The Imprint Society last spring issued inhandsome format The Poetry of Robert Frost, reprinting the edition originallyprepared in 1969 for Holt, Rinehart andWinston Inc. by E. C. Lathem, Librarianof the College. In this article, adaptedfrom his introduction to the Imprint Societypublication. Mr. Lathem treats ofvarious considerations associated with aneditorial assignment which grew out ofFrost's having himself sought his friend'sassistance with textual aspects of a comprehensivevolume the poet was planningjust prior to his death.

Following publication early in 1962 of In the Clearing, Robert Frost actively began considering the preparation of a new major collection of his verse, it having been some thirteen years since the appearance of his Complete Poems in 1949. It was clear to him that such a book would be constituted simply by adding the contents of In the Clearing to that of Complete Poems, and he resolved, too, the matter of the title to be used. He had never, he indicated, really been happy with the designation of the 1949 volume, which was by no means a complete gathering even at the time of its issuance, and it had, of course, inevitably become less complete with each new poem he wrote. Would not, he asked, with evident conviction as to its appropriateness, just The Poetry ofRobert Frost be best?

When Mr. Frost's death in January 1963 prevented his personally bringing the projected collection into being, the responsibility for doing so devolved upon his publishers and estate—the two being effectively joined under the poet's will, wherein he had named his friend who headed the firm of Holt, Rinehart and Winston to be his estate's sole executor and trustee.

From the outset several basic requirements for the book were obvious to those concerned with its planning. First, it must maintain the tradition of typographic excellence so long associated with Frost volumes. Happily, the accomplishment of this was fully assured by the agreement of Rudolph Ruzicka, internationally celebrated typographer and dean of America's graphic artists, to serve as designer.

Secondly, although in all of Holt's previous comprehensive editions of Robert Frost's poetry the scheme followed had been to accord a new page for the opening of each poem, this would now manifestly be unfeasible, for to have followed the Complete Poems format and to have added the pages necessary to accommodate the poems of In the Clearing, plus an index and slightly enlarged front matter, would have meant producing a book of well over seven hundred and fifty pages-undesirable in terms of both bulk and cost. (Actually, ample precedent existed, if precedent were required, of the author's having himself sanctioned his poems' being "run-on" in their publication. Several editions during his lifetime had embodied that feature. An attempted assessment, moreover, of the reaction of readers seemed to suggest that those who might feel that a two-line poem, for instance, on an otherwise blank page could have positive aesthetic force and significance were counterbalanced by other persons who firmly held that such was an awkward, wasteful, even ridiculous arrangement.)

A third fundamental conclusion was that there would be no critical introduction, nor would there be included Mr. Frost's celebrated essay "The Figure a Poem Makes," which had previously been used as a preface in several editions but which was by now readily available in the volume entitled SelectedProse of Robert Frost (New York, 1966). Similarly, in deference to Frost's distaste for them, interpretive notes were to be avoided. (The poet, in such connection, once quipped to an audience, "I'm afraid somebody'll have to write a footnote on that for me sometime, and I'll turn over in my grave if they do—I'll start revolving in my grave.") But it was felt that scholars, particularly, might value the availability of certain bibliographical information, and data on textual variations among the principal printed versions of the poetry.

The desire of the Frost Estate was for an edition that would serve both general readers and scholarly users. Although upon but casual consideration it might not seem that the needs of the two groups should be markedly dissimi lar, it was in fact found that circumstances of past publication and Frosts attitude toward his text were such that least the general reader would Oftentimes be helpfully served by some degree of editorial attention to the The decision was made, therefore, that this new collection, planned for publication in 1969, would be an edited one (hardly an unparalleled thing since edited posthumous collects' of other 20th Century poets exist, of course—including, for example, the recent Complete Poems of Walter de la Mare). The volume would, however, give within its notes section precise indication of all textual emendations by the editor. Thus, the desired objective could be attained of editorially enhancing textual clarity, while at the same time flagging every such change, so that scholars and others could readily know just which readings reflected editor's alterations.

