Praise for Braden

TO THE EDITOR:

Braden's account of the reforming of California teacher training understates his own participation. His willingness to take on the educational Establishment, as entrenched here as anywhere, was joined to unwearying persistence. He was indifferent to dead cats hurled from high places and low, ducking some and throwing back others.

The victory is, as Braden says, precarious. We cannot assume that the educational Establishment has given up. As long as he remains on the State Board, however, it appears unlikely that Chinese degrees in educationist topics will again be accepted as substitutes for knowledge.

I was especially glad to see Braden's piece in the pages of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE. I hope it establishes a precedent. It is fitting that we should be given some measure of the Trustees of the College, especially their outlook on educational matters. As this letter is written, the Regents - i.e., the Trustees - of the University of California are displaying a remarkable ignorance about the university's purposes and functions. The result of this ignorance is likely to be the demoralization of the institution for years to come. The Trustees of private universities and colleges, one hopes, are more conversant than public Trustees with the aims and methods of higher education, and less subject to pressures from the wealthy and secure and other sentinels of the status quo.

I hope, in short, that we may hear much more from our own Trustees on educational questions as timely and pertinent as the one Braden discusses.

Santa Barbara, Calif.

"Outright Intellectual Snobbery"

TO THE EDITOR:

Thomas Braden's article entitled "Our Battle to Reform the Education of Teachers" made interesting reading but could hardly be praised for anything else.

For one thing he sets forth four rules for "getting ahead in education," applying them by implication to an obvious demagogue in a position of leadership in California's department of education; but then he proceeds to qualify himself under his own rules for the same type of demagoguery. Instead of showing righteous anger at things like teachers, primers about Dick and Jane, sight reading, and John Dewey, Braden shows his righteous anger at anybody having an Ed.D. degree or qualifying under his implied definition of an "educationist." He identifies his actions to reform teacher certification with learning, concluding by implication that all who have disagreed with him cannot possibly be equally identified. And then he is sad because his own children - and thus all children - have received some apparently meaningless report cards in school.

He uses half-truths, takes quotations out of context, draws conclusions from isolated illustrations of his chosen points, and generally fulfills all of the qualifications for the demagogue he is so much against.

Further, Braden's criticism of the "doctors of education" and professional educators and his allusion to them as "educationists" smacks of outright intellectual snobbery. It is easy enough to find handy illustrations of incompetence within most professional groups (legal, medical, educational, etc.), so to pick out juicy morsels of ridiculous procedure by certain people in education and thereby damn the whole lot of them is clearly illogical and smelling of egotism.

Teacher education needs reform, not only in California but also throughout the nation, as Dr. Conant has so well indicated. California years ago started moving in this direction and was making significant progress when Braden came on to the State Board of Education. And as he so rightly indicates, change for the better was being hampered by certain vested interests. The Fisher Bill, however, coming out of the California Senate, gave the movement an emotionally conceived but final legislative mandate, and the State Board of Education has been doing a forthright job of implementing the law; but it is intellectual blindness for anyone to infer that professional educators have not been responsible for making the change practical and feasible.

It is good that men like Braden see visions of what should be, but it is well that they do not invest themselves with halos and forget that there are those who always bring their visions down to earth and make them suitable for use.

Chowchilla, Calif.

Regarding "Vanishing Absolutes"

TO THE EDITOR:

Re: Vanishing Absolutes by Professor Richard P. Unsworth

If I read Professor Unsworth correctly, he proposes an ethic of service to replace the principle of "Thou shalt not," which is often inapplicable in a complex, and institutionally structured, society.

With this I agree. An ethic of service extends what were formerly optional actions into responsibilities. At the same time it subsumes the negative and somewhat legalistic moral axioms of the Old Testament

within the implied concept of the outer-directed man. However, I think that the service gener- alization is as inadequate for coping with day-to-day business decisions as the "Thou shalt not (steal)" principle. I will use one of Professor Unsworth's businessman examples to make the point, although I feel neither case forces the issue of ethical choice within a multi-variable fact situation.

