E.O.N. has cogitationes tempore doloris scriptas.

LAWRENCE PROFESSOR OF THE GREEK LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE

IN mid-September of 1913 I was walking up the valley from Interlaken to Lauterbrunnen, with a rucksack on my back and my destination mountains, mountains, and more mountains. To the right rose the steep rock walls on whose summit Mürren looked out over glaciers and the Jungfrau; to the left the Wengen Alps, where the path zig-zagged up over the Kleine Scheidegg and down to Grindelwald. It was cool in September that year but on this day the sun shone bright and warm from a cloudless sky, and as I walked steadily southward up the slightly rising road to Lauterbrunnen, my heart and mind and senses were full of poetry. Indeed, "Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive, but to be young was very Heaven!"

I had completed my undergraduate years, spent one year in a graduate school, and then set out from the "little world" of a New England city to the "great world" of Europe. Before beginning my trip in Switzerland I had studied German at a summer school in what was then the enchanting town of Freiburg im Breisgau, in preparation for further study of Greek and Latin at the University of Gottingen. There I was to hear the lectures of the almost mythical figures of Friedrich Leo, Busolt, and Wilhelm Meyer aus Speyer.

All this was in the future and, unlike Faust, I rejoiced in saying to the passing moment: "Verweile doch, du bist so schön!" As I went along a level stretch of road, I heard a carriage approaching from behind, drawn by two horses, judging by the sound of their feet, the feet of weary, despondent, disillusioned horses, drawing a hired conveyance occupied by tourists. On the front seat was the driver and on the rear an elderly gentleman and a middleaged lady, who, I learned later, was his daughter. As they drove past me, they suddenly stopped. I had not thumbed a ride, for in those days, glacier-swift compared with the tempo of our decade, the thumb was used in extracting plums from pies, not in solving transportation problems. The old gentleman, an Englishman, asked me if I should like to ride to Lauterbrunnen. I thanked him and replied that I preferred to walk. He, in spite of the reputed taciturnity of the English, apparently wanted to talk. He asked me where I came from, where I was going, and finally, what I planned to do as my life work. When I told him that I was preparing to teach, he quoted (and it was the first time, but not the last, that I heard it) Bernard Shaw's apothegm: "He who can, does. He who cannot, teaches."

Six years later, in 1919, on almost exactly the same day of September as that on which I had been walking from Interlaken to Lauterbrunnen, I arrived in Hanover. In the intervening years I had studied two semesters at Göttingen, taken my Ph.D. degree, and taught three years in a New England university. Through it all, I never forgot, in fact, I never have forgotten, the Mephistophelean barbs of Shaw's poisonous but purging arrow.

Unlike most colleges, perhaps, Dartmouth, in no small measure, is what it is because of where it is. The devotion of her students and of her graduates may be partially explained by the very beauty of this northern landscape, with its infinite variety of loveliness in summer, autumn, and winter. (De vere potius sileamus!) It was into this landscape, warmed by the lingering sun of late summer, that I arrived on that mid-September day. As I left the White River bus at the Inn and went in to get a room for the next few days, I was informed by the room-clerk: "You boys who are taking the entrance examinations can get your meals here but you will have to sleep in Hubbard Hall." This was a distinct blow to my self-esteem. I was almost thirty years old and, what was more, I was an assistant professor in Dartmouth College. I informed the young man of this latter fact and was given a room.

Hanover was even then suffering from its perennial affliction of housing shortage. I managed to find living quarters on Main Street on the second floor of a two-family wooden house which stood just opposite the entrance to Tuck Drive. It was a cold winter with over a hundred days of sleighing. There were no mechanical plows then, and the snow in the streets was packed down by drawing a ten-foot high and six- foot wide wooden roller through the town with a pair of horses. But then, so far as I know, no one on the faculty at that time owned an automobile.

21 North Main Street was an old house, the temperature not infrequently fell to 25 degrees below zero, and coal cost twenty dollars a ton. No amount of celebration seemed to keep one warm. The "Noble Experiment," in force at that time, made it impossible to apply heating agents internally. We thought of spring with a dogged will to believe, and in time the vernal equinox was just around the corner, was there, and with it the worst blizzard of the year and the cancelling of all classes for the day. This act, unprecedented in the history of the institution, brought forth from a well known local wit of the time: "Dartmouth, Mother of Men? Grandmother, I call it!" The almost frightening severity of the winter weather, however, was offset by the friendliness with which both Faculty and Administration welcomed the newcomer.

