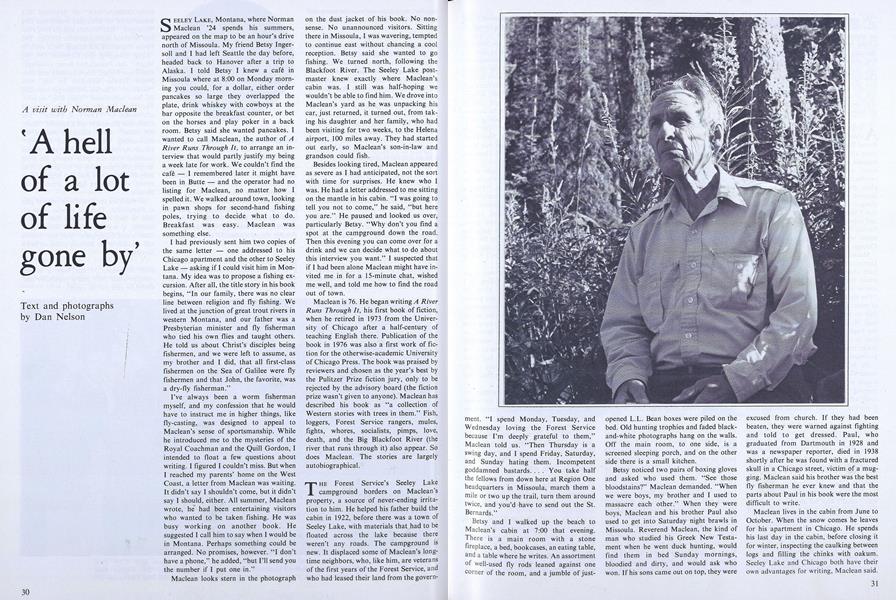

A visit with Norman Maclean

SEELEY LAKE, Montana, where Norman Maclean '24 spends his summers, appeared on the map to be an hour's drive north of Missoula. My friend Betsy Ingersoll and I had left Seattle the day before, headed back to Hanover after a trip to Alaska. I told Betsy I knew a café in Missoula where at 8:00 on Monday morning you could, for a dollar, either order pancakes so large they overlapped the plate, drink whiskey with cowboys at the bar opposite the breakfast counter, or bet on the horses and play poker in a back room. Betsy said she wanted pancakes. I wanted to call Maclean, the author of ARiver Runs Through It, to arrange an interview that would partly justify my being a week late for work. We couldn't find the cafe - I remembered later it might have been in Butte - and the operator had no listing for Maclean, no matter how I spelled it. We walked around town, looking in pawn shops for second-hand fishing poles, trying to decide what to do. Breakfast was easy. Maclean was something else.

I had previously sent him two copies of the same letter - one addressed to his Chicago apartment and the other to Seeley Lake - asking if I could visit him in Montana. My idea was to propose a fishing excursion. After all, the title story in his book begins, "In our family, there was no clear line between religion and fly fishing. We lived at the junction of great trout rivers in western Montana, and our father was a Presbyterian minister and fly fisherman who tied his own flies and taught others. He told us about Christ's disciples being fishermen, and we were left to assume, as my brother and I did, that all first-class fishermen on the Sea of Galilee were fly fishermen and that John, the favorite, was a dry-fly fisherman."

I've always been a worm fisherman myself, and my confession that he would have to instruct me in higher things, like fly-casting, was designed to appeal to Maclean's sense of sportsmanship. While he introduced me to the mysteries of the Royal Coachman and the Quill Gordon, I intended to float a few questions about writing. I figured I couldn't miss. But when I reached my parents' home on the West Coast, a letter from Maclean was waiting. It didn't say I shouldn't come, but it didn't say I should, either. All summer, Maclean wrote, he had been entertaining visitors who wanted to be taken fishing. He was busy working on another book. He suggested I call him to say when I would be in Montana. Perhaps something could be arranged. No promises, however. "I don't have a phone," he added, "but I'll send you the number if I put one in."

Maclean looks stern in the photograph on the dust jacket of his book. No nonsense. No unannounced visitors. Sitting there in Missoula, I was wavering, tempted to continue east without chancing a cool reception. Betsy said she wanted to go fishing. We turned north, following the Blackfoot River. The Seeley Lake post-master knew exactly where Maclean's cabin was. I still was half-hoping we wouldn't be able to find him. We drove into Maclean's yard as he was unpacking his car, just returned, it turned out, from taking his daughter and her family, who had been visiting for two weeks, to the Helena airport, 100 miles away. They had started out early, so Maclean's son-in-law and grandson could fish.

