"Remember the ladies..."

IN February of my freshman year, I joined a group of Smith undergraduates who were traveling to a United World Federalist Conference at Princeton University. I believed in UWF, and had made speeches for it in high school, but I admit that the idea of meeting Princeton men was as exciting as world government.

All the Smithies were to be put up at the houses of professors. We dallied, driving through Manhattan, gawking at the skyscrapers. Dallying takes time, and we arrived at 2:00 a.m., four hours late. A furious person greeted us — a dreadful person who swore at us! All those elderly professors sitting up, waiting. "God damnit!" was my introduction to John Kemeny — three little words from my husband-to- be.

John Kemeny, a fresh Ph.D. in mathematics, was the faculty adviser to the Princeton student chapter of UWF. John Kemeny, who the previous summer had Spoken all over New Jersey to every possible group asking them to call for a strengthening of the United Nations. John Kemeny, who even then was most persuasive. Who else could have gotten a chapter of the DAR to endorse enthusiastically a petition in favor of world government?

I didn't go back for my sophomore year at Smith. We were married that November 1950. I will be 50 at the end of 198, I was married five years after the end of World War II (still the War to me). The apathetic fifties were beginning. Adjusting, understanding the ensuing social and sexual upheavals has not come easily. I was pregnant with our first child the year the word "virgin" was first used in a film and we thought, How daring! I am several years older than Gloria Steinem; yet I feel younger, or at least less streetwise. At 35, and approaching what was then considered middle age, I read The Feminine Mystique and said, "By God — Friedan's right. I haven't really thought about these things before." But the early polemics of the women's movement turned me off because I equated the movement with a diatribe against men. Every feminist I knew was reacting to an unhappy relationship with a man. Man was the enemy, and only sisters who agreed could be true revolutionaries or true women.

However, as the movement took hold and the rage subsided into coherent action, I was forced to re-examine my own ingrained attitudes and my generation's willingness not to rock the boat. A new freedom was being offered — no, thrust upon — women, and how would I cope with it?

IN 1953, John was wooed by Dartmouth and accepted an appointment as a full professor, age 27, to revitalize the College's Mathematics Department. It was a challenge for him; it was coming home for me. New Jersey could never hope to be New England.

I was ecstatic when I saw my new house — a duplex. "It has doors and stairs!" In early September 1954, we moved in and Jennifer was born three weeks later; Robert arrived 51 weeks after that.

Those two children soon acted like twins and were active enough to be quadruplets. (I have no infant furniture to hand down. It was demolished.) There were no daytime babysitters. There were no day-care centers. I was tied down and tired. I ached for the time both would be in nursery school at the same time and I could have two and a half hours of freedom! But there, separated only by air into two age groups, the children conversed constantly across the room. Robbie: "Jenny, come tie my shoes!" During those hours, Jenny became the mother, and this was not the nursery school's policy. It was considered bad for the children. How about their mother? But the school was adamant: One must go in the morning, the other in the afternoon. So I prayed for kindergarten and first grade.

Later we built a contemporary house two miles from campus. I settled into a secure, sheltered life as the wife of a tenured professor.

But I was vaguely dissatisfied. I did all those volunteer civic things one was supposed to do — boring. I also sang in a madrigal group, took lessons in oil painting, did a couple of musicals with the Dartmouth Players, and became heavily involved in state politics — all fun and worthwhile part-time activities which had a beginning and an end. I had no marketable skills; I was trained for nothing; yet I wanted something which I couldn't articulate.

John was becoming restless, too. In record time he had accomplished much of what he had set out to do in the Mathematics Department — building it into the finest undergraduate teaching department in the country. He had written a dozen books in mathematics and philosophy. He had established a computer center, the first time-sharing system in the world, and coauthored BASIC, a computer language used internationally. He was ready for a position in which he could decide educational policy.