(If the automobile manufacturing official planned his little coup, then he clearly steals, though the theft attains sophistication through a series of transactions, which, singly, are innocuous enough. The ballpoint pen maker with a potential order is probably not confronted with a serious moral dilemma because he may lower his price to the old customer. Not only is this ethical, but most likely the best all-around business decision, since it increases volume substantially and probably preserves the good will and competitive position of the old customer. If the old customer's business contracts, so will his orders.)

Assuming, for the sake of discussion, that the interest of the ballpoint shareholders is advanced by maintaining the high price (profit margin) to the old customer, while reducing the price to the new customer, what application does the "thou shalt not steal" principle have to the executive's decision on accepting the new business? Prob- ably little. Though he cannot avoid "stealing" from either the shareholders or the old customer, he is contractually bound as an employee to act in the interest of the company owner(s), i.e. the shareholders. Again, what impact would application of the service principle have to the executive's decision? Again little. The service of the old customer is the disservice of the shareholders and vice versa. Contractual obligations supersede sympathy for the old customer.

I suppose utilization of the service principle in this circumstance would involve vectoring the flow of consequences in some way to yield an optimum benefit-detriment quantum. But here, as in many circumstances, society has pre-decided the ethical issue. The executive who acts against the interest of the company owners commits a corporate rebellion.

If what I have said is an admittedly simplified, but rough approximation of the availability of ethical standards in a particular business situation, two inferences may be drawn. (1) Persons acting in an official capacity often have narrow ethical latitude because of legal obligation or antecedent commitments to the institution (s) they represent. (2) The ethical choice is moved back to the point at which the individual contemplates entering business or other institutions, thereby accepting or rejecting the non-availability of an ethical standard for future, inevitable situations. Acceptance or rejection of this condition, in turn, rests on his estimation of the value of the service he will provide as a manager of human resources and supplier of natural and/or induced desires.

Walpole, N. H.

"The Answers Are Very Definite"

TO THE EDITOR:

It was interesting to read Professor Unsworth's article on "Vanishing Absolutes." The questions he raised in regard to business seemed to me to be very superficial. He implies that there are no clearcut answers to the questions he raised, but the answers are very definite.

1. In regard to the ballpoint pen manufacturer, if he sold the same product to a second manufacturer at a slightly reduced price and didn't offer the first manufacturer the same price for the same volume, the Patman Act could be used against him, and he would be subject to a fine.

2. The automobile manufacturing concern situation he mentioned, of course, actually came up with Chrysler. As a result of it, Chrysler has a new president and the purchasing agent is no longer with the company.

I think there is no question that the standards of ethics are very definite in business. I think there is also no question that today, as in generations past, in many cases people may not live according to those standards.

The ethical principles under attack that he mentions are there, and they can be applied. Many people just don't have the courage to apply them. That, however, is no reason for throwing the principles overboard and adopting the philosophy of this article that nothing is right and nothing is wrong.

I submit that the forces that rule our lives are not so complex when you come to the basic principles by which men live. The real problem is finding men with courage to live according to principles that have been established over many thousands of years by many fine religions

Dallas, Texas

"Gutless Atmosphere"

TO THE EDITOR

Much sickening nonsense has exuded from many a campus, but never have I seen anything to compare with the address to the freshman class made by Dean Unsworth as reported in the December ALUMNI MAGAZINE.

Unsworth claims our ethical absolutes have vanished. He seeks to prove it by two examples which show all too clearly how far removed he is from the reality of daily life.

Unsworth says that "stealing" is no longer an absolute, that there are many gradations, most obsolete, and too difficult to wrestle with amid the complexities of modern life. Rubbish!

We quote: "Let's take a case, something simple like the Biblical commandment 'Thou shalt not steal.' Now you can do two things with that commandment, in order to make it work. You can say that in certain circumstances, stealing is permissible; or you can say that in certain circumstances, what would otherwise be called stealing is not really stealing."