When I began teaching at Dartmouth in the fall of 1919, there were about two hundred Freshmen enrolled in the traditional Latin course: Livy, Terence, and Horace's Odes. This was no indication of a vital interest in classical studies. For one thing, the Class of 1923, then entering as Freshmen, was the largest class ever to come to Dartmouth up to that time. The unfortunate Freshman of those days had to choose between a course of study leading to an A.B. degree and one leading to a B.S. If he chose the former, he must elect Latin; if the latter, mathematics. Some who felt unsure of their preparation in Latin, but who feared mathematics, elected Greek. In the Twenties there were sometimes as many as fifty men enrolled in elementary Greek, forty in the second year course, and a goodly number going on to Greek tragedy and Plato. We even had a few majors in those days. Some men, in spite of the three-fold way to the degree, were unsuccessful. I remember a few students who repeated the same Latin course for four years and failed to pass in Senior year as handily as when they were Freshmen.

I feel I should say something of the impression the Dartmouth student made upon me compared with the students in the college where I had formerly taught. Dartmouth had not then become the truly national institution it is today. Its students, in general, did not come from the same social background nor from the same famous private schools as the students whom I had known. But I was immediately struck by the greater eagerness, willingness to work, and "desire to know," as Aristotle describes it, which characterized the Dartmouth student. There was nothing of the blasé, the "know it all," the super-sophisticated at Dartmouth. It soon was apparent that here was an exciting environment to teach in.

Added to the eagerness of the student body was a quality in the academic atmosphere, without which no teacher, and particularly no teacher of the humanities, can succeed in fulfilling his purpose. It is hard to find words for this, because in the neurotic age in which we are now living, all words appropriate to it are regarded with suspicion and fear. The words we used then were tolerance, liberalism, academic freedom. They are still good words; it is only fashions that have changed. In these days of malicious whispering men seem to fear that such qualities imperil their very survival. In the Twenties, however, they were assumed by the Faculty and guaranteed by the Administration. It is still true today, in fact, though we hear the words less frequently. It is sometimes said that liberalism is but the diguise worn by subversive agents. This may be true but it is not a valid argument against liberalism. Even the most unscrupulous salesman assumes the appearance of honesty; but that is no argument against honesty. Nor is it true, as is often said, that the liberal man is the indifferent man and that no one is liberal about what he ardently believes. For liberalism, the desire to think one's thoughts and to express them, is itself a passion in the mind of the effective teacher. Without this freedom education is impossible. I do not mean to imply that Dartmouth College stands alone in this. On the contrary, most educational institutions in the "free world" guarantee such freedom, but it must be won independently by each. It must be valiantly guarded, nourished by its own character, and cherished, lest, once it has been won, it wither through neglect and perish.

It is in part because of the guarantee of these freedoms that Dartmouth College is a great institution of teaching. That is what institutions at the collegiate level should always be. I have no quarrel with research, but I think one must distinguish between research which finds its way into print and that which nourishes and vitalizes the mind of the teacher. They are both good; they are both important. The inert mind, the unsearching mind, is intolerable in a teacher. There is the teacher of the microcosm and the teacher of the macrocosm. Both are necessary. New facts in the physical and natural sciences, the strange behavior of cum-clauses in Tacitus, or the discovery of new historical data are all significant. Too great absorption in microcosmic matters, however, confines the scholar to a cold and barren cell without windows. The duty of the teacher at the collegiate level is to open windows outwards upon the macrocosm - the great world. "The universe is one," cried Xenophanes of Colophon. Microcosmic matters belong at the graduate school level.

Furthermore, all collegiate teaching must be essentially humanistic; that is, it must concern itself with the good for man; it must be first and foremost moral. The scientist frequently prides himself on the fact that morals are of no concern to him qua scientist, but by so doing he puts himself on a par with modern computing machines. He is a Frankenstein, no longer a human being. No man can be a better scientist than he is a man. It is this unnecessary hiatus between science and morals which is responsible for many of the woes of our age.

