New revelations on

"FAIR OF FACE, Joyous with the Double Plume, Mistress of Happiness, Endowed with Favour, at hearing whose voice one rejoices, Lady of Grace, Great of Love, whose disposition cheers the Lord of the Two Lands."

With these felicitous epithets, inscribed in stone more than 3,300 years ago on the monumental stelae marking the boundaries of the great new city at Tell elAmarna on the Nile in central Egypt, the Pharaoh Akhenaten described his chief queen, the beautiful Nefertiti. Until very recently, archaeological discoveries have done little more than pique our curiosity about this glamorous woman and her strange husband and a reign so extraordinary that their successors attempted to obliterate completely all reference to them. More, indeed, is known about the comparatively unimportant boy-pharaoh Tutankhamen, their son-in-law.

Why, for example, did this gorgeous girl marry a man widely portrayed as having a monstrous appearance? Did she really fall in love with him? Or did Akhenaten, infatuated with her and possessed of unlimited power, force her to marry him? Was he ever able to make her overlook his repellent ugliness? Were his tributes to her the desperate attempt of a love-sick ruler to gain the affection of a wife who never wanted to be the queen of a repulsively deformed man?

Although none of these questions can be answered with certainty, the years of research which I organized as director of the Akhenaten Temple Project at the ancient capital at Karnak, or Thebes, have thrown much new light on Nefertiti. The deliberate destruction of evidence concerning the reign of Akhenaten by the traditional pharaohs who followed him was successful enough that some early standard works on Egyptian history never even mentioned the lovely Nefertiti. No one, prior to our project, had recognized her true importance.

It was the discovery and careful study of some 35,000 blocks of sandstone, commonly called "talatat," that had been placed in the walls of buildings constructed by Akhenaten, which gave us sufficient clues even to ask the questions we hope one day may be answered. These structures had been built early in Akhenaten's 12- to 16-year reign to honor the sun disk, which the pharaoh decreed to be not only the supreme deity but the only one. When these structures were dismantled, soon after his death, some of the carved and painted talatat were moved by his successors and used as filling within the huge stone pylons at Karnak; others were found stacked in the open near the splendid Temple of Luxor; still others have been recently scattered illicitly throughout Egypt, western Europe, and the United States.

Realizing the practical impossibility of physically rebuilding any of the dismantled buildings, we decided to use the modern capability of the computer to reconstruct on paper this marvel of the ancient world. After I had first seen the talatat at Karnak, I discussed the problem with President Kemeny, then a professor of mathematics at the College. He was enthusiastic and gave me valuable suggestions as to how to proceed.

First our staff photographed each block in identical scale and ascribed a number to it. Then the most 'detailed description of each — as to dimension, condition, subject matter, presence and position of any remaining flecks of color — was recorded, to be fed into a computer at Cairo. After all the information on all the talatat we were aware of near the sites and elsewhere was recorded and carefully organized, we were able to use it as needed to match the block photographs into their correct original groupings.

Let us assume, for example, that at a given moment we wished to find out whether we had found the talatat immediately below one which showed a part of Nefertiti's head. The computer could tell us by means of print-outs of coded information whether a photograph of a block with the required subject matter in the correct proportion was on file. Likewise, we could match one block showing rays emanating from the sun disk at a certain angle with another, or others, which had been adjacent to it. It is from the photographs of these blocks reassembled to show correct sections as they had appeared on the walls of Akhenaten's buildings that we have discovered more than ever was known before about Nefertiti.

We have learned, for instance, that she was considered to be divine and that prayers were addressed to her. We have uncovered, for example, evidence of her importance in an official announcement to the people of her approval of the transfer of the royal court from Karnak to Amarna, 240 miles north down the Nile. We have seen the tremendous emphasis placed on the queen in a large number of scenes in which she is participating in offering ceremonies, often with no evidence of the presence of the pharaoh. The prominence given her likeness on pylons and gateways is a measure of her importance, and her portrayal in exactly the same posture as the pharaoh in offering scenes indicates her religious stature.

The most remarkable symbol of the deference accorded her is the enormous courtyard built in her honor at Karnak — its towering pillars decorated with multiple images of Nefertiti facing herself across offering tables, the rays from Aten focusing on her, without a hint of the existence of Akhenaten. In the absence of even male animals on the richly decorated pillars, Nefertiti's courtyard seems dedicated not only to her royal person, but to femininity itself.

Their successors went so far as to strike Akhenaten's. name from.the list of kings, and both his and Nefertiti's titles were removed from carvings and friezes. Her image was brutally defaced; the human hands terminating the rays of Aten which shine upon her were slashed; and reassembled segments of pillars from her courtyard were placed, many upside down, under the massive outer walls of a pylon, as if to crush her symbolically beneath their enormous weight. This systematic destruction was most probably carried out by the Pharaoh Horemheb, who completed the restoration of the orthodox polytheism following his assumption of power some 13 years after Akhenaten's death. He had been a ranking general of the army during Akhenaten's reign and King's Deputy under the boy-pharaoh Tutankhamen, who left no heir.

