In his Convocation Address, opening theCollege's 186th year, President Dickey asserts:"Live Free or Die" is the law of intellectual life

GENTLEMEN of the College:

We come together this morning in Convocation to take our places side by side as this historic American liberal arts college gathers itself for another year — its 186th — in the endless pursuit of education.

We who come back as teachers and upperclassmen are warmed and borne up by our return to that belonging which is the Dartmouth fellowship. To all the others who join us for the first time today, including especially the men of the Class of 1958, we promise you this: you are more than welcome, you are now one of us.

And may I say an especially warm word of appreciation and admiration to the men of the upper classes who planned and who manned the orientation program this year. In my opinion, there is no campus in America where men have been more maturely and wisely introduced to college life than on the Dartmouth campus this year; and for that very great service Dartmouth owes you upperclassmen great appreciation.

A special word is due the men of 1958: as a group, at least up to now, you have had less shrink in you than your predecessors and as a result you are perhaps the largest freshman class and, my hand reminds me, certainly one of the most muscular ever to shake the hand of the President at matriculation. May it continue so even unto your fiftieth reunion. From here on out, however, our eyes will be on your size as individuals and not as a class. Over the next four years individual growth is the magic formula for "sanforizing" the Class of 1958.

In recent years I have spoken on this occasion about some of the personal qualities that bear mightily on the will and capacity of a boy to raise a good man from whatever seed has been given him for the growing. The words are commonplace: humility, loyalty, integrity, a cooperative and moral outlook, manners fit for a man, and that ultimate discipline of self we call maturity. The words have been said at other Convocations, but the relevance of these qualities is timeless except that for you and me the time is now, the place is Dartmouth, and the doing of these things must be yours at every point where you touch Dartmouth and she touches you.

I say these things flatly, gentlemen, because it is only such men Dartmouth dare endow with the power of higher learning and only unto such hands ought her purposes be entrusted. I must tell you, and remind myself, these are not mere sentiments of convenience; they are the conditions and commitments which sustain the existence of this College. Without them it would soon be empty of purpose and without purpose it would meet the deserved fate of the derelict it had become. It would be sunk without a trace as a menace on the seas of a free and moral society.

Purpose, like the past of which Shakespeare spoke, is prelude; in any undertaking it is the prerequisite to policy and program. Purpose is the track on which human action moves and is given direction and, as every thoughtful person soon knows, it is not a single track in any man or human institution. We also soon learn that purpose is a personal thing; it comes packaged only in human containers.

There are many aspects of Dartmouth's purpose we might usefully inquire into as we prepare to commit a year of life to her aims and work. Since I shall soon again be elaborating one aspect of the matter with the seniors in Great Issues and touching another with the freshmen in the new introductory course, I propose this morning to focus on the sentinel of Dartmouth's purpose - the liberating arts.

IF the liberal arts have a meaning and utility of their own, Dartmouth presumably has a purpose which sets it apart from other types of educational enterprise. In probing this purpose it is worth noting that Dartmouth's life-long commitment to the primacy of undergraduate education, the central tenet of the historic American college, also sets her apart in climate, emphasis and, in some measure, in purpose from those vastly complex organisms we call universities.

There is another factor in the character of the College as she stands today that has a particular pertinence to the mission of the liberal arts. Dartmouth is not merely a contemporary organization of educational activity; it is an institution with foundations deep in the soil of American experience. We can say of her as Mallet said of Oxford: "Through all the changes, greater than the traditions gathered round her, wiser than the prejudices which she has outgrown...." This institutional quality in a college, like a coral harbor, builds up year by year, generation by generation crisis by crisis, benefaction by benefaction, dedicated man by dedicated man, until out of its own accumulation of experienced truth a sanctuary arises where the meaning and beauty of other times and climes may say their say to ours and be heard.

It is this institutional quality, with its footing deep in the meaning of the human heritage, that qualifies the College to be one of the main channels by which mankind's past ceaselessly passes through the present to become the future. And this brings us close, I believe, to the first of two reasons why the liberal arts can be counted on when it comes to the business of growing better men: I have in mind, first, that as the chromosomes of civilization, the liberal arts bring the best of the past to the service of the present and, second, that out of their ever-renewing hybrid vigor they liberate the best in a man into an expanding future.

Individually by our every thought and act we create the present by wagering our past on the future. This is true of the artist's poised brush, the uplifted sword, the hesitant pen of statesmen and the undergraduate's willingness to try anything once. The point is that out of such experiences as we've had each of us is ceaselessly placing personal wagers of judgment on what we think or assume or hope will be the better choice in a necktie, a fraternity, a course, a job, a wife, a foreign policy, and in the net of it all - a life.

