THE University of Oxford is an elusive, mystical creation not easily discernible at first sight. Apart from the Bodleian Library, Sheldonian Theatre, University Museum and a few playing fields, the University seems almost a myth. Certainly there is no campus, often a disappointment to American visitors. Oxford, with the exception of that other university - Cambridge, stands unique in the relationship of its colleges to the University.

Oxford's twenty-six colleges, each having an enrollment of from 160 to 450, are with a few exceptions completely autonomous. They have different policies, administrative organizations, facilities, resources and personalities. Although the methods and customs, and hence the undergraduate life at each of the colleges, are basically similar, there is no doubt but that each college leaves its impression on its graduates. It is interesting to note for instance that Christ Church College has among its graduates eleven English Prime Ministers, with Sir Anthony Eden a prospective twelfth. New College (new in 1375!) of comparable antiquity and renown hasn't produced a single Prime Minister for the realm but has consistently supplied graduates who have achieved distinction in the Civil Service, and this result isn't due to any conscious admission policy. When the Duke of Windsor, as Crown Prince, attended Oxford, he was at Magdalen College where life is luxurious, pleasant and very subdued, in keeping with the superb physical surroundings of the college. Balliol is the home of scholasticism - at least during the last fifty years Balliol men have achieved wide scholastic recognition during and beyond undergraduate years. At one time no less than seven Heads of Oxford colleges were former members of Balliol. Brasenose has always had what one historian has described as a "marked, but not exclusive predilection for the exercises and amusements of out-door life and a spirit which leads men to do what they are doing with all their might, to undergo training and discipline for the sake of the college, and hang together like a cluster of bees in view of a common object." And so it goes with all of the colleges. The colleges are Oxford University and their individual quads are the "campus" of the University.

The average Oxford student is better educated than his counterpart in American universities. On second thought that is a little misleading for it would be very difficult to select an American counterpart to the Oxford or Cambridge student. These two universities have held and do still hold a very superior position in the hierarchy of English universities, and are the recognized goal of every English child. And child is not an exaggeration for at the age of eleven every publicly educated student is given an examination to determine his or her aptitude for university training. Subsequently the children are divided into three groups attending separate and distinct schools: one group receives vocational training, another group is given a general preparatory course and the third section begins a university preparatory program. Of course the private schools (or public schools as they curiously are called in England) are outside this classification. Without going into the details of this system and the English argument for justification, it is apparent that a student primed since the age of eleven will be well educated and capable of advanced work. Add to this the fact that the cream is again scooped from the cream because of the recognized superiority of England's traditional universities and you can imagine that in general the intellectual calibre of the English student at Oxford is quite exceptional.

I wouldn't care to compare the average English student at Oxford with his mythical American counterpart in one of two mythical American universities. I'm inclined to believe the comparison would be favorable but it would be a task for no less than Mr. Gallup. I emphasize English students at Oxford because Oxford has a very large percentage of foreign students, particularly if you include within that category other members of the Commonwealth. Oxford is prejudice free, which accounts for the fact that it probably is the nearest approach we have today to an international university. Outstanding students from throughout the world are spread among the colleges and they take a very active role in all phases of collegiate and university life. For example, Jack Buchanan '53, a Dartmouth Reynolds Scholar studying Russian at Exeter College, was selected this year to row in a trial eight. Of the sixteen men so selected only six were Englishmen. Only six of my rugby teammates were English. And in the various clubs and student organizations foreign students play a predominant role.

Instruction at Oxford is based on the tutorial system. A man has at least one tutorial each week; the men are taken by the tutor singly or in pairs. One or both men will have written essays, which will be read. The proceedings are quite informal and are more a discussion than a lesson. A recent witty critic of Oxford, asked how the tutor conveys his instruction to his pupil, replied, "He smokes at him"; the answer suggests both the intimacy of the tutorial and the meditative character of the tutor's criticism.

