THE COMMENCEMENT ADDRESS

UNITED STATES SENATOR FROM NEW YORK

I WANT to say first that it's a pleasure and honor to be here. I shall always treasure this honorary degree. Secondly, let me say to the graduating class that, as they say in the theatrical business, James Witten Newton is quite an act to follow. But I will try.

Interestingly enough, because it indicates the nature of our times, my speech very logically follows his, but I have a different way for you to save yourselves. My way is to save your soul and to save our nation. I am not a preacher concerned with the laying on with a nice easy hand and getting everybody together in unity; I am an activist, as President Dickey's citation so very gratifyingly says, and I'll give you a program of action — a program of action that will not only save our skins but save our country, and save our souls, which urgently need it. I think it is important to realize that the gravest problem in our country today is this very divisiveness which we heard.

This is one of the most disturbing periods of our lives and in the life of our nation. Interestingly enough, in my own prepared text the very same word appears that appeared in Mr. Newton's text. The word is cancerous, and I wrote, "What is the reason for this cancerous growth in a time of overall prosperity when all should be order and quiet and contentment?" Some — indeed many, looking at the white armbands today — say the reason is the war in Vietnam; others not wearing armbands also identify the war in Vietnam as the source of unrest. Others say that it is the failure to eradicate poverty. Still others point to the apparent inability of the nation to assure a full measure of justice to all citizens.

I am going to have something to say — because I am one of those in power — about the statement made in the valedictory that you are being manipulated for a national effort. Remember there are 200 million of us - not just you and me and some others.

Now is an interesting time, but, we have been involved in unpopular wars before. And we have also been involved in popular wars. Has anybody thought of that? What about this same speech you just heard at the time when Hitler's legions marched with iron boots over most of Europe?

We have also had poverty and slums and ghettos for a long time; I ought to know, as President Dickey told you. Many of us, at least, have long been conscience-stricken by inequality and injustice among many of our own people, especially Negroes, 10 per cent of the American population.

But fundamentally the root of our present difficulty lies in our own expectations. We instinctively believe that after the holocaust of World War II we should be on the threshold of a golden age — certainly in the United States; that after achieving much of the affluence we worked so hard to attain, we should now be able to correct the truly unacceptable social, economic and political conditions which we face. The root cause, in short, is irritation and impatience with the seeming inability of the constitutional process to produce peace, to accommodate change, to correct injustices without explosive confrontations.

This feeling of impatience with the inability of our institutions to accept and guide change is even more pronounced on the college campuses of our country than it is in the nation at large. For, it is on the campus that the politics of confrontation has been framed and the politics of intimidation has been practiced.

Now politics of intimidation has within it the seeds of its own defeat, particularly when it is adopted by alienated elements of the society. For, if the self-appointed guardians of the status quo come to see that intimidation and violence are reaping rewards when practiced by the weak and disinherited, you know they might just emulate those techniques—turning force against its present practitioners.

But, a good many of the students at Dartmouth and at other universities have found another way to vent their outrage at the ills and injustices of our society. That is the doctrine being so eloquently pleaded for by the Poor People's March in Washington now led by Dr. Abernathy, formerly led by Dr. Martin Luther King — the doctrine of non-violence.

Non-violence is not passive; it's extremely militant, I assure you, and can be superbly effective and that's the message of my speech today. We have seen what it can do. Think of those brave young people who sat on stools in cities and towns in North Carolina and who were beaten about the head because they dared to seek to be served in a white establishment. Think of the fact that it is they, not the dormitory sitters and the burners of papers, who brought about the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. We have seen dedicated young men and women, concerned with the need to bring peace to the world, proclaiming their opposition on moral grounds to the Vietnam War; we have also seen an attitude among the young in Senator McCarthy's campaign which said we're not trying to save our own skins, we're going to give our all to extricate you, the United States, from this war. We have seen still others who are vitally concerned with the political future of the nation laboring those long hours in the presidential primaries from New Hampshire to California, although regrettably many of them, under present law, are held to young to vote.