Besides looking tired, Maclean appeared as severe as I had anticipated, not the sort with time for surprises. He knew who I was. He had a letter addressed to me sitting on the mantle in his cabin. "I was going to tell you not to come," he said, "but here you are." He paused and looked us over, particularly Betsy. "Why don't you find a spot at the campground down the road. Then this evening you can come over for a drink and we can decide what to do about this interview you want." I suspected that if I had been alone Maclean might have invited me in for a 15-minute chat, wished me well, and told me how to find the road out of town.

Maclean is 76. He began writing A RiverRuns Through It, his first book of fiction, when he retired in 1973 from the University of Chicago after a half-century of teaching English there. Publication of the book in 1976 was also a first work of fiction for the otherwise-academic University of Chicago Press. The book was praised by reviewers and chosen as the year's best by the Pulitzer Prize fiction jury, only to be rejected by the advisory board (the fiction prize wasn't given to anyone). Maclean has described his book as "a collection of Western stories with trees in them." Fish, loggers, Forest Service rangers, mules, fights, whores, socialists, pimps, love, death, and the Big Blackfoot River (the river that runs through it) also appear. So does Maclean. The stories are largely autobiographical.

THE Forest Service's Seeley Lake campground borders on Maclean's property, a source of never-ending irritation to him. He helped his father build the cabin in 1922, before there was a town of Seeley Lake, with materials that had to be floated across the lake because there weren't any roads. The campground is new. It displaced some of Maclean's long-time neighbors, who, like him, are veterans of the first years of the Forest Service, and who had leased their land from the government. "I spend Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday loving the Forest Service because I'm deeply grateful to them," Maclean told us. "Then Thursday is a swing day, and I spend Friday, Saturday, and Sunday hating them. Incompetent goddamned bastards. ... You take half the fellows from down here at Region One headquarters in Missoula, march them a mile or two up the trail, turn them around twice, and you'd have to send out the St. Bernards."

Betsy and I walked up the beach to Maclean's cabin at 7:00 that evening. There is a main room with a stone fireplace, a bed, bookcases, an eating table, and a table where he writes. An assortment of well-used fly rods leaned against one corner of the room, and a jumble of justopened L.L. Bean boxes were piled on the bed. Old hunting trophies and faded black- and-white photographs hang on the walls. Off the main room, to one side, is a screened sleeping porch, and on the other side there is a small kitchen.

Betsy noticed two pairs of boxing gloves and asked who used them. "See those bloodstains?" Maclean demanded. "When we were boys, my brother and I used to massacre each other." When they were boys, Maclean and his brother Paul also used to get into Saturday night brawls in Missoula. Reverend Maclean, the kind of man who studied his Greek New Testament when he went duck hunting, would find them in bed Sunday mornings, bloodied and dirty, and would ask who won. If his sons came out on top, they were excused from church. If they had been beaten, they were warned against fighting and told to get dressed. Paul, who graduated from Dartmouth in 1928 and was a newspaper reporter, died in 1938 shortly after he was found with a fractured skull in a Chicago street, victim of a mugging. Maclean said his brother was the best fly fisherman he ever knew and that the parts about Paul in his book were the most difficult to write.

Maclean lives in the cabin from June to October. When the snow comes he leaves for his apartment in Chicago. He spends his last day in the cabin, before closing it for winter, inspecting the caulking between logs and filling the chinks with oakum. Seeley Lake and Chicago both have their own advantages for writing, Maclean said. "My apartment is much faster to operate than the cabin. When you're single, it takes an enormous amount of time just to live. Living in the cabin is complicated. Each morning I have to bring in the wood, light a fire, and sweep before I can get to work. I can start writing an hour sooner in Chicago. When I'm conceiving and writing first drafts, though, I like to be here. I can talk to my old Forest Service friends. I often go to the headquarters in Missoula to do research."

AFTER helping his father build the cabin, Maclean went to work for the Forest Service, a career he intended to continue after college. "I went to Dartmouth because at that time it was the only outdoor college in the country," he recollected. "Dartmouth was a strange place for a Montana boy to be, but I showed those bastards how to use a shotgun and a fishing pole. After graduation I taught at Dartmouth for two years and hated it. So I went back to the Forest Service for two years and hated that, too. I ended up teaching at the University of Chicago for 50 years."