ONE more thing about the function of the teacher and about the joy of being a teacher and I shall have done. That is what, for lack of a more appropriate word, I shall call his pastoral function. This is the extra-curricular half of his profession, and it is often difficult to discern the boundary between the formal and the pastoral. The famous words of Terence, Homo sum; humani nil a me alienumputo* describe the nature and purpose of the humanistic teacher, that is, of every good teacher; for the good teacher is after all a teacher of men, not a purveyor of mere facts. Thus, some of his teaching may be done outside the class. A chance meeting on the campus, a student's call at the professor's office, a five-minute discussion at the end of a class with students eager to carry further an idea suggested during a lecture, these may often, be the theater in which the teacher plays his part. In my own experience, organized "advising" has not always been effective. On those occasions when the instructor is aware that the student wants and needs advice and the student realizes that he can talk to him, then something significant is achieved. It may be a comparatively trivial matter, the selecting of one course in preference to another, or it may be some heartbreaking grief, the loss of a parent or a broken family, leaving a boy lonely, unanchored, and afraid. At these times the teacher fulfills his pastoral office. Let me say that I have never felt profoundly sorry for the student of limited means. He always has a goal and a purpose. The children of wealthy parents have more often distressed me with their sense of the utter futility of life, with their lack of purpose, and their blindness to the glory of distant horizons.

Finally, a word as to the quickening spirit of the humanistic teacher. His views as a humanist may be personal and unorthodox. Naturally, he wants to supply the student with a certain body of facts together with their meaning. He is bent upon training men in the thoughtful and critical analysis of ideas. These are important and desirable in themselves, but the ultimate end of the teacher is to enable men to arm themselves to make decisions with courage and to face life with nobility. But man, whether we view him from the point of view of Platonic dualism or that of Christian dualism, is at once human and divine. The humanist's view, though not necessarily the same as that of the orthodox Christian, is akin to it. He envisions a trinity which is also a unity. The center of this is God in Christian terms or, as Heraclitus explained the Logos, "the intelligent, creating and guiding force of the Universe." The three rays emanating from God-Logos at the center are Goodness, Beauty, and Love. Finite man becomes aware of God-Logos through his apprehension of Goodness, Beauty, and Love. Also, as he becomes more aware of each member of the trinity, he grows more sensitive to each of its other members. This is the highest plane on which the humanist can teach. And the greatest of the three, as we know from Plato, from Saint Paul, and from Dante, is

L'amor che move il sole e I'altre stelle.

Dartmouth Teaching 150 Years Ago

THE excellent teaching available to Dartmouth undergraduates today was not matched in the early days of the College, the late Prof. Leon Burr Richardson 'OO states in his History of Dartmouth College. Writing of the time of President John Wheelock, he says:

"The point of view of the early Dartmouth teacher and his methods of instruction were not such as particularly to appeal to the modern educator. The conception seems to have been that the student should acquire the information of selected authors, and accept without question their conclusions. The main purpose of the recitation was to ascertain how well the student had performed that duty, rather than to supply him with additional information or to discuss various points of view. 'What does the book say?' 'What are the author's conclusions?' Such were the questions asked, not as preliminary to further development of the theme, but as the end of the matter. Then, as now, some of the students were very critical of the prevailing methods. Thus George Ticknor says of his undergraduate career:

"I learnt very little. The instructors generallywere not as good teachers as myfather had been and I knew it; so I took nogreat interest in study. I remember likingto read Horace and I enjoyed calculatingthe great eclipse of 1806 and making a projectionof it, which turned out nearly right.This, however, with a tolerably goodknowledge of the higher algebra, was all Iever acquired in mathematics, and it wassoon forgotten. I was idle in college, butI had a happy life and ran into no wildnessor excesses.

“... We are in a position to form a fairly definite judgment of the work in English composition, for many of the addresses prepared by seniors for Commencement have been preserved. Even for such productions they strike us as almost incredibly banal and commonplace in idea and as incredibly verbose and flowery in language. Literary tastes change with time, but it is not entirely that change of taste which would make such efforts, if presented to the instructor of freshmen today, an occasion of extreme disgust to that person whose capacity for disgust is so often tested. In truth, the boys, in most cases, had nothing to say, a situation which is by no means unknown to the modern undergraduate; but they were more successful in concealing that fact behind a barrage of flowery phrases than are their successors. In none of these respects, however, was Dartmouth essentially different from most other colleges in the country. The same educational philosophy prevailed in all, the same methods were followed, the same criticisms were made by the more forwardlooking or more disgruntled of the undergraduates, the same acceptance of the status quo was prevalent among the great majority of them. Under any educational system, however, individuals may exist with such outstanding characteristics that they make their influence potent, no matter what may be the handicaps under which they work. We find no such man among the earlier teachers at Dartmouth. The professors were men intellectually competent for the work which they were called upon to do, some of them were liked and esteemed by the student body, but none of them (except Nathan Smith, who had no part in regular undergraduate instruction) seems to have possessed such qualities as to make him a permanent factor in molding the character of those who came under his influence."