I can well understand why a good many students quite properly resent the idea of spending four cloistered years in college in the capacity of sponges while the world is ringing with highly controversial events in highly charged times — of absorbing knowledge about the world they live in while abstaining from any genuine participation in it.

There is no doubt in my mind that student protest was the critical catalytic fact in changing the direction of Vietnam policy. But the main point is that its effectiveness stemmed in direct proportion from persuasion by argument and not violence. The lesson to be drawn is not that violent civil disobedience — or mini-insurrection if you will — succeeds but rather that fathers and even Senators will sit up and take note when their sons hold passionate beliefs about the morality of public policy and propagate those beliefs.

It was the students who first perceived acutely the fallacies, the contradictions, and the reality gap between fact and profession, of the ever-deepening American intervention in Vietnam. Many of the older generation were at first too ready to concede the benefit of the doubt to an Administration which wanted us to believe that Vietnam really fit into the Cold War mold of communist aggression against democracy.

Yet it is an incontrovertible fact that involvement may lead to protest and protest, in some cases, may lead to violence. As was quoted here from President Dickey, after all the unread petitions, all the postponed decisions, and all the endless talk, violence, in the eyes of a dedicated minority, may seem the best way to get results far more promptly and effectively than the more orderly process by which grievances are normally redressed within this society. Moreover, violence at times appears to them to be worth the risks, particularly when it goes unpunished.

It is also a fact that our times have been nurtured on violence; that they inspire the fanatical; that the political discourse has lost much of the civility common to a quieter age; that moderation no longer gets you in the newspapers and that, all too often, there is precious little moderation even among those who gather the news.

It is this sort of climate that sets the stage for the psychopath to try his hand at winning Instant Immortality as I, and so many millions of Americans, have just had the tragic example in the unbelievably tragic assassination of my colleague in the Senate.

So to those who raise the cry that "violent protest works" I say that violence feeds violence. While civil disobedience may seem in the short run to produce forward movement, a second harsher phase is likely to follow in its wake. History teaches that this second phase generally brings a right-wing reaction and a bloody counter-reaction that will erase any temporary progress. The final result may well be massive intervention and a "police state" atmosphere as the government moves in to keep the warring factions apart.

In light of this clear and present danger, we must deprive the apostles of violence of the pragmatic argument that only violence works. We can do this by showing people, young and old, that something else also yields results and with far less cost. And that something else is political action — political action, and other forms of legal action as a means of persuasion.

This is why I believe we must clearly display to those who are attracted to violence that the laws of our land, including the Constitution, are capable — I emphasize the word capable — are capable of reform by non-violent processes. And this is why we must clearly show that politicians too, like myself, are apostles of change, not apologists or clever negotiators only for the status quo.

Now let me tell you from the depths of my own experience that there are no limits to the changes we can make. I mentioned before and I say again that I have long thought that the voting age should be set nationally at 18 in every state of the Union. It will take a Constitutional amendment — it can be done.

Now I'll give you another very radical suggestion. Some people are highly dissatisfied by the inaction which often results when a struggle develops between the Executive and Legislative branches of our government. I will mention one possible reform which, incidentally, was the subject of a debate when I was at New York University and a member of the debating team — and that was a long time ago, almost 30 years. One possible reform would be to convert the Federal system to a parliamentary system with governments being turned out of office through a simple vote of "no confidence" by a unicameral legislature. Now I am not subscribing to this idea, but I want to point out that the whole political system can be changed — quite legally again by a Constitutional amendment.

My colleague in the Senate, Majority Leader Mike Mansfield, just the other day proposed broad changes in the manner of electing a President. He would eliminate the electoral college and the national conventions entirely. He would introduce popular election of the President and a national primary election within each party. That is pretty radical stuff, isn't it? But that too can be effected under our system.