Leaving aside certain psychopathologies, most of us, at least most of the time, are not looking for suicidal, self-defeating choices. We survive and prosper by seeking "best bets" for our personal purposes and more often than not we learn that

satisfactions in the human race run true to what horsemen call "form." In a most profound sense, the creations of beauty, the disciplines of truth and the humanities of life which come down to us as the liberal arts are simply the "best bets" the ages have been able to pass along to those of us in every generation who by God's grace are free to enjoy - yea, even to love - the experience of having our own entry in the human race.

Important and reassuring as it surely is that life's best teacher, experience, vouches for the liberal arts as the richest repository of earthly understanding and joy, I believe we do only very partial justice to our case if we rest it primarily on this passive view of the liberal arts as being merely arts appropriate to a free man. This may have been an adequate view of the matter in societies where the destiny of a man in freedom, or in slavery, or in animal-like drudgery, was largely determined by the chance of birth. But that day is gone in our land and it is a day on which the sun will surely set in every land where the idea of human justice and freedom is known even to one as it must some day be known to everyone.

In a free land the never-ending frontier of freedom's forward thrust is each man's mind. I suggest to you, and I avow for myself, that in our American society it behooves institutions of the liberal learning to take a dynamic view of their mission. Ours is the task to free as well as to nourish men's minds. This is why, as I have sought to understand the nature of Dartmouth's obligation to human society, I have come increasingly to think of our commitment of purpose as being to the liberating arts rather than just the liberal arts. It is the active, liberating quality of these arts, I believe, that makes them the "best bet" for Dartmouth's purposes.

ANY liberation means a conflict of counter values and forces whether the liberating be of an occupied nation or of an unoccupied mind - the only vacuum, incidentally, not abhorred by nature. Liberation in either sense involves valuing a thing not had and wanting it sufficiently to make the necessary disenthralling effort, even to the point of a struggle. The liberal arts become the liberating arts when taught, learned and practiced as they were created, as the witness of a man by personal struggle pressing toward his richest earthly destiny. Is not this the story of that hard-won discipline of the free mind that in one form of understanding or another we call science? Is it not the essence of creation in the arts and of the efforts of one man to tell the tale of other men meaningfully and beautifully?

If the liberal arts are these things, they are the product of the struggle, man by man, for the liberation of man's mind and spirit; as the product of such a struggle, their beckoning example when sensed through the shared experience of good teaching cannot fail to kindle in men such as are gathered here those inner desires which, once truly lighted, carry forward a man's education almost in spite of himself.

And there is yet another dynamic value in these arts that advances both the teaching and learning aspects of the educational process. The liberating arts, by their nature, are case studies in comparison and choice. Every good and every excellence has a history of many lesser alternatives.

Imaginatively taught and pursued, the liberal arts present choices ranging from the largest philosophic issues of wisdom and wrongdoing, through the dilemmas of statecraft, the hypotheses and many wrong ways of science to the most delicate variants of taste and style in expression and selection in all art forms. Few things are more basically liberating than the conscious exercise of a choice. A man is known best by his choices. I find that as I work my way further and further into the mysteries of education, I place an ever higher value on the growth in a student of sensitivity to comparative data and his growing awareness of the opportunities of choice. We may fairly ask, could any field other than the liberal arts yield as broad and as significant an introduction to life's comparisons and choices; could any other provide a more vital classroom experience for the development of men who are free not primarily because of birth, but because they have learned to use their birthright to choose a way of life?

A final word — from what enslavement do we seek liberation? I am sure each society, each time, and each man must answer this question individually. Any imposed answer is itself a denial of the worth of the aspiration to be free. And yet, let us candidly acknowledge that this faith in freedom and in the vital role of choice in education is itself a form of commitment which, in some measure, limits as it guides our efforts. As such, I suppose it is one of those "theological" starting points every man uses in some form for the purpose of getting a purchase on the universe. It is enough for this occasion to affirm our awareness that even a liberating education uses purchase points which for others may seem enthrallments of error. Perhaps the best we can say for this particular starting point is that in all the years ahead it invites, indeed it has no alternative but to invite, your honest examination of its validity.

When one addresses himself to the theme of liberation on the large canvas of our time, he ultimately finds that regardless of contemporary figures and forms he is sketching an ancient story. Men have invented many ways to do the devil's work and it sometimes takes a little while for a society to see through the most recent contraptions for creating hell on earth, but see through them we always have and in this respect the outlook at the moment is pretty good. It no longer requires either great daring or perspicacity to spot the common blight of mind and spirit inherent in the brutish and conspiratorial devices of communism and fascism, and, in our domestic life, processes of fairness and principles of decency have happily escaped becoming partisan issues. Even though the course ahead is dim and rugged, we can say today, as a strong America has finally been able to say in other periods of stress and crisis, we know whereof are the ways of enslavement and the ways of freedom. That, gentlemen, is a great deal either for a nation or for a man.

The motto of the State of New Hampshire reads: "Live Free or Die," and as you today go forward in the liberating arts I remind you that for us those words are not merely a political admonition; they are also a statement of fact - "Live Free or Die" is the law of intellectual life.