Maclean was given his start teaching at Dartmouth when Professor David Lambuth, chairman of the English Department, asked him if he wanted to help with a course and with correcting some papers. "The class was full of some poker buddies of mine, and I figured it would be a good way to pay back some debts," Maclean said. He complained that as a member of the English Department he had to wear a coat to dinner, and implied that he had a better time as a student than he did as a professor.

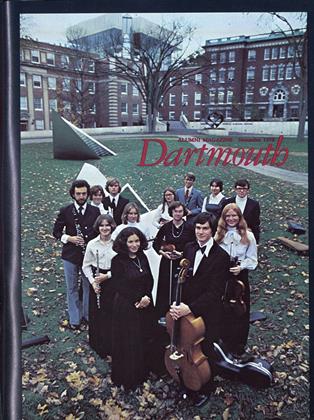

He told us about a Winter Carnival vaudeville act he and a friend produced and staged at various fraternities "in hopes of meeting some girls since neither one of us could afford to bring up dates of our own. It worked." The act consisted primarily of an intoxicated cat that was primed with sardines soaked in alcohol filched from the Biology Department. As undergraduates, Maclean and his friend Ted Geisel '25 (better known now as Dr. Seuss) edited the Jack O'Lantern. Geisel, Maclean remembered, had a habit of drawing in hymnals during chapel.

The summer after Maclean's second year of teaching at Dartmouth, his father, who "usually kept his mouth shut," called him aside and said, " 'You know, Norman, I don't think you've grown much this past year.' That really set me back," Maclean recalled. "I wrote Lambuth a letter and went back to the woods for a couple of years." He hasn't returned to Hanover since. After two years in the woods with the Forest Service, he went to the University of Chicago for graduate study and stayed on as a professor. While he was there he won the Quantrell Award for excellence in undergraduate teaching three times. No one else has won it more than once.

"I would have loved to have been a smokejumper," he confided. Asked what the requirements were, he laughed. "You have to be strong in the back, weak in the mind. You have to spend three years in the Forest Service, one year fighting fires. You have to be a little bit nuts. The smokejumpers are full of Ph.D.'s and lawyer-types who knew they were going to spend the rest of their lives sitting on their asses. They wanted to show themselves and the world what they were made of. They're the shock troops of the forest-fire fighters."

He thought for a moment and added, "There's no sense in regretting your past. What the hell are you going to do about it? If I wanted to regret it, I think I could. But I've had the privilege of teaching at a university that was very much like me, or at least could tolerate me. It has been a great place, full of big men who didn't mince words and wouldn't betray you. I've always made a point of being insolent; at Dartmouth I couldn't."

Maclean said he had no formula for successful teaching. "During my first year at Chicago I asked one of the senior professors to evaluate my teaching. He came to my class, observed, and said I did fine. I asked if that was all he could tell me. Weren't there any suggestions he could give me? He said to change my suit every day - or at least to change my necktie. That's all I've ever learned about teaching. Either you can or you can't. I've seen it done every way - standing on your head or sitting behind a desk." He remarked that he tried every year to teach half undergraduates, half graduate students. "But as I grew older," he added, "I tried to avoid teaching freshmen and sophomores." He taught mostly poetry and literary criticism, "and Shakespeare once a year, just to keep my literary values straight."

AT 9:00, as Betsy and I had promised him, we said good night and walked back to the campground. After spending the next morning writing, Maclean was to pick us up and take us on an afternoon hike. "I'm fished out for a while," he confessed. "Instead of going fishing, I'll take you up to the edge of the glaciers that made this country. Then we'll come back here for dinner and finish talking."

While Maclean was writing, we went canoeing. If we had wanted to fish the lake, he told us, we might have caught trout, bass, or salmon. He told us about going fishing with the local game warden, "who tied onto a seven- or eight-pound bass. He brought it in, unhooked it, released it and said, 'Stay there until you're big enough to fight.' I figured I'd better stick to trout."

Maclean picked us up in his Volvo at 2:00, right on time, and drove us north on highway 209, up the valley between the Swan range to the east and the Mission range to the west, where we were headed. He turned off on a dirt Forest Service road, made several turns onto other, steeper, more deeply rutted roads, and told us about how the glaciers carved the canyons and about how his favorite fishing river, the Big Blackfoot, was cut. The road followed a stream to the trail-head. "Maybe we'll go fishing on our way home after all," he said as we stopped. There was a rod on the back seat of the car.