Now admittedly, amending the Constitution is slow and cumbersome. Yet it has been done 25 times and is done all the time — we just had one amendment on the poll tax. And even the amending process can be amended. The Constitution, as I have said, has been altered 25 times, but there have been many other changes of very major and deep character, and I refer to changes by law simply by action of Congress. Let me give you a few instances. I mention the Civil Rights Acts of 1964 and the Civil Rights Acts of 1965 which dealt with employment; public accommodations, including even retail stores; voting, and many other aspects of the injustices and inequality that have been practiced for a century upon some 22 million Negro citizens in the United States. We have the Medicare Act — a virtual revolution which is the precursor, in my judgment, for a much broader application of a mutual system of health protection for the American people — that was signed into law after five years of struggle and participated in, incidentally, by President John F. Kennedy when he was a member of the Senate. Federal aid to elementary and secondary education, the subject of the hottest kind of fight in this country, became law and is now being administered and gets some 200 billion dollars a year and will get more. And who will forget the struggles over social security and unemployment compensation? And one of my private struggles in what is often a parochial atmosphere in the Congress — the National Foundation on the Arts and Humanities, which took 16 years to effect but was effected and is now law.

On balance, those who seek to produce needed changes in our society are far better off when they utilize the system — a process that is capable of great flexibility — than they are in resorting to violence against the system with all its dangers of anarchy and counter-repression. Now here is what I suggest and they're in both the public and private domain. I have already spoken of the vigor of our young people and of giving 18-year-olds the vote. I have already identified myself with the doctrine of change — the openness to change — the willingness to change — the daring to change — and if there's anything which is the new politics, this, in my judgment, is it. But remember if you want a change it's not just you — the graduating class of Dartmouth that you have got to convince. I have 18 million New Yorkers to convince and you have 200 million Americans. And I say, go to it, more power to you, but you cannot do it alone.

Boards of trustees of some private colleges, we have now found, tend not to allow for students and faculty to voice their ideas and their own participation. A movement is now on foot, and a very good move, to insure the means for legitimate student and faculty influence, established in such a way to afford these members of the college community a meaningful voice in the higher educational affairs which so vitally concern them. They should be involved — not because it will avoid student demonstrations — but because it makes good sense.

We can move America forward toward fulfillment and avoid violence which only retards change and encourages divisiveness, if we view the contending forces in our land not as a reason for bloody revolution, but as a chance to begin a creative debate through which, by constitutional action, a more just society will emerge.

I have a third suggestion. I feel that our institutions of higher learning must become more relevant to and involved with needs of American life. You should not have, as Mr. Newton said, four cloistered years at Dartmouth. You ought to get out in the world, in the same way that those who attended land-grant colleges in another day served as agents of technical and social change in the earlier decades of this century and in the preceding century. So if the large urban universities and community colleges may have a role to play beyond liberal arts education they should be organized so they are capable of improving the life of the city near which they are located. They can serve a critical role in education, in job training and health and in many other activities. There are no longer any barriers of distance or of time; you don't have to take a horse and buggy to Boston. Our colleges should offer to their students education that is directly related to the quality of urban life and to the challenges and opportunities of our time.

I close as I began. We are not an old nation. We are a very young nation. We are a very vigorous nation. We are a very pioneering nation. Opportunity is still unlimited in this country, but opportunity in this country is not based on one's individual will or desire. That's not the way we operate. What we are going to learn out of this terrible disaster in Vietnam is that you can't operate alone in the world either, no matter how big or how rich or how powerful you are; that the dollar cannot be the world's monetary unit; that that unit of world trade is going to have to be created by the International Monetary Fund; that we can't interfere in every Latin American country if we don't like what's going on there. We're going to have to be guided by the vote of the OAS. You believe in that — all you radicals believe in that — well, believe in it for yourselves too. There's a great country to convince — it can be done, it has been done, and the challenge to you is to join in and do it.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature"People as Well as Things"