A personal relationship is established between the undergraduate and his tutor which ordinarily develops into one of real friendship. The tutor - or don as he is more commonly called - is a friendly adviser on all matters, and it is a wellestablished custom that if the undergraduate gets into trouble his don will act as the counsel for defense in any discussion with the college or University officials. The colleges ordinarily have several tutors in each field and consequently during the course of an undergraduate's three-year residence his supervision is divided among these tutors, always, however, with one man being primarily responsible for his progress and preparation for the ultimate goal - "Schools," the University degree examinations. Periodically the tutor will set examinations for his students which have no official bearing on the student's standing but are of mutual benefit in assessing the student's progress and preparation.

The tutorial system depends to a large extent on the personal character and calibre of the tutor. Fortunately the tutors I've had at Brasenose have been both stimulating and well informed but such isn't always the case. Several Rhodes Scholars have told me they've been disappointed with their assigned tutors. Changing colleges is out of the question and a change of tutors is practically impossible so the selection of a college is vital.

Lectures are, with a few notable exceptions, quite mediocre and are in general poorly attended. Attendance is purely optional and a large proportion of students prefer to spend that time in individual study and research.

The keen sense of competition and urgency that exists in American universities is notably absent at Oxford, due largely to the fact that there are only two examinations of record and importance during the three-year undergraduate period. The Oxford system probably is the pedagogical ideal but its effectiveness is entirely dependent upon the initiative of the student and the capability of the assigned tutors.

Athletics

IN the afternoons from 2 to 5 almost all Oxford students are engaged in some form of outdoor activity. Each of the twenty-six colleges has its own playing fields, tennis courts and boat houses (more often simply large barges moored permanently to the banks of the Isis). The colleges have at least two teams in the more popular sports of rugby, cricket, soccer and tennis. Most of the colleges have track, golf, field hockey and squash teams too. However, rowing creates the most interest and is the most universally supported. Some of the colleges have as many as eight different crews. In fact, last year after our college rugby season was over, a "rugger boat" was organized. Few of the men had had any experience whatsoever but we were tabbed as probably the most powerful boat on the Thames. Our average weight was thirteen stone three pounds (185 pounds), which by Oxford college standards was rather phenomenal. We were considered so well coordinated and efficient that there was some question whether or not we should be given oars. We subsequently proved ourselves by breaking three oars!

For the colleges the big event of the year - The Winter Carnival, so to speak - is Eights Week. For four days crew races are held and academic life virtually ceases. The period of training and preparation for these races is intense even though it is practically impossible to "win the race" during Eights Week. Because the River Isis is so narrow the crews must race in single file. I'm not sure whether the race was instituted before the stop-watch or whether the English vetoed the "elapsed time" idea because of a dislike for its mechanical nature. At any rate, the races are run single file, each boat starting from the Dank with a uniform distance between boats. As the starting gun is fired each crew strokes furiously in an attempt to catch the boat ahead and to avoid being caught by the boat behind. A boat is caught when it is bumped - literally bumped. The coxswain strokes his crew until the bow of his shell overlaps the stern of the preceding shell; when he is confident there is an overlap he jams the rudder so that the bow and stern bump. The bumped shell pulls off the course and the "bumper" continues in an effort to do the near impossible - overbump or catch a boat originally two positions ahead.

The course is one and a half miles in length and the footpath adjacent to the course is filled with supporters, running on foot shouting encouragement and warnings of any approaching bumps. An elaborate set of signals is worked out between the coxswain and an official observer, also on foot, which is transmitted via shots from a blank pistol. Eights Week is a startling revelation to those who have been led to expect traditional and unshakeable English reserve. If a crew is outstanding it may make as many as six bumps in the course of Eights Week. The race is rowed for four days and the boats which have bumped exchange places for the following day's race. Each college starts the first of the four days' races in the position in which it finished the previous year. Thus to reach the "Head of the River" requires a consistent and sustained effort by successive groups of undergraduates. To finish Eights in first place and to hold the cup symbolic of that top position is probably the proudest achievement in the world of sport for an Oxford college.

The annual boat race against Cambridge over a course of four and a quarter miles is one of the great English national festivals. It is watched by over 500,000 people who line the banks of the Thames near London.