Mr. Frost was, in many ways, a very inconsistent person—as Emerson proclaims great souls are wont to be. (It was, withal, one of the myriad fascinating aspects of his personality.) In some respects he cared a great deal about fine points of textual detail; in others, he was indifferent, if not actually perverse or cavalier, regarding them. His letters to his publishers and printers echo over and again the hope that his text would emerge, in book after book, as correct as possible. Yet he felt uneasy about, and shrank from, the responsibility of accomplishing that end himself. "I like an exact text as much as anybody," he wrote in 1930, while preparing his Collected Poems for the press, "but I should hate to have it left too much to me to achieve one. I reread my own poems, , when I have to, with a kind of shrinking eye that doesnt see very well. I doubt if it's inattention I suffer from. It may be love-blindness." And to another correspondent, who queried him, after the 1930 edition had appeared, about evident deficiencies of punctuation therein, he replied disarmingly: "... I indulge a sort of indifference to punctuation. I dont mean despise it. I value it. But I seem rather willing to let other people look after it for me."

Although, by and large, Frost did not actually relish having individuals challenge him regarding the punctuation of his verse, any more than he appreciated being questioned about substantive element of the poems, he sometimes did respond positively and appreciatively to corrective inquiry. Prof. George F. whicher of Amherst College entertainingly told, many years ago, of such an instance: "When 'The White-tailed Hornet' appeared in the Yale Review, my wife and I were absurdly perplexed by a line which then read:

To err is human, not to animal.

Was to a misprint for tool Had an essential word been omitted? Could toanimal conceivably be taken as an infinitive? The simple explanation eluded us as the obvious sometimes will, but that night my wife woke up from a sound sleep repeating the line with an intonation that cleared up the difficulty. We laughed with Frost over how we had been stumped, and for the sake of other dunderheads he printed the line in A Further Range:

To err is human, not to, animal.

If there can be," the professor concluded his anecdote, "Halley's comet, why not Whicher's comma—or in this case, Mrs. Whicher's, since she suggested gested it? All book-gazers are hereby notified."

In somewhat like manner, the present editor a decade and a half ago, in doing a special separate edition of the poem "New Hampshire," had occasion to make a number of textual queries of Mr. Frost, including one in a passage which within the copy-text (CompletePoems) read:

'You hear those hound-dogs sing on Moosilauke?

Well they remind me of the hue and cry

We've heard against the Mid-Victorians

In the second line as given, "Well" is apparently an adverb, descriptive of the manner in which or the degree to which the dogs remind the speaker of the hue and cry that has been raised—a grammatical construction equivalent to the second line of "The Vantage Point":

Well I know where to hie me—in the dawn, or the twelfth line of "The Demiurge's Laugh":

And well I knew what the Demon meant.

In fact, this was not the poet's intended sense at all, as might possibly be guessed through assessing the tone of the dialogue itself, but as could definitely be known by hearing Mr. Frost read the dialogue itself, but as could definiteinterjection, and it decidedly requires a comma to make plain that it is to be read as such. The author, on having his attention called to the matter, after more than thirty years of its standing otherwise in book upon book, promptly indicated that the change should be made:

Well, they remind me of the hue and cry

We've heard against the Mid-Victorians

When Mr. Frost talked about preparing the volume that was to be The Poetry of Robert Frost, one of the things foremost in his mind was a desire to comb out any British spellings which might still exist within the text of his first two books and which ought to be replaced with American forms. In the event, this proved to be an area of no problem at all, and corrections in orthography were associated more with other things. Proper names had been a minor bogey in the past. (Vilhjalmur Stefansson was for years, prior to ultimate correction, cited as "Steffanson," and Eugene O'Neill became "O'Neil" in the early printings of Complete Poems.) For the new book, "Hackluyt" was corrected to "Hakluyt" in the subtitle of "The Discovery of the Madeiras," and the reading "Georges Bank" (an area of ocean shelf providing excellent fishing grounds off the New England coast) was restored to the poem entitled "The Flower Boat," in place of the corruption "George's bank" which had badly obscured the reference. Also, the spelling of the orchid genus "Cypripedium" was changed from "Cyprepedium," even though the incorrect spelling was present in dialogue, on the grounds that there could be no difference in the word's pronunciation ("Langshang" on the other hand, although wrong, was not altered within its context of dialogue to "Langshan" since the two word-endings are quite differently said). Another phase of editorial attention to spellings involved normalizing such variants as "dye stuff" of A FurtherRange and "dyestuff" of In the Clearing, "meter" and "metre," "offense' and "offence," "ax" and "axe," "shan't" and "sha'n't."

