My speech today may contain a few familiar precepts. However, precepts become familiar because they embody certain truths, and I think the time has come for us to rediscover some of these truths.

Now all of us here today have heard something of the high-mindedness of today's college students. We know of their opposition to war, their hatred of sham, their sympathy for the world's hungry. Indeed, these attitudes show a rare and praiseworthy concern for one's fellow men.

But after all, it's quite a simple matter for us to love, for example, a starving Latin American peasant, simply because we have never had to live with one. It is even easier for us to love several thousand starving Latin American peasants. Our idealism is really put to the test, though, when we are called upon to love our neighbor. By "neighbor" I mean not only a starving Latin American peasant. I mean the fellow in the seat next to you, too.

How often we fail to remember this! Time and again, the noblest of abstract principles retreats when confronted with the concrete situations which we are called upon to face in our everyday lives. Does it make sense for a mother to get herself arrested during an anti-war protest, if, as a result, her children are left to their own devices? Indeed, we often lavish so much of our concern on those who are thousands of miles away that we have none left for those who live near us.

This fact is inescapable: that each and every one of us has a duty toward all human beings. It is necessary, however, to make clear exactly what this duty consists of. One could spend quite a bit of time listing his duties to his fellow man, but they can be summed up in one word—charity.

We must be careful in interpreting this word, though. Too often one thinks of a charitable spirit only in the general sense—goodwill toward all men. There is, on the other hand, what is perhaps a more important connotation and it is, as I have already pointed out, a specific one—goodwill toward one's neighbors and toward those in one's immediate vicinity.

We see at once that specific charity is a much harder responsibility to fulfill than general charity. While a general spirit of charity may involve monetary contributions to worthwhile causes and the open espousal of lofty principles, a specific one entails actually living up to those principles. How many of us have neighbors whom we do not know, or to whom we are perhaps even unfriendly? How many of us have ever seriously considered the idea of showing charity toward the wealthy as well as the poor? The answers to these questions might well indicate just how far we are from attaining our goals.

The results of our "specific" charity may also seem somewhat less rewarding. It is much easier to take pride in stopping a war in which thousands of people are being killed than in helping our next-door neighbor; but yet, if this world were perfect and if charity in specific were not lacking, charity toward those whom we have never seen or known would not be necessary at all. Thus we should direct much of our effort within our immediate sphere of influence, where it can have the strongest effect.

An English proverb states: "Every man's neighbor is his looking-glass." I doubt, though, that there is one of us here today who cannot think of a few neighbors or friends in whom he would not care to imagine that he is being reflected. Every time we disparage someone with whom we often come in contact, we are, to some extent, also discrediting ourselves.

In order to live up to our new, more localized conception of charity, we must come to one more realization. I think none of us here today would object to the maxim: "Love thy neighbor as thyself." But we forget something as we say this. "Love thy neighbor—as thyself." After all, is it not true that all selves are worthy of love? Do not get me wrong; I make no plea for shallow egotism—no morality worthy of the name can be erected on such a rotten foundation. I have something else in mind. Perhaps C. S. Lewis said it best: "Each man, in the long run [ought] to be able to recognize all creatures (even himself) as glorious and excellent things." In fact, I seriously question that one can show true charity toward others without having reached this realization.

Believe me, it is not easy to fulfill one's duty to one's self and others, but it is a task that none of us can dare to shirk. To wail, "I have found it hard to live," or to cry, "I am a mad person in a sane world" and leave it to the world to set us right, is a complete abdication of our responsibilities as human beings. Self-pity leads nowhere. Better and braver by far are those who willingly and joyfully accept life and the responsibilities that life entails.

I conclude by asking that we do the hardest thing in the world: let us face these responsibilities and carry out in full our duty toward all men, in particular those closest to us. Understanding our fallibility as human beings, let us meet failure in ourselves and others with good cheer. The just man falls seven times and rises again.

So "not fare well, but fare forward." May God bless you and your families in the years to come.

Ross Kindermann, who resides in Fox Point, Wis., was grad-uated summa cum laude and with valedictory rank amongthe men of '72. He has won a graduate fellowship for thestudy of probability and statistics at the University of Illinois.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

