DEAN OF THE FACULTY

LAST September about thirty young teachers arrived in Hanover to begin their careers as members of the Dartmouth faculty. They came from a variety of college and university backgrounds, ranging geographically from Northern New England to Southern California. In welcoming them to the campus, The Dartmouth observed that the group was a first result of a recruiting program that would become more and more intense, and, as might be expected, it went on to tell the new teachers some' of the things that Dartmouth undergraduates expect of their teachers. Apparently what the students hope for is not too different from what the teachers expect of themselves. At any rate, there were no audible cries of dismay, and no resignations were tendered forthwith. In a full-time faculty of 200, thirty new members can have considerable influence. The observations that follow are intended to indicate the general context of policy and procedure within which members of the faculty carry on their work. Although teaching loads, course offerings, and other matters related to the curriculum are of great interest to all members of the faculty, they will not be dealt with in this article.

In 1946 the Board of Trustees set as a principal objective the maintenance at Dartmouth of a faculty second in quality to that of no other undergraduate liberal arts college. This fundamental objective guides the College's policies and programs in all areas affecting the faculty, including recruitment, promotion, and compensation.

What qualities are sought in prospectivefaculty members? Not many wise persons will specify confidently the qualities that characterize great executive or artistic ability and it is at least as difficult to define the characteristics common to outstanding teachers. Nevertheless, the effort must be made, and some qualities that lead at least to better than average teaching can be suggested. First, there is intellectual ability of a high order - a mind that is creative as well as critical, sensitive to the significant factors of problems, and able to relate and to see meaningful patterns in specialized knowledge and experience. Second, a sturdy, energetic personality, and character and integrity beyond question are essential. What a man is, as a human being, is as important to undergraduate teaching as what he knows or can learn. Undergraduates frequently are not interested in Medieval literature, or the most recent theory about the internal structure of the atom, but the impact of a teacher's quality as a human being can be a significant factor in the student's educational development, even when his interest in the course or lecture is somewhat less than vital. Third, the teacher should have the kind of enthusiasm for his subject that sustains creative effort over a long period of years and leads to an ever-deepening interest and competence. This is important because a member of the faculty who secures permanent tenure as a professor between the ages of 35 and 45 normally continues until his retirement twenty to thirty years later. Finally, the College seeks faculty members who have a lively interest in teaching undergraduates and, above all, enthusiasm for getting others to think for themselves. Is not the development of a creative and critical mind the best preparation for subsequent experience and the most certain of liberating influences? Dartmouth's central purpose is to help each student to reach his potential as a human being - to help him become a thoughtful and good man. Consequently, the faculty needs to be concerned with many aspects of a student's interests and not simply or even primarily with his capacity to absorb information.

With the exception of the undergraduate teaching interest, it will be noted that these qualities of the strong teacher are ones that lead to success in other, more lucrative professions. Consequently, in its search for faculty, Dartmouth must compete not only with other educational institutions, but also with business, medicine, law, engineering and other professions.

How does the College go about the taskof finding its teachers'? A first step is to identify trends in the subjects and disciplines represented in the departments, and to relate these to staff needs that can be anticipated by reason of scheduled retirements and other causes. This analysis leads to a statement of personnel needs, in terms of the years in which vacancies occur and of the particular qualifications to be sought in each replacement. The departments are making an energetic effort to establish and maintain close relationships with the best graduate schools. A faculty representative tries to visit the principal graduate departments annually, to apprise them of Dartmouth's needs for staff, of the professional and personal qualifications considered essential, and of the careers which their best young men may expect at Dartmouth. A relationship of mutual confidence is established with graduate teachers who are especially interested in the College and whose judgment of young teachers is reliable. Such teachers often can suggest the names of unusually fine prospects and they can be relied upon for honest, perceptive judgments of the relative strengths of candidates. These efforts are directed over an increasingly wide geographical area. It is no longer considered sufficient to take the best available from a few eastern universities. Our purpose is to be in touch with the most promising men available in the United States, and to interest them in a teaching career at Dartmouth.