Diverse spellings and irregularity of practice in punctuation are not, of course, apt to render text unintelligible, but they can distract, puzzle, and indeed annoy readers, undesirably intruding upon an assimilation of what the author has wished to communicate. A reader will most readily grasp the meaning of text in which spelling and punctuation are consistently styled. Since Robert Frost's first and last books were published nearly half a century apart, it seemed desirable to have as one of the objectives of the projected 1969 edition the attainment of a reasonable consistency in the styling of both spelling and punctuation—to have this styling represent usage at the close of Mr. Frost's career. This involved eliminating, for example, the heavy employment of hyphens to form words that in current usage would normally appear as either single or separate words. Although, obviously, there was need to exercise care to avoid altering hyphenization where it was really significant from the standpoint of sense or some feature of the poet's deliberate artistic intent, it would be hard to defend, on either practical or aesthetic grounds, that whereas "childlike" was satisfactory as employed in the copytext, there was reason to retain hyphens in such words as "star-like" or "business-like" or the rather absurd "unshiplike." And it is questionable also, to cite one further example, that it is helpful to readers to perpetuate the hyphenated form in the following passage from "Birches":

[...] when Truth broke in With all her matter-of-fact [...]

Here the term hyphenated is surely akin to that which appears in a line from "On the Heart's Beginning to Cloud the Mind" which in the copy-text reads:

Matter of fact has made them brave.

and not to that of the term as adverbially used in this passage in the copy-text's version of "One More Brevity":

In spite of the way his tail had smacked My floor so hard and matter-of-fact.

Similarly, with respect to commas, the line from "Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening" which the copy-text carries as:

His house is in the village though:

is perfectly intelligible as it stands, and it could be passed over just as it is, without the editorial insertion of a comma before "though" in this adverbial element. Yet to emend the line to:

His house is in the village, though; does seem in order, not out of deference to any rules, but because the comma's absence is divergent from a style pattern the reader has elsewhere encountered within the copy-text volume, in lines of similar construction such as these:

It's seldom I get down except for meals, though.

That's always the way with the blue. berries, though:

You can see what is troubling Granny, though.

I tell them they can't get me through the door, though:

Bless you, it's all expense, though.[...]

This is not sorrow, though; [...]

Unfortunately all of one kind, though

Therefore, the absence of a comma before "though" in the "Stopping by Woods..." line would be a difference which might claim the reader's consciousness, if only vaguely or momen- tarily so, distracting him from the text.

In this same poem another editorial consideration presents itself in a line which in the copy-text reads:

The woods are lovely, dark and deep [...]

As punctuated, "dark and deep" may be taken as in apposition to "lovely," defining the quality or character of the woods' loveliness. Or, alternatively, it is at least suggested that a pause in reading is intended after "lovely"—and that these are not simply adjectives given in series, which could be punctuated "lovely, dark, and deep." However, investigation reveals that in what appears to be the first-draft manuscript of the poem, Mr. Frost wrote the line:

The woods are lovely dark and deep and such utter lack of punctuation would seem to suggest he intended all three adjectives to have equal weight or stress. This supposition is further supported by evidence of the first appearance of the poem in a magazine, prior to book publication. There the phrase is exactly as it is in the apparent first draft, with no commas at all: "lovely dark and deep." (This unorthodox practice of wholly omitting punctuation for coordinate words in series is something the poet indulged in in his letters, and occasionally even in his books.) But conclusive evidence regarding the manner in which the line should be read (and, accordingly, how it should be punctuated) is provided by the manner in which the poet himself, in fact, said the line. Fortunately, there is in this respect no need to rely on memory, for literally scores of voice recordings exist of Frost saying his poems. Over and over again he is heard to give the three adjectives approximately equal stress, with no vocal suggestion that punctuation other than:

The woods are lovely, dark, and deep [...]

would be appropriate.

It is highly significant that with Robert Frost an editor undertake textual criticism has, in a fashion and to a degree that has doubtless never before obtained with regard to one of our major poets, an opportunity to draw not just upon manuscript and printed sources, but also upon a vast body of oral evidence as well.

