Know then thyself, presume not God to scan; The proper study of mankind is man. —Alexander Pope, Essay on Man

THE Dartmouth catalogue lists it as "Introduction to Human Relations" and says that "this course is designed to increase the student's understanding of social relations in contemporary society." That is the pedagogue's way of describing a unique course in the Dartmouth College curriculum.

Another way to describe it is in the words of a perceptive undergraduate. He says, "The difference between this course and all the others I've taken is the difference between putting a thermometer in a tub of boiling water to learn how hot it is and jumping in yourself to discover the same thing. That is really active learning."

He says the course is "like no other in three and one-half years of study in Hanover." And he adds, "The things done to you and with you make the work far more meaningful. It's a think course, a learningby-experience course that also involves a lot of homework, a lot of reading. It's not an easy course, either in the amount or type of work both in and out of class. The exams are tough and severely graded, and the questions asked do not always hew closely to the work of the course."

All this adds up to a brilliantly conceived, modern, frontal attack on a problem that by tradition has been met only indirectly in the education of the liberal arts student in American colleges. Its objective is to help students get more out of life by solving the following problem listed by the special faculty committee which established the course:

"College graduates who reflect upon their educational experience often recognize that a principal inadequacy is a failure to acquire understanding about the problem of living with other men and women. This inadequacy is also recognized by employers, who see brilliant individuals fail to achieve their potentials because of ineptness in working with colleagues."

The course consists of lectures, demonstrations and participation in laboratory sessions in small group situations. The catalogue further states:

"Its primary purposes are (1) to examine the structure of human groups (especially of small face-to-face groups) and the social forces generated within them; (2) to study the sources of differences between individuals in their effectivencess in inter-personal relations; (3) to develop in the student insight into human relations and into his potentiality for self-direction and growth."

" But a student in the course puts it just about as well, and a bit more succinctly:

"Nobody who is anybody does much in this world unless as a member of some group. The study of group dynamics is enormously rewarding, both from the personal standpoint of self-learning and from the study of others in the group."

Human Relations is under the direction of Prof. Cecil A. Gibb, Visiting Lecturer in Psychology. He is assisted by Professors Albert H. Hastorf of the Psychology Department; Francis W. Gramlich of the Philosophy Department; and Robert A. McKennan '25 and George F. Theriault '33 of the Sociology Department.

As can be seen from this staff, the course cuts across traditional departmental lines. It has to, because mankind is not organized in the same way that a college of liberal arts is broken up into special parts. More than that, the staff does not hesitate to bring in as visitors any persons who can make a contribution to the course.

The staff gives the lectures and sits in on the laboratory sessions. When the time for explanations comes, it is they who prompt or guide the direction of the discussions. But a visit to the course will find that it is the students themselves who are doing most of the talking, and the necessary thinking.

"All I do is ask a few questions to keep things going," says Professor Gibb. This is true, but his students say he has an uncanny ability to ask the "right" questions, the questions which promote the most mental effort on the part of the students around the circular conference table.

For the students who sit around that table it is an intriguing experience under the "glare of the limelight" in the laboratory, being tape recorded, studied through one-way observation glass, and watched by professors "who you always feel know more about you than you would like."

Everybody in this course feels vulnerable, according to one student, and all are careful of what they do. They know they are being projected into situations skillfully designed to demonstrate for them various human failings and passions—frustration, anger, hostility and withdrawal. What makes the whole thing fascinating is that they are the ones who are doing the demonstrating on each other.

They have a chance to observe the noisy pipsqueak or the professional leader, the man who places the act of leadership ahead of the task at hand, ahead of solving the problem or reaching the goal. They have a chance to observe the man who tends to lose his temper when under stress, or the man who becomes frustrated when he feels his ideas are not being welcomed. They can observe the man who withdraws from a group effort or abandons the goal when the going gets tough.

They have a chance to observe and analyze their own personalities under the stress of group participation. The course is a study of groups as such, of other persons in groups, and it is self-study of the individual in a group.

What's the use of all this? Go back to the undergraduate—"Nobody who is anybody does much in this world unless as a member of some group." He already is using information gained in the course in his relations in various student committees, dormitory bull sessions, even discussions over the dinner table.

From a purely practical standpoint, there is no question that this course will be useful to the aspiring young executive who wants to rise from assistant sales manager to executive vice president in the short span of ten years. Learning the psychology of how groups with shared purposes operate can be of enormous personal value in years to come. The point needs no elaboration that facts learned in an arbitrarily set up group, where emotions have a chance to play, apply as well to the board of directors of our largest corporations.