What does the College expect of teacherswho are being considered for permanency? At Dartmouth a member of the faculty acquires permanent tenure when he is elected a professor by the Board of Trustees. A professor may not be dismissed except for cause, such as incompetency or misconduct. Instructors and assistant professors are appointed for terms of one and two years respectively. At Dartmouth as at other colleges and universities, the departments have primary responsibility for recruitment, appointments and promotions. Recommendations for appointments above the rank of instructor, and for all promotions, are reviewed by the faculty Committee Advisory to the President, comprising two members from each division (Humanities, Science, Social Science) appointed by the President from four nominees chosen by the divisional faculties, and the Dean of the Faculty. This review helps to insure that college-wide factors are considered and that uniform standards are maintained. The Board o£ Trustees has final responsibility for all appointments and promotions and it acts upon recommendations and information provided by the President and the Dean of the Faculty.

When considering promotion to an assistant professorship, the critical question is: Does the teacher have the essential qualities which, when further developed, may be within the competitive range of Dartmouth's standard for permanency? With respect to all promotions, therefore, the policy statement with respect to promotions to full professorial rank is relevant: "Recommendations for promotion to the rank of professor should be limited to men who are demonstrably superior as teachers or scholars. A bibliography is not a prerequisite for promotion. But if an individual has little or no interest in research or publication he should not be recommended for promotion unless he is, in the judgment of the department, a really distinguished teacher. Conversely, if a man's chief strength is research or creative writing, he should not be recommended for promotion unless he is also an effective undergraduate teacher." In short, Dartmouth can always use outstanding teachers who may not be researchers but as an undergraduate college she has few places for men who are not strong teachers.

One of the continuing debates in educational institutions is centered on the question of whether a man can be a good teacher unless he also engages in scholarly activity; or, as it is sometimes stated, whether a man can be a good undergraduate teacher if he neglects teaching in order to be a scholar. Why, it is asked, does a "teaching college" give any weight to a teacher's scholarly activities in considering him for promotion? Dartmouth's policy with respect to this question is based upon the belief that permanent tenure is one of the most precious awards that an institution can give; that it should not be given unless there is reason to believe that the individual will maintain the quality and vigor of his work over a long period of years; that creative scholarship is one of the ways in which competence is enriched and renewed; and that an ideal combination is the creative scholar whose knowledge and enthusiasm finds its principal expression, by his choice, in undergraduate teaching. Experience shows that such a teacher is likely to be an inspiration to his students, and the college's reputation as an educational institution is strengthened as he acquires a reputation for himself.

In short, the College expects that each teacher will have resources that will maintain the vigor and quality of his work over the long pull. It recognizes creative scholarship as one such resource, among others. And it values the individual whose research enlivens, enriches and sustains teaching competence, as well as the teacher whose enthusiasm and strength are renewed by other means.

What does Dartmouth do to help itsteachers develop their abilities to themaximum? A fully satisfying development of an individual's talents depends upon many factors, only some of which are related to his job and the conditions under which he works. But unless his work is carried on under circumstances that provide opportunity for growth, an able person is likely to seek this opportunity in new employment; or, if he does not do so, a growing sense of frustration tends to distort his judgment and inhibit his effectiveness. Consequently, it is not enough for Dartmouth to bring into the faculty promising young teachers; it must also seek, in positive ways, to encourage and support their growth. The College has many strengths, such as the traditional security of academic freedom, the extraordinary Baker Library, the quality of students, and the emphasis upon undergraduate teaching, that in subtle ways contribute to a teacher's development. Two other factors merit special attention.