Offers began to trickle in. Then he was deluged: a deanship of a graduate school, provostships and academic vice presidencies, and in 1969, three offers of presidencies — one from an enormous metropolitan university.

Dartmouth's President John Dickey had announced his retirement the year before, having served 23 years. A search committee was formed with input from all segments of the College.

As each outside offer came in, he turned it down, secretly hoping the impossible would happen at Dartmouth. But I knew he would seriously consider and probably accept a position elsewhere soon.

I dreaded that time. I had the power to keep him at Dartmouth. He would not leave if I asked him to stay. Hanover was home, security blanket, my nest. I wanted no change of scene, I needed the change of seasons. No desert, California, or the South. And no city! But if I held him back we'd both become desperately unhappy.

The search committee interviewed other college presidents throughout the country to find out the qualities they felt were necessary in a new president. From hundreds of candidates they interviewed dozens. The search took more than a year. President Dickey was champing at the bit.

Late in the fall of 1969 we heard a rumor that John was on the list of finalists, but no trustee had interviewed him!

The weekend of December 12 was decisive. On Friday, John gave a report to the Dartmouth Alumni Council on behalf of the committee on coeducation. On Saturday afternoon, he was asked by the trustee search committee "to give them his ideas on education." That evening Dartmouth celebrated its Bicentennial with a birthday party, Charter Day, for thousands in the field house. Walking in, I bumped into Lloyd Brace, a tall, courtly man who was chairman of the Board of Trustees. He said, "We had a very interesting discussion with your husband this afternoon."

But we knew it was too late. The Charter Day celebration was the ideal time to announce the new choice. Massive pictures of the twelve Dartmouth presidents were hung from the ceiling. And there was a place for one other. It seemed so obvious that, at an appropriate moment during the evening, a picture of the president-elect would fill that empty space. But there was no fanfare, no announcement, no picture.

Two weeks later, just before Christmas, the phone rang. I answered it and shook. I knew that voice — the chairman of the board! Could John meet with him in Hanover after Christmas to discuss some matters of importance? We just might find the time, but how about Boston, since we had already planned a brief vacation there, and Mr. Brace lived in the area? They settled on a date and a time at the Ritz- Carlton. Superstitiously, I insisted on going down by bus. Let someone else drive.

We splurged, and for the first time had a room overlooking the Boston Common. Mr. Brace arrived, we exchanged a few polite words and then, as an excuse to leave graciously, I murmured that I had some shopping to do. Shopping! I went down to the second floor of the Ritz, the tearoom, and ordered several sherries, one after the other, whiling away the eons playing with a wooden puzzle Jenny had given me for luck and finishing the New York Times crossword in record time. Was I sharp! And just a bit loaded. Sherry is not called "Sneaky Pete" irresponsibly.

At last, the elevator opened, my husband bounded out, and from across the room flashed a V. He had been offered the presidency of Dartmouth!

ABIGAIL ADAMS wrote to her husband " ... Remember the ladies. ..." Two hundred years later we are remembered, if at all, only as an afterthought.

Take, for example, two presidential searches at private-institutions:

The first search committee was small, a few trustees and faculty members. Every possible qualification of each candidate was evaluated except whether he had a wife. The wife's abilities, if any, were ignored. Her presence was never mentioned. She literally did not exist. Since several of the trustees were themselves heads of very large corporations, which still evaluate potential executives' wives, this omission was odd. Perhaps they didn't realize that the wife of a university president frequently works harder and contributes more to the institution than most wives of corporate executives. Later, in documenting the search, it was agreed that future searches must evaluate the candidate's wife. Progress.

At the other institution, the committee was enormous. Made up of trustees faculty, administrators, alumni, anD students, the diverse group bickered constantly and spent endless hours interviewing hundreds of candidates. One criterion they all agreed on was the necessity of having a visible president's wife. They did not spell out her role, but she was to be involved. The wife of one of the finalists was a practicing psychiatrist, bright and able. Her career may have knocked her husband out of the race.