* I am a human being; and I consider nothing that is human foreign to me.

Professor Nemiah in his office in Dartmouth Hall

"The ultimate end of the teacher is to enable men to arm themselves to make decisions with courage and to face life with nobility."

The Author: Professor Nemiah was graduated from Yale in 1912 and received his Ph.D. degree there in 1916. He joined the Dartmouth faculty in 1919, became a full professor in 1923, and in 1938 was elected Lawrence Professor of the Greek Language and Literature. During his Hanover teaching career of nearly 35 years he has been a favorite professor of a great many Dartmouth men who took his courses in Greek, Latin or Classical Civilization. In addition to his courses in Greek and Latin, Professor Nemiah this year is teaching two courses in the Classical Foundations of Modern Society, and is chairman of Humanities 11-12, "Classics of European Literature and Thought."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's Faculty Policies

February 1954 By DONALD H. MORRISON '47h -

Feature

FeatureThe Teacher of Social Science and the World Crisis

February 1954 By JOHN CLINTON ADAMS -

Feature

FeatureMy "Most Unforgettable Character"

February 1954 By JAMES L. MONTAGUE '28 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

February 1954 By ERNEST H. EARLY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, RICHARD P. WHITE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1932

February 1954 By JOHN A. WRIGHT, JOHN B. WOLFF JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

February 1954 By TRUMAN T. METZEL, DR. COLIN C. STEWART 3RD

Features

-

Feature

FeaturePROJECT ABC

JANUARY 1964 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryChargé d'Affaires

April 1981 -

Feature

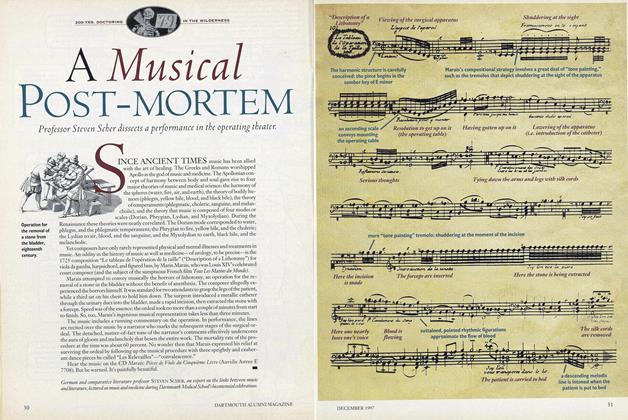

FeatureA Musical Post-Mortem

DECEMBER 1997 -

Feature

FeatureMerchant of Menace, Purveyor of Pleasure

JUNE 1977 By DAN NELSON -

Feature

FeatureThe Zen of Football

OCTOBER 1988 By Nick Lowery '78 -

Cover Story

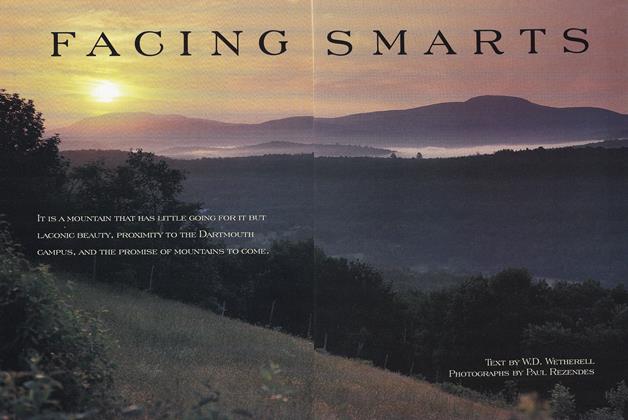

Cover StoryFACING SMARTS

Novembr 1995 By W.D.Wetherell