July 1968 By HARVEY P. HOOD '18 -

Feature

FeatureThe Senior Valedictory

July 1968 By JAMES WITTEN NEWTON '68 -

Feature

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

July 1968 -

Feature

FeatureReunion Week: Fun Plus Education

July 1968 -

Feature

FeatureCouncil Honors Three Alumni

July 1968 -

Feature

FeatureCOMMENCEMENT 1968

July 1968

Features

-

Feature

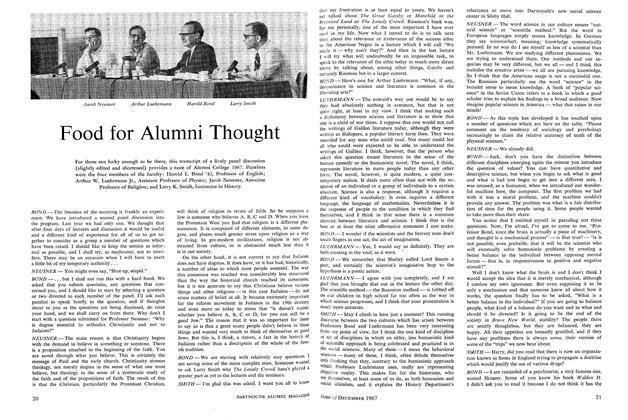

FeatureFood for Alumni Thought

DECEMBER 1967 -

Cover Story

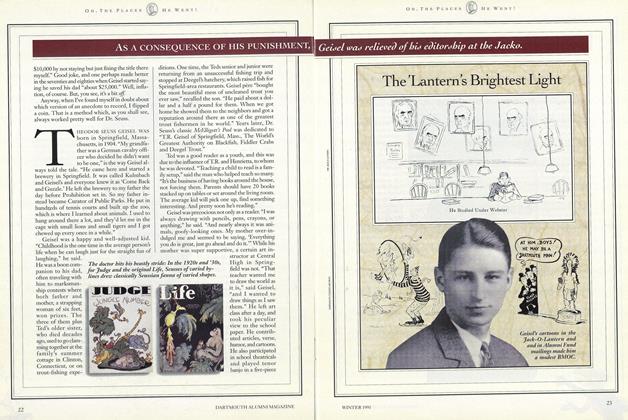

Cover StoryThe 'Lanterns' Brightest Light

December 1991 -

Cover Story

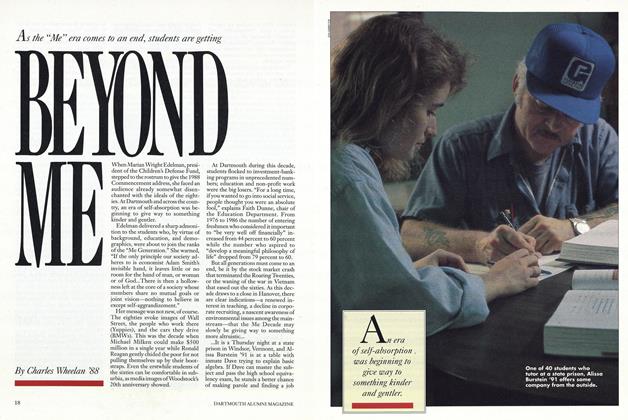

Cover StoryBEYOND ME

December 1989 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Feature

FeatureOldest Living Graduate, Will Be 100 This Month

APRIL 1964 By Dr. Edwin H. Allen '85 -

Feature

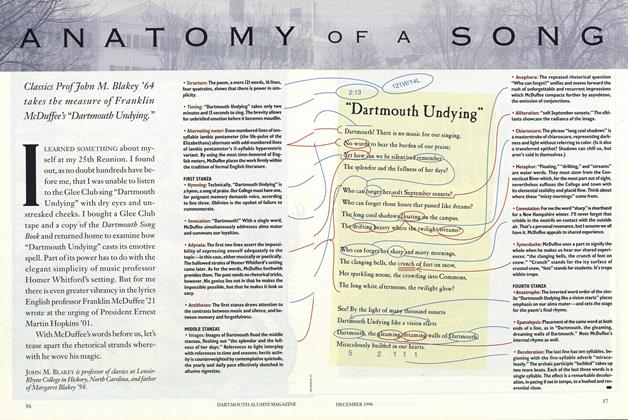

FeatureANATOMY OF A SONG

DECEMBER 1996 By John M. Blakey '64 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryCANCER

APRIL 1983 By Shelby Grantham