First, there is the program of leaves of absences and of grants-in-aid which has as a primary objective the professional development of the faculty member. One of the principal opportunities is the sabbatic leave, which provides full salary for one semester or half salary for two semesters. During this time the teacher is free of teaching assignments and undertakes a project (for example, travel, research and writing, or government or business experience) contributing to his future effectiveness as a teacher. For men not eligible for a sabbatic leave, leaves with pay, or reductions in teaching assignments are possible to complete an important research or visiting job, or engage in activity clearly related to the improvement of the individual's teaching, or that of his department. Grants to cover travel expenses incurred in visiting other institutions, and attending professional meetings, and to provide secretarial and other assistance are also available. The College also does whatever it can to help faculty members compete for national awards; for example, the faculty fellowships offered by the Fund for the Advancement of Education for projects designed to improve the recipient's teaching (we have three applicants this year); the general education fellowships, supported by the Carnegie Corporation and the Rockefeller Foundation and enabling the recipient to observe undergraduate teaching at another institution (we had one this year and one last); and Guggenheim Fellowships, which are awarded to scholars, artists, and scientists of exceptional promise (in the last five years, we have had three in one year and one each in the two succeeding years, and have three applicants this year). Encouragement and assistance is also given to members of the faculty who seek outside financing for research projects in their special fields of interest. In the past year grants totalling about $100,000 were received from outside sources for this purpose. By these means, members of the faculty periodically are given full or part-time freedom from teaching responsibilities so that they may undertake activities calculated to further their professional growth.

The teaching internship program, begun this year under a grant from the Fund for the Advancement of Education, has the same general objective. In teaching as in other professions, it is probably true that one learns best by experience, and most quickly if initial experience is supervised. From the standpoint of both the undergraduate and the beginning teacher, it is desirable that the young teacher's abilities be developed as quickly as possible. The internship program attempts to accomplish this result by making available to the intern the regular and continuing counsel of an experienced mentor. There is a visiting back and forth of classes, with the intern learning by observation and through suggestion and advice. A seminar concerned with college teaching problems and methods is continuing through the year and is attended by the interns and several instructors not officially identified with the program. The seminar insures that the interns will give serious attention to teaching method as well as to the content of their lectures. Faculty members who participate in these discussions find the interns' questions provocative and on occasion have reported that a change in their own methods has resulted. Each intern has also been assigned several students on academic probation. The intern sees his "probationers" regularly and helps them to come to a better understanding of the cause of their difficulty. This phase of the interns' experience is proving unusually worthwhile. In his work with the experienced teacher, the intern has an opportunity to see some of the successes of teaching and to relate what he observes to educational theories and practices that are discussed in the seminar. The student of basic ability who is nevertheless on academic probation may represent, in some measure, a failure of teaching. The insights into this problem which the intern gains through counseling round out his experience and give him an opportunity to consider aspects of learning that otherwise would not come to his attention. Although the internship program is in its first year, there is a general feeling that it holds great promise as a means of accelerating the development of teaching ability and, hence, of improving the quality of undergraduate education.

What about the future? The quality of the present Dartmouth faculty was largely set about twenty-five years ago, when most of the men now in the professorial rank came to Hanover. As a group, the devotion of these teachers to their students and their loyalty and service to the College has been of outstanding value and is a tribute to the wisdom and judgment of those who selected them. Because they came at about the same time, and were about the same age, they retire at about the same time. Consequently, by 1966 about one hundred of these men will have retired. Taking into account their replacement and normal turnover, it is safe to estimate that at least two hundred and fifty faculty appointments will be made in a little over ten years. This replacement problem will hit Dartmouth during the period when national college enrollments are expected to double. Moreover, it has been estimated that there will be about three college teaching jobs available for every applicant. In short, Dartmouth must replace the core of its permanent faculty during a period of rapidly increasing college enrollments and of declining interest on the part of young people in going into the teaching profession.

Dartmouth's quality objective intensifies this problem. At the present time, it is not uncommon to find that of the ten top men completing graduate study in science in a first-rate department, not more than two will be interested in teaching in an undergraduate college. In other fields, the relatively low salaries paid to teachers have caused men who might make exceptional teachers to go into law, advertising, and other better paid occupations. Where this has happened, the kind of people that Dartmouth seeks for its faculty are relatively rare.

Can Dartmouth, under these circumstances, maintain a first-rate faculty? There are many favorable factors in the situation: Dartmouth's historic position and its growing national prestige; the general excellence of the physical plant and the exceptional quality of Baker Library; the traditional security of academic freedom; the possibilities for advancement during a period of re-building; and the attractiveness of Hanover as a community in which to live and raise a family. Since able men like to work with stimulating colleagues, the high quality of the present faculty is strongly in our favor. Recent recruitment has been guided by rigorous standards, yet in most cases we have been able to get our first choices.