Recordings that preserve Frost's own manner of saying his poems can frequently be used to remove ambiguity or bafflement arising from the poet's indifference to punctuation. Often, as has been suggested, absence or irregularity of punctuation is not so much an absolute difficulty as it is merely a deterrent to immediate comprehension. The following are a few examples of lines in which the commas have been supplied by the present editor, but which unpunctuated would be potentially troublesome:

A bead of silver water more on less, Strung on your hair, won't hurt your summer looks.

Though as for that, the passing there Had worn them really about the same [...]

"But why, when no one wants you to, go on?

As far as I can see, this autumn haze

Certain areas of editorial concern in preparing The Poetry of Rob-ert Frost have related to problems arising more from prior typographical, than literary, styling—or the absence thereof. In the matter of quote marks, for example, Complete Poems, one of the two copy-texts for this edition, uses single quotes for the opening of quotations and double quotes for quotations within quotations. Some readers in observing this have assumed it to be an extension of British practice imposed upon Mr. Frost's first two books when initially published in London in 1913 and 1914. Actually, although A BoysWill did follow such form, North ofBoston from its initial appearance used double quotes to begin quotations and single quotes for internal ones, and the advent of what has been mistakenly regarded as merely a continuation of English usage in quotation did not come into Frost's books on a compre- hensive basis until the 1930 edition of Collected Poems. It was therein merely a typographical refinement preferred by the book's designer (and subsequently regarded by him as not particularly successful experimentation), yet it had since 1930 been followed in all succeeding collected editions.

Other errors that sometimes in the st had crept into the selected and collected editions had resulted from a failure by proofreaders, including the poet himself, to realize that the provision of interlinear space (for various purposes of separation) had been omitted in the re-setting of poems. These mistakes often came about because in the printed versions used as copy-texts a line preceding the point at which extra interlinear space would normally have been desired had, as it happened, come at the bottom of a page. Thus, the printer, given no special instructions that additional line-spacing was required there, provided none, and if after the new setting of the poem the line in question did not again fall at the end of a page, the needed interlinear space was quite apt to be wanting. This result could be particularly damaging to dialogue. For instance, in the following passage early in the poem "Build Soil" the absence of spacing after the first line, which in the poem's original appearance in A Further Range was at the bottom of page eighty-six, makes it seem, as printed in collected and selected editions in 1939, 1946, 1949, 1955, and 1963, that all this text is uttered by one speaker, Tityrus:

I doubt if you're convinced the times are bad.

I keep my eye on Congress, Meliboeus. They're in the best position of us all To know if anything is very wrong.

I mean they could be trusted to give the alarm [...]

However, a careful (and, of course, disconcerting to a reader) analysis of the dialogue which immediately precedes this will reveal—as manuscript evidence sustains—the first line is not Tityrus's at all, but is spoken by the other character in the poem, Meliboeus.

The foregoing is suggestive of some of the considerations which confronted the editor in his preparation of the 1969 edition, The Poetry of RobertFrost, which was in 1971 issued anew by The Imprint Society. Working under the authority of those responsible for administering Mr. Frost's literary interests, he attempted to accomplish their established goal of bringing forth a volume having as great a degree of accuracy and clarity of text as possible-a purpose based on a recognition of the substantial lack of careful textual scrutiny which had characterized Frost editions in the past and, also, on the poet's known desire to have any new collection at this juncture subjected to a thorough review of its text. The editor's assigned task was to edit: to proceed with care, restraint, and convictionoperating within a scope of limited range, using restricted means, being neither inflexible nor yet erratic or casual in the exercise of critical attention and editorial treatment—and acting on the basis of having gathered from manuscript, printed, and oral sources as much textual evidence as possible (but very little of which, because of space limitations, could be reflected in the book's notes). Such was the aim and effort.

Had Mr. Frost lived to preside over the creation of this comprehensive volume, it would undoubtedly have had differences from the present book. It might have included a few new poems (as Complete Poems had done back in 1949). It possibly would have carried, too, an introductory essay by the poet. It almost surely would not have featured bibliographical notes or indication of variant readings. And clearly there would have been no need for the citing of emendations within it, since these would have been changes, whether verbal or punctuational, which the author could freely have made (as indeed he had in earlier editions) without any declaration whatsoever, while it has of course been proper for the editor to record minutely herein each and all of his alterations of any kind. It is hoped, however, that ThePoetry of Robert Frost, conservatively edited as a book for both the general reader and the scholar, and as an interim provision against the time when a variorum or definitive edition is prepared, will prove to be both a useful and a convenient volume.

