AFTER four years, we are here to acknowledge that 550 horses have been, brought to the trough. We are here to ask whether or not we have taken a big enough drink from that trough. Surely our answer must be based first on a knowledge of what we were supposed to drink.

We are told that we have been here to acquire the power to think through solutions to issues which harass us: international issues like "How do we proceed with the Soviet?"; personal issues like "Should I transcend reason and have faith in God?" We are told that we have spent $8,000 in order to learn bow we can define the alternative solutions to issues like these, choose between the alternatives and then act upon the basis of our choice. College, we are told, is a place where men learn to think. This fall it was a place where six out of the first eight speakers in the Great Issues Course said, "My generation has failed to think through to an answer. Now the search becomes your task." For the past four years, it has been a place where we have found too many unanswered but pressing issues, a place where we have come to fear that the majority are unanswerable, a place where we have, consequently, begun to doubt our ability to answer any.

Yet the by-word stands unmolested. Still we are told that the purpose of college is training in thought. We shall become thinking men. Therefore, we are told, we shall be decisive men, potent men, men who define, choose and act. You know, though, when you look at the facts, the situation doesn't look quite so pat. Take statistics on 700 men who graduated ten years ago. They think adequately enough, but their potency is open to serious question. Thirty per cent of them are still unmarried. Among all 700 there's only one brewery owner and one man with a mistress. With all due respect to Mr. Larsen, who publishes Time magazine, what can only be considered the most telling sign of impotency - 84 per cent of that class votes Republican. Perhaps all this sterility can be explained by the fact that the 700 men graduated - from Princeton.

Seriously, though, it appears that college must do more than teach men to think. If our chief claim at the end of four years is that we have become rational, then we have taken far too short a drink from the trough.

Thinking men are not necessarily potent men because rationality is easily weakened and subverted by the frantic cry of pressing need. It is only if men's thinking is at all times channeled and directed that they acquire potency - the power of a man to exert some control over his own destiny. Men who think to act in accordance with what to them is ultimately good, true and valuable - these are potent men. They forever use their rationality in order to choose between alternative solutions to an issue in the light of their ultimate concern. It is this knowledge of what is ultimately worth fighting for, which we must have drunk - and drunk deeply - from the trough.

Little can be said about the nature of ultimate values. A man becomes an individual; he becomes more than a statistic in a Gallup Poll, more than an integer with a home, a car and golf on Saturday, when he arises to say, "This to me is ultimately true." Then he has purpose. Then he is fulfilling himself in the highest reaches of human possibility. He will be ready to sacrifice for something greater than himself. Consequently he will be potent. Keep in mind, though, that what he declares to be ultimately valuable for himself must necessarily be unique; each man's choice must be different. If I tell you my ultimate values and you say that henceforth these shall be yours, then you are a mimic, not a man fulfilling himself. That is why little can be said about the specific nature of ultimate values. But there are two guideposts which a man can use in deciding, two signs which point the way.

THE first is this: If a value or a goal is ultimate it is not attainable. Seventy years ago Mr. Justice Holmes said that a man must "learn to lay his course by a star he has never seen. He must learn to dig by the divining rod for springs he can never reach." This is the disconcerting truth. If you know that someday you will be able to grasp that for which you now sacrifice, then it is not absolutely ultimate. The overriding horror of Communism and Fascism is precisely that their ultimate values are not ultimate at all. The Fascist wishes only the maximum expression of man's desire to dominate and crush, the maximum expression of will-to-power. The Communist symbol is a full stomach. From each according to his ability. To each according to the size of his maw. These are not ultimate values. They are attainable. They are merely soothing balms to the terrible press of current necessity. It is the limitations of these balms, Pope Pius XII said last Christmas, which results in the deep anguish of contemporary man, made blind for willfully surrounding himself with darkness, cast irrevocably into perdition by his own foolhardy attempt to constrict the possibilities of his soul.