Two factors are increasingly critical and require immediate attention—faculty compensation and faculty housing. As to compensation, the requirements will depend in part on national economic developments, in part on the salary schedules of the institutions with which we compete for staff, and in part on other actions that supplement and support the salary program. As to housing, apartments for families with not more than one child are relatively plentiful. But the College and the community do not have enough rental housing for families with two or more children. Faculty families needing more adequate housing have difficulty building at present costs and they have difficulty meeting the going rate on houses that are offered for sale. This need is now being studied and it is likely that reasonably adequate solutions will be found.

On balance, one can be confident of Dartmouth's ability to maintain the quality of its faculty in the difficult period ahead. The Trustees are fully aware of the significance of the problem and have assigned it top priority. The quality of the faculty has a direct bearing on the success of admissions and enrollment work, on the over-all quality of the College, and thus on its ability to attract needed financial support. If the faculty became less than it is, Dartmouth College could not long remain first-rate. This possibility is not in our plans.

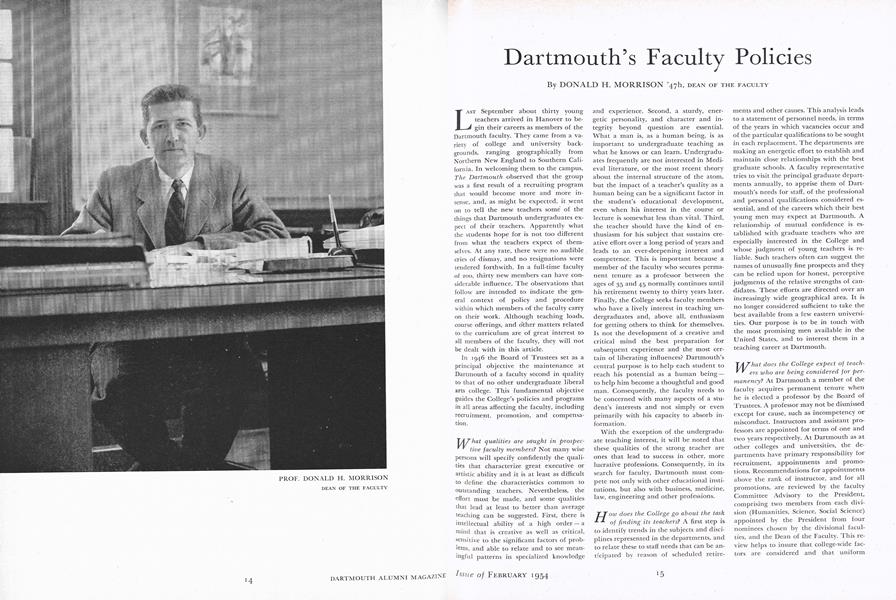

PROF. DONALD H. MORRISON

DEAN OF THE FACULTY

THE FACULTY'S THREE-PART ORGANIZATION consists of Divisions of the Humanities, the Social Sciences and the Sciences, each headed by a chairman who serves for three years. Shown here are (l to r) William A. Carter '20, Professor of Economics, who heads the Division of the Social Sciences; Robin Robinson '24, Professor of Mathematics, chairman of the Division of the Sciences; and Wing-tsit Chan '43h, Professor of Chinese Culture and Philosophy, who is chairman of the Division of the Humanities.

FRANCIS LANE CHILDS '06, Winkley Professor of the Anglo-Saxon and English Language and Literature, lecturing to juniors and seniors in his Shakespeare course. Senior member of the Dartmouth faculty, which he joined in 1909, Professor Childs will retire in June. He is chairman of the Committee Advisory to the Tucker Foundation, established in 1951 to further the moral and spiritual growth of the College.

BRUCE W. KNIGHT '34h, Professor of Economics, teaches economic principles and the economics of international peace. A member of the faculty since 1924, he has written three books, one of them on "How to Run a War," and could easily do a fourth on baseball statistics.