More than all this, however, is the very real personal value of self-examination. Thinkers through the ages have said again and again, as did Pope in his essay, that the proper study of mankind is man himself. And the best method for the individual is to start with self-examination. This course combines both studies in a manner that often leaves the students "gasping for breath" in a mental sort of way.

But like human nature, not all the classes are brilliant, not all of them come off as the instructor planned. A student declares that the course "is not intensive enough, the frictions are not brought into the open enough." But he recognizes that he cannot know what is going on in the minds of others. A laboratory session which for him is a waste of time may be tremendously absorbing for a student across the room who is deeply involved in a mental and emotional struggle.

The laboratory sessions involve groups of students who may be assigned a common task—to solve a problem, to discuss a question and reach a group conclusion, or merely to elect a leader and form into committees before attacking a problem.

Questions are posed by the instructors and may range from the purely artificial to those of intense and immediate importance. One group this year, for example, was asked to examine student-faculty relations at Dartmouth, to supply facts and recommendations to a member of the class who is also a member of the Undergraduate Council.

This question is of immediate importance because the student is an advisory member of President Dickey's commission to study student life at Dartmouth. Another problem involved the location of a public school with relation to proposed bus routes. This problem could not be solved in a satisfactory manner, but the students taking part did not know it. They went through various degrees of frustration, anger and abandonment of the task, while other members of the class observed them through the one-way windows in the wall of the laboratory.

Another problem, assigned first to one half a class and then to the other half, involved construction of a figure with a child's Tinker Toy. One group was given a problem that was difficult but which could be solved within the time allowed. The other group was given a task that could not possibly be completed.

"You would be amazed how much genuine mental effort is involved even in an artificial situation," says another student. "One reason is that the course, the lectures and the laboratory sessions are serious affairs. At times they may be informal, but you never forget why you are there, and that the others are there for the same reason—to learn something about people, including yourself."

If you ask the professors, they will tel! you that the students are the ones who actually run the course—and they do. No outsider can gain admittance to the laboratory sessions without permission from the students. Students in the laboratory cannot be recorded or observed through the windows without their prior knowledge and permission.

They set their own rules, and they pretty much establish the tone of the course. It is in truth a study of the group process at work, and the course runs itself by that very group process. It is the only course at Dartmouth in which the mechanics of operation are so set up, and for the students who take part it is a stimulating and rewarding experience.

All this is possible through the gift of $50,000 from Mr. L. J. Montgomery of Las Vegas, Nevada, an uncle of Kenneth F. Montgomery '25. In the summer of 1951 a committee of the faculty headed by Dean Donald H. Morrison began to develop a course plan. The instructional and laboratory techniques to be used were tried out in other classes and a study as made of methods used in other institutions also experimenting in the teaching and demonstration of inter-personal relations and group behavior.

And now Dartmouth finds itself pioneering at the undergraduate level in a new field that in a direct, contemporary way helps American students today to study one of the most important ingredients of the liberal arts curriculum, themselves and those around them.

