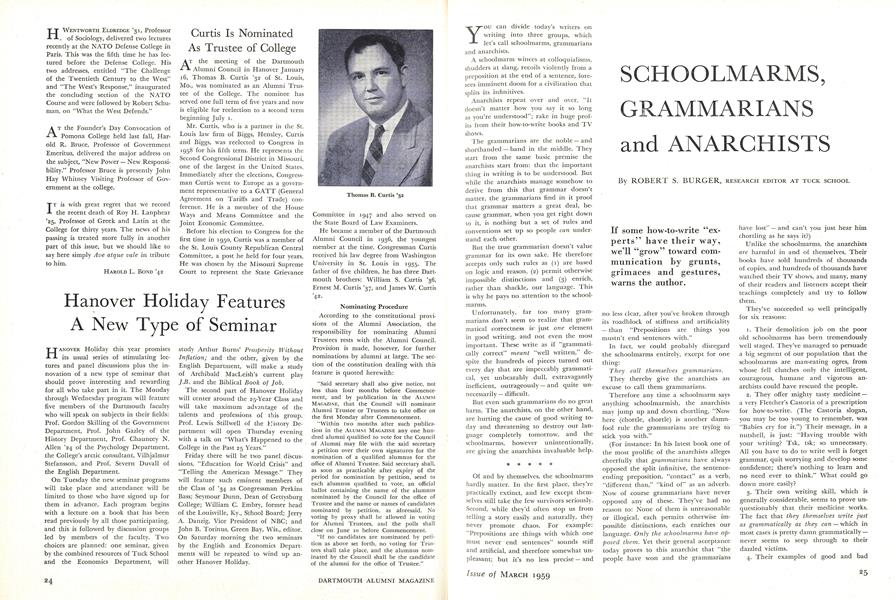

If some how-to-write "experts" have their way, we'll "grow" toward communication by grunts, grimaces and gestures, warns the author.

RESEARCH EDITOR AT TUCK SCHOOL

You can divide today's writers on writing into three groups, which let's call schoolmarms, grammarians and anarchists.

A schoolmarm winces at colloquialisms, shudders at slang, recoils violently from a preposition at the end of a sentence, foresees imminent doom for a civilization that splits its infinitives.

Anarchists repeat over and over, "It doesn't matter how you say it so long as you're understood"; rake in huge profits from their how-to-write books and TV shows.

The grammarians are the noble - and shorthanded - band in the middle. They start from the same basic premise the anarchists start from: that the important thing in writing is to be understood. But while the anarchists manage somehow to derive from this that grammar doesn't matter, the grammarians find in it proof that grammar matters a great deal, because grammar, when you get right down to it, is nothing but a set of rules and conventions set up so people can understand each other.

But the true grammarian doesn't value grammar for its own sake. He therefore accepts only such rules as (1) are based on logic and reason, (2) permit otherwise impossible distinctions and (3) enrich, rather than shackle, our language. This is why he pays no attention to the schoolmarms.

Unfortunately, far too many grammarians don't seem to realize that grammatical correctness is just one element in good writing, and not even the most important. These write as if "grammatically correct" meant "well written," despite the hundreds of pieces turned out every day that are impeccably grammatical, yet unbearably dull, extravagantly inefficient, outrageously - and quite unnecessarily -difficult.

But even such grammarians do no great harm. The anarchists, on the other hand, are hurting the cause of good writing today and threatening to destroy our language completely tomorrow, and the schoolmarms, however unintentionally, are giving the anarchists invaluable help.

Of and by themselves, the schoolmarms hardly matter. In the first place, they're practically extinct, and few except themselves stilltake the few survivors seriously. Second, while they'd often stop us from telling a story easily and naturally, they never promote chaos. For example: "Prepositions are things with which one must never end sentences" sounds stiff and artificial, and therefore somewhat unpleasant; but it's no less precise - and no less clear, after you've broken through its roadblock of stiffness and artificiality - than "Prepositions are things you mustn't end sentences with."

In fact, we could probably disregard the schoolmarms entirely, except for one thing:

They call themselves grammarians.

They thereby give the anarchists an excuse to call them grammarians.

Therefore any time a schoolmarm says anything schoolmarmish, the anarchists may jump up and down chortling, "Now here (chortle, chortle) is another damnfool rule the grammarians are trying to stick you with."