ARTHUR O. DAVIDSON, Assistant Professor of Education, joined the Dartmouth faculty a little over five years ago. In addition to his courses, he handles teacher placement and is active in the effort to interest more liberal arts graduates in a teaching career.

LOUIS L. SILVERMAN '2411, Professor of Mathematics on the Chandler Foundation, once told a student interviewer, "I love to teach for the sake of teaching." He has been putting this into practice at Dartmouth since 1918 and retires in June with the well-deserved reputation of being one of the College's finest teachers.

ANDREW J. SCARLETT '10, New Hampshire Professor of Chemistry, conducts the large lecture course in General Inorganic Chemistry. He has taught at Dartmouth continuously since 1917 and during the war years held the important faculty post of Chairman of the Educational Policy Committee. In recent years he has made a study of plastics.

CHARLES R. BAGLEY '32h, Edward Tuck Professor of the French Language and Literature, prefers to hold tutorial sessions at his home and is shown there with two of his junior-class students. He has written three books on French literature and famous men and women of France, and in 1945-46 was visiting professor and tutor at Oxford, where he was a Rhodes Scholar and later took honors in graduate study.

FRANCIS W. GRAMLICH '48h, Professor of Philosophy, teaches courses in American philosophy and the problems of human nature. He is also a member of the inter-departmental staff conducting the new course in Human Relations and is shown above in the course laboratory.

FRANK G. RYDER, Professor of German, also teaches Japanese and is here helping a student in that course. Spare time for his verse translation of the "Nibelungenlied" was recently reduced when he was made chairman of the Commission on Campus Life and Its Regulation.

EDWARD A. BEVAN, Instructor in Genetics, is shown working with two zoology students in an advanced course in which the undergraduates are carrying out their own research investigations. In science courses of this nature the students receive very personal instruction and guidance and gain a valuable knowledge of scientific method as well as fact.

RICHARD B. McCORNACK '41, Assistant Professor of History, teaches the history of the Latin American Republics, a specialty he began as a Senior Fellow at Dartmouth. After serving with the Navy in Panama and doing graduate work at Harvard, he joined the faculty in 1947.

LESLIE F. MURCH '22a, Professor of Physics, whose affable nature makes him one of the most popular members of the Dartmouth faculty, teaches the large courses in elementary physics. His basic course required of Navy V-12 trainees during the war was known as "Murch's Mystery Hour." He has published one physics textbook and two laboratory manuals.

ROBERT K. CARR '29, Parker Professor of Law and Political Science, teaches government courses dealing with Congress, the Supreme Court, and constitutional law. He was executive secretary of the President's Committee on Civil Rights and has written a book on that subject.

The Author: Dean Morrison was graduated from the University of West Virginia in 1936 and holds both the Master's and Doctor's degrees from Princeton. For three years before joining the Dartmouth faculty in 1945 as Assistant Professor of Government, he was administrative analyst and budget examiner with the Bureau of the Budget in Washington. He was promoted to full professor in 1947, and on July 1 of that year became Dean of the Faculty at the age of 32. Dean Morrison continues to hold the rank of full professor in the Department of Government. As Dean of the Faculty, he serves as executive officer on all faculty matters, including personnel, and as liaison between the teaching staff and President Dickey. A member of several major committees, including that on educational policy, Dean Morrison has a vital and influential interest in the courses offered at Dartmouth and in teaching methods.

"Intellectual ability ... character, integrity ...enthusiasm for his subject ... a lively interestin teaching undergraduates ...”