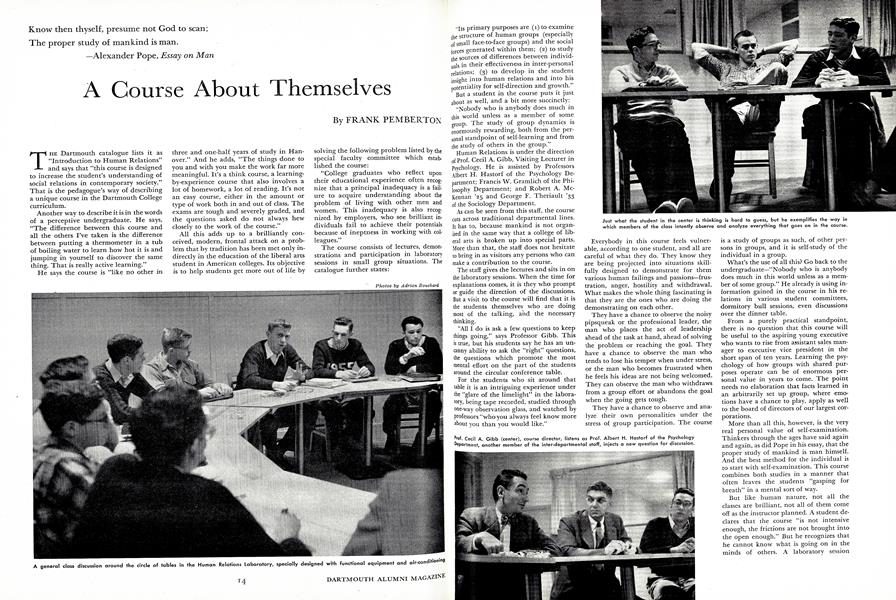

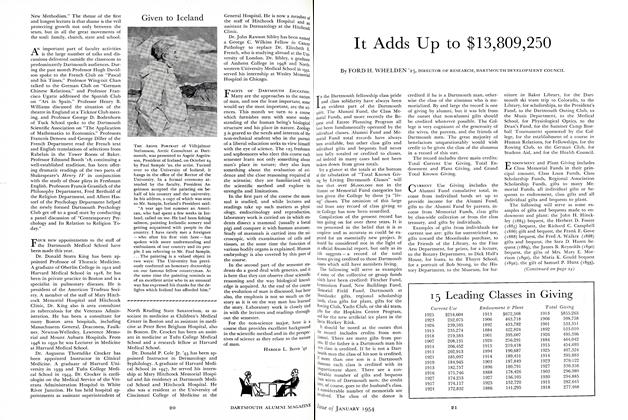

A general class discussion around the circle of tables in the Human Relations Laboratory, specially designed with functional equipment and air-conditioning

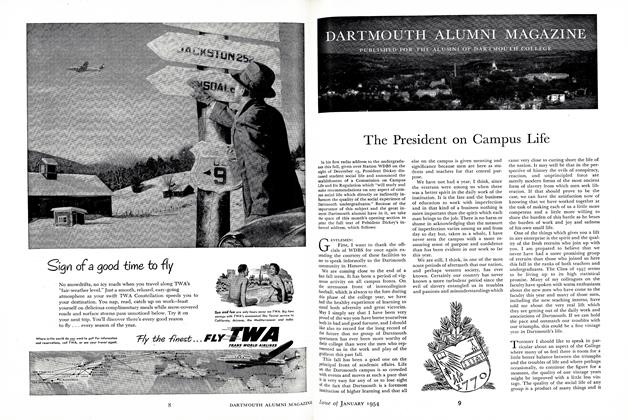

Just what the student in the center is thinking is hard to guess, but he exemplifies the way in which members of the class intently observe and analyze everything that goes on in the course.

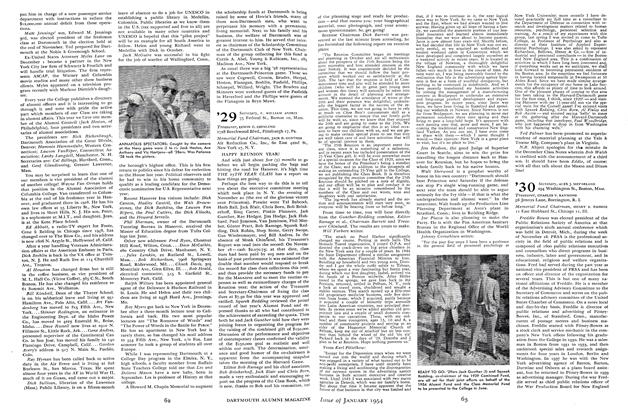

Through the looking-glass is actually possible in the Human Relations Laboratory. In the large conference room (left) the observation glass serves as a mirror. In an adjoining room (right), where tape-recording equipment is located, two members of the staff are observing the discussion through the same glass.

Through the looking-glass is actually possible in the Human Relations Laboratory. In the large conference room (left) the observation glass serves as a mirror. In an adjoining room (right), where tape-recording equipment is located, two members of the staff are observing the discussion through the same glass.

Group attacks on tough problems provide a lively means of studying inter-personal relations. Here a six-man team undertakes to locate a public school with relation to various proposed bus routes.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe President on Campus Life

January 1954 -

Feature

Feature"Red" Rolfe '31 to Return As Director of Athletics

January 1954 By C.E.W. -

Feature

FeatureIt Adds Up to $13,809,250

January 1954 By FORD H. WHELDEN '25 -

Feature

FeatureNine-Man Council Charts Course for Development

January 1954 By GEORGE H. COLTON '35 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

January 1954 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, RICHARD P. WHITE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

January 1954 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, EDWIN C. CHINLUND, JACK D. GUNTHER

FRANK PEMBERTON

-

Article

ArticleThe 1954 Commencement

July 1954 By FRANK PEMBERTON -

Feature

FeatureThey're Putting the D in Debating

April 1955 By FRANK PEMBERTON -

Feature

FeatureOPERATION BOOTSTRAP

June 1955 By FRANK PEMBERTON -

Article

ArticleThe 1955 Commencement

July 1955 By FRANK PEMBERTON -

Article

Article150,000-Volt Accelerator Aids Nuclear Studies in Physics Lab

October 1955 By FRANK PEMBERTON -

Feature

FeatureThe 1956 Commencement

July 1956 By FRANK PEMBERTON

Features

-

Feature

FeatureWHY COLLEGE ?