(For instance: In his latest book one of the most prolific of the anarchists alleges cheerfully that grammarians have always opposed the split infinitive, the sentenceending preposition, "contact" as a verb, "different than," "kind of" as an adverb. Now of course grammarians have never opposed any of these. They've had no reason to: None of them is unreasonable or illogical, each permits otherwise impossible distinctions, each enriches our language. Only the schoolmarms have opposed them. Yet their general acceptance today proves to this anarchist that "the people have won and the grammarians have lost" - and can't you just hear him chortling as he says it?)

Unlike the schoolmarmS the anarchistsare harmful in and of themselves. Their books have sold hundreds of thousands of copies, and hundreds of thousands have watched their TV shows, and many, many of their readers and listeners accept their teachings completely and try to follow them.

They've succeeded so well principally for six reasons:

1. Their demolition job on the poor old schoolmarms has been tremendously well staged. They've managed to persuade a big segment of our population that the schoolmarms are man-eating ogres, from whose fell clutches only the intelligent, courageous, humane and vigorous anarchists could have rescued the people.

2. They offer mighty tasty medicine a very Fletcher's Castoria of a prescription for how-to-write. (The Castoria slogan, you may be too young to remember, was "Babies cry for it.") Their message, in a nutshell, is just: "Having trouble with your writing? Tsk, tsk; so unnecessary. All you have to do to write well is forget grammar, quit worrying and develop some confidence; there's nothing to learn and no need ever to think." What could go down more easily?

3. Their own writing skill, which is generally considerable, seems to prove unquestionably that their medicine works. The fact that they themselves write justas grammatically as they can - which in most cases is pretty damn grammatically- never seems to seep through to their dazzled victims.

4. Their examples of good and bad writing are extraordinarily well chosen: That is, the bad writing is horrible, the good writing excellent. And people fail to realize that the trouble with the horrible pieces is not their grammatical correctness, and that the good pieces - like the anarchists' own - are generally perfectly grammatical.

5. Most of their premises are absolutely and unmistakably sound. And they argue so ingeniously and self-confidently that people never get around to noticing that their premises don't justify their conclusions.

6. People are hungry to write better.

Now let's look at some of the anarchists' arguments.

PREMISE I: A language must grow to stay healthy. Absolutely true - and, incidentally, accepted by all sensible people, however the anarchists may try to claim it as their private doctrine. But to conclude from it that anything that happens to a language is for the best - and, consequently, that grammar doesn't matter- you have to disregard two other truths, each of them just as self-evident and significant as the first:

1. Not all growth is good growth. It's good when a 20-inch, 8-pound baby becomes a 72-inch, 190-pound man. But it's bad when a 120-pound housewife becomes a 220-pound housewife. This growth has done nothing for her except lower her efficiency, make her less attractive, reduce her life expectancy. This is why she spends so much of her time regretting it and trying to ungrow, and ungrowing is always much, much harder than not growing would have been.

The wrong kind of growth will affect a language the same way: It will lower its efficiency, make it less attractive, even reduce its life expectancy. And it will always be extremely hard to undo.

And a phrase like the prepositional "due to"-far and away the anarchists' favorite preposition, though they don't use it themselves - represents just this kind of growth. It does nothing good for the language; it conveys no meaning that "because" or "because of" can't convey as well, and rarely one that a verb-centered construction couldn't convey better. If it gets permanently into our language it will just fasten itself onto the language's waistline and hang over the language's belt unto death.

This is not, let me stress, an argument against growth. Grammarians want our language to grow - but they care how it grows.

2. Not all change is growth. A man changes when he has a hand amputated- but he weighs less, not more, as a result. And he's a lot less efficient.

And when our language loses something like the shall-will distinction- which, let's face it, is gone forever —it hasn't grown. It's suffered an amputation. We used to have in "shall" and "will" two slightly different words, each with particular, precise meanings. Now we have one, which will have to do two jobs, and which consequently will do neither quite as well as we may sometimes want it to.

It's as if - to change similes abruptly- we once had a chisel and a screw driver, and we lost the screw driver, so now we have to use the chisel to drive screws. It will never drive screws as well as the screw driver did, and soon it will chisel less well than it used to.

This isn't an argument against change, either. It's not even an argument against surgery; grammarians won't object at all to surgery that removes a linguistic cyst, cancer or inflamed appendix. But we'd like to save all the language's limbs, digits and vital organs.

