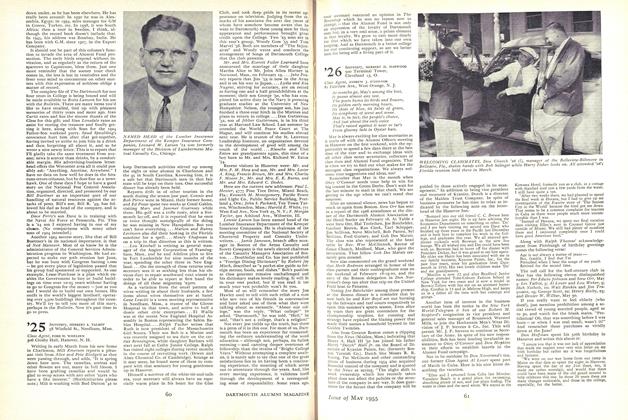

President Nathan Lord

THE Reverend Nathan Lord became President of Dartmouth College in 1828 while it was still struggling to recover from the exhausting effects of the College controversy. When he resigned thirty-five years later his able leadership had secured for the College conspicuous growth, a doubling of the enrollment, increased endowment, an enlarged curriculum, and a high standing among the colleges of the time. Significant as these achievements were it was not so much because of his success as an administrator that he was acclaimed New Hampshire's leading citizen but for his magnetic personality. His superior intellectual powers, his sterling character, his deep-rooted religious beliefs and, above all, his graciousness of spirit won the respect and affection of all who knew him. One man expressed the common feeling about him when he said, "It was more pleasant to disagree with Dr. Lord than to agree with most men."

Nathan Lord came of a Maine family and went to Bowdoin College, from which he was graduated in 1809, before he was seventeen years old. After teaching at Phillips Exeter Academy for three years, he went to Andover Theological Seminary, receiving his degree in 1815. The following year he was installed as the minister of the Congregational Church in Amherst, N.H., where he remained twelve years. His ministry revived interest in religion which had been at a low ebb and strengthened the church. He was especially friendly to children and young people over whose upbringing he was ever watchful. The impression he made on them during those twelve years was so lasting that it carried to their descendants two or three generations later who held a special celebration in the Amherst church in 1916 to commemorate the centennial of his installation as pastor. His pastorate would undoubtedly have continued longer had he not been afflicted by a throat ailment which periodically caused the loss of his voice. Doctors warned him that it would prevent him from carrying out the heavy preaching schedule required of a minister. When the presidency of Dartmouth College became vacant following the resignation of President Tyler, his fellow Trustees importuned him to accept it. He was the natural choice for the position because of his acknowledged ability and because his service as Trustee of the College since 1821 had made him familiar with its affairs. Reluctantly, he gave up his hopes for a ministerial career and acceded to their wish.

As would be expected of one brought up in the atmosphere of early nineteenth century New England, Nathan Lord was a firm believer in Calvinistic theology. This belief was enhanced by his study at Andover, orthodox Congregationalism, divine sovereignty and predestination, the depravity of man, and the grace of God as the only means of salvation. Dr. Lord accepted these doctrines and made them the guiding principles of his life, but his independence of mind was such that he gradually reshaped them to his own thinking.

When the Trustees of the College asked him to conduct the classes in ethics and theology, his sense of duty to give the students the best instruction he could impelled him to begin a thorough and conscientious re-examination of his beliefs. This carried him into a scholarly and searching study of the Bible and theology extending over many years, a period which he said "was the most instructive and rewarding of my life" and in the course of which "my conviction of the cardinal and vital truths of Scripture was greatly strengthened." He reached the conclusion that there was an irreconcilable inconsistency between the truths of the Bible and the commonly accepted opinions regarding Christianity, and the secular speculative philosophy of the time .was making the will of God subordinate to its own visionary pretensions. It was with much sorrow that he felt compelled to break away from the liberal trend of current thinking, but he could take no other course than to follow the dictates of his convictions, regardless of the opprobrium he knew would come to him.