And now, men of Dartmouth, as I have said on this occasion before, as members of the College you have three different but closely intertwined roles to play:—

First, you are citizens of a community and are expected to act as such.

Second, you are the stuff of an institution and what you are it will be.

Thirdly, your business here is learning and that is up to you.

We'll be with you all the way, and "Good Luck!"

Part of the freshman class, in the Webster Hall balcony, at Convocation

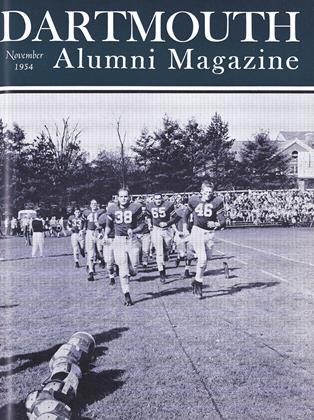

ANOTHER PRESIDENTIAL ADDRESS shortly after Convocation was delivered byPresident Dickey on Dartmouth Night, October I. Shown with him on the steps of Dart-mouth Hall are (left) Sidney C. Hayward '26, Secretary of the College, and (right) CoachTuss McLaughry and Lou Turner '55, captain of the football team.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureDOCTORS, ESKIMOS and DOGS

November 1954 By DR. ERWIN C. MILLER '20 -

Feature

FeatureA Backward Glance at the Humanities

November 1954 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

November 1954 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, RICHARD P. WHITE -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

November 1954 By G.H. CASSELS-SMITH '55 -

Article

ArticleA Roster of Dartmouth Alumni Clubs

November 1954 -

Article

ArticleFootball

November 1954 By CLIFF JORDAN '45

Features

-

Cover Story

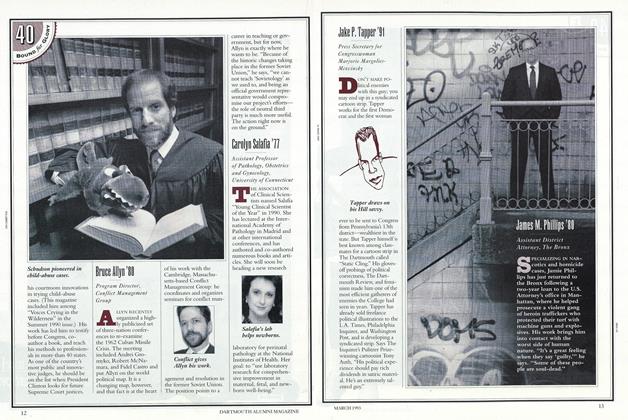

Cover StoryJames M. Phillips '80

March 1993 -

Cover Story

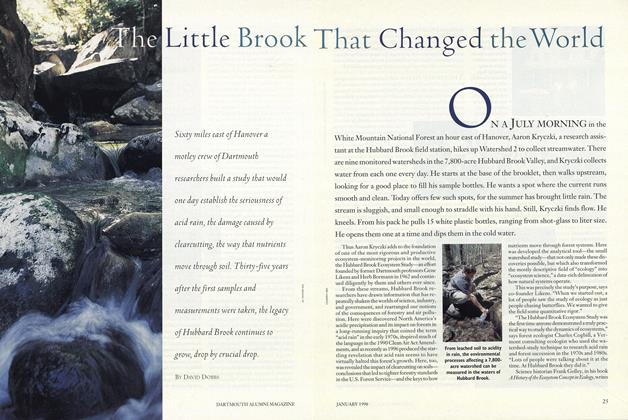

Cover StoryThe Little Brook That Changed the World

JANUARY 1998 By David Dobbs -

Feature

FeatureAn Open Door Policy

July/August 2006 By Irene M. Wielawski -

Feature

FeatureThe Dartmouth Story, A Narrative History Of The College Buildings, Peioke, and Legebds

June 1992 By Robert B. Graham '40 -

FEATURE

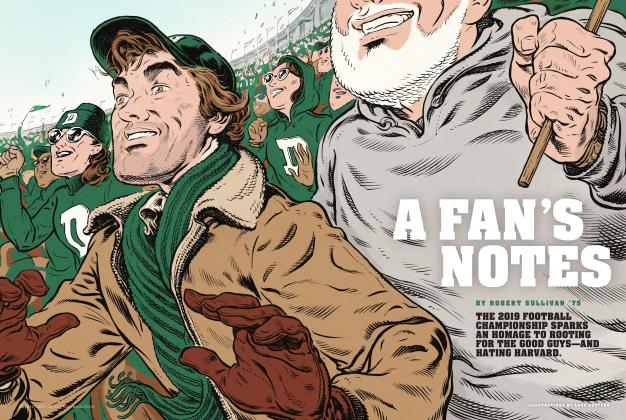

FEATUREA Fan’s Notes

MARCH | APRIL 2020 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75 -

Feature

FeatureOpening; Assembly

October 1951 By THE HONORABLE LEWIS W. DOUGLAS