JUST before spring vacation the campus voted that by 1960 chapters of national fraternities must drop their racial-religious bars or go local. The referendum affects six houses which have "written" discriminatory clauses and about six more which have "unwritten" clauses, or over half the College's fraternities.

This is a rare instance, perhaps the first, where a student body, rather than a college administration or a state legislature, has issued a flat ultimatum to the national fraternities. The news spread fast. In the following week we were cornered by men from Yale, Cornell, Princeton and Harvard. The wire services, the New York and Boston papers, and at least one magazine carried the story with varying sihades of error. A New York Herald Tribune editorial kaileci it as a narrow victory of liberals over bigots, wheereas in fact it was a choice of means taken by men who agree unanimously on the end. But the point is, the referendum was big news, rating editorial space in a leading national newspaper, right alongside the battle reports from Indo-China.

Perhaps it is not too much to say thal this decision is a by-product ok World War II. For it was the veterans who first made an issue of the conflict between the policies of a liberal arts college and those of the fraternities cradled within the college. They were the first to be noisy about this chasm between the ideal, for which they went to war, and the real — between the principle and the practice.

The vets' outcries culminated in a referendum held in 1950, much like the one conducted by the Undergraduate Council last month. At that time, by a margin of 500 votes the students ruled that chapters of national fraternities with discriminatory clauses must take every possible measure to get rid of them short of goinglocal. Each "clause house" organized an action committee to petition alumni and other chapters and to lobby at conventions, while the Interfraternity Council coordinated their efforts and the Undergraduate Council acted as watchdog.

Consequently, one national fraternity of the eight then with clauses dropped its bars - so it seemed. But in fact that house took its prejudice "underground." In executive session it re-defined what it meant by "socially acceptable."

And last year the UGC ruled that the local chapter of Theta Chi hadn't done enough. It was about to ban the house from interfraternity activities, including rushing, which adds up to dissolution, when the local brothers defied their national. They declared they no longer recognized "anything which might be construed as being discriminatory" in the national charter. They were kicked out.

Meanwhile, the other houses were getting a picture of the size of their problems. Some had to get a vote on the legality of amendments before they could even introduce one. Others brought the issue to a vote, and generally found they were in a one-third minority or worse. Guesses as to the time needed to get rid of the clauses, at what was then the rate of advance, ranged from ten years up to fifty and over.

There was enough despair by last year to merit a poll measuring the "go-local" sentiment. Results showed that many men were interested in going local if everybody else did it.

This brings us to the March referendum. Of 2,248 ballots cast (an 86.5% turnout), 1,128 voted for Point One (to impose the six-year deadline), 848 for Point Two (every step short of going local), 272 for Point Three (leave it alone). Each class favored Point One, by margins ranging from three (the sophomores) to 108 (the juniors).

Both sides campaigned heatedly, and with some bad feeling. There were debates in Dartmouth Hall and over WDBS; proponents of Point Two passed out literature; The Dartmouth's columns were so filled with letters there was little room for editorial comment. Most everybody took sides — an IFC majority for Point Two, the DCU Political Action Commission, the Human Rights Society and TheDartmouth for Point One,

In pitifully small capsule form, here is about the way the arguments ran: defenders of the status quo said that progress is being made, but that a six-year deadline is so short it means sure death for the national houses, and that forcing houses to go local this way is neither morally right nor strategically wise because it calls a halt to a national crusade which Dartmouth chapters are leading. Defenders of Point One said that little progress is being made at the present rate, that the six-year ultimatum would force redoubled local efforts and would soften up the nationals, that Dartmouth can't wait 25 years, and that the "crusade" business is hooey because dropping the clauses only lets the unprejudiced people be unprejudiced, while the bigots do as they please.

Now that the decision has been made, and the bad feeling has given way to a common determination to really work for the next six years, one tough problem looms. The referendum is supposed to cover "unwritten" clauses as well as "written" ones. These camouflaged bars are often stuck in "sacred," secret house ritual or other hideaways. A determined sleuth, .however, usually can find out where they are - so long as they are explicit. But the term "unwritten clause" has come to include implicit, discrimination - verbal understandings, such as "if you guys pledge a Negro, ten southern chapters say they'll withdraw; so if there's a showdown, we'll have to kick you out instead."

Sort of like the Stevens-McCarthy-Cohn hassle, with the Undergraduate Council as referee.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureTHE CREATIVE ARTS

May 1954 By IRWIN ED MAN -

Feature

FeatureSinging Ambassadors

May 1954 By ROBERT K. LEOPOLD '55 -

Feature

FeatureThayer School's Fire Bug

May 1954 By FRANK PEMBERTON -

Feature

FeatureON THE AIR 16 Hours a Day

May 1954 By DONALD R. MELTZER '54 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

May 1954 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, GEORGE E. REDDING -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

May 1954 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, RICHARD A. HOLTON

DICK MAY '54

-

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

November 1953 By Dick May '54 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

December 1953 By DICK MAY '54 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

January 1954 By DICK MAY '54 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

March 1954 By DICK MAY '54 -

Article

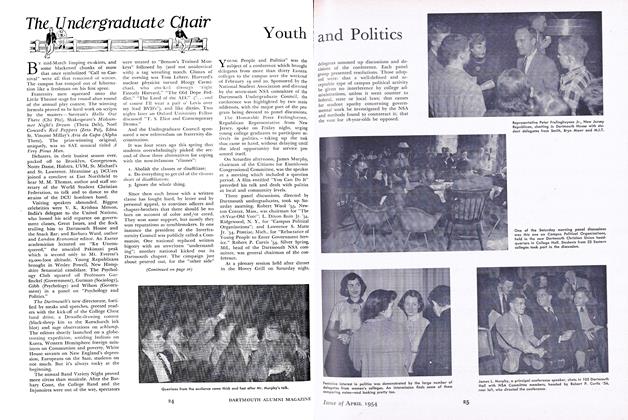

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

April 1954 By DICK MAY '54 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

June 1954 By DICK MAY '54