In the first search all wives suffered from benign neglect. In the second, they were examined carefully. Yet both committees expected the same devotion to duty once the wife became a first lady.

The "support role" has been a tradition. Wives of public figures, wives of college presidents, have been expected to be an uncrumbling, uncomplaining column of strength. But that "support role" has expanded into one of increasing personal responsibility, and love has become a many-pillared thing.

As life has become more complex, so has the job of the university president. He has to deal with an almost infinite number of problems that didn't exist a generation ago. And each year the problems multiply.

So each year the wife's role expands. She not only has to take on her husband's personal problems and the problems of the institution, but she also is expected to be a walking encyclopedia of information about the college. If she is willing, she will be given more and more responsibility until she becomes a partner in every sense.

Dartmouth is still fairly small, but it has the complexity of a large university. And few other presidents of such complex institutions are required to preserve a tradition of accessibility. At Dartmouth there has always been a closeness between the president, his wife, and their constituents.

We live on campus. Our neighbors are the fraternities. We are not protected. Our phone number is in the book. We have no gates or guards.

We must find the time to meet with faculty, students, townspeople, and alumni. Meetings with members of the faculty are not left to deans or subordinates; talking to students is more important than a prestigious junket to Africa; good relations between town and gown are a 200-year-old tradition. We give numerous parties to which we invite a mixed group from the College: administrators, staff, Medical School, new, tenured, and retired faculty; and from the town: merchants, the chief of police, priests, and politicians. I travel with John on College business, getting to know alumni, more than any other president's wife. At receptions we split up; he takes one side of the room, I take the other, and the same sticky questions are thrown at each of us. He trusts my answers — and my judgment.

THE commitment a president's wife gives to her job is as varied as the pattern of a crazy-quilt. A few women withdraw completely, hating the responsibility, even fearing it; others have full- time outside careers and accept no institutional demands. Some play at the job, doing as little as possible. And there are those who love what I term the "housekeeping part" — planning and hostessing — but despise public appearances. All of us are propelled like baggage on a conveyor belt, but once we reach the end, there are some of us who have tried to make the most of it, maybe even a success.

What of the presidents' wives who have full-time outside careers? I know several and the number is growing. One has a job in Washington and only appears on campus during the weekend; another is a pediatrician; a third does research and made her husband promise that her career came first, before he accepted the presidency. She does nothing as first lady — adamantly.

The choice can be difficult and raise massive conflicts. Sacrifice the career, or let the husband down?

Is it fair to ask a woman, because she is a wife, to give up a profession for which she has trained for years and devote much of her time to a quite different, many- faceted job as first lady? In the sciences, particularly, this can be disastrous. With the explosion of knowledge, a few years away from the field will make her hopelessly obsolete.

Some don't feel guilty. They can say to their husbands: "Sorry, Dear, I'm doing my thing and I'm busy." And they can say to the institution: "You didn't hire me. You hired my husband." These women may feel fulfilled and liberated, but what about their husbands?

A president's wife is under great pressure to be "liberated." There are numerous articles stressing that no wife should have to fill a role if she doesn't feel comfortable in it, that society shouldn't force her to, that her life, her career, her choice . are paramount. Feminists poohpooh her choice, stressing the subservience of the job. They do not understand the unique nature of a college presidency. It is an all-consuming job. A partnership is needed to make it tolerable.

WHEN an alumnus says to us, "You're a great team!" I know that a barrier has been broken. I'm not thought of merely as a quiet wife hostessing intimate little dinners or mammoth receptions. I'm seen as a representative of Dartmouth, as a person with a mind and opinions.

"Partners," "best of friends," "a team." All these phrases are true for us, but they have been overused, made trite, and been bastardized by phonies.