The editor had in his work the advantage of, and is most grateful for, the full cooperation and counsel of the Robert Frost Estate, as well as the assistance of several individuals having special qualification to advise him on matters associated with the textual review of Mr. Frost's verse. For this he continues to feel deep obligation.

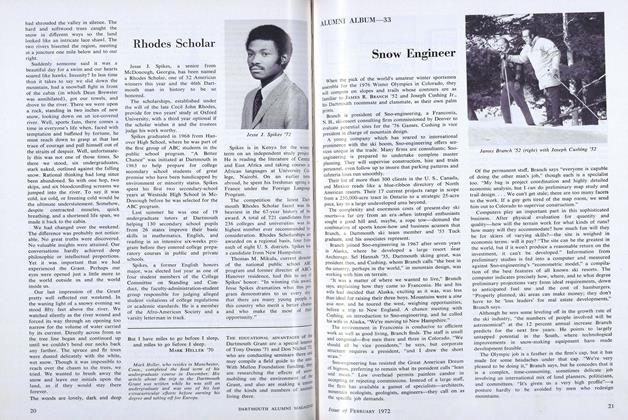

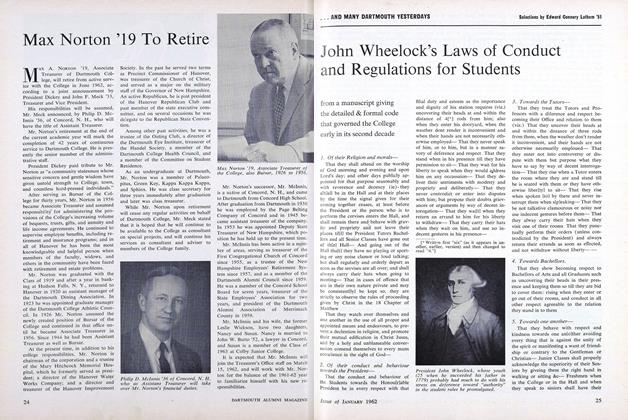

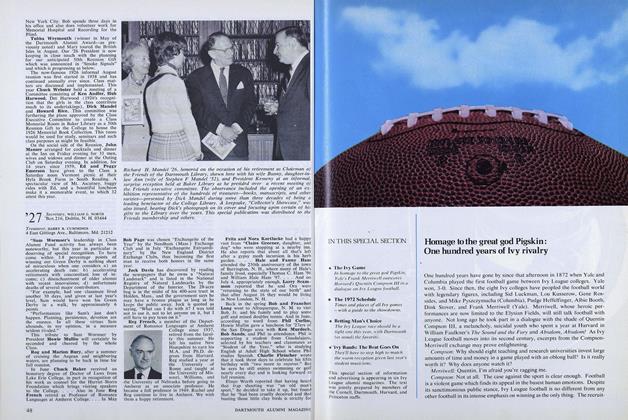

The Robert Frost portrait above was done inlow relief by Rudolph Ruzicka of Hanoveras the frontispiece for the Imprint Societyedition.