Rugby football also creates a good deal of interest. The colleges have a series of matches culminating in an elimination competition; the final rounds attract three or four thousand spectators. On the University level the rugby training and preparation are on a much more formal basis. The captain, who is also the coach, selects his varsity group from among the 800 men who play on the college teams. A series of "trials" are held for the purpose of comparing and evaluating these candidates; these games are easily organized because rugby is a spontaneous game with few predetermined plays. The "trials are well attended and the speculation runs high concerning the team that eventually will represent the University in THE MATCH (Oxford v. Cambridge).

The boys referred to our captain this year, an outstanding South African International player, affectionately but appropriately as "The Deity." During the season he had his hands full for in addition to the varsity team there were two other teams playing regular schedules. The captain experimented with these groups until the week before the Varsity Match with Cambridge when the final team was announced. Fifteen men are selected, there are no substitutes in the game. In fact, in one of our games last fall, due to injuries the entire second half was played with only thirteen men. This no substitution rule is convenient in a number of respects; large travelling squads are unnecessary and it is much easier to arrange an informal game which satisfies all the participants. However, in an important game there is a temptation for a man to remain playing when there is risk of an aggravated injury. The English say there is little danger of serious injury and in contrast to American football this is true. Blocking (obstruction, as it is called) is strictly prohibited and consequently there is much less body contact than in football. First-class rugby is more tiring than American football because it is almost a constant eighty-minute run (a five-minute break at half-time!). However, bruises and sprains are considerably less frequent than in our game.

In view of the fact that American football is essentially a variety of rugby as adopted at Harvard and Yale in 1875, people have asked which game I prefer. That's a difficult question to answer because no sport or game is an end in itself. The experiences and companionship that football provided at Dartmouth are incomparable. Memories of Tuss at a Harvard half-time when we were down twenty points and went back on to win; of pushing Johnny Dell on a blocking sled all over Chase Field while he politely requested more diligent labor; or of looking up and down our line during a goal-line stand (of which we had a goodly number in 1951, as I recollect) and wondering where the opposing ball carrier would hit next; these and many other memories convince me that in a choice between Dartmouth football and Oxford rugby it would be Dartmouth football all the way. But if someone were to call me up and ask me to play either an American football game or a rugby match on Saturday, and often such a rugby "scratch" side is so organized, I wouldn't hesitate a moment before choosing rugby. This' may be due largely to the fact that I was a lineman throughout my football career and although a good solid tackle or a key block which gets a ball carrier away is certainly a satisfaction, in any ball game the natural desire is to handle the ball and play a material role in its advance.

For example, whenever Johnny Dell wanted to give the linemen a break or a treat, he'd let us strip off our pads and play twenty minutes or so of touch football. I don't remember that any undiscovered halfbacks came to light but it certainly was a refreshing contrast. Then again in 1949 when we had such a successful day against Princeton in Palmer Stadium, Jon Jenkins, our All-League tackle, achieved what he called his "lifelong ambition." I believe it was in the last play of the game, a conversion attempt, that he was given the ball for a "tackle plunge." As it proved Jon hadn't been miscast as a tackle but that particular conversion must be one of his favorite recollections of Dartmouth football. In rugby, on the other hand, each man knows that if he has the stamina and the sense to be in the right place at the right time, he'll take part in the "movement." Rugby, despite an uphill climb, has become increasingly popular at Dartmouth in recent years. I'm not advocating rugger for football in the Yale Bowl next October but I do approve of the support the College is giving it.

One of the appealing features of making a University team is the prospect of vacation touring. Most of the major teams organize vacation tours which are expense free and provide memorable experiences. Because of the international nature of most English games and sports, the opportunities are unlimited. This spring a combined Oxford-Cambridge Rugby Team is touring California and Canada. Last year the cricket team toured Denmark; the crew, Sweden, and the soccer team, Ireland. The Cambridge crew went to Japan and their cricket team to South Africa.