"I like to hike up here to a lake at the base of the glaciers and watch the backpackers," Maclean told us. "You see great big long-legged women carrying as much weight as the men." He finished lacing his hiking boots, picked up his binoculars for spotting mountain goats, found a pail in the trunk for gathering huckleberries, and led the way up the trail. His pace was fast enough so that if I stopped to pick a berry or two I had to hurry to catch up.

Maclean talked most of the way to the lake, not about books and writing, as I vainly encouraged him to, but about the wildflowers we saw, his wildflower garden at the cabin, hunting trips, prospecting, fighting forest fires, winter in the mountains, and about the people who have tried to make their living there. When we reached the lake we watched the waterfalls starting from the snow on the peaks above us, looked for mountain goats but didn't see any, and learned what sort of fly Maclean would tie to catch the trout that were rising in front of us.

Back at the road Maclean loosened his boots, uncorked a thermos of ice water, and shared a mason jar full of bourbon, explaining that in Montana "an open bottle of booze can get you in trouble with the cops." We sat in the shade beside the stream and talked, fishing forgotten. He said he spent two or three years writing ARiver Runs Through It. "My wife had something to do with how it started. She was dead, and I wanted to do something beautiful to take her place. I didn't want to be a senior citizen. I wanted to stay young, so I turned back to youth. It was a defiance of old age."

I asked how much of the book was autobiographical and how much of it was yarn. "It's hard for me to answer whether my work is fiction or not," he replied. "Someone else who was there might not have seen what I saw. On the other hand, I think what I said was true. No one has ever challenged a factual statement in the book."

"What I remember are the moments when I saw my life taking on shapes and patterns," he continued. "Life takes on designs that aren't visible until they're pointed out by a storyteller. The designs are part of something bigger, although I'd hesitate to say what. A lot of people find my writing quite religious. Other people don't."

THE sun was setting by the time we returned to Maclean's cabin for dinner. He had concocted a beef stew that morning and it had been cooking all day. After eating, we sat on the porch listening to the loons and watching the stars come out. It was a warm night. Maclean described his working schedule: He gets up early every morning - about 6:00 - to write. "When I wake up," he explained, "I don't argue with it. There is no question of am I or am I not going to write. I just do it. But in the afternoon I try to get totally away from writing. I go for a walk every day, or go fishing, or garden, or visit friends. Then there is what I call the bathtub part of writing. I sit there until the water gets cold and try to concentrate on what I'm going to do the next day, and from what point of view. It's non-verbal. I just try to feel it."

The book Maclean is writing now is about a tragic 1949 Montana forest fire that raged through a place called the Gates of the Mountains, just after the smokejumper outfit was organized. Half the area was plains, the rest was heavy timber. The fire moved slowly at first, Maclean explained, but jumped into the high, dry grass, taking with it the "intensity of a timber fire and picking up the speed of a grass fire." The blaze raced up a canyon the smokejumpers were hiking down. The crew tried to retreat but the boss saw they couldn't make it. He dug in but the rest ran. Thirteen men died. Only two of the crew, beside the boss, survived.

"I find writing so goddamned hard," Maclean confided. "When I began, I used to go around with a notebook saving what I thought were precious, jeweled sentences. I found out that wasn't worth a crap. By the time you bring your story around to using those sentences, the fox has gone the other way. I expect to be constantly right emotionally, but I don't expect the words to be right the first time. My work is constantly revised. It's easy to fall in love with your own corruption." When he is finally finished, he said, he is usually satisfied. There are one or two sentences in A RiverRuns Through It that he might change if he could.

Maclean claimed he had no advice to offer a young writer. "I didn't start writing until I was 70. For me it was impossible to be an academic and do non-academic writing. The 'l' who tells these stories has seen a hell of a lot of life go by. He venerates youth, but he looks back without sentimentality, although with great regret. When I was young, I found the world very tolerant of my eccentricity. Then the world closes in on you. There only are so many slots open for each generation. Then the slots fill up and the world doesn't give a damn. Who the hell are you? Someone else comes along.

"When I was 65 I went into my bedroom and said to myself, 'You're 65. Don't take any crap from anyone.' This business about identity being a crisis only for the young is a bunch of nonsense. If you're worth your salt, it's a problem all your life. I'm more concerned now about who I am than I ever was."