This is the first guidepost, the first sign which points a man towards ultimate values. They must be unattainable. Now, what is the second guidepost? Put it this way: If an ultimate value is valid for man it must take into account his nature. It must not be so unattainable that he cannot even begin to work towards it. For example, if you do not believe that men can exert self-control, then you cannot erect liberty, equality and fraternity as the ultimate values for which you will strive. Freedom, equality, brotherhood - these are meaningless rights; indeed they become fetters unless men by and large are capable of controlling themselves. Similarly, if you do not believe that man was created by, that he is now judged by, that someday he will be redeemed by Almighty God, then you cannot govern yourself according to the ultimate values of faith, hope and love. You cannot partake of the Christian spirit. And you know, if the most important question you can ask a man is "Are you now or have you ever been . . .," then your ultimate purpose is the deification of Joe McCarthy. When you come to think about it - that's not so ultimate after all.

These, then, are the two guideposts which point the way to ultimate values. The trip is an individual one - and a lonely one. It is fraught with uncertainty and pitted with despair. But in the end every man must have his dogma. No man can be completely free. He must be bound by the truths which he considers ultimately worthwhile. If he has no such truths, then he is a hollow man, then, like Arthur Miller's Willy Loman, he will be riding out there in the blue on a smile and a shoeshine and when people don't smile back, that will be an earthquake. Like Willy he will die the death of a salesman, the death of a man with no inward strength. He has no individuality. His every action is determined by the whims of people around him.

The most dangerous flaw in people like Willy is that they look for help from outside. They can't trust themselves. There's nothing inside them - no strength. So when something goes wrong, they look outside to find the trouble. When their marriages crack up, they blame divorce laws, or low wages or in-laws. They don't try to find out what's lacking inside. They have no insides, no hard-bed of ultimate values in the light of which they think and act. A man like Willy Loman is a man who finds no one home when he comes knocking at the door of himself. He's the radar man - the man who thinks what the fellow next door thinks. And when something goes amiss, he blames it all on that fellow next door or the weather or the government.

WE acknowledge here today that we have been brought to the trough. Have we drunk deeply enough to say, each to ourselves, that we are not Willy Lomans? If we have it is because a man between the ages of 18 and 22 suddenly discovers that he cannot live like the Willies. He therefore makes the most of an opportunity to sit at the feet of professors who break the bounds of their own disciplines in order to integrate the material of many fields. Even if such professors "cease to be honored in our memories, they will continue to be unwittingly honored in our lives." For a man must arrive at his dogma byway of integration - not departmentalization. The professor who points the way to integration is the true Liberal Arts professor - the giant who breeds men.

Similarly, the student with top grades in college offers no guarantee of like performance outside. If he has learned to think only in terms of specialization, if he has never integrated all his information in order to search for dogmas which are relative to his whole life, then he will be unable to enter the flux of things. He will be adept only in that celebrated shaft of scholarly stone - the Ivy Tower — not in the world of men.

Five weeks ago, Dr. Paul Tillich told a reporter from The Dartmouth that "the acts of a man in a particular situation depend upon his ultimate concern." That sums up what I have been saying. Perhaps it also points to the difference between valedictorians and men who've been out in the world a while. What it has taken me six pages to say, Dr. Tillich managed in 14 words.

If we have drunk deeply enough from the trough, we shall henceforth think, we shall always live in the light of what is ultimately valuable. In the end every man comes to terms with life as a whole. He is forced to act out the demands of an overall concern. In the past four years of freedom from the need to feed and clothe ourselves, we must have acquired the power to think in terms of such concern. If we have failed, then count on it - the dryness of our throats will first choke off our individuality and then our way of life. For as Emerson says, Democracy exists in the individual soul - not in the polling place.

Let each one of us remember that what the Liberal Arts College must turn out is men whose finest attribute is not necessarily the ability to conceive a better farm program or lessen international tension, but men who think and solve problems in the context of something broader and deeper than their home, their job, their college, their nation. The men who leave this college must operate in the context of true individuality which is the source of any finer destiny for themselves and all other men. They must wear their hearts out after the unattainable.

