EIGHT months is too long to sit in any chair.

"Eight months is too long for anyone to sit in a chair," reflected Dick Cahn '53 in these columns just twelve months ago. That was a good line. When you sit too long your legs go to sleep. They don't want to march in parades, say, or in Com- mencements.

It's time we got up and stomped around a bit. It also is time to cast off the protective, constricting armor of an "editorial we." This phony omniscience has served well to guise "our" private opinions under a shield of collective "editors" and collective "students." It also has been a strait-jacket, forcing the writer to try, at least, to make the "we" represent a consensus of student opinion. Now, en route to the wide world, I want to say some personal, parting things about Dartmouth College.

I was taught here that there are two ways of being loyal to an institution. One is to idolize it, as pristine and perfect. In politics this sort of attitude is called Conservative sticking to things as they are or "just like they were in the good old days." I think this is the kind of loyalty felt by most alumni, whose ranks I am soon to join.

The other kind of loyalty is aspiration. Its strongest expression of love for an institution is the desire to perfect it according to its own ideals, in politics this sort of attitude is termed Liberal - being eager to experiment, to tamper, to change. This is my feeling about the College. I am loyal to what might have been. I will contribute to the Alumni Fund for life so the College can become what it was not, when I was there.

And here are some of the things I would change.

I'd chuck the first two years of the curriculum back into the ashcan whence they came. Here is why.

Today the College is working to smooth out the social transition from home and prep school to freedom. That's fine. But the intellectual transition should be anything but smooth. Terrifying, exciting, challenging - anything but smooth. Instead the first two curricular years here are as dull as any high school class in sentence diagramming.

The sixteen "prerequisites" I had to take cost my father $1280, or over three cents per classroom minute. They cost me 672 classroom hours. There were sixteen of these required courses in two years: four social sciences, four natural sciences, four languages, two English, two Humanities.

Except for the Humanities and one outstanding science course, this exposure to academic life soured me on book learning. I turned to extra-currics, because they were exciting while the heart of the College, the curriculum, was not.

These courses are bad for two reasons.

First, their scope is narrow. Government 1, for example, is highly specific about "the organization, powers and functioning of the Presidency, Congress, and the federal courts," along with "special emphasis upon contemporary problems and policies." Last year I happened onto a course dealing with the origins of government, with where government fits into people's lives, with the assumptions behind various systems of government. This was my "introductory" course; the other was highly specialized. In the same way, I have just finished a course - in the last semester of my college career - which truly introduces the subject of psychology. It deals with the origins, the various schools, the findings and the limitations of psychology. Unlike the alleged "introductory" psych course, this one has breadth.

As for the language requirement, this is the biggest lower-division hurdle. It takes the most time and flunks the most men. It is also the least rewarding. Studying a language is for most a painful process quickly, gratefully forgotten. The grammar rules can't be remembered, the civilization cannot be savored because of the ever-present grammar rules, and the paltry amount of spoken language taught is not retained because it is not used. A foreign language is a priceless thing if immediately needed. Those who need a language will choose to study one. Why compel the others?

The most lethal failure of the lower-division curriculum is in natural sciences. I am graduating from college with the barest notions about the movements of the cosmos, the evolution of the earth, the rudiments of biology. I know least about the principles of science, or its essential techniques and limitations. Worse yet, I know few "science" majors who think about the implications of their discipline. They know only ritual and technique. The ignorance of both scientists (qua technicians) and laymen about science can be the death of us in this atomic age.

Now the second bad thing about lower-division courses, besides the way they are conceived, is the way they are taught. The older, and presumably wiser, teachers shun the dull routine of "introductory" courses, for good reason. The courses are pure time-serving for both students and teachers. There is no creative thinking involved, only rote memory of pre-digested textbook aphorisms.

The College should scare the mental britches off new students. It should show them in short order that cozy family maxims are not principles, that rote memory is not creative thinking, that what was good enough back in Paducah isn't good enough in college. Dartmouth should let its new students find out fast

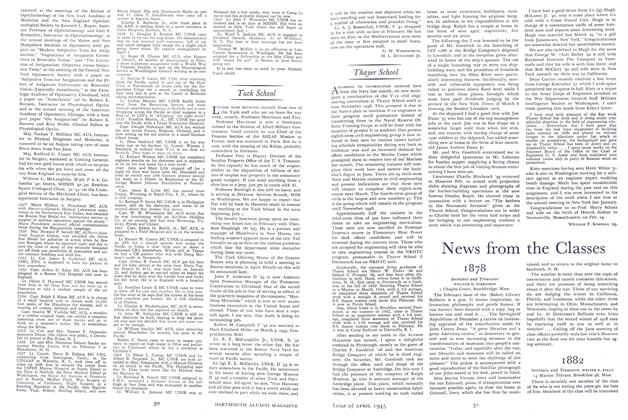

Maine's Winning Teamwork at Woodsmen's Weekend

(1) how pitifully little they know,

(2) how much there is to be learned,

(3) how important it is that they learn.

If the College gave its best to the new men, and demanded their creative best, the last two years would pretty well take care of themselves.

Next, I would make the College coeducational.

Today in Hanover we have a precious asset: remoteness. Being geographically outside the main stream of current events, we can gain a perspective; we can take the "long view" of things. We can talk about principles and ideals. We can study the contrast between principle and practice. That's right — we can live in an Ivory Tower.