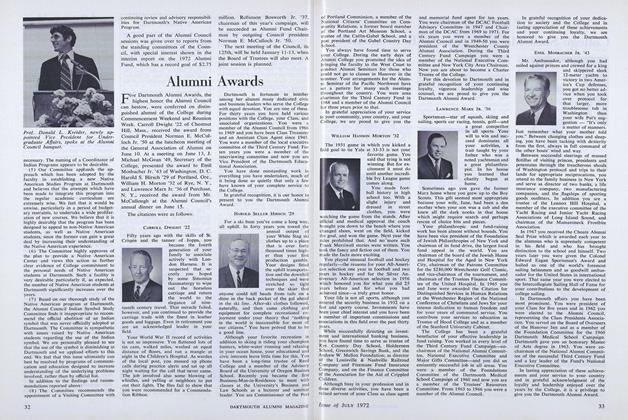

FeatureAlumni Awards

July 1972 -

Feature

FeatureCOMMENCEMENT 1972

July 1972 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Feature

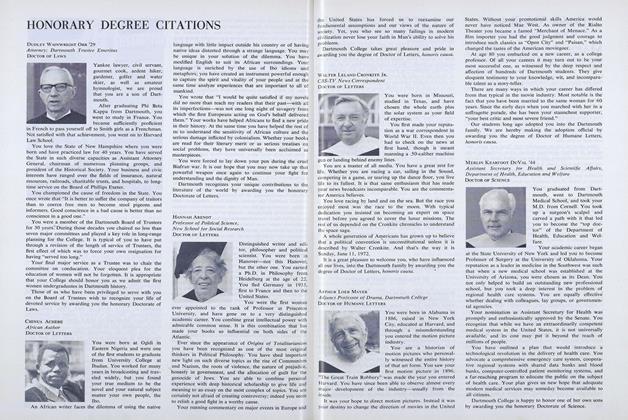

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

July 1972 -

Feature

FeatureCollege Staff Members Reach Retirement

July 1972 By J.D. -

Feature

FeatureAlbert I. Dickerson '30 1908-1972

July 1972 By C.E.W. -

Feature

FeatureVincent Jones 52 Heads Alumni Council

July 1972

Features

-

Feature

FeatureHarvey Hood '18 Retires as Trustee

JULY 1967 -

Feature

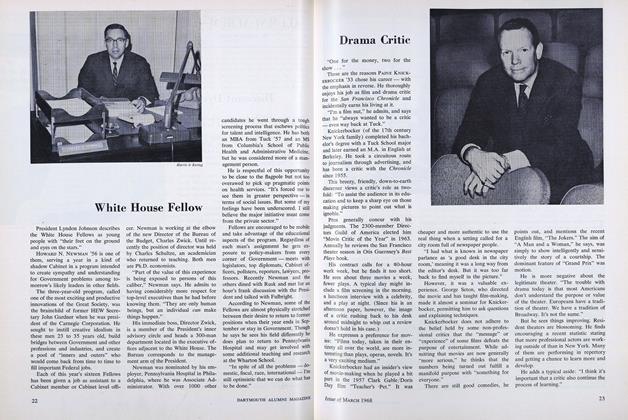

FeatureWhite House Fellow

MARCH 1968 -

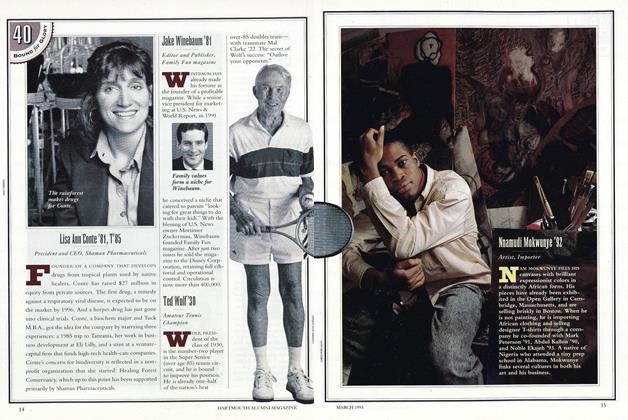

Cover Story

Cover StoryLisa Ann Conte '81, T'85

March 1993 -

Cover Story

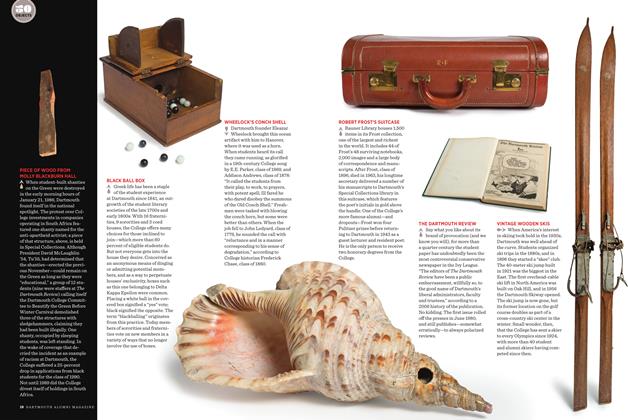

Cover StoryWHEELOCK’S CONCH SHELL

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

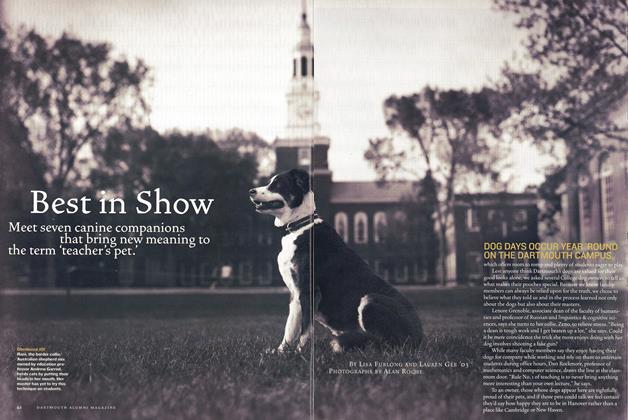

FeatureBest in Show

Mar/Apr 2004 By Lisa Furlong and Lauren Gee ’03 -

Feature

FeatureThe Quiet Good Man

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Young Dawkins '72