The theological beliefs which he then espoused and which thereafter directed both his private and his public life can be stated in a few essential principles. God reigns in the world: His will is the law of His kingdom. Man is subject to it but he has rebelled and therefore suffered punishment, death and the many special penalties which afflict this world. God was revealed in Jesus Christ to whom he gave all authority and power over heaven and earth and in whom man should have implicit belief. His kingdom is unending: some day human kingdoms will be redeemed and partake of the visible glory of the church triumphant. This theology was not merely a set of dogmas to be proclaimed, a creed for mere intellectual assent; it was an intensely personal belief which motivated all his thinking and transformed his whole being. These were eternal truths to be lived by. From his unreserved allegiance to them he gained a boldness to champion the course in life that meant so much to him and an equanim- ity of spirit that kept him undaunted.

The point at which Dr. Lord parted company with most of his contemporaries was in his insistence that the Bible was the only authority which men could rightly accept for their guide in life. It was in- fallible and its explicit promises were to be interpreted literally. His deductions from specific statements led him to a reso- lute but highly unorthodox belief in the pre-millenial coming of the Savior to reign as personal king upon earth and in the Biblical sanction of slavery.

President Lord set forth his views on the supremacy of the Bible in a baccalaureate discourse delivered in 1858 on the subject "The Bible the Guide of Life." He explained how it uses symbols as vehicles of truth and discussed the problem of its interpretation, which is difficult and dangerous if approached too dogmatically. A characteristic sentence sums up his stand: "No literary adornments, or metaphysical subtleties, or critical ingenuity, or rhetorical skill, or logical finesse, can change the meaning of an iota of the Word of God, or prevent its natural effect."

These were the theories he expounded to his classes, hoping to lead them into the right road of Biblical study. Later in life he wrote that his consciousness that he might be in error and his anxiety lest he mislead the students unwittingly kept him from adopting a proselyting spirit. He had been regretfully aware that "my teaching, on this line, was without effect," but he appreciated the respectful attention of the students, their earnest questionings and intelligent discussion; and, he concluded, "I could not learn that I was doing them any injury by what seemed to engage them as 'pecularities.'

IN 1833 when the American Anti-Slavery Society was formed, Dr. Lord had joined it gladly and was elected a vicepresident. When his later studies and reflections convinced him that slavery was a moral problem to be judged by Biblical standards, he reconsidered his opposition to it and became a leading pro-slavery advocate. He could give no support to any cause that rejected the Bible. To win support for his position he published in 1854 a 32-page pamphlet, A Letter of Inquiryto Ministers of the Gospel of all Denominations on Slavery by a Northern Presbyter, in which he developed the Biblical basis for slavery and justified it on worldly grounds.

Dr. Lord was more insistent than most men of his time on a literal interpretation of the Bible and if he seems to give its symbols too narrow a meaning and to disregard passages that convey a larger humanitarian message, it was because of his dedication to the glorification of God. His logical mind, his zeal for salvation, and his power of expression made him a conspicuous spokesman of these views.

By the time the Civil War broke out the number who supported him had dwindled to a small group, but he persisted in expressing his opinions, and neither the increasing popular hostility to him nor the fear of consequences could silence him. He believed the administration in Washington could have prevented the war, and he opposed it as not being God's way of remedying the evil of slavery. Late in 1862 he contributed to a Boston paper a letter, "A True Picture of Abolition," which blamed abolition as the cause of the war. It was widely publicized in an unauthorized and distorted version, which precipitated a crisis in the attitude toward him. Views which had been looked upon as harmless idiosyncrasies became dangerous when the country was at war. People could no longer disassociate his personal views from the fact that he held an official position in an institution in which full loyalty to the government was expected. It made no difference that he carefully avoided bringing these views to the campus and that the students were unaffected by them.