To prove this, Rev. Unsworth offers the dilemma of a ballpoint pen manufacturer who has been selling for years to one fabricator at an established price. Then comes the chance to get another half million dollars per year if he will just sell the same product to another fabricator at a slightly reduce price. Ergo: the alternatives are to steal from the stockholders by NOT taking the new business, or steal from the old customer by accepting the new business.

Well, I have news for Rev. Unsworth! There is at least one other alternative which would be taken routinely by almost any ethical businessman without even thinking twice. The new business would be taken. The old customer would be called and told that the extra volume justified a new lower price to him. And no one is "stealing" from anybody!

The Reverend's second example is even less convincing. He offers an executive in an auto company who buys control of a parts supplier, inflates it with orders, and then wrecks it for his own personal profit. "Everything was very legal. No one rifled anyone else's pocket."

That is stealing, and would be so regarded by almost every business executive in any responsible position. I do not believe that the complexities of modern life justify our not thinking clearly about this "Absolute. I shrink in horror from Unsworth's suggestion that we should no longer concern our-selves about such "ethical absolutes": That we should take the easy way and salve our conscience by increased sensitivity to man.

Here we have exposed the fallacy of the extreme do-good attitude, seldom stated so precisely. One cannot struggle with the hard day-to-day decisions of ethics and philosophy. Just think kindly and sensitively of your fellow man, and you will be doing enough. What philosophical opium!

For some years I have been increasingly disgusted with the gutless atmosphere pervading Dartmouth. I have talked endlessly with many of the old professors who long ago saw all too clearly what was taking place. And I have obtained the Great Issues Lectures, searching in vain for the discussion of any really fundamental issue which might be open to controversy. All seems mush and pap.

But now, when freshmen are officially greeted with an address like Rev. Unsworth's, I have really had it, as far as Dartmouth is concerned. Believe me, it is a sad thing for an alumnus to view the sombre shell of a once great College.

Schenectady, N. Y.

Consternation Above

TO THE EDITOR:

A flying sorcerer reports that on that September day that the Reverend Richard P. Unsworth, Dean of the Tucker Foundation, gave his talk on vanishing absolutes to the freshmen of '68, the Reverend William Jewett Tucker, surrounded by a group of brother divines, was heard to repeat over and over, "O Temporal O Mores!" On the edge of the group Eleazar Wheelock muttered, "Mea vox quae clamavit in deserto muta est."

The sorcerer said that on his way out he asked the gatekeeper, "What's it all about? The boys seem all het up, but that lingo is before my time. What's it mean?"

"To you it would mean that Dr. Tucker does not like the way things are going down below. And the Reverend Eleazar is just speechless, that's all."

Not Enough Diversity

TO THE EDITOR:

Reading "The Undergraduate Chair" in the December ALUMNI MAGAZINE, I was impressed though not surprised by the information that "in the last eight presidential polls from 1920 to 1952 [Dartmouth] students had picked the Republican candidate in each case by margins of no less than 61 percent." I was not surprised because in 1932 when I was a sophomore Dartmouth students stayed with Hoover over Roosevelt by an overwhelming margin, although the nation as a whole repudiated the Republican Party and its policies by an electoral vote of 472 to 59. In the third year of the severest economic and financial depression this country has ever known the only solution clear to the Dartmouth student was "more of the same." Now that the term "mainstream" has been popularized, it would seem that no one was farther from the mainstream of

American thought and feeling than the student of that time.

This is not an anti-Republican diatribe, for I think it would have been just as unwholesome if the campus poll had elected only Democrats for four decades. Certainly one conclusion can be drawn, perhaps too obvious to repeat: that in spite of the College's efforts to achieve diversity in its freshman classes and its undoubted ability to attract brains and talent, one predominant quality persists through all time's changes, and that is wealth, and the attitudes and prejudices which wealth encourages and justifies. It would be just as one-sided in background and thought if all the students were the sons of laboring men. The sad thing is that the student body cannot be a more representative cross-section of all classes and traditions of American society.