Other Diversions

THE jokes about women "undergraduettes" are legion and many of the undergraduates look to the nurses' training schools and the many continental visitors learning English in Oxford, for feminine companionship. Without additional comment, I prefer Smith. There is an infinite number of clubs and societies which students may join and in addition to the college clubs there are University groups. Their primary purpose is to gather men of the same interests and to provide distinguished men as speakers. Eminent personalities are very generous in accepting these invitations and submitting to the inevitable question periods. Most of the Oxford clubs are of this passive variety and there are few organizations with a definite purpose providing activity for the members. This passive interest is also reflected in the lack of student government on college and University levels. There are many musical societies but probably the most famous of the Oxford organizations is the Union which serves the double purpose of a club and a debating society. It has its own building and grounds and the debating hall forms a wing by itself. The Union is constructed on the parliamentary model and the weekly debates are parliamentary in plan and procedure. It has been called the training ground of British statesmen. The presidency is the highest of undergraduate honors. From an American point of view the speakers never "get down to facts"; however, the witty repartee and the sheer eloquence are highly entertaining.

But the Union hasn't had a monopoly on Oxford eloquence. Three Balliol undergraduates, Mr. Hilary Belloc, son of the famous Catholic writer, Mr. Henry Scrymgeour-Wedderburn, later Under Secretary of State for Scotland, and Mr. George Edinger, now successful in Fleet Street, some years ago decided that Freud was having it too much his own way. With wonderful subtlety and skill they established a wholly imaginary learned society, "The Home Counties Psychological Federation" and hired the Town Hall for a public lecture. The lecture was to be given by Dr. Emil Busch of the University of Tubingen, Germany, and Dr. James Heythrop was to act as chairman and moderator. Busch was Edinger, Heythrop was Mr. Wedderburn. Mr. Belloc arranged the setting so that a sudden blackout and getaway, if necessary, could be managed.

The costumes and makeup were remarkable. Freud was very much the vogue and a large audience gathered which included two Heads of colleges. Dr. Heythrop made his introductory comments and amid hearty applause the "German savant" stood up to begin the address.

"Often, ladies and gentlemen," he said, "I tell Dr. Freud that the element of COaesthesia, which he is apt to overlook, coaesthesia I repeat, is an essential of psychoanalysis. Much that my colleagues ascribe to sex I would write down as the outcome of co-aesthesia. What, then, is co-aesthesia?" Dr. Busch then proceeded for fifty minutes to explain "personality overlaps" illustrated with cases in point. During the ques. tion period he defended his position well, at one point disarming a strong Freudian supporter's question with, "From Professor Freud I will not dissent. He is my very good friend. But of him I feel sometimes for the number of trees the wood he does not see." At this point Dr. Heythrop interrupted and reminded Dr. Busch of his train; signing autographs, bowing and accepting invitations he had no intention of keeping, Dr. Busch was escorted to the waiting taxi.

It was not long before London newspapers picked up the story and all Oxford laughed. One of the Heads, who had been completely taken in, when asked what he thought of the lecture, said, "It seemed all right but it was a little difficult to gather what it was all about."

An amusing practical joke occurred recently at one of the college eating halls. The undergraduates and the professors, dons and Head of the college all dine together. The faculty sit at the High Table and before the meal is served a rather lengthy Latin grace is recited. One of the students, perturbed at the delay, decided to lodge a protest. During the grace a curious noise broke out and continued throughout the recitation. There was no doubt what the noise was — an alarm clock. But where the noise came from was another matter. The Head had the entire assembly hunting for the cunningly concealed clock. Finally it was discovered over the doorway and a ladder had to be brought in to reach it. Needless to say, no one claimed the clock.

A story is told about a University proctor. The proctors are the ministers of admonition and correction. They stalk the streets in formal academic dress accompanied by their "bulldogs" - men in bowler hats, chosen for their speed in pursuing recalcitrant students. They maintain a complicated set of rules about motor cars, and are always on hand to see that behavior in the pubs does not extend beyond the bounds of gentlemanly conduct. During Eights Week they are very much in evidence.

