By Frederick W.Sternfeld. New York: New York Public Library, 1954. 176 pp. $3.00.

Professor Sternfeld has an admirable penchant for bridging what might, for less versatile hands, be disparate fields. I think particularly of his studies on Shakespeare and music, on music and the films, and, as here, on Goethe and music. He has consistently demonstrated that dual competence is not reduced competence, and surely never more clearly than in this book.

The scholarship on which Goethe and Music rests is highly detailed and intensive and the avenue of publication is similarly specialized, which implies that the "general reader" is not likely to get into this book. That is a shame. He will miss a great deal.

The observation which underlies the study is that a poet may create by "parody." Parody, as a musicologist's term, means "creating new texts to older tunes and rhythms, without any implication of irony." This very legitimate and fruitful form of poetic inspiration - for such it obviously is — was common in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, a time which absorbed all the inspiration it could get wherever it could get it and was not sensitive about copyright. Goethe, the greatest of German writers, was vastly and successfully addicted to parody.

In no less than 238 separate examples, large and small, Professor Sternfeld proves his point. An example of the parody itself and of the fascinating material in this book is the story of the tune we know best in the guise of "My Country, 'Tis- of Thee." We are all aware that the Rev. Samuel Smith s words are a parody inspired by the words and tune of "God Save the King." But in the first public performance of the British anthem in 1745 both tune and text were parodies already, and their history was so intricate that it turns out "the Hanoverians were praying for the safety of their king against the Jacobite menace to the tune of a Jacobite song." There are French revolutionary parodies "extolling the guillotine" and British counter-parodies. Goethe wrote his own parody in 1806 for the birthday of the Duchess of Weimar, and according to him "the generally known melody" (accompanied by a corps of trumpeters) "completely achieved its elevating effect for the occasion."

The famous Easter song in Faust, "Christ ist erstanden," one of Goethe's most remarkable texts, is a parody of the ancient and traditional German Easter song with the identical first line, but it also carries overtones, in its rhythmical structure, of a Latin hymn of the Renaissance, "Tandem audite me." One who admires Goethe's lyrics will find many of them treated here, in a light which he probably never imagined.

An astonishing amount of scholarly labor went into the annotations, comments, and bibliography of Goethe and Music. The introduction has some excellent remarks on the direction of Goethe's own musical tastes and clears up the old puzzle of Goethe's preference for older composers like Mozart or Bach, or for lesser contemporaries like Reichardt, rather than the "giants" of his own time, Beethoven and Schubert. This is a scholarly book, but it is also, for anyone interested in either of its two wide fields, an absorbing one.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureAn Experiment in Dormitory Living

April 1955 By JOSEPH FRANKLIN MARSH '47, -

Feature

FeatureThe 1955 Hanover Holiday Program

April 1955 By HERBERT W. HILL -

Feature

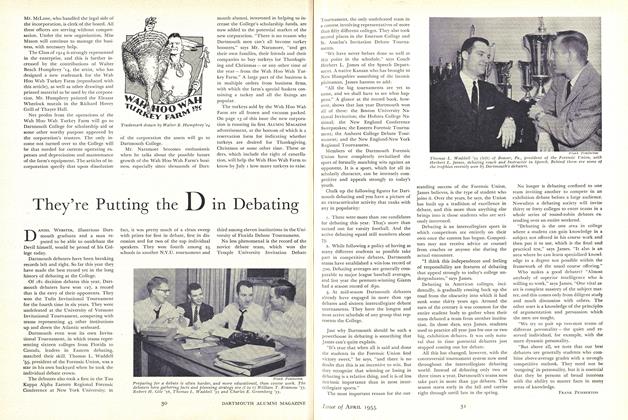

FeatureThey're Putting the D in Debating

April 1955 By FRANK PEMBERTON -

Feature

FeatureTurkeys for Dartmouth

April 1955 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

April 1955 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

April 1955 By G. H. CASSELS-SMITH '55

Books

-

Books

BooksALUMNI PUBLICATIONS

February 1921 -

Books

BooksAlumni Publications

November, 1930 -

Books

BooksLABYRINTH OF SILENCE.

OCTOBER 1970 By John Hurd ’21 -

Books

BooksPATRIOTISM AND NATIONALISM — THEIR PSYCHOLOGICAL FOUNDATIONS.

APRIL 1965 By LLOYD H. STRICKLAND -

Books

BooksCOMMUNICATING WITH EMPLOYEES.

NOVEMBER 1963 By ROBERT H. GUEST -

Books

BooksThe City Manager.

FEBRUARY, 1928 By W. A. R.