In the spring of 1863 a conference of New Hampshire ministers passed resolutions expressing their regard for the able administration President Lord had given the College but calling upon its Trustees to inquire whether the interests of the College, in the existing circumstances, did not call for a change in the presidency. This resolution was presented to them at their July meeting. They were on the spot. They supported the President in his administration of the College, but a major- ity believed that relations with the public were so badly strained that the College would suffer if a change were not made. They could not bring themselves to remove the President, but they wanted to show that the College was on the right side; so they passed resolutions in which they pledged the support of Dartmouth College to the government and rejoiced in the hope that the evil of slavery would be doomed by the war.

No more effective and speedy way could have been found for obtaining the removal of President Lord than to bring into the open this implied censure of him. He had anticipated their action and was prepared for it. Leaving the meeting for a few minutes, he returned with a letter of resignation as President and Trustee. He stated that the charge against him was not for official delinquency but for his personal opinions, and he protested unequivocally the right of the Trustees to impose the conditions which the resolution implied. His loyalty to the country had been proved by seventy years of devotion to its principles even though he now disagreed with the present policy of the government.

"I take the liberty respectfully to protest against their (the Trustees) right to impose any religious, ethical, or political test upon any member of their own body or any member of the College Faculty, beyond what is recognized by the Charter of the Institution For my opinions and expressions of opinion on such subjects (Biblical ethics), I hold myself responsible only to God, and the constitutional tribunals of my country."

Since his opinions were considered to be injurious to the College, and since he did not want to be placed in strained relations with it, he found it inconsistent with Christian charity and propriety to carry on my administration." He closed the letter by expressing his gratitude to the Trustees for their many kindnesses to him in the past and wishing peace and prosperity to the College.

This seems like an abrupt and inglorious ending to a service of forty-two years in which President Lord had done so much for the College, but to a man of his convictions the implications of the Trustees' resolutions left no choice other than resignation. The prerogatives of official position or personal prestige were of minor importance to him. What he valued above all else and could not surrender was the right to speak out freely on issues of personal belief. His whole life had demonstrated the principle that the right of an individual to follow his own conscience was greater than the right of a majority to require conformity to its will. Intellectual freedom for himself and for the College community was a precious possession that was worth any sacrifice to maintain.

THE high esteem in which President Lord was held in New England during his long career as pastor and president was due to the forcefulness of his preaching and to the effective use of his intellectual powers. Those who had the intimate associations of daily and informal contact with him were more deeply moved, however, by the goodness and warmth of his personality. It was the contagion of his friendliness, of his feeling that life was good, which impressed his associates more than his solemnity. He had a rare combination of traits apt to be antagonistic, strength tempered with sweetness, a "martyr-like boldness and persistency with the utmost courtesy, gentleness, and kindness," pathos accompanied by humor. As one admirer said of him: "In Dr. Lord's character there are singularly linked with all his inflexibleness, his courage, his fearless individuality, his unrelenting warfare against error and wickedness, a courtesy, a gentleness of manner, a tender interest in the welfare of others, which won all hearts."

He possessed an integrity of character that was never shaken, a singleness of purpose that knew no fear, a serenity that remained unruffled by adversity, and withal a charm and graciousness of manner that was the natural outpouring of a kindhearted and joyous disposition. His respect for the nobility which he saw in all men gave him a love for people that drew forth their love in return. He believed that a true gentleman never failed in acts of courtesy, and even in the midst of bitter controversy he never gave way to unkindness or rudeness. Despite the circumstances of his resignation, no one ever heard him utter an unkind word against those who brought it about, nor did he permit others to do so. He was gifted with a ready sense of humor which bubbled up within him to relieve the tension of a trying moment or to lighten the austerity of his thought. It was these human and lovable characteristics that affected his contemporaries so vividly, rather than his views on theology and slavery.

