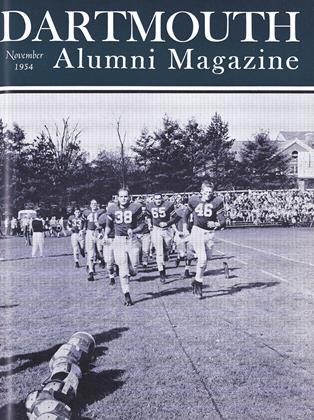

OUR seasons have gone haywire - what with a wintry summer and, as of this writing, a tepid albeit blustery autumn—and we can no longer trust the calendar. Even Aries the ram, tutelary genius of spring from the time of Hipparchus to that of Spud Bray, has, through the stodgy procession of the equinoxes, relinquished his vantage point to Pisces. Is it, then, overfantastic to look on the opening months of the college year as our own special vernal season, when academic nature springs to a rebirth and the young rams are rampant? Our thoughts turn annually to the very youngest of the flock: the little lambs, strangers in a world they never made.

Their path is smoothed with orientation, indoctrination, and various other -ations, and they are probably the last to think that they have problems. Cleareyed and trusting, they plunge into the curriculum, the tug-of-war, the Commons, and the D.0.C., many of them enduring, as single men in barracks, their first freedom from parental solicitude. See them on the streets, at games, in lecture halls, or on punched cards, and they are a conglomerate mass just starting the process of becoming a sentient unit in the alumni body. We hear knowledge caromed off the blackboards in a dozen different disciplines as we pass the open classroom windows along Dartmouth Row, where, indeed, if the weather held, an impecunious chela might squat on the turf and obtain adequate tuition without payment. Blobs of learning are being tossed to untrained seals, not yet sufficiently sophisticated either to applaud with their flippers or play My Country 'tis ofThee on the trumpet.

We would not imply an assembly line production of erudition or that the class is an amorphous blur before the instructor's eyes. Freshman math sessions disclose individual problems far beyond our poor power to add or subtract, and the social sciences start in- numerable private hares a-coursing. No doubt many a yearling first learns in language class that his high school inamorata has inaccurately been considered a femme fatale, and that he has suffered a fate somewhat better than death; and exposure to the Old Testament in English 1 is apt to bring to light both Fundamentalists who have kept careful count of the animals entering the ark, and youngsters who can incise Hebrew characters and accents on the board and explain the difficulties of translating an ancient tongue into a modern idiom.

The individual emerges most sharply, however, in the conference, the autobiographical theme, the fireside session. Religious doubts, lofty aspirations, social problems are the common lot of mankind, but it is frightening to have one's poor prescience deferred to by young natives who have not yet reached the mutilating stage of tribal initiation into the sophomore year. They consider themselves experts in Dickensian matters because they have seen OliverTwist, Great Expectations, and ThePickwick Papers in the films, but they cannot distinguish between Marilyn Monroe and Marilyn Miller. They are assured or bashful, knowing or knowledgeable, surly or winning, but miscellaneous as they may appear, we remind ourself that each one of them is a paragon in somebody's eyes and has probably left some homestead unaccustomedly quiet, with the order for milk delivery cut down and a loaf of bread impossible to use up before it spoils.

Fortunately, youth is hardy and will survive even the most bumbling of wellintentioned efforts. The College confidently passes to her sons such light as she has been vouchsafed, but many of her agents, while not openly advertising a lack of omniscience, would admit privately that " 'tis an awkward thing to play with souls, and matter enough to save one's own."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureDOCTORS, ESKIMOS and DOGS

November 1954 By DR. ERWIN C. MILLER '20 -

Feature

FeatureThe Liberating Arts

November 1954 -

Feature

FeatureA Backward Glance at the Humanities

November 1954 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

November 1954 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, RICHARD P. WHITE -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

November 1954 By G.H. CASSELS-SMITH '55 -

Article

ArticleA Roster of Dartmouth Alumni Clubs

November 1954

BILL McCARTER '19

-

Article

ArticleThe Hanover Scene

January 1953 By BILL McCARTER '19 -

Article

ArticleThe Hanover Scene

February 1953 By BILL McCARTER '19 -

Article

ArticleThe Hanover Scene

March 1955 By BILL McCARTER '19 -

Article

ArticleThe Hanover Scene

January 1957 By BILL McCARTER '19 -

Article

ArticleThe Hanover Scene

April 1957 By BILL McCARTER '19 -

Article

ArticleTHE HANOVER SCENE

OCTOBER 1958 By BILL MCCARTER '19