We, each one of us, must ask now, "Have I drunk this deeply ?"

Milton S. Kramer, former editor of The Dartmouth, delivering the 1934 valedictory.

The two oldest graduates attending the Alumni Association meeting June 12 were Joseph S. Matthews '84 (left) of Concord, N. H., and Henry H. Austin '85 of Warner, N. H.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeaturePresident Emeritus Hopkins Is Honored With Dartmouth's First Alumni Award

July 1954 -

Feature

FeatureRobert S. Oelman '31 Heads Alumni Council for 1954-55

July 1954 -

Feature

FeatureE. S. French Retires as Life Trustee; Ruml Succeeds Him

July 1954 -

Feature

FeatureAnother Record for the Fund

July 1954 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929's Record-Breaking 25th

July 1954 By CHRISTIAN E. BORN '29, BILL ANDRES, SQUEEK. -

Article

ArticleThe 1954 Commencement

July 1954 By FRANK PEMBERTON

Article

-

Article

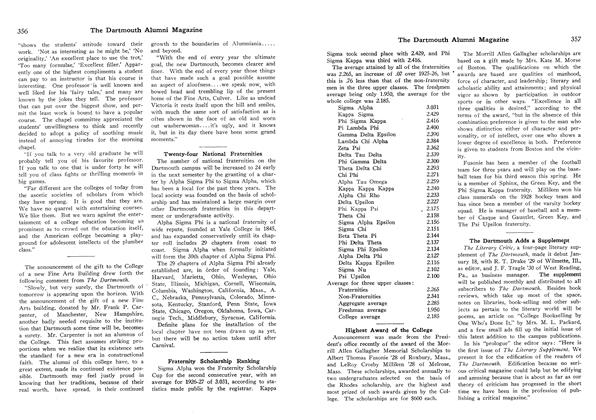

ArticleHighest Award of the College

FEBRUARY, 1928 -

Article

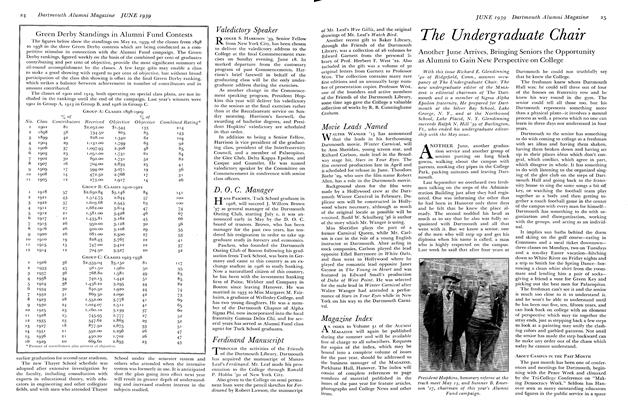

ArticleGreen Derby Standings in Alumni Fund Contests

June 1939 -

Article

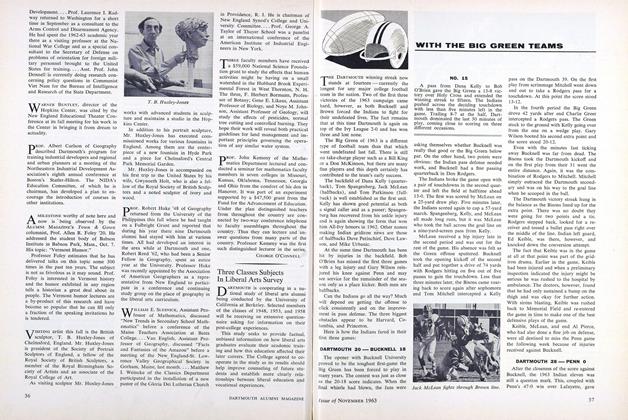

ArticleThree Classes Subjects In Liberal Arts Survey

NOVEMBER 1963 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Authors

JANUARY/FEBRUARY • 1987 -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

March 1993 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

ArticleWith the Players

March 1938 By Sidney B. Cardozo Jr. '38