This particular proctor is reputed to have been a very successful night climber. In fact, the story goes that he was the first to have successfully climbed the Radcliffe Camera, the Matterhorn of Oxford. This nocturnal pastime of climbing difficult buildings and monuments is a highly developed activity at Oxford and Cambridge. It is interesting to speculate as to its origin. It might stem from the fact that every undergraduate out after midnight must crawl up drainpipes and over walls into his college rooms. Midnight has been the traditional hour through the centuries for the closing of the college gates and despite the fact that "breaches" are the common knowledge of college and University officials, no alterations in a tradition of such antiquity could EVER be considered. The routes aren't very difficult and are relatively safe; the only problem arises when a man is a trifle inebriated. In that case he usually waits at the starting point for the next late comer and invokes his assistance. Add to this the fact that every Englishman seems to have an irrepressible urge to climb mountains, despite the total absence of anything in England faintly resembling a mountain, and it is only logical that he should turn to the most available substitute. They'd go wild in New York! The climbing has to be done at night because the authorities frown upon such sport (which adds a delightful piquancy not found in the Alps themselves), primarily because of the danger involved and secondly because of the damage such climbers have done to age-old memorials.

Oxford's Matterhorn is the 200-foot reading room known as the Radcliffe Camera. Though provided with such handholds as bulls'-eyes and decorative urns, it has a crucial point: a circular overhang which runs around the building. The assault is generally a two-man affair; when the overhang is reached, one serves as a human ladder for the second. At any rate, one night this proctor is supposed to have seen, halfway up the face of the Camera, two stealthful climbers. Going to the other side of the building he started up himself, reached the top before the climbers and there greeted them with, "Your names and colleges, please, gentlemen."

The building which really captures the imagination of the night climbers is Tom Tower which surmounts the Great Gate to Christ Church College. Great Tom, the bell in the tower, strikes out 101 strokes

every evening at five past nine, in memory of the 101 scholars at this college the year Sir Christopher Wren completed the tower and Great Tom was hung. Tom Tower never has been conquered because a smooth belt of stone broken only by the face of the great clock serves as an impasse. The theoretical answer is that the climber must get up to the clock by twenty-five minutes before two. He must then reach up and grasp the huge minute hand, which will in a quarter of an hour carry him to the point, ten minutes before the hour, where by chinning himself he can get a handhold and with support from the minute and hour hands achieve the summit. The fifteen minutes of dangling do present certain problems.

"Sconcing" is another quaint custom that exists in some of the colleges. It arises from the fact that there are certain rules as to what can or cannot be mentioned in conversation during dinner. If an undergraduate commits a faux pas he may be sconced by the senior undergraduate at his table. Either he must supply beverages for the whole table or he must chug-a-lug, i.e., drink with one breath a sconce holding three or four pints of liquid. The condemned man has the alternative of appealing to the High Table, where the faculty sits, but he must appeal in Latin, and if the Latin is poor, the sentence is not only confirmed but increased.

The many Dartmouth Oxonians will be disappointed that there has been no mention of the beautiful walks in the area, the swan colony (over 450 by latest census) on the Isis, the colorful degree ceremonies, the many inspiring spots of historical significance, High Street - considered by many to be the most beautiful street in the world, the many majestic spires, the cathedral, and the chapels that rise so serenely over the various colleges and University buildings, and so on ad infinitum. But I've already overstayed my welcome, it's almost 1:00 a.m. and I must meet a friend at Tom Tower for a little exercise. So if you'll excuse me,

Cheerio.