No doubt there was some propaganda value for Horemheb in a public display of his animosity for the queen and the religion she espoused. As a powerful member of Akhenaten's court, he must surely have followed his pharaoh in worship of the sun disk. Perhaps he hoped the recollection of his heresy would be erased by the fury of his vengeance against the memory of Nefertiti. It may also have been that the queen was the more devout of the royal couple in her monotheistic reverence for the Aten after Akhenaten's faith conceivably wavered toward the end of his reign. Some authorities have speculated that this may be one reason for an apparent estrangement between the pharaoh and his queen.

FOR REAL insight into the reasons, aside from her fabulous beauty, for Nefertiti's strong public impact and the vehemence of the subsequent reaction to it, we must take into account the cultural and religious climate of Egypt in the middle of the second millenium before Christ — and how drastically Akhenaten deviated from it. In what is known as the XVIII Dynasty, Egypt was a rich agricultural land, nurtured by the periodic flooding of the Nile, the center of an empire that extended as far as Syria. The family was the basic social unit; vocations, including kingship, were handed down from one generation to another, the military offering almost the only opportunity for advancement; and a vast bureaucracy of scribes conducted many affairs in the name of the pharaoh.

The pharaoh was traditionally a godking who owned his empire, who made the Nile rise and fall at the appropriate season, who held power of life and death over his subjects. He was "born to rule while yet in the egg," and on his death he was reabsorbed into godhead, to be replaced by the next god incarnate. He was at once the son of Re-Atum, the sun god and creator of the universe, and the living Horus, the sky god who took shape as a falcon; when he died, he became Osiris, the father of Horus. In more militant dynasties, pharaohs were sometimes held to be incarnations of war gods.

As deities incarnate, begotten by gods in the form of kings, pharaohs were not subject to the laws applied to mortal men, including incest taboos. To the contrary, to preserve the purity of the royal solar blood, the ideal match was between the Crown Prince and the Royal Heiress, eldest son and eldest daughter of the pharaoh and his chief queen — a tradition still in force in Cleopatra's time, 1,300 years later. Since the throne may have been literally part of the heiress' dowry, pharaoh became pharaoh through marriage to her. If there were no son by the chief queen, one by a concubine was next best. If no direct male heir survived — infant mortality rates were, of course, staggering — the closest collateral relative or the son of a powerful court family had to do. Lacking a royal heiress, chief queens were chosen in similar fashion. Foreign marriages were routinely contracted by pharaohs for diplomatic reasons.

Akhenaten's father was Amenhotep III; his mother Tiye, considered a commoner, is thought to have been the daughter of the old pharaoh's Master of the Horse. Ordinarily, Akhenaten would have married his sister, the royal heiress Sit-Amun, but for some unclear reason their father Amenhotep departed from tradition by marrying her himself.

Regarding the antecedents of Nefertiti, there has been much speculation but of course no firm evidence. In view of her rather un-Egyptian features, some authorities think she was a Babylonian princess, sent to Amenhotep's harem for a marriage of diplomacy shortly before the old pharaoh's death. It is my view, however, that she was a daughter of Ay, brother to Queen Tiye, hence a cousin to Akhenaten.

Since Nefertiti bore only daughters and Akhenaten may not have had sons by concubines, Smenkhkere and Tutankhaten — who may have been his younger brothers or half-brothers - were married to the first and third of the royal princesses, respectively. The second daughter, whom Akhenaten seems to have married himself fairly late in his reign, died early, probably in childbirth. Sme'nkhkere shared rule briefly as co-regent with his father-in-law/ brother and died within a year of Akhenaten. Tutankhamen died before he was 20 without issue, his wife having produced only two still-born daughters whose bodies were found with his in the celebrated tomb. Tutankhamen's widow, to keep it all in the family, hastily married her grandfather Ay, the last pharaoh before the iconoclastic Horemheb.

VENERATED by some Egyptologists as the first monotheist, the first idealist, the first internationalist, the first true individual, "the most remarkable figure of the ancient world before the Hebrews," Akhenaten scandalizes others as a monster or a religious maniac.

In a civilization that worshipped different gods at different times for different reasons, Akhenaten elevated the Aten, a deity rising in favor even during his father's regime, to the supreme and then the sole position. Represented as an abstraction rather than in traditional human or animal form, the sun disk was depicted as conferring on the royal family, through its rays and hands, the breath of life and truth — and the divine power of heaven. So zealous was the young pharaoh for the cult of the Aten that he downgraded the powerful priesthood of the Amun, the chief god of Thebes; decreed an end to the plural form of the word "god"; changed his name from Amenhotep IV (Amun is satisfied) to Akhenaten (He who is useful to Aten); and raised the great buildings at Karnak, Luxor, and Amarna. In the sixth year of his reign, he abandoned the old capital at Thebes to take up residence in the new city he had had built at Amarna, which stretched some four miles along the Nile and which he named Akhetaten (Horizon of the Disk).

