I APPRECIATE deeply the honor that has been conferred upon me here today. You have been most generous in welcoming into the Dartmouth family with such high honor this graduate of Harvard.

My admiration for Dartmouth is deep and long standing. It has been strengthened in recent years through my acquaintance with and respect for many men whose characters were largely formed here on this campus.

I would like to share with two sons of Dartmouth, my friends, Beardsley Ruml and Lester Granger - fellow members of the National Citizens Commission - the generous things said here about our common effort for the public schools.

Last year my predecessor on this historic platform spoke words heard around the world when he asked the Class of 1953 to stand with him against "the Book Burners." President Eisenhower spoke, too, in equally serious terms of having fun in life - fun in shooting a good game of golf, or in helping someone along the road, and later fun and joy and satisfaction when, as the leaders you are bound to , be, you help to solve some of the tough, human problems of our time.

It is in that same spirit that I would like to put before you for your consideration now and possible action later one of the great human challenges of our day. It is the problem of the proper education of our youth — of the 30 million youngsters in this country who are crowding up a shaky educational ladder right below you in our public high schools, elementary schools and kindergartens. A reservoir of 19 million pre-school age children and the continuing high birth rate guarantee that a present crisis which exists in our schools will be intensified in the years immediately ahead.

This is one of the most urgent problems facing the country. But I ask no more of you at this time than your consideration of it as a future priority for whatever help you may want to give to your fellow men and your country.

In golf I understand there is a form of stroke handicap called the bisque. The bisque can be taken at whatever point in the game the player feels it will do him the most good towards a winning match.

What I am about to suggest may be heresy even to my own cause. But I recognize that in regard to the myriad of problems with which you must eventually and inevitably be concerned as citizens, you will probably want to take your bisque right now to settle some pressing problems of your own. For example: the Army, postgraduate studies, a first job, a family, perhaps even the girl you are going to join right after this program. These are immediate human, personal concerns which I hope will make the next few years fly by for you with joy and satisfaction.

It is for a later priority of your interest then that I put before you in briefest outline some of the problems confronting our public schools.

I ask your consideration of these problems, not for the reason that you have a personal obligation toward education - although of course you have - but because it is an area which requires above all the help and support of educated men and women.

Here is a problem which has not yet made the front-page headlines. But the events of the postwar years have put it into sharper and sharper focus. It is becoming increasingly obvious that our educational effort, although it is of unprecedented size and scope, is far from commensurate with the needs and responsibilities of our times.

LAST fall in his welcoming address at the opening of College, President Dickey made this observation:

"As a nation we have never lacked the courage, the conviction and the resources to be strong, and in the past our security could be measured by our strength. National security in such terms was a relatively simple straight-forward kind of thing. But in this riven world where destructive power on both sides is now measured in astronomical terms, the old concepts of security through greater strength may already have lost much of their relevance."

President Dickey called for the maturity of a liberating education as the factor which can best help the nation. He said: "Nothing within the power of man is more important today than the measure of maturity which Americans can contribute to their national character."

As I am sure President Dickey would agree, this maturity must come from the whole process of education - from the kind of education which 40 million youngsters now in our lower schools should be getting. And as I see it, it is not just a case of developing the men and women who will lead the nation. Our ability to cope with the difficult and dangerous period in which we are living must come from the education of all our people - from an educational experience which will carry the talents of all of them to their fullest potentials.

As a nation we have an unwritten commitment to do just this in so far as public education can do it. We made this commitment in the early years of this century. It was then that the realization grew that the simple basic training which had been provided in our public schools in the 19th century, while good enough for the relatively simple and uncomplicated life of that period in our history, would not be enough for the American citizen of our century.

So during the first half of this century we accepted a commitment to provide full and equal educational opportunity to all American youngsters through the high school years.

What has happened in equalizing educational opportunity in this country in my lifetime is truly remarkable and wonderful.

I entered the Boston Public Latin School in 1913. I now find that I was but one of 8 percent of my age group in the U.S. who entered a secondary public or private school that year.

Today 80 percent of the high school age boys and girls are entering a secondary public or private school.

Consider the effect on our colleges.

In 1917 I was one of some 250,000 youngsters in college. As you know, this compares with 2,250,000 today. In qualitative terms this is universal education such as the world has never seen before. It is an accomplishment of which we can be proud. But we have not kept pace, in our support, with the demands of universal public education. The growing deficit in both the quantity and quality of education we are prepared to provide in the face of the demands and the need of our times has now reached alarming proportions.

Since the war, the increase in three, four and five children families has confounded the census experts and our school boards. Since 1946, nine million youngsters have been added to our school rolls, and each year for at least the next six years the schools will have to handle a million more than they handled the year before. Starting in 1956, our high schools will feel the real brunt of this onslaught and after that, our colleges.

Already in our public schools we have a deficit of 345,000 classrooms - that means ten million children are on half sessions. Including the backlog, the total classrooms needed by 1960 will be 750,000. (The cost to build these schools is 26 billion dollars.)