A U.S. presidential aspirant and his wife were interviewed on TV several years ago. The couple sat cozily together on a couch, looking lovingly at each other as they answered the lead-in, mundane questions. In oozing cliches the husband spoke of their life as a "team effort." But as soon as the nitty-gritty questions began, the wife was patted fondly on the fanny and left the room (for the bedroom or the kitchen?). Politics, the main thrust of her husband's life, his all-consuming passion, was not included in that partnership.

Dartmouth needs two people, full time, at the top. Neither of us could do the job without the other. And that means having to give up some precious, private creative time to be with each other during lonesome, exciting, depressing, and extremely dull occasions.

Sometimes I travel with John even when I'm not scheduled for any appearances, just to keep him company to be someone to talk to at night.

He bolsters me when I need some ego; he only tells me to shut up when I have overgeneralized and interrupted for an hour. But then, I always question his accuracy in arithmetic.

"Behind every great man is a woman." In our case I have to say that "the man is behind the woman who is behind the man."

An impulse, symbolizing this partnership, became a tradition. At his first College Convocation John grasped my hand and. together we led out the academic procession. A simple tradition, but a strong statement.

FOLLOWING the inauguration of an Ivy League college president, a reception was held to honor the new* president and his wife. They stood for hours, shaking hands and chatting politely to a horde of invited guests. Suddenly an alumnus strode up to the couple, slung his arms around each, and crowed to the crowd: "Two for the price of one!"

I heard that anecdote during a conversation with several Ivy League presidents' wives at Yale's Westchester County retreat. While our husbands were in conference in the room next door, immersed in their ever-continuing debate on Ivy athletics, we raised newer issues. That anecdote was true for all of us. We were frustrated at being taken for granted by much of society, doing a multiplicity of tasks for free, because we were wives. What about pay for a president's wife? We agreed that the idea had merit. As one woman put it, "With our expertise and know-how we could receive a damn good salary on the open market."

No matter how much I do, how much I contribute, John's paycheck is no higher. The salary that comes in is for his services only. Boards of trustees make sure that a president's compensation compares fairly to that offered at other institutions — down to the smallest fringe benefit. The one factor they ignore in that comparison is the contribution (or lack of contribution) made by the wife.

The cook, the cleaning women, the yard crew, the houseman get paid for keeping up the president's house. I'm the supervisor of that staff, but I don't get a cent.

If my husband were single — a bachelor, divorced, or a widower — he would receive the same salary with the same fringe benefits, and the College would have to hire a part-time hostess, fund-raiser, spokesman, and housekeeper. John's reaction: "Never mind the housekeeper. I couldn't do the job without you." Is indispensibility worth more than compensation?

I'm not advocating a separate salary for the President's wife. I am advocating recognition in the president's paycheck for services well done by his wife.

Do I have more clout because I am unofficial, unpaid? Would being an employee of the College disenfranchise me, stifle me with rules? Does the fact that I am fighting for a cause (Dartmouth) or fund-raising for a five-year campaign voluntarily, without compensation, make me more credible? Does my active and public support of my husband give me greater effectiveness as a spokesman with the alumni? I don't know.

A letter from a sympathetic trustee wife:

... I have thought a lot about the bargain Dartmouth has in you, and I'm not sure anything can be done about that bargain condition. The next president's wife may be completely unable to function as you do, and how can that become a budget figure? The cold hard fact is that the satisfaction of being a tremendous help to John, of being enormously gifted as a hostess and enjoying a variety of interesting personalities, is going to be your only reward. Seems unfair, but very little in life is fair! ...

What official recognition would I like? I would like to be made an officer of the College, but that's not crucial. I think I should be listed in the College directory. What title? Maybe just "President's Wife." And I desperately want a College ID card!

For a fee, the College issues parking permits. John sent in the payment and, after a suitable delay, the stickers arrived. I was issued #1. John only got #2— but then he tries harder.

I do get unofficial recognition — a lot of it, public and private. I save my fan mail.