During Akhenaten's reign, the pharaoh became a more human, more realistic figure, in contrast to the aloof, heroic warrior-kings of earlier days. Scenes we have reassembled show an extraordinarily cosy picture of domestic bliss: Akhenaten and Nefertiti holding hands; riding in a chariot, her face raised toward his in a pose quite inappropriate to ruling monarchs; dandling their children on their knees; chucking them and each other under the chin. The divine family, beloved of Aten, is portrayed as adoring and being adored, the disk's rays streaming down overall.

The scenes also show, very clearly, the bizarre physique and physiognomy of the pharaoh, perhaps a legacy of his inbred ancestors. His figure, effeminate enough to make it occasionally difficult to distinguish between statues of the king and of the queen, displays well-developed breasts, a pendulous paunch, broad hips, heavy thighs and buttocks, and spindly lower legs. His face is elongated; the chin large, pointed, and drooping; the lips thick; the cheeks sunken. His head is covered by a crown or a wig, but the skulls of the royal princesses are portrayed as grossly deformed, indicating the possibility of an inherited hydrocephalus. Some medical authorities hypothesize that Akhenaten — and, to a less degree, others in his family — may have suffered from a pituitary deficiency such as Froehlich's syndrome. In the early days of his reign, at least, Akhenaten's deformities were realistically depicted, perhaps even exaggerated, and others in the royal family, Nefertiti included, are shown with strikingly similar features. Since it would be unthinkable for sculptors to portray the pharaoh so grotesquely without his clear consent, it seems possible that he was pleased with his appearance as evidence of his difference from common people.

A particularly puzzling reminder of the pharaoh's strangeness are 15 colossal statues at Karnak, which show Akhenaten naked and even without genitals. These statues were lined up at the royal palace, and fragments of similar statues were found at the Amarna palace. There has been a good deal of speculation as to whether his physical anomalies may have rendered him sterile and, hence, as to who might have sired Nefertiti's daughters. Most authorities, however, prefer to assume, as I do, that Akhenaten was capable of paternity.

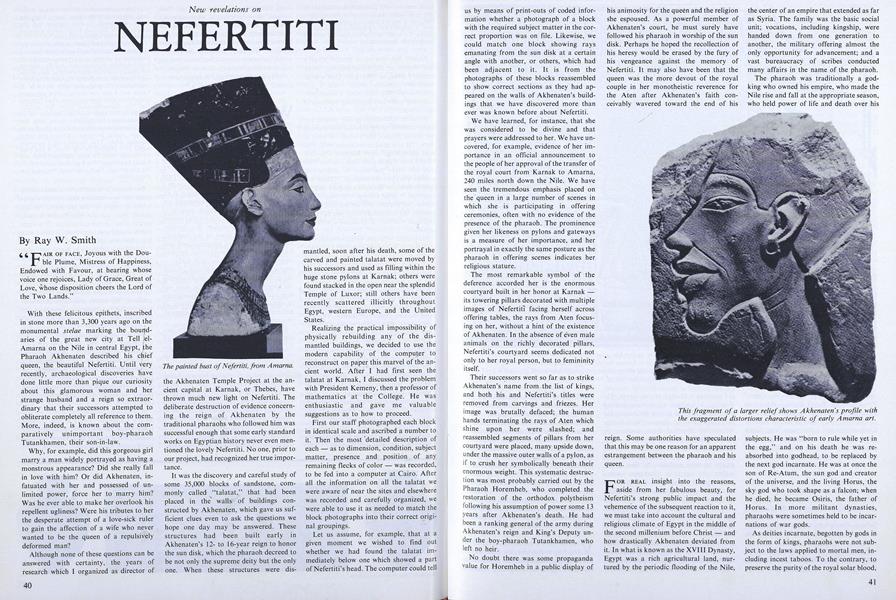

In the early years of Akhenaten's reign, Nefertiti was often shown on talatat with a near resemblance to the grotesque facial features of the pharaoh, which of course proves nothing about her actual appearance. In the later years of Amarna art, portrayals of Akhenaten were much more restrained and Nefertiti was seen in all her beauty. In fact, the famous painted bust of her which is on exhibition in a German museum suggests that she may have been the most beautiful woman who ever lived. I have the good fortune to own the first, if not the only, copy made from the original, the fragments of which were found by a German archaeological group in an ancient sculptor's workshop at Amarna.