December 1973 -

Feature

FeatureOut of the Amazon

MAY | JUNE 2018 By ANDREW FAUGHT -

Feature

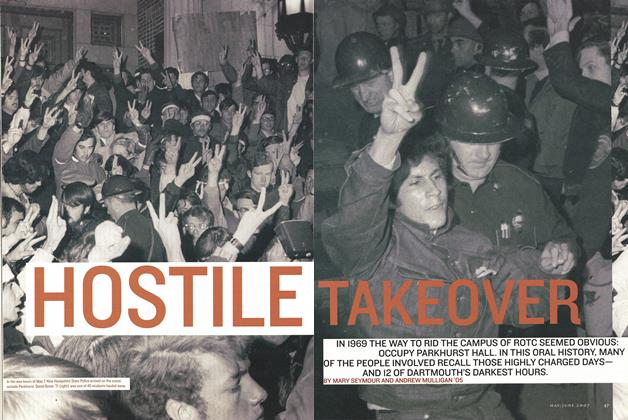

FeatureHostile Takeover

May/June 2007 By MARY SEYMOUR AND ANDREW MULLIGAN ’05 -

Feature

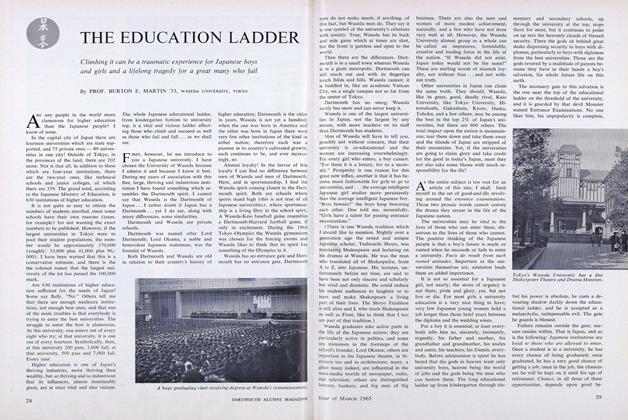

FeatureTHE EDUCATION LADDER

MARCH 1965 By PROF. BURTON E. MARTIN '33 -

Feature

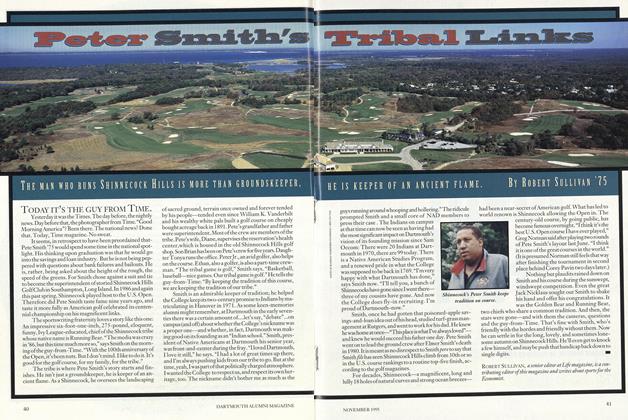

FeaturePeter Smith's Tribal Links

Novembr 1995 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

FEATURE

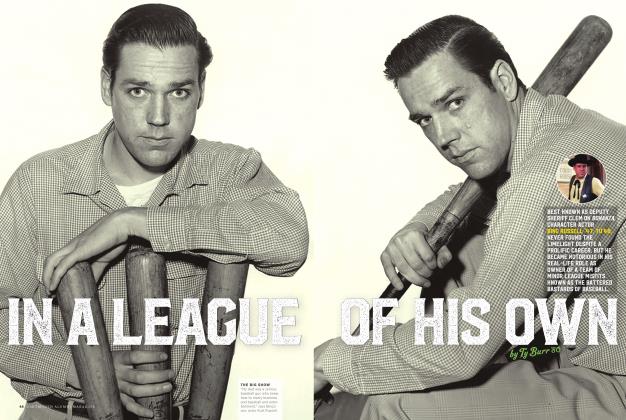

FEATUREIn a League of His Own

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2016 By TY BURR ’80