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureTestament of a Teacher

February 1954 By ROYAL CASE NEMIAH '23h -

Feature

FeatureThe Teacher of Social Science and the World Crisis

February 1954 By JOHN CLINTON ADAMS -

Feature

FeatureMy "Most Unforgettable Character"

February 1954 By JAMES L. MONTAGUE '28 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

February 1954 By ERNEST H. EARLY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, RICHARD P. WHITE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1932

February 1954 By JOHN A. WRIGHT, JOHN B. WOLFF JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

February 1954 By TRUMAN T. METZEL, DR. COLIN C. STEWART 3RD

Features

-

Feature

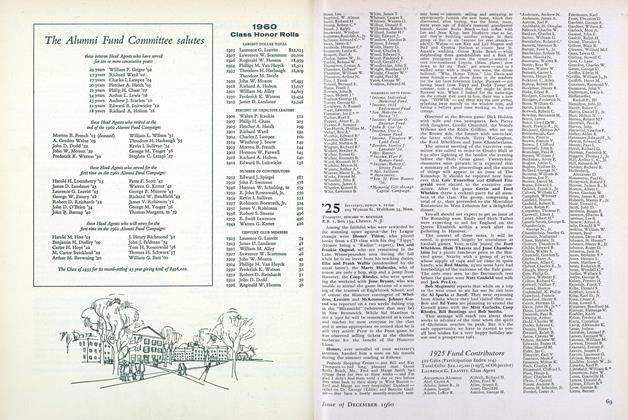

Feature1960 Class Honor Rolls

December 1960 -

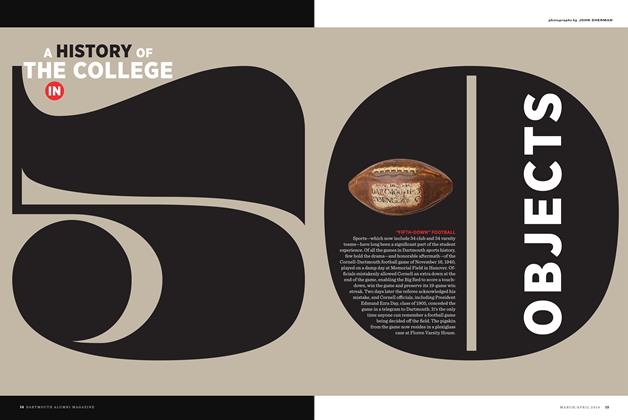

Cover Story

Cover Story"FIFTH-DOWN" FOOTBALL

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

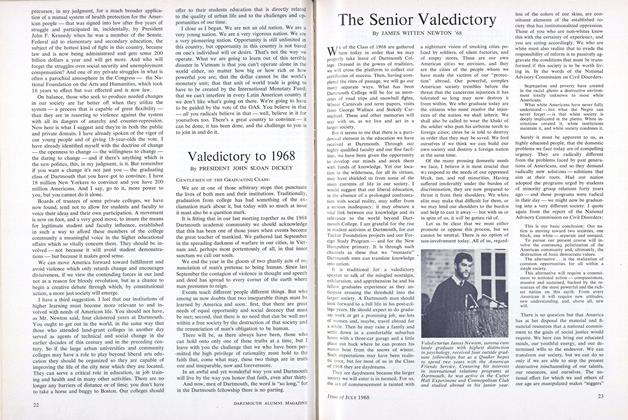

FeatureThe Senior Valedictory

JULY 1968 By JAMES WITTEN NEWTON '68 -

Feature

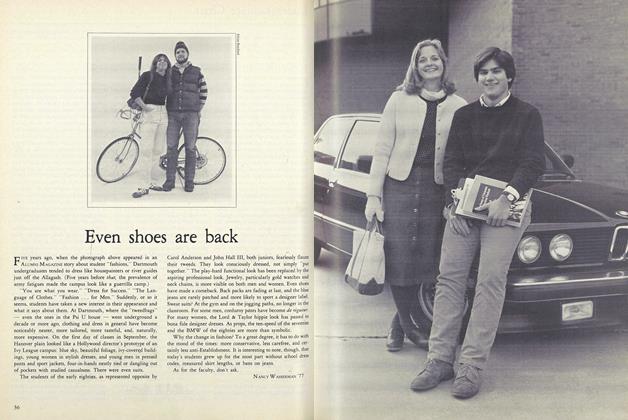

FeatureEven Shoes Are Back

DECEMBER 1981 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Feature

FeatureAn Environmental B

Winter 1993 By Noel Perrin -

Feature

FeatureThe Second Emancipation

JULY 1963 By THE REV. JAMES H. ROBINSON, D.D. '63