof of peculiar circumstances in the particular instance which would make application of this policy unjust and unwise, the normal consequences of such disability must ensue. I am clear myself that I should feel it necessary in any such situation to take steps with the Faculty Committee and the Board of Trustees looking to either the suspension or the termination of the employment of such a person, depending upon the then existing and foreseeable circumstances.

In this connection it may be well to remind ourselves that this privilege is not historically or otherwise related to the protection of free- dom of speech or thought. Rather, it is a privilege which was designed to protect an individual in criminal proceedings against be- ing forced to bear witness against himself. As such, the privilege has a specific purpose which is properly narrowly confined as it cuts across the broad obligation of all citizens to answer responsively before duly constituted governmental tribunals. It should be noted that this privilege is not properly invoked for the purpose of protesting and taking issue with the legality of questions or for the pur- pose of contesting the propriety of a particu- lar proceeding and there is no doubt the privilege is not available to protect and support individual codes of honor which contravene the basic duty every citizen owes an authorized tribunal to answer the truth to all proper questions regardless of the consequences to others of his answer. Manifestly there is much that needs to be taken into account in reaching a conclusion in a matter of this sort and I suggest that any of you who are seriously interested in the background of the issue read a recently published article on the subject prepared by Professors Chafee and Sutherland of the Harvard Law School. I can do little more here than to state the conclusions as to general policy which I have reached after very conscientious thought. I do think it is of the utmost importance that such conclusions should be stated in an open and timely manner and that I have now tried to do.

After all aspects of these issues are weighed, do we not come back as a matter of policy to the proposition that American higher education cannot prosper unless it is carried on by men with honest and independent minds whose position before the laws of our society is such that they have no need to take refuge in any American tribunal behind a privilege against incrimination by their own words?

President Dickey concluded his talk to the students by reminding them "that there is another duty, a large, positive, pervasive duty that goes with the daily work of this business, and that is to see to it that the honest and independent-minded scholar who is deemed by his colleagues to be professionally competent is not driven from the market places of higher education because his views are unpopular in the eyes of his critics."

In advance of his late-evening broadcast over WDBS, President Dickey read the text to the faculty at a Faculty Coffee Hour in Dartmouth House that afternoon. This was followed by a question and discussion period.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

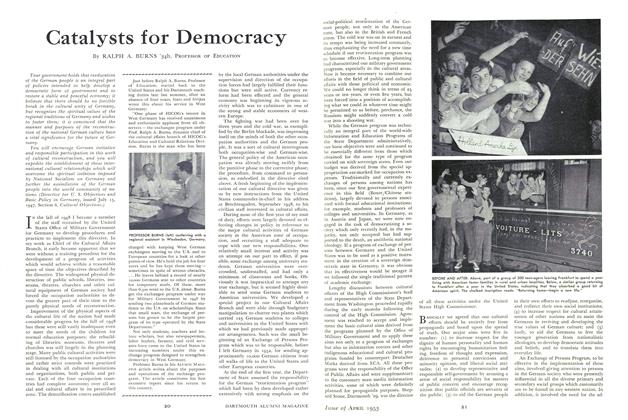

ArticleCatalysts for Democracy

April 1953 By RALPH A. BURNS '34h, -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

April 1953 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Article

Article1953 Alumni Fund Opens Campaign for $600,000

April 1953 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

April 1953 By KARL W. KOENIGER, HOWARD A. STOCKWELL -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

April 1953 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, GEORGE B. REDDING -

Class Notes

Class Notes1928

April 1953 By OSMUN SKINNER, GEORGE H. PASFIELD, WILLIAM COGSWELL