Newport, R. I.

Culture in the Field House

TO THE EDITOR:

I would like to add my approval to Al Foley's recent article on the state of sloppy appearance of a "certain percentage of our current students."

As an alumnus with an admitted interest and concern for the whole student body, may I take this opportunity to single out a segment of our current undergraduate population which is a refreshing EXCEPTION to these "New Barbarians" — namely our Dartmouth Athletic teams.

I have had occasion to see many Dartmouth teams in civilian -dress during the last 25 years. The present crop is like the others — well groomed, conservatively dressed, and well-behaved. If these young men have achieved this degree of discipline, may I congratulate them and their coaches, who must be influencing these boys along the right lines.

In my humble opinion, perhaps Davis Field House is in truth more of a cultural center than some of our more impressive buildings on the campus.

Southbridge, Mass.

Against Safaris

TO THE EDITOR:

I recently came across one of your magazines containing the story of Dr. Lena's safari and the 49 trophies he so proudly brought down in Africa.

I thought they were trying to preserve the last bit of wildlife they have down there before it becomes extinct, and then they allow safaris like this. I just don't get it at all.

Well, all I can say is I hope he enjoyed himself killing off all those beautiful animals. But boy am I burned up, and I imagine other readers of this article are too.

Stratford, Conn.

One "L" Too Many

TO THE EDITOR:

I am sure that a lot of us who have heard Lew Stilwell's laugh, particularly in the Wigwam bull sessions, have caught the misspelling of his name on Page 29 of your December issue.

Brussels, Belgium

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

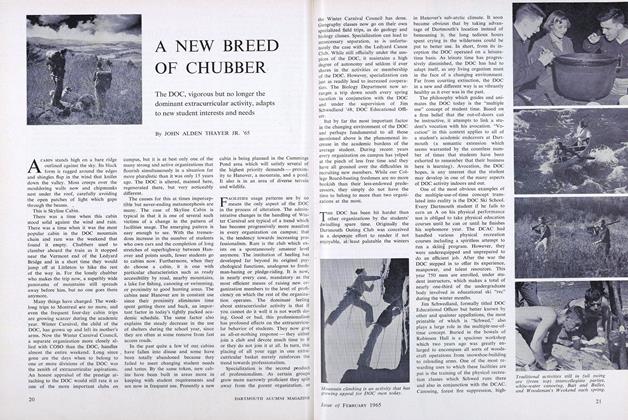

FeatureA NEW BREED OF CHUBBER

February 1965 By JOHN ALDEN THAYER JR. '65 -

Feature

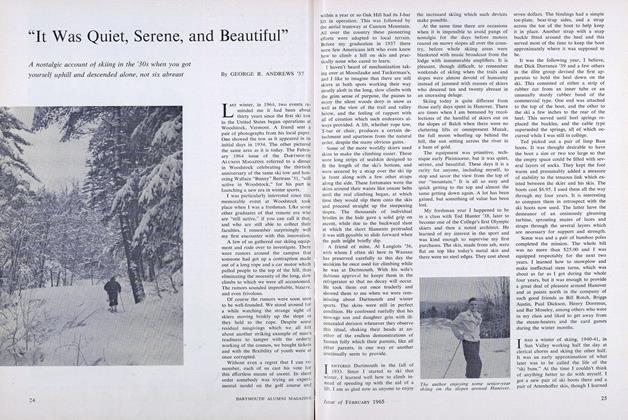

Feature"It Was Quiet, Serene, and Beautiful"

February 1965 By GEORGE R. ANDREWS '37 -

Feature

FeatureBusiness Still Draws Its Share of Graduates

February 1965 By ADDISON L. WINSHIP '42 -

Feature

FeatureFreshman-Sophomore Curriculum Revised

February 1965 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

February 1965 By BOB WILDAU '65 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth's Story Superbly Told

February 1965 By ALBERT I. DICKERSON '30