From two. student letters: " ... The chance to speak to the two of you personally was something I shall always remember. I often wonder how many other institutions of higher learning have presidents and presidential wives as eager as the two of you, who acquaint themselves with the students. I am certain that you have heard all this before, but Dartmouth is lucky to have the two of you around. ..." And from another: "You're such a refreshing person! Thank God for wonderful, 'normal' people like you! And imagine that — a president's wife! ..." From an alumnus: "... So many Dartmouth people feel that they own a piece of you both, I often wonder how you maintain your peace of mind. ..." And in public, from the chairman of the Board of Trustees, David McLaughlin, at several huge Dartmouth dinners around the country: "... I'd like to stop here just for a moment to introduce the first lady of Dartmouth, a person to whom the trustees — and I think all of us — owe a deep debt of gratitude.

And from my husband: In front of 600 people he said "... You don't know how many times she has made me look good .... " Publicly and privately he is my greatest advocate.

THE seating arrangement at almost every banquet includes a head table resting on a dais. I have sat at such somewhere between 100 and 200 times. The possible number appalls me, so I have ceased counting.

Before being seated I invariably check two items: The length of the tablecloth: Is it long enough in front to cover feet behind? The dais: do the wooden supports have any uneven boards?

There is only one advantage in being seated high above the throng. Being "honored guests," you are served first.

The disadvantages of being up there facing the crowd are numerous. If you eat first, every bite is monitored by the hungry group below. In fact, every lapse, every goof is monitored the entire evening.

Long, bell-shaped sleeves should not be worn. I cannot converse and hold my hands still; in fact, if I had no arms, I could not speak. Any sweeping gesture to emphasize a point will include a sweeping sleeve — upending a wine glass or picking up morsels of food to distribute them indiscriminately. Perhaps long sleeves should not be worn at all. Once I discovered a rapidly melting glob of orange sherbert on the elbow of a cream-colored dress. Dabbing at it only enlarged the bright orange area. Quick thinking saved the dress and delighted the Goops. (For the uneducated, The Goops is a classic tale of manners for children, about nasty little things who had no manners.) I plunged my entire elbow in my water glass and diluted the sherbert.

The length of the tablecloth is very important. It must reach below the table to hide the fact that I have taken off my shoes. I do not take off my shoes if: 1) There is only a short space between me and the edge of the dais, for then there is a real and present danger that one or both shoes will drop off and be unreachable. 2) It has been a long day. Once my feet are liberated from shoes they will swell and swell, and there will be no way to squeeze them back in.

After dinner and conversation there are the speeches. Sometimes there are several of them. The response will be either polite applause or a standing ovation. Standing ovations are more numerous than one would imagine, and preparations must be made to rise in a split second. Such preparations should include: 1) Placing your napkin on the table. If it is kept in your lap, either it will fall to the floor when you rise, or, if you grab to prevent its falling, you will end up clapping a napkin, not your hands. 2) Make sure your shoes are on. Groping to find them is most awkward, particularly when one has disappeared. 3) Beware of crossing your legs under the table. This can be dangerous. Frequently one leg will go to sleep, and leaning on the table to keep your balance makes applauding impossible. 4) If the planking is uneven, it will be your chair whose leg will be caught in the gap as you abruptly push it out to stand. This will involve frantic maneuvers to keep from sliding off the tilted seat, and, at the same time, desperate tuggings to lift the bloody chair leg from the vise that holds it.

Success! The chair moves backwards ever so smoothly. Graciously you rise, applauding — quite alone.

JUNE 1978: Another reunion banquet. Another dais. A 25th reunion banquet. (These always run on and on — three or four hours of speeches, camaraderie, awards, speeches, reminiscences, jokes, slide-shows, singing, and speeches.) My ninth 25th reunion banquet. Nine times four equals 36 hours of 25ths!

This year's banquet promises to be very long. A distinguished class, an exuberant one — the class of 1953. Rightly exuberant. They have just raised one million and 53 dollars for the College — by far the highest total any class has ever pledged to Dartmouth. They plan to celebrate. With no forewarning, I will add to the length of the evening.