In his conduct of College affairs President Lord had two principal objectives. He wanted to help the students to learn how to use their minds effectively and he wanted to make Dartmouth known as a Christian college where one would get a sound religious education. To make sure that they took advantage of their opportunities, a strict discipline was maintained. When the students became unruly he would hasten to quell the disturbance, and if the commanding effect of his voice demanding, "Desist, gentlemen," failed to secure order, he did not hesitate to use more persuasive measures by swinging the cane he customarily carried. Cases of individual discipline were handled in his study where the unlucky student might be given a severe grilling, but if he was penitent he would often find that the cloud of discipline had a silver lining. One graduate wrote that President Lord had a "remarkable faculty of administering reproof and discipline in so practical a way as to give no offense." He commonly wore a pair of green tinted glasses which in the students' opinion were not so much to protect his eyes as to permit them to rove over the scene without his penetrating glance becoming apparent — or perhaps to keep the student from catching the twinkle of humor that relieved the sternness of his countenance.

He was a great reader, and next to the Bible he was especially fond of the English poets. His memory was very retentive and he knew long passages by heart. One night some students, curious to see what would happen, took the Bible from the chapel pulpit. In the morning they watched President Lord intently as he came in, but saw no sign of his noticing anything unusual. When it came time for the Bible reading, he repeated the 119th psalm verbatim, and thereafter the Bible was left in its proper place.

He had an extraordinary gift for extemporaneous prayer. Some of his prayers were taken down in shorthand and preserved to show their sublimity of thought and beauty of expression. There was a majesty of language, a yearning to bring the blessing of God upon the students that could be deeply affecting. As one of them said, "I like to hear Dr. Lord pray, I like to hear him say: 'The Lord bless these young men, every one of them,' for then I feel safe for the day."

President Lord's reflections on the Negroes as a race were entirely theoretical and impersonal. Toward individual members he was compassionate and always solicitous for their welfare. Believing that the best way to help them was to give them the benefits of a good Christian education, he admitted many Negroes to Dartmouth, which was at the time perhaps the only college in the country to give them that privilege. He was sometimes a little embarrassed to express his racial views in their presence, but both he and they met the situation with dignity and mutual respect. When one of them later entered the ministry and was to be ordained in a church at Troy, N.Y., he invited Dr. Lord to give the ordination sermon. He was the only one of the white ministers invited to the ceremony who was willing to attend.

Following his resignation Dr. Lord continued to live in Hanover for the seven years that remained of his life. Letters he wrote at that time showed that he was as happy to be free from the cares of office as a schoolboy is on his last day of school. But retirement did not mean an end to his activity. He maintained his intellectual pursuits, kept up correspondence with his friends, and occupied pulpits in which he was invited to preach. His health was good, and he found great pleasure in such interests as working in his garden, going duck hunting with one of his sons on the coast of Maine, or skating on the river in winter.

The success of the College remained as close to his heart as ever, and he thought much about it. The centennial of its founding was observed in 1869 by special exercises in Commencement week at which he had been invited to give an address. Ill health prevented him from being present, but he sent a message of affection for the College and hope for its future. He recognized the importance of alumni interest to the College and helped pave the way toward that alumni participation in College affairs which has been so significant in Dartmouth's recent history.

With plenty of time in his retirement for reflection, he became still more convinced of the ultimate truth and justification of his ideas on religion and education. He wanted to urge them once more on his former students and therefore used the occasion of the centennial celebration to write "A Letter to the Alumni of Dartmouth College," which was published in a book of ninety pages. The theme of his letter was "The peculiar responsibility which Christianity now imposes upon educated men." He reminded the alumni that the College was founded to teach Christ to the Indians and to any others whom it should reach. The great aim of his administration had been to extend the influence of Christ, and he hoped that Dartmouth would always seek to fulfill that mission. He told them that the future of the country was mainly in the hands of its educated men and that this placed a grave responsibility upon them to learn and to follow the will of God if the nation was to be preserved. He closed with an injunction to the College of the next one hundred years, which Dartmouth men may still heed:

"Nor can I give up the expectation- that the venerable College itself, whose voice, a hundred years ago, cried so effectually in the desert, will, within the hundred years to come, cause itself to be heard, - uttering - the empathic cry of the true Elias, 'Prepare ye the way of theLord, make his paths straight.' "