Perhaps the change in the treatment of Nefertiti at the hands of the artists, from the gross ugliness shown early to the glorious beauty of the later work, is a reflection of an increase in her public esteem. Very likely this glamorous woman became eager to have her physical charms accurately portrayed rather than permitting herself to be used to satisfy the vanity of a man for whom her dedication had perceptibly dimmed.

Since the tombs of Akhenaten and Nefertiti have never been found, we have no precise information about her disappearance from the royal court or the disposition of her body. My own surmise is that she outlived Akhenaten by several years. She seems to have left the palace and moved to quarters at the north end of the city of Akhetaten, where she may have lived with Tutankhaten — as he was then known — and his wife, her daughter Ankhesenpaaten. Since there is reason to believe that she was the more steadfast of the royal couple in her monotheism, perhaps her death may have been the signal for the boy king to change his name to Tutankhamen and to abandon Amarna to return to Karnak.

Whatever the talatat or further archaeological discoveries may reveal in the future about the strange alliance between the monstrous Akhenaten and the beautiful Nefertiti, there seems little doubt that their estrangement was complete and that whatever cordiality had existed between them was dissipated before the end of Akhenaten's reign.

The painted bust of Nefertiti, from Amarna.

This fragment of a larger relief shows Akhenaten's profile withthe exaggerated distortions characteristic of early Amarna art.

Akhenaten, left, ' and Nefertiti, strikingly similar in profile, play with three of theirdaughters in happy domesticity. Aten's rays, ending in human hands, confer the breath oflife and power on the royal couple. Note the elongated shape of the princesses' heads andcarving under Nefertiti s chair, which is probably indicative of her importance.

A seemingly androgynous Akhenaten as depicted in one of the huge statues at Karnak.

Ray Winfield Smith '18, an adjunctresearch professor at the College andrecipient in 1958 of an honorary D.H.L., isa native New Hampshire man who hasmade the world his field of interest asbusinessman, soldier and foreign-serviceofficer. He is an internationally knownauthority on ancient glass as well as anEgyptologist. His book The Akhenaten Temple Project, Vol. I, Initial Discoveries has recently appeared.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureStalking the Student Athlete

March 1978 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureThe New Classics

March 1978 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureFaces in the Gallery

March 1978 -

Article

ArticleAn Untraditional Path

March 1978 By A.E.B. -

Books

BooksNotes on a Yale man's journal and the 'elbowing self-conceit of youth.'

March 1978 By R.H.R. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1948

March 1978 By FRANCIS R. DRURY JR.

Features

-

Feature

FeatureNugget to Times Square

January 1974 -

Feature

FeatureAn Irresistible Force?

September 1975 -

Feature

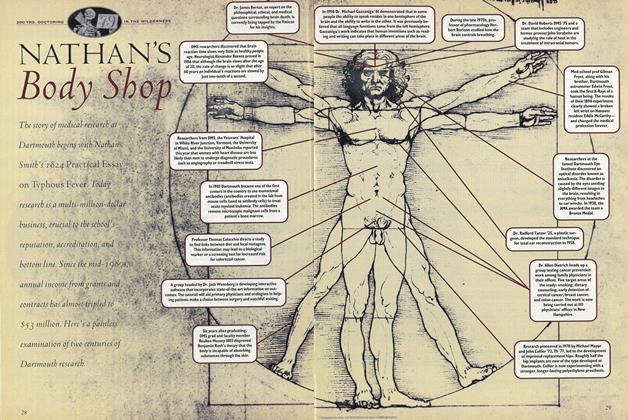

FeatureNathan's Body Shop

DECEMBER 1997 -

Feature

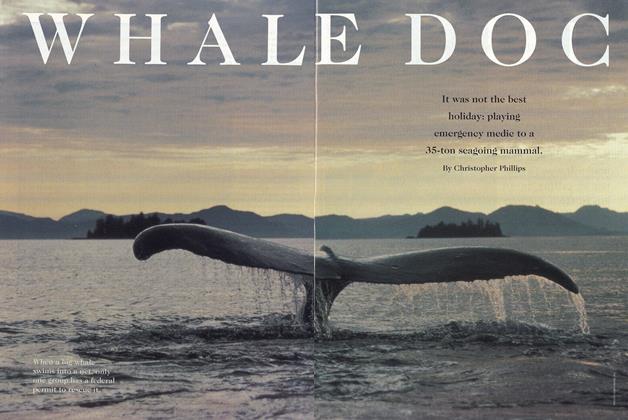

FeatureWHALE DOG

FEBRUARY 1994 By Christopher Phillips -

Feature

FeatureThe Blackman Era: Sixteen Special Years

FEBRUARY 1971 By JACK DE GANGE -

Feature

FeatureLife After the Presidency

NOVEMBER 1984 By Shelby Grantham