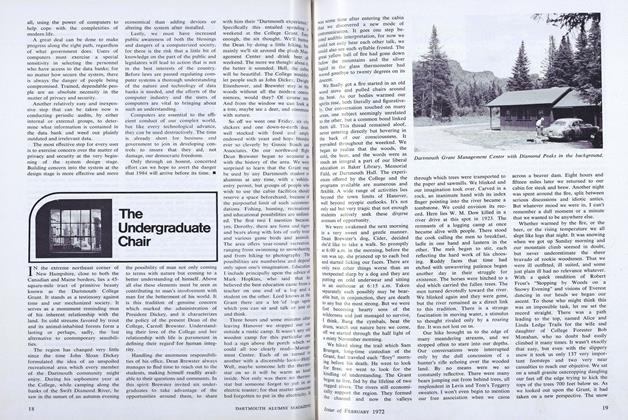

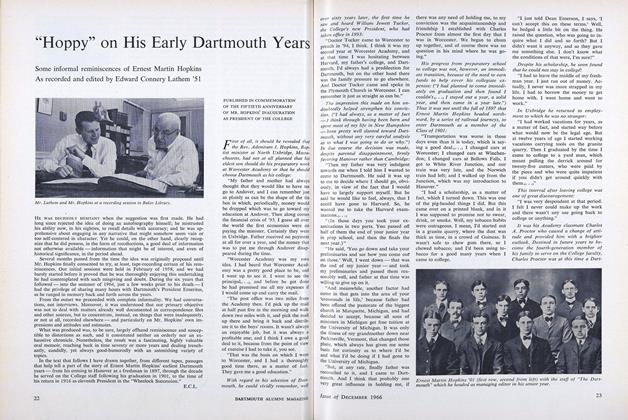

Mr. Lathem, editor of "The Poetry of Robert Frost," shown with Frost in April1962, nine months before the poet's death, on the occasion of the opening of theRobert Frost Room in Baker Memorial Library at Dartmouth.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Growing Threat to Privacy Posed by Computer Data Banks

February 1972 By ROBERT P. HENDERSON '53 -

Feature

FeatureTrustees Meet with Alumni Council

February 1972 -

Feature

FeatureSymphony Conductor

February 1972 -

Feature

FeatureExecutive Exporter

February 1972 -

Feature

FeatureSnow Engineer

February 1972 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

February 1972 By MARK HELLER '70

EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51

-

Feature

FeatureTHE MOCK-DUEL MURDER

April 1956 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51 -

Feature

FeatureDARTMOUTH and DARTMOUTH

DECEMBER 1958 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51 -

Feature

Feature"As I Remember..."

January 1960 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51 -

Feature

FeatureJohn Wheelock's Laws of Conduct and Regulations for Students

January 1962 By Edward Connery Lathem '51 -

Article

ArticleApril 1865: Jubilation and Grief

April 1962 By Edward Connery Lathem '51 -

Feature

Feature"Hoppy" on His Early Dartmouth Years

DECEMBER 1966 By Edward Connery Lathem '51

Features

-

Feature

FeatureHomage to the great god Pigskin: One hundred years of Ivy rivalry

OCTOBER 1972 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

Nov/Dec 2005 -

Feature

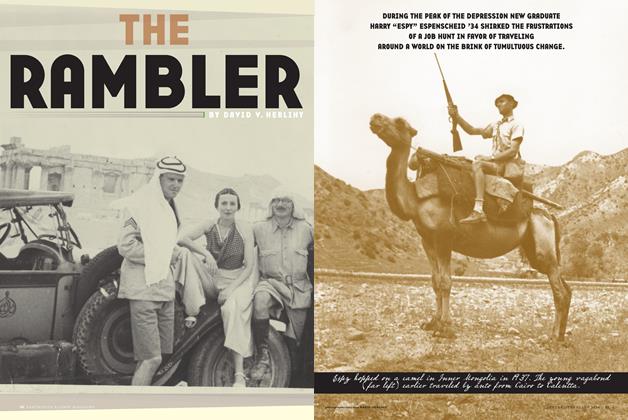

FeatureThe Rambler

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2014 By DAVID V. HERLIHY -

Feature

FeatureArt Imitates Life

MAY | JUNE 2017 By LISA FURLONG -

Feature

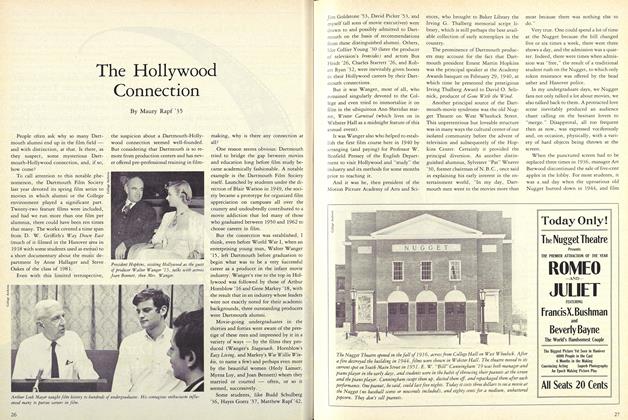

FeatureThe Hollywood Connection

November 1982 By Maury Rapf '35 -

Feature

FeatureA Billion Dollars

NOVEMBER 1996 By Rebecca Bailey