Right now we have a deficit of 70,000 qualified teachers - a deficit which will mount at the rate of 100,000 a year from here out at the present low rate of new teachers in training and the high rate of teachers leaving the profession.

Meanwhile, criticism of the schools, much of it justified but most of it based on inadequate knowledge of how and what they are teaching, is - in many communities - delaying action needed to meet the essential physical needs and to support improved educational programs.

As a people we believe wholeheartedly in education, but we have not, as a nation, found the will to support our educational effort as we have, for example, our program of national defense.

The problem of the schools is a national problem. But it cannot be solved, like our defense problem, by action of the Government at Washington.

Our schools are state and community responsibilities. Their standards must be set by the citizens in the individual state and local school districts.

There are 65,000 such districts. At least 65,000 determined citizen leaders are needed in those school districts to lend a hand to the youngsters who otherwise will be getting a second-rate education to prepare them for their responsibilities in the leading nation of the world.

As Lester Granger has declared:

"Local control of the schools connotes local responsibility, and the same community that insists upon determining the philosophy and objectives of its school system must accept the responsibility for providing and protecting decent standards of public education. Too many Americans in this matter of guarding the interests of our public schools are content to 'let George do it'— not realizing that 'George' died several decades ago."

In the last few years in some ten thousand communities good citizens have heeded Mr. Granger's sound counsel.

They have organized themselves in a new kind of unofficial, extra-legal, voluntary council of citizens to study the school problems of their communities and to work with the school people to strengthen their local schools.

Through these groups the rising interest and concern of citizens is being channeled into constructive, helpful actions designed to solve the special local school problems of their communities.

This is the most heartening development on the current educational scene.

It is hard to evaluate the results which these voluntary citizens groups are achieving for their schools. Their achievements must be measured against fantastically expanding school needs.

The most outstanding achievement has been the new climate which has been created - a climate for school development which combines interest with a willingness to accept new solutions for the schools' tremendous new problem.

Is the pay scale for our teachers the chief reason we are losing so many of our best teachers, and why enough able youngsters are not entering the profession?

In Ladue, Missouri, the community is supporting a salary plan which will take its best elementary teachers up to a salary of $10,000 a year. That is a challenge, not only to every community in Missouri - but to our communities everywhere.

How can we encourage more graduates of our liberal arts colleges to teach in public elementary schools?

Today several of our liberal arts colleges, with Foundation aid, are offering graduates a year's internship as practice teachers in neighboring public schools. After the year which includes seminars in Education Studies, they are qualified for professional teaching.

Can we make more efficient use of the teachers we have in the face of our painfully inadequate supply? Can we supplement our trained teachers with untrained helpers?

In Michigan and Connecticut, communities are supporting experiments in the use of untrained teacher aides. In classrooms of 45 children, the assistant relieves the professional teacher of many time-taking tasks. In two such classrooms which I visited in the Bay City, Michigan schools it seemed to me that the youngsters are getting more personal attention and teaching than under the conventional arrangement. This experiment holds real promise for supplementing the teacher supply.

Today more and more communities are avoiding a yearly school budget crisis by planning their school programs on a five or six-year basis. They are studying their future educational needs in terms of both quantity and quality in close cooperation with their school officials.

These are some of the immediate solutions that citizens across the country are working out. But a more long-range solution is required, and it must involve an entire new concept of our educational responsibilities and goals. We must think in much larger terms, both in financing the schools and in measuring our educational expectations.

Financially, we must find the way to match in our support of our community schools the same high levels we are establishing for our personal and family standards of living. Walter Lippmann, in a recent address, called for a complete resetting of our educational sights. He said:

"It cannot be denied that our educational effort is inadequate. I do not mean that we are doing a little too little; I mean that we are doing much too little. We have to do in the educational system something very like what we have done in the military establishment during the past fifteen years. We have to make a break-through to a radically higher and broader conception of what is needed and of what can be done. Our educational effort today, what we think we can afford, what we think we can do, how we feel entitled to treat our schools and our teachers—all of that—is still in approximately the same position as was the military effort of this country before Pearl Harbor."

Beardsley Ruml, speaking from the same platform was more specific. He felt that the financial needs of our schools were so urgent that the time had come to tap the resources of our Federal income tax. Pointing with confidence to the ever-increasing productivity of our country, he declared that the future great needs of our schools are not large when projected against the tangible realities of future increased national income. The problem, he felt, was how to allocate a small percentage of the increase to public education without Federal control or dominance of the local schools. He called for Federal grants-in-aid on a per capita child-in-school basis, subject only to a certificate of proper state authority that the funds had been received and spent for education under concepts and supervision legally specified by the state. Such a solution, Mr. Ruml believes, would prevent the dangers of intervention in school affairs by the Federal Government and keep the basic control and responsibility where it belongs—in the states and local communities.