President Nathan Lord

THE AUTHOR is the great-grandson of President Nathan Lord, about whom he writes in this article. A member of one of Dartmouth's most notable families, he is the grandson of the Rev. John King Lord, 1836; the son of the late "Johnny K" Lord, 1868, beloved member of the Dartmouth faculty who was Daniel Webster Professor of Latin for many years and Acting President of the College in 1892-93; and brother of John King Lord '95 and Dr. Frederic P. Lord '98. A multitude of uncles and cousins also attended Dartmouth. A native of Hanover, Arthur Lord taught in schools in Illinois, at Tabor Academy and at Lynn (Mass.) Classical High School where he was head of the mathematics department from 1919 to 1926. In the latter year he began his present association with the Boston publishing firm of Ginn and Company. Mr. Lord now resides in Newton, Mass.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Life of the Mind

May 1955 By DR. ALAN GREGG, -

Feature

FeatureFreedom and Discipline

May 1955 By AMOS N. BLANDIN JR. 18 -

Feature

FeatureThe Education of a Freshman

May 1955 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

May 1955 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

May 1955 By G. H. CASSELS-SMITH '55 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

May 1955 By HERBERT H. HARWOOD, ANDREW J. O'CONNOR

ARTHUR H. LORD '10

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLETTERS

March 1960 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLETTERS TO THE EDITOR

June 1962 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLETTERS TO THE EDIOR

JUNE 1964 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

SEPT. 1977 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

NOVEMBER 1984 -

Article

ArticleHanover: Something Unusual Happened

June 1975 By ARTHUR H. LORD '10

Features

-

Feature

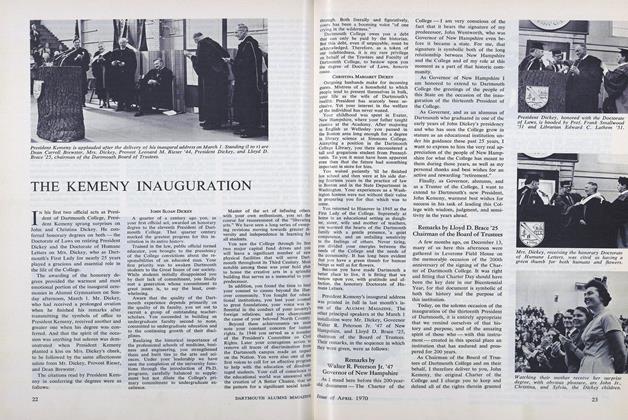

FeatureTHE KEMENY INAUGURATION

APRIL 1970 -

Feature

FeatureNine-Man Council Charts Course for Development

January 1954 By GEORGE H. COLTON '35 -

Feature

FeatureCollege Staff Members Reach Retirement

JULY 1972 By J.D. -

Feature

FeaturePeter Smith's Tribal Links

Novembr 1995 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Feature

FeatureBuilding a Better Student Body

OCTOBER • 1987 By Thurman Zick -

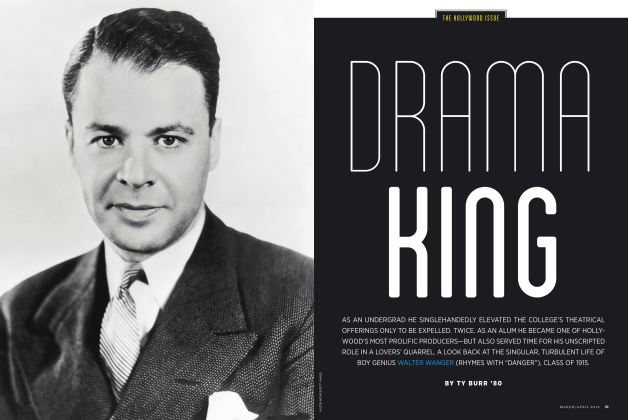

Feature

FeatureDrama King

MARCH | APRIL By TY BURR ’80