It is late, my shoulders ache. (Good posture before half a thousand people becomes a pain after three hours.) I am only half listening as the president.of the class rises to extoll someone else. Background, accomplishments, personal things. The phrases wash over me. Then I begin to listen, understand, and burst into tears as the president reads a resolution from the class of 1953:

WHEREAS Jean Alexander Kemeny has rendered great service to all the classes of Dartmouth College ...

WHEREAS Jean Alexander Kemeny's service as Dartmouth's first lady has brought unique distinction to herself, our College, and her marriage ...

NOW THEREFORE, the class of 1953 of Dartmouth College does ... hereby adopt Jean Alexander Kemeny as a member of the class ... and does further declare that [she] shall henceforth be a member of the class of 1953 for life ... to receive and enjoy all the rights, privileges and benefits of membership in the world-wide fellowship of Dartmouth alumni.

June 17, 1978.

The class of 1953, 684 men and — now one woman.

But what will the older classes think? In polls they had been less than enthusiastic about admitting women to Dartmouth. Several months later I am in northern Vermont to give a short talk to a group of Rotarians. Dartmouth alumni in the area have also been invited. There is the suggestion that the Dartmouth guests stand, introduce themselves, and give their class. Six or seven rise. Then a query from one alumnus, class of 1929: "And isn't there a representative from the class of '53 here?" A long pause as we scan the room. Have I missed someone? And then it hits. Me! I bounce up to stand with the others.

True acceptance.

The new - and only - woman in the class gets a warm welcome at 1953's reunion banquet.

Printed by permission of The Stephen Greene Press from It's Different at Dartmouth by Jean Alexander Kemeny. Copyright © 1979 Jean Alexander Kemeny.

Excerpts from It's Different at Dartmouth by Jean AlexanderKemeny. The 199-page memoir ofa decade as Dartmouth's "FirstLady" will be published later thismonth by The Stephen GreenePress.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Trustees: 15 men and a woman with ultimate authority

October 1979 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureSummer Rep

October 1979 By Nancy Wasserman -

Article

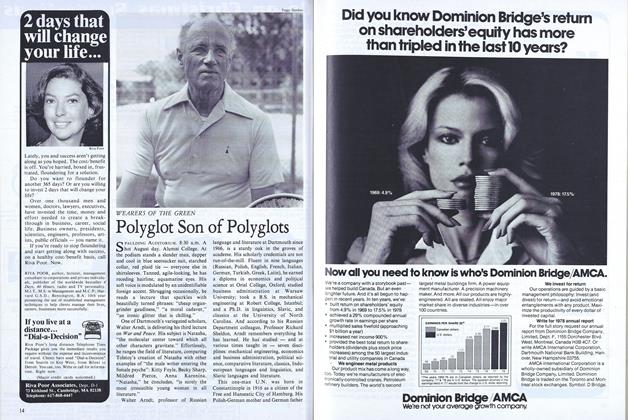

ArticleOffice of Development 1979 Report of Voluntary Giving

October 1979 -

Article

ArticlePolyglot Son of Polyglots

October 1979 By NARDI REEDER CAMPION -

Class Notes

Class Notes1978

October 1979 By JEFF IMMELT -

Article

ArticleNumismatist

October 1979 By M.B.R.

Features

-

Feature

FeatureAn Introvert at Dartmouth

April 1954 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryYoung P. Dawkins III '72

March 1993 -

Feature

FeatureFree Ride

Jan/Feb 2010 By ED GRAY ’67 -

COVER STORY

COVER STORYWhat’s Going On Here?

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2014 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

FeatureAmerica's First Hostage Negotiator

DECEMBER 1981 By Peter Bridges -

Feature

FeatureThe Next Bus Home

September 1993 By Regina Barreca '79