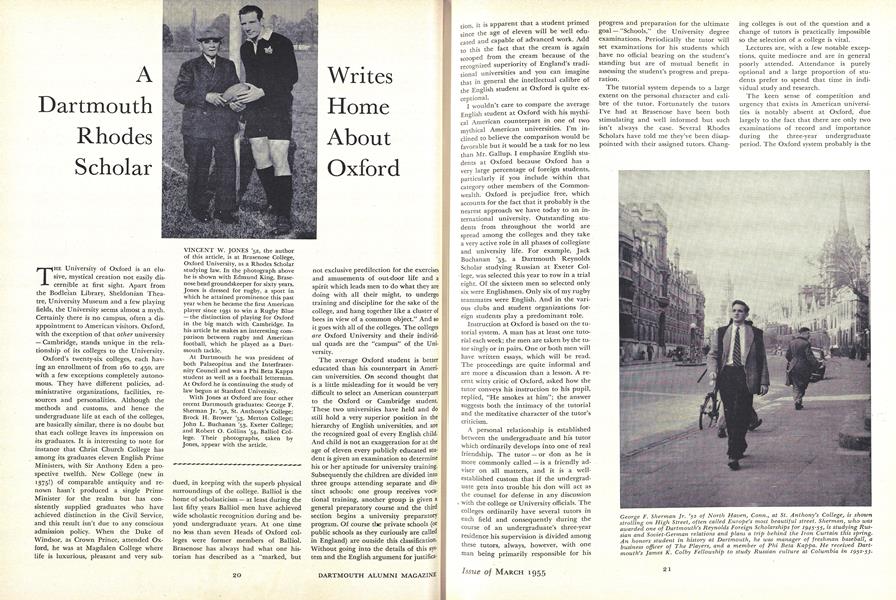

George F. Sherman Jr. '52 of North Haven, Conn., at St. Anthony's College, is shownstrollina on High Street, often called Europe's most beautiful street. Sherman, who wasawarded one of Dartmouth's Reynolds Foreign Scholarships for 1945-55, is studying Russian and Soviet-German relations and plans a trip behind the Iron Curtain this spring.An honors student in history at Dartmouth, he was manager of freshman baseball, abusiness officer of The Players, and a member of Phi Beta Kappa. He received Dartmouth's James K. Colby Fellowship to study Russian culture at Columbia in 1952-53.

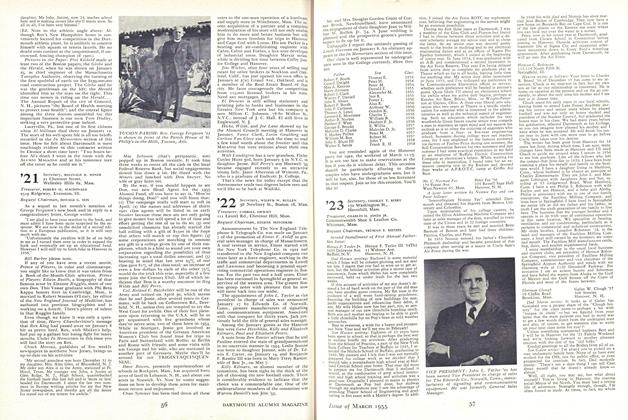

Robert O. Collins '54 (left) of Waukegan, Ill., at Balliol College, and Brock H. Brower '53of Westfield, N. J., at Merton College, are shown in the Quad at Christ Church Collegewith Sir Christopher Wren's Tom Tower - the Everest of Oxford - in the background. Brower, former editor-in-chief of The Dartmouth and chairman of Palaeopitus, is in his first year as a Rhodes Scholar and is studying English literature. He was at Harvard LawSchool for one year following graduation from Dartmouth as a Rufus Choate Scholar.Collins was one of the first group of American college students awarded Marshall Scholarships for two years of study in England - awards expressing Britain's gratitude for Marshall Plan aid. He is studying English history at Balliol and reading for an honors degree. A top history student at Dartmouth, he also was enrolled in the Northern Studiesprogram and was active in mountaineering, a helpful preliminary to scaling Tom Tower.

John L. Buchanan '53 of Wray, Colorado, who is studying Russian at ExeterCollege, is one of Oxford University's leading oarsmen. He received one ofDartmouth's Reynolds Scholarships to study at Oxford in 1953-54 and is continuing for a second year by means of a Ford Foundation grant. A Phi BetaKappa student and Outing Club leader, he majored in Russian Civilization atDartmouth. In addition to the Russian language, his Oxford studies includesocial and political aspects of the Soviet Union and Balkan states.

Climbing at Oxford includes late entry afterthe college gates are closed at midnight. BrockBrower '53, for photographic purposes only,makes a daytime reconnaissance at a spotwhich we're sure is given a wide berth.