PREMISE II: Written language is best when it sounds like spoken language. Also true, and also accepted by all sensible people. But it does not support the conclusion that the way to write is just to open a faucet and let the words pour out. Why not?

Because words that just pour out - your spoken words, for example - are highly inaccurate and inefficient. When you talk you hem, you haw, you go off on tangents, you stop, back up and start over, you repeat, you leave things out, you get lost in your own sentences. This doesn't matter - much - when you're talking to someone, because you can hold his interest and clarify your message for him in various nonverbal ways; and he can say "How's that again?" when he doesn't understand you, and then you can rephrase your message to make it clearer. But all a reader has from you is bare black words on a white page. He can't hear your voice rise and fall, can't see your eyes, your facial expressions or your gestures, and, above all, can't interrupt when he doesn't understand you. If you write the way you talk, therefore, you'll:

1. Bore people.

2. Waste people's time.

3. Confuse and misinform people.

4. Alienate people.

No, sir; a writer has to work like the devil for accuracy, efficiency and all the other characteristics of good writing- and then, after achieving all these, make his language sound - more or less - like spoken language. Which is quite different from what the anarchists tell you.

PREMISE III: Pomposity, rigidity, unnecessary formality hurt your writing. Also true. But:

Most of today's pompous, rigid and excessively formal writing is ungrammatical. People with confidence in their grammar can write naturally and informally. To prove this: Where, today, do you most often find the anarchists' favorite preposition?

In a sentence like:

We regret that it is necessary for us to inform you that we are unable to ship your order of the 25th of January due to the fact that we have not yet received from you payment for the order shipped you by us on the 17th of December.

Now of course this sentence suffers from much more than just the grammatical error in "due to." But - and this is highly significant—"due to the fact that" is not just ungrammatical here; it's also painfully inefficient, pompous and hyperformal. Replace it with the simple, informal, grammatically correct "because" and you've not only corrected the sentence; you've also improved it.

But, say the anarchists triumphantly, the sentence is still terrible. The man should have written:

Sorry; we can't ship your latest order till you pay us for the last one we did ship.

I agree completely. But this proves my point, not theirs. The much better version is - among other things - perfectly grammatical.

And in case anyone wonders how much we've helped this message by eliminating the grammatical error, let's reinsert it:

Sorry; we can't ship your latest order due to the fact that you still haven't paid us for the last one we did ship.

This is better?

But so far I've proved (I think) only that the anarchists are wrong. I haven't yet proved that they're hurtful.

So now let's see how they're hurtful what they're doing to us today and what they may do to us tomorrow.

This is how things stand today:

1. Most nonprofessional writing— in business, in government, in the sciences —is pretty terrible. This state of affairs isn't new. But the situation is somewhat more serious than it used to be, for two reasons: More people are writing than ever before, and writing is being taught less effectively than it used to be. (It never used to be taught well, but this is irrelevant.)

2. Happily, many people have recognized the situation; they've decided they need to write better, and they want their employees to write better. This is why so many buy the anarchists' books - and also, if you'll pardon" me, why some come to my American Management Association seminars on writing.

3. Today's writing is bad for a number of specific reasons, which I call the sixteen writing "diseases." I know people can improve their writing by curing themselves of these diseases; I've not only testimonials, but also examples, to prove it.

4. Incorrectness is only one of these diseases, and probably one of the less important. But it is a disease.

5. The anarchists not only deny this; they actually recommend it as a cure. (Almost as the only cure.)

6. Besides discouraging improvement in one respect, therefore, they hinder people -people who are hungry to write better - from improving in any respect.

Q. E. D.

To see what may happen tomorrow, let's just look at the word "literally." (Some other words could serve just as well, and so might some punctuation marks, but no matter: We'll look at "literally.")

You see it misused every day. (The an- archists, of course, will object that "misused" reflects a personal value judgment, but never mind that, either.) When Sam Snead shoots a 64, you know some sports writer will report that "Snead literally burned up the course."

One of our sports writers did exactly this while I was working for a fairly big Midwestern newspaper, not many years ago. A year or so later, by which time I'd switched to teaching journalism at a Midwestern university, I told some of my students the story. It didn't get quite the reaction I'd expected. Instead, no one said anything for a moment; then a boy asked, "What difference did it make? After all, everybody knew what he meant."

This is what difference it made

First, if "literally" means "figuratively," what word will you use when some future Snead burns up a course with matches and kerosene?