But we don't make use of this asset because the girl friend is so far away a student has to tear off for that Big Weekend - make up for lost time. That's why Dartmouth men get labeled revel-rousing, in-town-again Indians. When the public sees them, they are noisily forgetting they are intelligent creatures.

I'd like to get rid of this obsession for getting out of town. I'd also like to get rid of what is politely known as the campus drinking problem, along with the mutts and the tramps. I'd like to cut out the unnatural tension that goes with being a Dartmouth man among collegiates. Little of this tension is creatively "sublimated," as the psych profs say. It builds up until it explodes in a drunken party, a crackup on the road, a New Hampshire Hall case.

So I'd make the College coed. No kidding.

Finally, I would tinker with this business of Purpose.

It was the president of an institution in the Boston vicinity who said. The true business of a liberal education is greatness." That, I think, is the goods. I think my father gave me a liberal arts education hoping I may outstrip him - avoid the compromises, the mistakes, the sellouts he has made. I think that, however wary, he is glad about the idealism which seeps into a liberal education, and even about some of the social rebellion this idealism dictates.

I think Dartmouth should aim to graduate men who do not easily "adapt to their social environment," but who scorn the hypocrisy which seems to go along with "finding your niche."

Maybe the College's ideal should be the Angry Man who, as Whitman put it, sounds his "barbaric yawp over the roofs of the world."

The juniors go first in the tradition of running the gauntlet at Wet Down

The first pair saws furiously ...

passes the crosscut along .. .

then weights the log ...

until the second pair finishes ...

and the third takes over .. .

and finally joins the post-mortem.

With the campus recalling Eleazar's day, a member of the Dartmouth team, whichfinished third behind Maine and Middlebury, gives his all in the wood-chopping event.

There's always a dog in the act

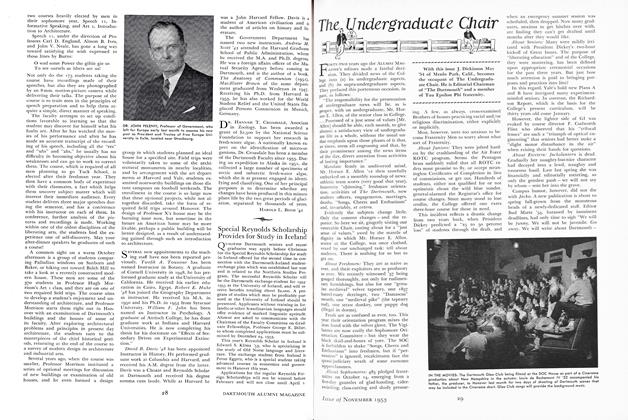

With this month's issue Dick May '54 ends his occupancy of The Undergraduate Chair. His final article embodies some of the ideas he expressed in a series of editorials written this past winter as Editorial Chairman of The Dartmouth.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

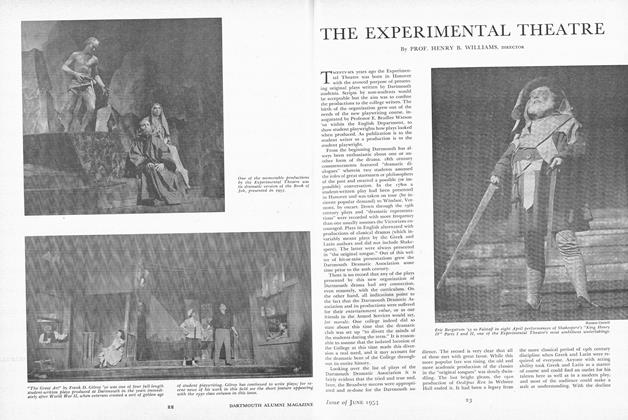

FeatureTHE EXPERIMENTAL THEATRE

June 1954 By HENRY B. WILLIAMS -

Feature

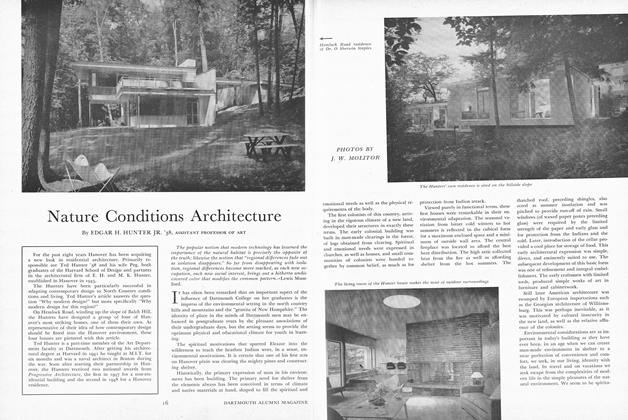

FeatureNature Conditions Architecture

June 1954 By EDGAR H. HUNTER JR. '38, -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

June 1954 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

June 1954 By HERBERT H. HARWOOD, ANDREW J. O'CONNOR, Richard Eberhart '26 -

Article

ArticleThe Faculty

June 1954 By HAROLD L. BOND '42 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1905

June 1954 By GEORGE W. PUTNAM, FLETCHER A. HATCH

DICK MAY '54

-

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

November 1953 By Dick May '54 -

Article

ArticleMilestones

January 1954 By DICK MAY '54 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

February 1954 By DICK MAY '54 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

March 1954 By DICK MAY '54 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

April 1954 By DICK MAY '54 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

May 1954 By DICK MAY '54