LOUIS E. LEVERONE '04, national vicechairman of the Tucker Foundation FundCommittee.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureTHE BEGINNINGS of Dartmouth's Alumni Organization

March 1955 By ERNEST MARTIN HOPKINS 01 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

March 1955 By CHRISTIAN E. BORN, EDWIN C. CHINLUND -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

March 1955 By G. H. CASSELS-SMITH '55 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

March 1955 By CHESLEY T. BIXBY, CHARLES H. JONES JR., TRUMAN T. METZEL -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

March 1955 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, RICHARD P. WHITE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

March 1955 By HERBERT H. HARWOOD, H. DONALD NORSTRAND, RICHARD M. NICHOLS

Features

-

Feature

FeatureHANDYMAN'S SPECIAL

APRIL 1989 -

Feature

FeatureDinner at Dartmouth

July/Aug 2003 -

FEATURE

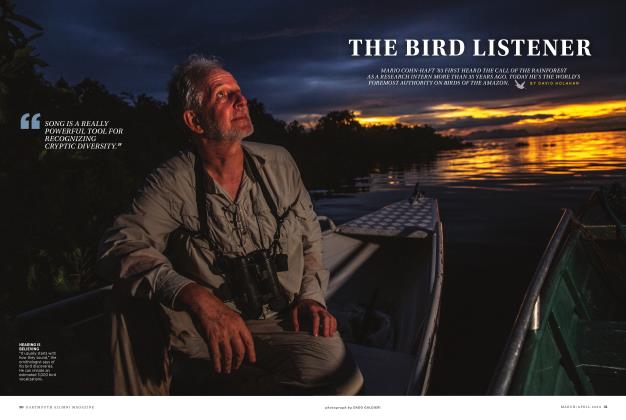

FEATUREThe Bird Listener

MARCH | APRIL 2024 By DAVID HOLAHAN -

Cover Story

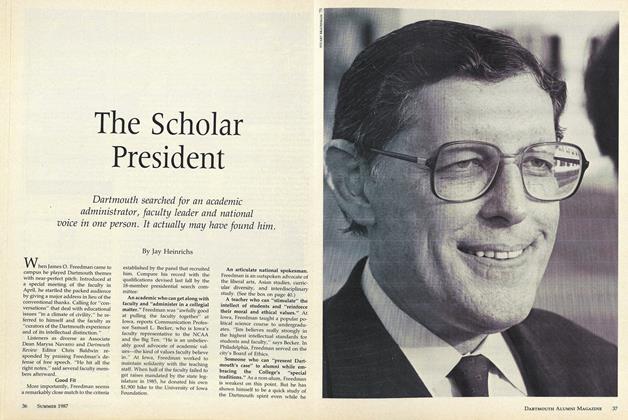

Cover StoryThe Scholar President

June 1987 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

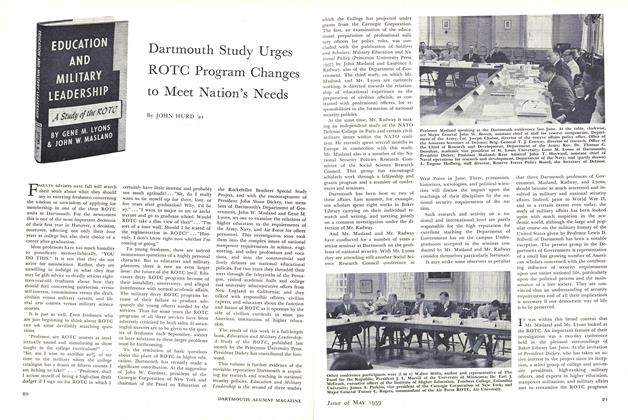

FeatureDartmouth Study Urges ROTC Program Changes to Meet Nation's Needs

MAY 1959 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Feature

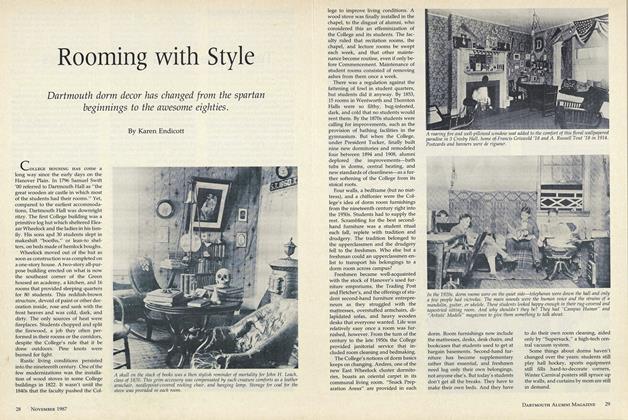

FeatureRooming with Style

NOVEMBER • 1987 By Karen Endicott