So, in this and other ways, outstanding citizens are contributing fresh thinking to the whole educational picture. In countless communities they are rediscovering their schools and lending their generous support to what the schools are trying to do. At a time when all our educational institutions are subject to attack, I find a statement made by the community leaders of Scarsdale, New York, particularly heart`ening and inspiring. The statement was made in response to the attempt of a few men to have removed from the school library books which they charged were subversive and unfit for young minds. One of the leaders of the committee of citizens which rejected this attack and defended the Scarsdale schools was Dartmouth Trustee Sigurd Larmon. Said the Committee:

"We do not minimize the dangers of Communist and Fascist indoctrination, but we want to meet these dangers in the American way. A state that fears to permit the expression of views alternative to those held by the majority is a state that does not trust itself.

"Of course there are risks involved in allowing young persons relatively free access to a wide range of reading material. But we believe that there are greater risks in any alternative procedure. Surely we have not, as a people, lost the courage to take the risks that are necessary for the preservation of freedom.

"We have confidence in the young people of Scarsdale. We believe that they have the sense and the balance to develop for themselves, in a world of free ideas, a set of democratic principles which will enable them to meet the changing problems of the future."

The disputed books .were not removed from the Scarsdale school library.

The job of building a strong school system is a continuing one, and it will not be done in five years or in ten. There is no easy panacea. Indeed, the school crisis will very probably be at its height at about the time that the first children of the Class of 1954 are ready for school. I put the problem before you, not simply as future parents and not simply because your own superior educational opportunity has given you a special responsibility in this connection. These reasons are valid and compelling ones, but beyond them is the additional reason that the schools desperately need in our local communities and at the national level the understanding and talents with which an outstanding liberal education has provided you. Here is an area in which you can contribute directly to building the strength of your country by raising the level of all of the citizens in whose hands its future will rest.

There is my appeal for your future help. Meanwhile, whether your first concerns are the Army, postgraduate studies, a first job, or a family, I wish you all the best of luck. May these next few years bring you much joy and satisfaction—and fun.

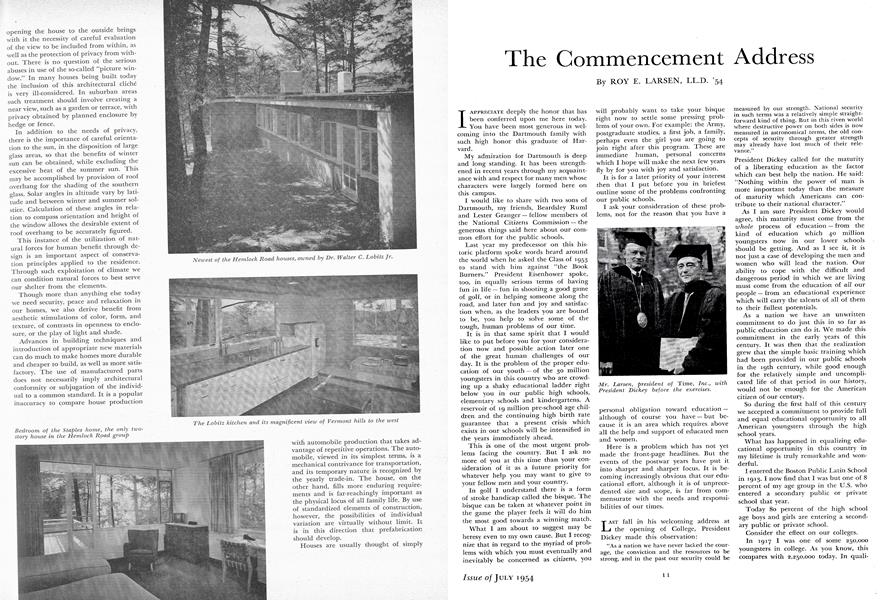

Mr. Larsen, president of Time, Inc., withPresident Dickey before the exercises.

Ensigns being sworn during ROTC graduation in the Bema Saturday morning

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeaturePresident Emeritus Hopkins Is Honored With Dartmouth's First Alumni Award

July 1954 -

Feature

FeatureRobert S. Oelman '31 Heads Alumni Council for 1954-55

July 1954 -

Feature

FeatureE. S. French Retires as Life Trustee; Ruml Succeeds Him

July 1954 -

Feature

FeatureAnother Record for the Fund

July 1954 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929's Record-Breaking 25th

July 1954 By CHRISTIAN E. BORN '29, BILL ANDRES, SQUEEK. -

Article

ArticleThe 1954 Commencement

July 1954 By FRANK PEMBERTON

Article

-

Article

ArticleAbout the Author:

February 1958 -

Article

ArticleThe Distinguished Young Alumni Awards

SEPTEMBER 1991 -

Article

ArticleLEDYARD CANOE CLUB

MAY 1968 By ALBERT C. JONES '66 -

Article

ArticleThayer School

January 1954 By ED BROWN '35 -

Article

ArticleJOHN WHEELOCK'S EUROPEAN JOURNEY

January 1933 By Leon B. Richardson -

Article

ArticleMedical School

March 1942 By Rolf C. Syvertsen M'22