Dan Nelson '75 wrote "Five Days to BigRapids," about the St. John River, in theSeptember issue. He is an assistant editorof the ALUMNI MAGAZINE.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Researcher and the Teacher

November 1978 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureJazz Comes to College

November 1978 By Dick Holbrook -

Feature

FeatureMaking Music

November 1978 By Dana Grossman -

Article

ArticleThe Joy of Moving

November 1978 By W.B.C. -

Article

ArticleMan of the Cloth

November 1978 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleWhy the NCAA

November 1978 By SEAVER PETERS '54

Dan Nelson

-

Feature

FeatureA Delicate Balance

November 1975 By DAN NELSON -

Feature

FeatureES 21

January 1977 By DAN NELSON -

Feature

FeatureSee How They Run

NOV. 1977 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureShhh. There still are idealists abroad and they're called the Peace Corps

JUNE 1978 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureThe Trustees: 15 men and a woman with ultimate authority

October 1979 By Dan Nelson -

Cover Story

Cover StoryIn Two Worlds

May 1980 By Dan Nelson

Features

-

Feature

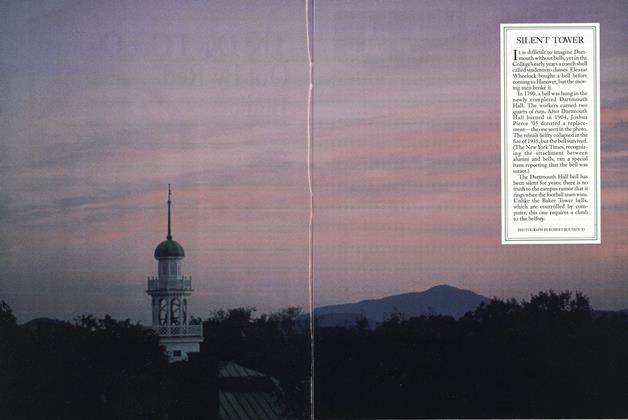

FeatureSILENT TOWER

NOVEMBER 1989 -

Feature

FeatureTHE BEGINNINGS of Dartmouth's Alumni Organization

March 1955 By ERNEST MARTIN HOPKINS 01 -

Feature

FeatureA Course About Themselves

January 1954 By FRANK PEMBERTON -

Cover Story

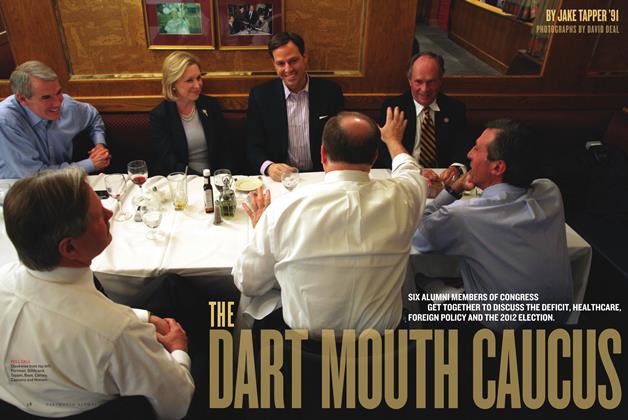

Cover StoryThe Dartmouth Caucus

July/August 2011 By Jake Tapper ’91 -

Feature

FeatureThe Old Guard

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Mike McGean '49 -

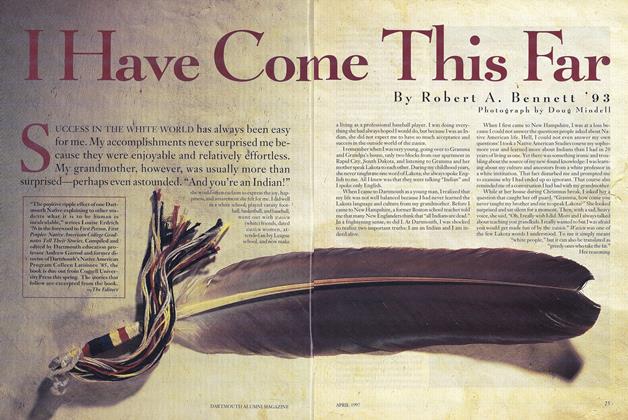

Cover Story

Cover StoryI Have Come This Far

APRIL 1997 By Robert A. Bennett '93