Second, if "literally" means "figuratively," why can't "black" mean "blue," "no" mean "yes," "recognize" mean "crustacean" and "cumbersome" mean "milk shake"?

If you say the reason is that people wouldn't understand you, you're trapped. If you got out of your chair and walked right down to the nearest drugstore and ordered a chocolate cumbersome, you'dget a chocolate milk shake - if you tried hard enough.

First, of course, the clerk would look at you blankly and say, "I beg your pardon?"

But you'd just repeat, "A chocolate cumbersome, please."

Then he'd say, "What's that?"

And you'd say, "A chocolate cumbersome, a chocolate cumbersome!" And then all you'd have to do to get your message across would be to point to the milkshake mixer.

You could even get a strawberry milk shake, if that was what you wanted, by ordering a chocolate cumbersome. This would be only slightly more difficult.

So people would understand you.

But - and this is the point - when you use words this way you have to work awfully hard to be understood.

So when the time comes when any word may mean just what the user wants it to mean, as opposed to what people agree that it means, people will still be able to understand each other. But communication by words will be so tough that we'll just stop using words. We'll be able to communicate much more easily by grunts, grimaces and gestures - and in writing, by pictures.

I'm not kidding, not exaggerating. This is the logical, predictable final stage if the anarchists have their way.

This is what we should "grow" toward?

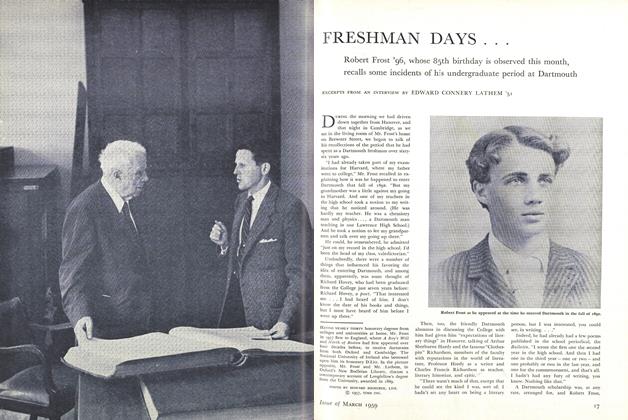

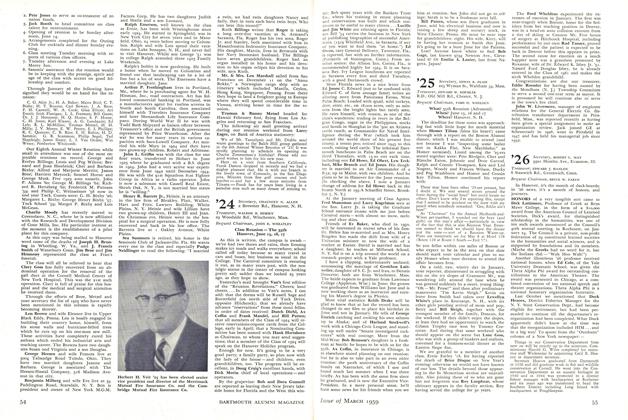

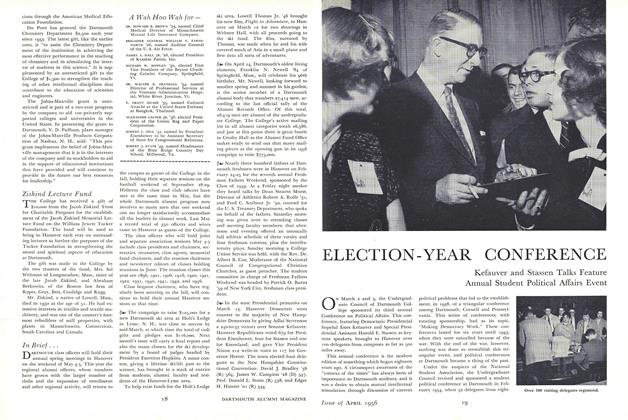

Six Dartmouth alumni now serving in the U. S. Congress are (l to r) seated: Thomas B.Curtis '33 of St. Louis, member of Ways and Means and Joint Economic Committees; EdgarW. Hiestand '10, Altadena, Calif., member of Committees on Banking and Currency and Education and Labor; Perkins Bass '34, Peterborough, N. H., member of Committees on Bankingand Currency and Astronautics and Space Exploration; Standing: Robert R. Barry '37T,Yonkers, N. Y., member of Committee on Post Office and Civil Service; Edwin B. Dooley '26,Mamaroneck, N. Y., member of Committee on Public Works; and John S. Monagan '33,Waterbury, Conn., member of Committee on Government Operations.

Robert S. Burger, author of this article, was with the Louisville Courier-Journal before he came to Tuck School in 1956 as assistant professor and research editor. He earlier taught journalism at Southern Illinois University. Under the sponsorship of the American Management Association, he has been conducting a series of New York seminars on how to write financial reports.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

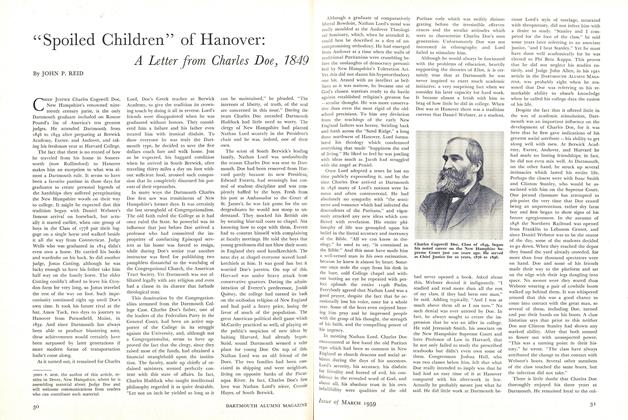

FeatureFRESHMAN DAYS...

March 1959 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51 -

Feature

Feature"Spoiled Children" of Hanover: A Letter from Charles Doe, 1849

March 1959 By JOHN P. REID -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

March 1959 By THOMAS E. SHIRLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, RICHARD P. WHITE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1950

March 1959 By SCOTT C. OLIN, SIMON J. MORAND III -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

March 1959 By ROBERT L. MAY, EDWARD J. HANLON, BRUCE W. EAKEN -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

March 1959 By CHESTER T. BIXBY, CHARLES H. JONES, TRUMAN T. METZEL

Features

-

Feature

FeatureProfessor John Stearns '16: Rara Avis Una

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Eddie Chamberlain '36 -

Feature

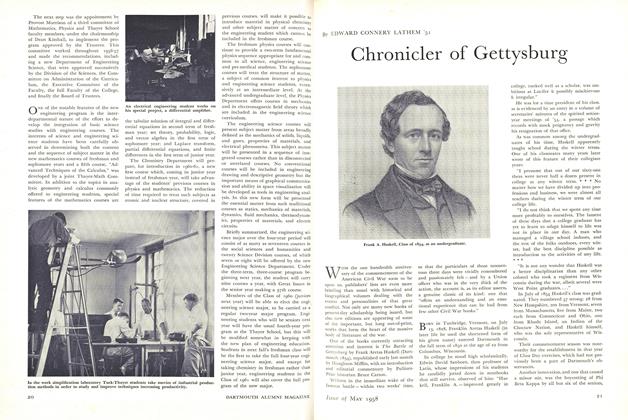

FeatureChronicler of Gettysburg

May 1958 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51 -

Feature

FeatureOf Sun-Gazers and Seal-Hunters

JAN./FEB. 1978 By James L. Farley -

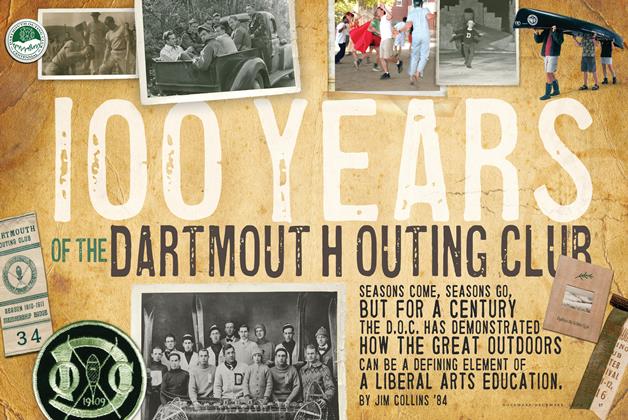

Cover Story

Cover Story100 Years of the Dartmouth Outing Club

Nov/Dec 2009 By Jim Collins ’84 -

Feature

FeatureThe U.S.-Canadian Relationship

DECEMBER 1972 By JOHN SLOAN DICKEY '29 -

Feature

FeatureELECTION-YEAR CONFERENCE

April 1956 By ROBERT H. GILE '56